Udayagiri Caves

| Udayagiri Caves | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism, Jainism |

| District | Vidisha district |

| Deity | Varaha, Vishnu, Parshvanatha, others |

| Location | |

| Location | Udayagiri, Vidisha |

| State | Madhya Pradesh |

| Country | India |

| Geographic coordinates | 23°32′11.0″N 77°46′20″E / 23.536389°N 77.77222°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gupta era |

| Completed | c. 250-410 CE[citation needed] |

The Udayagiri Caves are twenty rock-cut caves near Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh primarily denoted to the Hindu gods Vishnu and Shiva from the early years of the 3rd century CE to 5th century CE.[1][2] They contain some of the oldest surviving Hindu temples and iconography in India.[1][3][4] They are the only site that can be verifiably associated with a Gupta period monarch from its inscriptions.[5] One of India's most important archaeological sites, the Udayagiri hills and its caves are protected monuments managed by the Archaeological Survey of India.

Udayagiri caves contain iconography of Hinduism and Jainism.[6][5] They are notable for the ancient monumental relief sculpture of Vishnu in his incarnation as the man-boar Varaha, rescuing the earth symbolically represented by Bhudevi clinging to the boar's tusk as described in Hindu mythology.[3] The site has important inscriptions of the Gupta dynasty belonging to the reigns of Chandragupta II (c. 375-415) and Kumaragupta I (c. 415-55).[7] In addition to these, Udayagiri has a series of rock-shelters and petroglyphs, ruined buildings, inscriptions, water systems, fortifications and habitation mounds, all of which remain a subject of continuing archaeological studies. The Udayagiri Caves complex consists of twenty caves, of which one is dedicated to Jainism and all others to Hinduism.[4] The Jain cave is notable for one of the oldest known Jaina inscriptions from 425 CE, while the Hindu caves feature inscriptions from 401 CE.[8]

There are a number of places in India with the same name, the most notable being the mountain called Udayagiri at Rajgir in Bihar and the Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves in Odisha.[6]

Etymology

[edit]

Udayagiri, means the 'sunrise mountain'.[11] The region of Udayagiri and Vidisha was a Buddhist and Bhagavata site by the 2nd century BCE as evidenced by the stupas of Sanchi and the Heliodorus pillar. While the Heliodorus pillar has been preserved, others have survived in ruins. Buddhism was prominent in Sanchi, near Udayagiri, in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE. According to Dass and Willis, recent archaeological evidence such as the Udayagiri Lion Capital suggests that there was a Sun Temple at Udayagiri. The Surya tradition in Udayagiri dates at least from the 2nd century BCE, and possibly one that predated the arrival of Buddhism. It is this tradition that gives it the 'sunrise mountain' name.[2]

The town is referred to as Udaygiri or Udaigiri in some texts.[6] The site is also referred to as Visnupadagiri, as in inscriptions at the site. The term means the hill at 'the feet of Vishnu'.[12][13][note 2]

Location

[edit]

Udayagiri Caves are set in two low hills near Betwa River, on the banks of its tributary Bes River.[2] This is an isolated ridge about 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) long, running from southeast to northwest, rising to about 350 feet (110 m) height. The hill is rocky and consists of horizontal layers of white sandstone, a material common in the region.[15] They are about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) west of the town of Vidisha, about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) northeast of the Buddhist site of Sanchi, and 60 kilometres (37 mi) northeast of Bhopal.[16] The site is connected to the capital Bhopal by a highway. Bhopal is the nearest major railway station and airport with regular services.

Udayagiri is slightly north of the current Tropic of Cancer, but over a millennium ago it would have been nearer and directly on it. Udayagiri residents must have seen the sun directly overhead on the Summer solstice day, and this likely played a role in the sacred of this site for the Hindus.[2][17][note 3]

History

[edit]The site at Udayagiri Caves was the patronage of Chandragupta II, who is widely accepted by scholars to have ruled the Gupta Empire in central India between c. 380-414 CE. The Udayagiri Caves were created in final decades of the 4th-century, and consecrated in 401 CE.[18] This is based on three inscriptions:[8][19][20]

- A post-consecration Sanskrit inscription in Cave 6 by a Vaishnava minister, the inscription mentions Chandragupta II and "year 82" (old Indian Gupta calendar, c. 401 CE). This is sometimes referred to as the "inscription in Chandragupta cave" or the "Chandragupta inscription of Udayagiri".

- A Shaiva devotee's Sanskrit inscription on the back wall of Cave 7, which does not mention a date but the information therein suggests it too is from 5th-century.

- A Sanskrit inscription in Cave 20 by a Jainism devotee dated 425 CE. This is sometimes referred to as the "Kumaragupta inscription of Udayagiri".

These inscriptions are not isolated. There are a number of additional stone inscriptions elsewhere at the Udayagiri site and nearby which mention court officials and Chandragupta II. Further the site also contains inscriptions from later centuries providing a firm floruit for historical events, religious beliefs and the development of Indian script. For example, a Sanskrit inscription found on the left pillar at the entrance of Cave 19 states a date of Vikrama 1093 (c. 1037 CE), mentions the word Visnupada, states that this temple that was made by Chandragupta,[note 4] and its script is Nagari both for alphabet and numerals.[22] Many of the early inscriptions in this region is in Sankha Lipi, yet to be deciphered in a way that a majority of scholars would accept it.[23]

Archaeological excavations of the 20th century on mounds between Vidisha rampart and Udayagiri have yielded evidence that suggests that Udayagiri and Vidisha formed a contiguous human settlement zone in the ancient times. Udayagiri hills would have been the suburb of Vidisha located near the confluence of two rivers[23] The Udayagiri Caves are likely euphemistically mentioned in Kalidasa text Meghduta in section 1.25 as the "Silavesma on the Nicaih hill", or the pleasure spot of Vidisha elites on the caves filled hill.[23]

Between the 5th-century and the 12th-century, the Udayagiri site remained important to Hindu pilgrims as sacred geography. This is evidenced by a number of inscriptions in scripts that have been deciphered. Some inscriptions between the 9th and the 12th centuries, for example, mention land grants to the temple, an ancient tradition that provided resources for the maintenance and operation of significant temples. These do not mention famous kings. Some of these inscriptions mention grant from people who may have been regional chiefs, while others read like common people who cannot be traced to any text or other inscriptions in Central India. One Sanskrit inscription, for example, is a pilgrim named Damodara's record from 1179 CE who made a donation to the temple.[22][note 5]

Delhi Iron Pillar

[edit]Some historians have suggested that the iron pillar in the courtyard of Quwwat-ul-Islam at the Qutb Minar site in Delhi originally stood at Udayagiri.[24][25] The Delhi pillar is accepted by most scholars as one brought to Delhi from another distant site in India, but scholars do not agree on which site or when this relocation happened. If the Udayagiri source proposal is true, this implies that the site was targeted, artifacts damaged and removed during an invasion of the region by Delhi Sultanate armies in or about the early 13th-century, possibly those of Sultan named Iltutmish. This theory is based on multiple pieces of evidence such as the closeness of its design and style with pillars found in Udayagiri-Vidisha region, the images found on Gupta era coins (numismatics), the lack of evidence for alternate sites so far proposed, the claims in Persian made by Muslim court historians of Delhi Sultanate about the loot brought to Delhi after invasions particularly related to the pillar and Quwwat-ul-Islam, and particularly the Sanskrit inscription in Brahmi script on the Delhi Iron Pillar which mentions a Chandra's (Chandragupta II) devotion to Vishnu, and it being installed in Visnupadagiri. These proposals state that this Visnupadagiri is best interpreted as Udayagiri around 400 CE.[26][27]

Archaeological scholarship

[edit]

The Udayagiri Caves were first studied in depth and reported by Alexander Cunningham in the 1870s.[2] His site and iconography-related report appeared in Volume 10 of Tour Reports published by the Archaeological Survey of India, while the inscriptions and drawings of the Lion Capital at the site appeared in Volume 1 of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicum. His comments that Udayagiri is an exclusively Hinduism and Jainism-related site, it being close to the Buddhist site of Sanchi and the Bhagavata-related Heliodorus pillar, and his dating parts of the site to between 2nd century BCE and early 5th century CE brought it to scholarly attention.[2][6]

The early Udayagiri Caves reports appealed to the prevailing conjecture about the rise and fall of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent, the hypothesis that Buddhist art predated Hindu and Jaina arts, and that Hindus may have built their monuments by reusing Buddhist ones or on top of Buddhist ones. Cunningham presumed that the broken Lion Capital at the Udayagiri Caves may be an evidence for these, and he categorized Udayagiri as originally a Buddhist site converted into a Hindu and Jaina one by "Brahmanical prosecutors".[2][28] However, nothing in or around the cave looked Buddhist, no Buddhist inscriptions or texts supported this, and it did not explain why these "Brahmanical prosecutors" did not demolish the nearby bigger Sanchi site.[29] The working hypothesis then became that the Lion Capital platform stood on a Buddhist stupa, and that if excavations were done in and around the Udayagiri Caves hills then the evidence will emerge. Such an excavation was completed and reported by archaeologists Lake and Bhandarkar in early 1910s. No evidence was found.[2][30][31] Bhandarkar, a strong proponent of the 'Buddhist converted to Hindu' site hypothesis, went further with excavations. He, state Dass and Willis, went so far as "to ransack the platform" at the Udayagiri Caves site, in an effort "to find the stupa he was certain lay below".[2] However, after an exhaustive search, his team failed to find anything underneath the platform or nearby that was even vaguely Buddhist.[2][32]

The archaeological excavations in the 1910s in the area of the nearby Heliodorus pillar yielded unexpected results, such as the inscription of Heliodorus, which confirmed that Vāsudeva and Bhagavatism (early forms of Vaishnavism) were influential by the 2nd century BCE, and which linked the Udayagiri-Besnagar-Vidisha region politically and religiously to the ancient Indo-Greek capital of Taxila.[31]

In the 1960s, a team led by archaeologist Khare revisited a broader region, at seven mounds, which included the nearby Besnagar and Vidisha. The excavation data and results were never published, except for summaries in 1964 and 1965. No new evidence was found, but the layers excavated suggested that the site was a significant town already by 6th-century BCE, and likely a major city by the 3rd-century BCE.[31]

Michael Willis – an archaeologist and Curator of early South Asian collections at the British Museum, and other scholars revisited the site in the early 2000s. Once again no Buddhist evidence was found at the Udayagiri Caves, but more artifacts related to Hinduism and Jainism. According to Julia Shaw, the evidence collected so far has led to a "major revision" about presumptions about the Udayagiri Caves archaeological site as well as the wider archaeological landscape of this region.[31] Willis and team have proposed that, perhaps Udayagiri was a Hindu and Jaina site all along, and that the evidence collected so far suggests that the Saura tradition of Hinduism may have preceded the arrival of Buddhism in this region.[2][6][note 6]

Many of the artifacts found in the area are now located in the Gwalior Fort Archaeological Museum.[31]

Description

[edit]

The caves were produced on the northeast face of the Udayagiri hills. They generally have a square or near-square plans. Many are small, but according to Cunningham, they were likely more substantial because their front showed evidence that each had a structural mandapa on pillars in their front.[15]

The caves at Udayagiri were numbered in the nineteenth century from south to north by Alexander Cunningham, and he reported only 10 lumping some of the caves together. He called the Jain cave as number 10. Later studies identified the caves separately, and their number swelled to 20. A more detailed system was introduced before mid 20th century by the Department of Archaeology, Gwalior State, with Jain cave being number 20.[35] Due to these changes, the exact numbering sequence in early reports and later publications sometimes varies. The complex has seven caves dedicated to Shaivism related caves,[36] nine to Vaishnavism, and three to Shaktism.[37] However, a few of these caves are quite small. The significant caves include iconography of all three major traditions of Hinduism. Some of the caves have inscriptions. Caves 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 13 have the most number of sculptures. The largest is Cave 19. In addition, there are rock-cut water tanks at various locations, as well as platforms and shrine monuments on the top of the hill related to Shaivism, Vaishnavism and Shaktism. There were more of these before the excavations of 1910s, but these were destroyed in the attempt to find evidence of Buddhist monuments underneath.[38][39]

Cave 1

[edit]

Cave 1 is the southernmost cave and a false one because one of the side and its front is not of the original rock but added in. Its roof is integrated from the natural ledge of the rock. It moulding style is similar to those found in Tigawa Hindu temple. The mandapa inside the temple is a square with 7 feet (2.1 m) side, while the sanctum is 7 feet by 6 feet. Outside, Cunningham reported four square pillars. The back wall of the cave has a deity carved into the rock wall, but this was damaged by chiseling later at some point. The iconographic markers are gone and the deity is unknown.[15][40]

Cave 2

[edit]Cave 2 is to the north of Cave 1, but still on the southern foothill isolated from the main cluster of caves. Its front wall was damaged at some point, and the interior has been eroded by weather. It is about 48 square feet (4.5 m2) in area and the only traces of two pilasters are visible, along with evidence underneath its roof of a structural mandapa.[15] The doorjamb has some reliefs, but these are only partially visible.[41]

Cave 3: Shaivism

[edit]Cave 3 is the first of the central group or cluster of shrines and reliefs. It has a plain entrance and a sanctum. Traces of two pilasters are seen on both sides of the entrance and there is a deep horizontal cutting above which shows that there was some sort of portico (mandapa) in front of the shrine. Inside there is a rock-cut image of Skanda, the war god, on a monolithic plinth. The mouldings and spout of the plinth are now damaged. The Skanda sculpture is desecrated, with his staff or club and parts of limbs broken and missing. The surviving remnants show an impressive muscular torso, with Skanda's weight distributed equally on both legs.[42]

Cave 3 is sometimes called the Skanda temple.[43]

Cave 4: Shaivism and Shaktism

[edit]Cave 4 was named the Vina cave by Cunningham.[note 7] It presents both Shaiva and Shakti themes. It is an excavated temple of about 14 feet by 12 feet. The cave has a style that suggests that it was completed with the other caves.[43] The doorway frame is plain but it is surrounded by three bands of rich carvings.[15] In one of these bands, in a circular boss to the left of the door is depicted a man playing the lute, while another boss to the right shows another man playing the guitar. River goddesses Ganga and Yamuna flank the doorway on two short pilasters with bell capitals.[15]

The temple sanctum is dedicated to Shiva, with the sanctum containing an ekamukha linga, or a linga with a face carved on it. Outside its entrance, in what was a mandapa and now is eroded remnants of a courtyard are matrikas (mother goddesses), eroded likely because of weathering. This is one of the three groups of matrikas found at Udayagiri site in different caves. The prominent presence of the matrikas in a cave dedicated to Shiva suggests that the divine mothers had been accepted within the Shaivism tradition by about 401 CE.[43] Some scholars speculate that there may have been Skanda here, but others state the evidence is unclear.[43]

The cave is also notable for depicting a harp player on its lintel, putting a floruit of 401 CE for this musical instrument in India.[44]

Cave 5: Vaishnavism

[edit]Cave 5 is a shallow niche more than a cave and contains the much-celebrated colossal Varaha panel of Udayagiri Caves. It is the narrative of Vishnu in his Varaha or man-boar avatar rescuing goddess earth in crisis.[45] Willis has described the relief as the "iconographic centre-piece of Udayagiri".[46]

The Hindu legend has roots in the Vedic literature such as Taittariya Samhita and Shatapatha Brahmana, and is found in many post-Vedic texts.[47][note 8] The legend depicts goddess earth (Bhudevi, Prithivi) in an existential crisis after she has been attacked and kidnapped by oppressive demon Hiranyaksha, where neither she nor the life she supports can survive. She is drowning and overwhelmed in the cosmic ocean. Vishnu emerges in the form of a man-boar avatar.[49][50] He, as the hero in the legend, descends into the ocean, finds her, she hangs onto his tusk, he lifts her out to safety. The good wins, the crisis ends, and Vishnu once again fulfills his cosmic duty. The Varaha legend has been one of many historic legends in the Hindu text embedded with right versus wrong, good versus evil symbolism, and of someone willing to go to the depths and do what is necessary to rescue the good, the right, the dharma.[47][45][51] The Varaha panel narrates this legend. The goddess earth is personified as the dangling woman, the hero as the colossal giant. His success is cheered by a galaxy of the divine as well as human characters valued and revered in the 4th-century. Their iconography of individual characters is found in Hindu texts.[45][51]

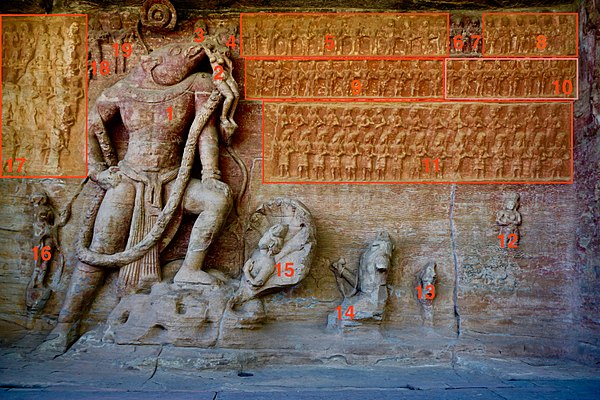

The panel shows (the number corresponds to the attached image):[45]

- Vishnu as Varaha

- Goddess earth as Prithivi

- Brahma (sitting on lotus)

- Shiva (sitting on Nandi)

- Adityas (all have solar halos)

- Agni (hair on fire)

- Vayu (hair airy, puffed up)

- Eight Vasus (with 6&7, Vishnu Purana)

- Eleven Rudras (ithyphalic, third eye)

- Ganadevatas

- Rishis (Vedic sages, wearing barks of trees, a beard, carrying water pot and rosary for meditation)

- Samudra (Ocean)

- Gupta Empire minister Virasena

- Gupta Empire king Chandragupta II

- Nagadeva

- Lakshmi

- More Hindu sages (incomplete photo; these include the Vedic Saptarishis)

- Sage Narada playing Mahathi (Tambura)

- Sage Tumburu playing Veena[note 9]

The characters are dressed in traditional dress. The gods wear dhoti, while the goddess is in a sari, in the Varaha panel.[45]

Cave 6: Shaktism, Shaivism, Vaishnavism

[edit]Cave 6 is directly beside Cave 5 and consists of rock-cut sanctum entered through an elaborate T-shaped door.

The sanctum door is flanked by guardians. Beside them, on either side, are figures of Vishnu and of Shiva Gangadhara. The cave also has Durga slaying Mahishasura – the deceptive shape-shifting buffalo demon. This is one of the earliest representations of this Durga legend in a cave temple.[52][note 10] Of special note also is the figure of seated Ganesha in this cave, to the left of the entrance, and the rectangular niche with seated goddesses, located to the right. The Ganesha is potbellied, has modaka (laddu or rice balls, sweetmeat) in his left hand and his trunk is reaching out to get one.[54][note 11] This makes the cave notable as it sets the floruit for the widespread acceptance and significance of Ganesha in the Hindu pantheon to about 401 CE. The presence of all three major traditions within the same temple is also significant and it presages the norm for temple space in subsequent centuries.[55]

In addition to Durga, Cave 6 depicts the Hindu matrikas (mother goddesses from all three traditions). One group of these divine mothers are so "badly destroyed", states Sara L. Schastok, that only limited information can be inferred. The matrikas are prominent because they are placed immediately to the right of Visnu. The outline of the seated matrikas in Cave 6 suggests that they are similar to early Gupta era iconography for matrikas such as those found in Badoh-Pathari and Besnagar archaeological sites.[43]

Outside the cave is a panel with an inscription that mentions Gupta year 82 (401 CE), and that the Gupta king Chandragupta II and his minister Virasena visited this cave.[56] In the ceiling of the cave is an undated pilgrim record of somebody named Śivāditya.[57]

Cave 7: Shaktism

[edit]Cave 7 is located a few steps east of Cave 6. It consists of a large niche containing damaged figures of the eight mother goddesses, each with a weapon above their head, carved on the back wall of the cave. The cave is flanked by shallow niches with abraded figures of Kārttikeya and Gaṇeśa, now visible only in outline.[58][note 12]

The Passage

[edit]There is a passage prior to Cave 8 which consists of a natural cleft or canyon in the rock running approximately east to west. The passage has been subject to modifications, the sets of steps cut into the floor being the most conspicuous feature. The lowest set of steps on the right-hand side are eroded. Sankha Lipi or shell inscriptions – so-called because of their shell-like shape, are found on the upper walls of the passage. These are quite large. Those inscriptions have been cut through to make the caves, which means they existed before the caves were created around 401 CE. The inscriptions had not been deciphered, and proposed interpretations have been controversial.[60] The upper walls of the passage have large notches at several places, indicating that stone beams and slabs were used to roof over parts of the passage, giving it a significantly different appearance from what can be seen today.

Cave 8

[edit]Cave 8 was named the "Tawa Cave" by Cunningham, after its crown that looks like the Indian griddle which locals use to bake their daily bread and call the baking plate as Tawa.[61] The cave is a bit to the right of the passage. It is excavated into a hemispherical dome-shaped rock and has a large nearly flat rock crown. It is about 14 feet long and 12 feet broad. The cave is badly damaged, but contains a historically significant inscription. Outside the cave, the empty hollow remnants provide the evidence that there was a mandapa outside this cave. To the sides of the entrance are eroded dvarapalas (guardian reliefs) with a bushy hairstyle found for dvarapalas in other caves. The cave is notable for its 4.5 feet (1.4 m) lotus carving on the ceiling.[61]

The famed early 5th-century Sanskrit inscription in this cave is on its back wall. It is five lines long, in a Vedic meter. Some parts of the inscription are damaged or have peeled off.[61][62] The inscription links the Gupta king Chandra Gupta II and his minister Virasena to this cave. It has been translated as follows:

The inner light which resembles the sun, which pervades the heart of the learned, but which is difficult find among men upon the earth, that is the wonder called Chandragupta, Who * * * (damaged), Of him, like a saint among great kings became the minister [...], whose name was Virasena, He was a poet, resident of Pataliputra, and knew grammar, law and logic, Having come here with his king, who is desirous of conquering the whole world, he made this cave, through his love to Sambhu.

– Cave 8 inscription; Translators: Michael Willis[63] / Alexander Cunningham[61]

The inscription does not give a date, but the inscription in Cave 6 does. The "love to Shambhu (Shiva)" is notable given the Varaha panel and royal sponsors of the Gupta era also revere Vishnu.[61]

Caves 9-11

[edit]The three caves are small excavations to the side of Cave 8. All three are next to each other. Their entrance opens north-northwest, and all have damaged Vishnu carvings. Cave 9 and 10 are rectangular niche like openings, while Cave 11 is a bit bigger and has a square plan. Cave 10, the middle one is a bit higher in its elevation.[64]

Cave 12: Vaishnavism

[edit]Cave 12 is a Vaishnavism-related cave known for its niche containing a standing figure of Narasimha or the man-lion avatar of Vishnu. The Narasimha carving is flanked below by two standing images of Vishnu.[note 13]

Cave 12 is notable for having the clearest evidence that the cave was excavated into a rock with pre-existing inscriptions. The script is Sankha lipi, probably several versions of it given the different styles, all of which remain undeciphered. It is this which confirms that Udayagiri and Vidisha were inhabited and an active site of literate people before these caves were produced. Further, it also establishes 401 CE as the floruit for the existence and the use of Sankha lipi. The cave also has a flat top with evidence that there was likely a structure above, but this structure has not survived into the modern era.[66]

Cave 13: Vaishnavism

[edit]Cave 13 contains a large Anantasayana panel, which depicts a resting figure of Vishnu as Narayana.[67] Below the leg of Vishnu are two men, one larger kneeling devotee in namaste posture, and another smaller standing figure behind him. The kneeling figure is generally interpreted as Chandragupta II, symbolising his devotion to Vishnu. The other figure is likely his minister Virasena.[68][69]

Cave 14

[edit]Cave 14, the last cave on the left hand side at the top of the passage. It consists of a recessed square chamber of which only two sides are preserved. The outline of the chamber is visible in the floor, with a water channel pierced through the wall on one side as in the other caves at the site. One side of the doorjamb is preserved, showing jambs with receding faces but without any relief carving.

Caves 15-18

[edit]

Cave 15 is small square cave without separate sanctum and pitha (pedestal).[70]

Cave 16 is a Shaivism related cave based on the pitha and iconography. The sanctum and the mukha-mandapa are both squares.[71]

Cave 17 has a square plan. To the left of its entrance is single dvarapala. Further left is a niche with Ganesha image. On the right of the entrance is a niche with Durga in her Mahishasura-mardini form. The cave has an intricate symmetric lotus set in a geometric pattern on the ceiling.[72]

Cave 18 is notable for including a four armed Ganesha. With him is a devotee who is shown carrying a banana plant.[73]

Cave 19: Shaivism

[edit]

Cave 19 is also called the "Amrita Cave". It is close the Udayagiri village. It is the largest cave in Udayagiri Caves group, being 22 feet (6.7 m) long by 19.33 feet (5.89 m) broad. It has four massive square cross-section, 8 feet (2.4 m) high pillars which support the roof. The pillars have intricately decorated capitals with four horned and winged animals standing on their hind legs, and touching their forefeet touch their mouths. The roof of the cave, states Cunningham, is divided "into nine square panels by the architraves crossing over the four pillars". The temple was likely much larger with its mandapa in front, given the structural evidence in the form of ruins.[74]

The doorway of Cave 19 is more extensively ornamented than other caves. The pilasters are of the same pattern as the pillars inside. River goddesses Ganga and Yamuna flank the doorway. Above is a long deeply carved sculpture representing the samudra manthan mythology, depicting Suras and Asuras churning the cosmic ocean. It is this narrative of this Hindu myth that led Cunningham to propose the name of the cave to be "Amrita cave".[74] There is a carving near Cave 19 that shows Parvati's family, that is Shiva, Ganesha and Kartikeya.[73] The cave has two Shiva lingas, of which one is a mukhalinga (linga with face). This cave had a Sahastralinga (main linga with many subsidiary lingas), which was moved to the ASI museum in Sanchi.[36]

Cave 19 has a Sanskrit inscription in Nagari script dated 1036 CE by a common pilgrim name Kanha, who donated resources to the temple, and the inscription expresses his devotion to Visnu.[22]

Cave 20: Jainism

[edit]

Cave 20 is the only cave in the Udayagiri Caves complex that is dedicated to Jainism. It is in the northwestern edge of the hills. At the entrance is the image of the Jain tirthankara Parshvanatha sitting under a serpent hood. The cave is divided into five rectangular rooms with stones stacked, the total length of 50 feet (15 m) that is about 16 feet (4.9 m) deep.[75] The southern room connects to another excavated section consisting of three rooms. In the northern rooms is an eight-line inscription in Sanskrit. It praises the Gupta kings, for bringing prosperity to all, then notes that a Sangkara has set up a statue of Parshva Jina in this cave after commanding a cavalry, later giving up his passions, withdrawing from the world and becoming a yati (monk).[75]

The cave has other reliefs, such as those of the Jinas. These are significant because they have chattras (umbrella-like cover) carved over them, an iconography that is found in Jain caves built centuries later in many parts of India. These are generally not found in Jain statues carved before the 4th-century.[76] The cave also includes a somewhat damaged image of Ganesha on its floor, where is depicted carrying an axe while looking in his left direction.[77]

Significance

[edit]According to Willis, Udayagiri's Hindu history long predates the 4th-century.[78] It was a center of astronomy and Hindu calendar-related activity, given its sculptures, sundials, and inscriptions. These made Udayagiri a sacred space and gave it its name that means "sunrise mountain". It was likely first modified by the king Samudragupta in mid 4th-century. His descendant Chandragupta II reworked these caves a few decades later, to revitalize the Hindu king concept to be both the paramount sovereign (cakravartin) and the supreme devotee of the god Vishnu (paramabhāgavata). This evolved the role of Udayagiri from it being the historic center for Hindu astronomy into an "astro-political node". Chandragupta II thereafter came to be titled as Vikramaditya – literally, "he who is the sun of prowess – in Indian texts, states Willis.[78][note 15] According to Patrick Olivelle – an Indologist and a professor of Sanskrit, Udayagiri was important to the Gupta Hindu kings who were "polytheistic with remarkable tolerance" in an era where the popular religion was "basically henotheistic".[80]

According to Heinrich von Stietencron - an Indologist and professor of Comparative Religion, the Udayagiri Caves narrates Hindu thought and legends with far deeper roots in the Vedic tradition.[47] These roots are found in many forms, of which Vishnu avatars are particularly well formulated. He is the god who descends to bring order and equilibrium when chaos and injustice of one or more forms thrives in the world. Some of his avatars such as Narasimha, Varaha, Vamana/Trivikrama, and Rama are templates for kings. Their respective legends are well structured for a discussion of right and wrong, justice and injustice, rights and duties, of dharma in its various dimensions. The man-boar Varaha avatar found in Udayagiri itself is a story found in various forms, starting with the Vedic text Taittiriya Samhita section VII.1, where Prajapati takes the form of boar to rescue earth first before creating gods and lifeforms that earth could support.[47] The story's popularity was well spread, as the symbolic boar saving the earth goddess is also found in the Shatapatha Brahmana XVI.1, the Taittiriya Brahmana, Taittiriya Aranyaka and others, all these Vedic era texts are estimated to have been complete by 800 BCE. The Varaha iconography has been historic symbolism of someone willing to go to the depths and do what is necessary to rescue earth and dharma, and this has had an obvious appeal and parallels to the role of king in the Hindu thought.[47] Udayagiri caves narrate this legend, but go one step further. The Varaha relief in Udayagiri does not revitalize Hindu kingship, according to Heinrich von Stietencron, rather it is a tribute to his victories that was likely added to the cave temples complex as a shallow niche between 410 and 412 CE.[47] It signifies his success and with his success, the return of dharma. It may have marked the year when Chandragupta II assumed the title of Vikramaditya.[47]

The Stietencron proposal does not explain the presence of a bowing figure in front of the Vishnu Varaha. The royally dressed man has been broadly interpreted as king Chandragupta II acknowledging dharma and duty symbolized by Vishnu Varaha as above the king.[81][82] Stietencron states that it indeed is a norm in the Hindu sculptural art tradition to not represent transitory achievements of mortal kings or any individual, rather they predominantly emphasize spiritual quest and narrate ahistoric, symbolic legends from Hindu texts. The Udayagiri Caves are significant, states Stietencron, because they are likely a political statement.[83]

According to Julia Shaw, the Udayagiri sculptures are significant because they suggest that the avatara concept was fully developed by about 400 CE.[84] The full display of iconography across multiple caves for Vishnu, Shiva and Durga suggests that Hinduism was thriving along with Buddhism in post-Mauryan era in ancient India. The Udayagiri temples represent, state Francis Ching and other scholars, the "earliest intact Hindu architecture" and display the "essential attributes of a Hindu temple" in the form of sanctum, mandapa and a basic plan.[85] According to James Harle, the Udayagiri caves are significant for being "a common denominator of the early Gupta style".[86] He states that Udayagiri temples are, along with those as Tigawa and Sanchi, probably the earliest of surviving Hindu temples.[87] The Udayagiri temples are the only that can be confidently linked to the Gupta Empire, states George Michell. While new ancient temples are being identified every year on the Indian subcontinent but their dating remains uncertain. the Udayagiri Caves can be dated and they are earliest accepted examples of surviving rock-based north Indian temple.[88]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The lion capital is significant in its design, the octagonal base the lion sits on, and the animals carved on the eight sides: a bull, an elephant, a gaur, a tiger with wings, two winged creatures, a horse and a double-humped camel. This sat on a pillar.

- ^ The term Visnupadagiri occurs in the Mahabharata, and has been variously interpreted to mean sites in Kashmir, Anga or other regions.[14]

- ^ The tropic of cancer has been shifting south on a cycle of about 41,000 years. See Circle of latitude#Movement of the Tropical and Polar circles.

- ^ Willis states that "this means there was a living oral tradition in central India for six centuries that credited the temple to Chandragupta".[22]

- ^ The Udayagiri Caves Hindu temples are mentioned in inscriptions outside its near vicinity, states Willis. Some mention the temples for context, some record donations to the temples at Udayagiri. One of the mentioned Bhailasvami temple in 10th to 12th-century inscriptions is now missing.[22]

- ^ The original theory that there may be Buddhist remains below the Udayagiri temples remains active, state Dass and Willis, and the search for "Buddhist remains is still going on".[33] One unsolved puzzle is that some of the niches at smaller Udayagiri Caves seem to be cutting through Sankha Lipi inscriptions and not produced on virgin rock. These suggest that the wall had pre-existing huge, ostentatious Sankha Lipi inscription carvings. The caves were produced by cutting through these undeciphered inscriptions and into the face of the massive rock. Scholars wonder whether these inscriptions were related to Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism or some other tradition, and whether they relate to inter-religious relations in centuries before the 4th century CE.[23][34]

- ^ Cunningham's report in 1880 numbered it Cave 3.[15]

- ^ Mitra compares the entire composition to a number of Hindu texts, including the Vishvarupa verses in Chapter 11 of the Bhagavada Gita.[48]

- ^ Some Indian iconography shows him as horse faced, but not this cave. Here the iconography for Tumburu and Narada in this panel is more consistent with the guidelines in Vaikhanasayama, a Hindu text.[45]

- ^ The surviving images of Durga within the Udayagiri Caves complex are found in five places: four times in Cave 6 alone and in Cave 17. The best surviving image of her is in the front of Cave 6. These are 10 armed Durgas, with iconography found elsewhere. The surviving images have different style, possibly because different guild traditions worked on these caves at the same time.[53]

- ^ Ganesha appears in seven places within the Udayagiri Caves complex.[54]

- ^ Harper makes novel interpretations of the goddesses-related iconography in this and other Udayagiri caves, then links it to suggests early roots of tantra in ancient India.[59] Willis disagrees and finds Harper's re-interpretation of Udayagiri Shaktism-related temples and iconography as tautological.[58]

- ^ There are many images of Vishnu in Udayagiri. Of these nine are standing images. They are found in Caves 6, 9, 10, 11 and 12.[65]

- ^ ୯ is 9 in modern Odia.

- ^ The relationship and equivalence of Surya, Vishnu and others was a theme of these cave temples.[79]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson. p. 533. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Meera Dass; Michael Willis (2002). "The lion capital and the antiquity of sun worship in central India". South Asian Studies. 18: 25–45. doi:10.1080/02666030.2002.9628605. S2CID 191353414.

- ^ a b Fred Kleiner (2012), Gardner’s Art through the Ages: A Global History, Cengage, ISBN 978-0495915423, page 434

- ^ a b Margaret Prosser Allen (1992), Ornament in Indian Architecture, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 978-0874133998, pages 128-129

- ^ a b James C. Harle (1974). Gupta sculpture: Indian sculpture of the fourth to the sixth centuries A.D.. Clarendon Press, Oxford. pp. 7–9.

- ^ a b c d e Cunningham 1880, pp. 46–53.

- ^ The inscriptions are dealt with in J. F. Fleet, Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and their Successors, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. 3 (Calcutta, 1888), hereinafter CII 3 (1888); for another version and interpretation: D. R. Bhandarkar et al, Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. 3 (revised) (New Delhi, 1981).

- ^ a b Sara L. Schastok (1985). The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India. BRILL Academic. pp. 36–37. ISBN 90-04-06941-0.

- ^ British Library Online

- ^ The Past Before Us, Romila Thapar p.361

- ^ Sita Pieris; Ellen Raven (2010). ABIA: South and Southeast Asian Art and Archaeology Index: Volume Three – South Asia. BRILL Academic. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-90-04-19148-8.

- ^ Balasubramaniam, R. (2008). "Iron Pillar at Delhi". In Helaine Selin (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Netherlands. pp. 1131–1136. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8658. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ^ M. Willis, ‘Inscriptions from Udayagiri: Locating Domains of Devotion, Patronage and Power in the Eleventh Century’, South Asian Studies 17 (2001): 41-53.

- ^ J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL Academic. pp. 202–203. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cunningham 1880, pp. 46–47.

- ^ A. Ghosh, An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, 2 vols. New Delhi, 1989: s.v. Besnagar.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 15–27, 248.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 1–3, 54, 248.

- ^ JF Fleet (1888), Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings and Their Successors, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol III, pages 25-34

- ^ Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- ^ BECKER, CATHERINE (2010). "NOT YOUR AVERAGE BOAR: THE COLOSSAL VARĀHA AT ERĀṆ, AN ICONOGRAPHIC INNOVATION". Artibus Asiae. 70 (1): 127. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 20801634.

- ^ a b c d e f Michael Willis (2001), "Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century", South Asian Studies, Volume 17, Number 1, pages 41-53

- ^ a b c d Julia Shaw (2013). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-1-61132-344-3.

- ^ M.I. Dass and R. Balasubramanium (2004), Estimation of the original erection site of the Delhi Iron Pillar at Udayagiri, Indian Journal of History of Science, Volume 39, Issue 1, pages 51-54, context: 51-74

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam, ‘Identity of Chandra and Vishnupadagiri of the Delhi Iron Pillar Inscription: Numismatic, Archaeological and Literary Evidence’, Bulletin of Metals Museum 32 (2000): 42-64; Balasubramaniam and Meera I. Dass, ‘On the Astronomical Significance of the Delhi Iron Pillar’, Current Science 86 (2004): 1135-42.

- ^ R Balasubramaniam, MI Dass and EM Raven (2004), The Original Image atop the Delhi Iron Pillar, Indian Journal of History of Science, Vol. 39, Issue 2, pages 177-203

- ^ HG Raverty (1970, Translator),Tabakat-i-Nasari: A General History of the Muhammadan Dynasties of Asia, including Hindustan from AH 194 (810 AD) to AH 658 (1260 AD) by Maulana Minhaj-ud-din Abu-uma-I-Usman, Vol. 1, Oriental, pages 620-623

- ^ Cunningham 1880, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Meera Dass; Michael Willis (2002). "The lion capital and the antiquity of sun worship in central India". South Asian Studies. 18: 31–32 with footnote 31 on page 43.

- ^ HH Lake (1910), Besnagar, Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 23, pages 135-145

- ^ a b c d e Julia Shaw (2013). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-61132-344-3.

- ^ DR Bhandarkar (1915), Excavations at Besnagar, Annual Report 1913-1914, Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India Press, pages 186-225 with plates; also the ASI Western Circle Report 1915, Excavations, pages 59-71 with plates

- ^ Meera Dass; Michael Willis (2002). "The lion capital and the antiquity of sun worship in central India". South Asian Studies. 18: 31–32 with footnote 32 on page 43.

- ^ Michael Willis (2001), "Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century", South Asian Studies, Volume 17, Number 1, pages 41-53 with note 4 on page 50

- ^ D. R. Patil, The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill (Gwalior, 1948).

- ^ a b Meera Dass 2001, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 7–8, 80–81.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 29, 251–252.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, p. 12.

- ^ J. C. Harle, Gupta Sculpture: Indian Sculpture of the Fourth to the Sixth Centuries A.D. (Oxford [England]: Clarendon Press, 1974).

- ^ a b c d e Sara L. Schastok (1985). The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India. BRILL Academic. pp. 36–41, 65–67. ISBN 90-04-06941-0.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 26, 251.

- ^ a b c d e f Debala Mitra, ’Varāha Cave at Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study’, Journal of the Asiatic Society 5 (1963): 99-103; J. C. Harle, Gupta Sculpture (Oxford, 1974): figures 8-17.

- ^ Willis 2009. p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e f g H. von Stietencron (1986). Th. P. van Baaren; A Schimmel; et al. (eds.). Approaches to Iconology. Brill Academic. pp. 16–22 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-07772-3.

- ^ Debala Mitra (1963), ’Varāha Cave at Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study’, Journal of the Asiatic Society, Vol. 5, page 103

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 154–155, 223–224. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ a b Joanna Gottfried Williams (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-0-691-10126-2.

- ^ Phyllis Granoff, ‘Mahiṣāsuramardinī: An Analysis of the Myths’, East and West 29 (1979): 139-51.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 86–88.

- ^ a b Meera Dass 2001, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Willis, The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual, p. 142.

- ^ Cunningham, Bhilsa Topes (1854): 150; Thomas, Essays (1858) 1: 246; Cunningham, ASIR 10 (1874-77): 50; Fleet, CII 3 (1888): number 6; Bhandarkar, EI 19-23 (1927-36): appendix, number 1541; Bhandarkar, Chhabra and Gai, CII 3 (1981): number 7; Goyal (1993): number 10. The most recent reading and translation is in Willis, The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009): 57 ISBN 978-0-521-51874-1.

- ^ Cunningham, ASIR 10 (1874-77): 50, plate xix, number 3; GAR (VS 1988/AD 1931-32): number 5; Dvivedī (VS 2004): number 714.

- ^ a b Willis 2009, p. 315 note 43.

- ^ Katherine Harper (2002), "The Warring Śaktis: A Paradigm for Gupta Conquests" in The Roots of Tantra, ISBN 978-0-7914-5305-6, pages 115-131

- ^ Richard Salomon, ‘New Sankalipi (Shell Character) Inscriptions’, Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik 11-12 (1986): 109-52. Claims regarding decipherment must be discounted, see Salomon, ‘A Recent Claim to Decipherment of the Shell Script’, JAOS 107 (1987): 313-15; Salomon, Indian Epigraphy (Oxford, 1998): 70

- ^ a b c d e Cunningham 1880, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 4–5, 39–41.

- ^ Willis 2009, pp. 4–5, 39–41, 200.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 88.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-61069-566-4.

- ^ Willis 2009, p. 35.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 216, 283.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 80, 286.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 288–290.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, pp. 85–86, 291–293.

- ^ a b Meera Dass 2001, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Cunningham 1880, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Cunningham 1880, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. pp. 62 with footnote 53. ISBN 978-90-04-20630-4.

- ^ Meera Dass 2001, p. 85.

- ^ a b Willis 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ R. Balasubramaniam (2005). Story of the Delhi Iron Pillar. Foundation. pp. 17–26. ISBN 978-81-7596-278-1.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ^ James C. Harle (1974). Gupta sculpture: Indian sculpture of the fourth to the sixth centuries A.D.. Clarendon Press, Oxford. pp. 10–11 with Plates 12–15.

- ^ Debala Mitra (1963), Varāha Cave at Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study, Journal of the Asiatic Society, Vol. 5, pages 99-103

- ^ H. von Stietencron (1986). Th. P. van Baaren; A Schimmel; et al. (eds.). Approaches to Iconology. Brill Academic. pp. 16–17. ISBN 90-04-07772-3.

- ^ Julia Shaw (2013). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-61132-344-3.

- ^ Francis D. K. Ching; Mark M. Jarzombek; Vikramaditya Prakash (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-118-00739-6.

- ^ James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ George Michell (1977). The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms. University of Chicago Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cunningham, Alexander (1880), Report of Tours Bundelkhand and Malwa 1874-1875 and 1876-1877, Archaeological Survey of India, Vol. 10, ASI, Government of India,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Meera Dass (2001), Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, Art, Architecture and Landscape, De Monfort University

- Asher, Frederick M. (1983). B.L. Smith (ed.). "Historical and Political Allegory in Gupta Art". Essays on Gupta Culture. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: 53–66.

- Willis, Michael (2004). The Archaeology and Politics of Time. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. pp. 33–58. ISBN 90-6980-148-5.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51874-1.