Annunciation to the shepherds

The annunciation to the shepherds is an episode in the Nativity of Jesus described in the Bible in Luke 2, in which angels tell a group of shepherds about the birth of Jesus. It is a common subject of Christian art and of Christmas carols.

Biblical narrative

[edit]

As described in verses 8–20 of the second chapter of the Gospel of Luke, shepherds were tending their flocks out in the countryside near Bethlehem, when they were terrified by the appearance of an angel. The angel explains that he has a message of good news for all people, namely that "Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger."[1]

After this, a great many more angels appear, praising God with the words "Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests."[2] Deciding to do as the angel had said, the shepherds travel to Bethlehem, and find Mary and Joseph and the infant Jesus lying in the manger, just as they had been told. The adoration of the shepherds follows.

Translational issues

[edit]

The King James Version of the Bible translates the words of the angels differently from modern versions, using the words "Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men".[3] Most Christmas carols reflect this older translation, with "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear", for example, using the words "Peace on the earth, good will to men, / From Heaven's all gracious King."

The disparity reflects a dispute about the Greek text of the New Testament involving a single letter.[4] The Greek text accepted by most modern theological scholars today[5][6] uses the words epi gēs eirēnē en anthrōpois eudokias (ἐπὶ γῆς εἰρήνη ἐν ἀνθρώποις εὐδοκίας),[7] literally "on earth peace to men of good will", with the last word being in the genitive case[6] (apparently reflecting a Semitic idiom that reads strangely in Greek[6]). Most ancient manuscripts of the Greek New Testament have this reading. The original version of the ancient Codex Sinaiticus (denoted א* by scholars[7][8]) has this reading,[5] but it has been altered by erasure of the last letter[4][9] to epi gēs eirēnē en anthrōpois eudokia (ἐπὶ γῆς εἰρήνη ἐν ἀνθρώποις εὐδοκία), literally "on earth (first subject: peace) to men (second subject: good will)," with two subjects in the nominative case.[6] Expressed in standard English, this gives the familiar "Peace on earth, good will to men" of many ancient Christmas carols.

Even though some other ancient Greek manuscripts (and many medieval ones) agree with the edited Codex Sinaiticus, most modern religious scholars and Bible translators accept the reading of the majority of ancient manuscripts,[5] translating as "on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests"[2] (NIV) or "on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased"[10] (ESV).

The Douay-Rheims Bible, translated from the Latin Vulgate, derives from the same Greek text as the original Codex Sinaiticus, but renders it "on earth peace to men of good will".[11] In the New American Bible, this is updated to "on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests".[12][13]

Theological interpretation

[edit]It is generally considered significant that this message was given to shepherds, who were located on the lower rungs of the social ladder in first-century Judea. Contrasting with the more powerful characters mentioned in the Nativity, such as the Emperor Augustus, they seem to reflect Mary's words in the Magnificat: "He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble."[14] The shepherds, taken as Jewish, also combine with the Gentile Three Magi, in later tradition thought to be one each from the three continents then known, to represent the first declaration of the Christian message to all the peoples of the world.

The phrase "peace to men on whom his favor rests" has been interpreted both as expressing a restriction to a particular group of people that God has chosen[15] and inclusively, as God displaying favor to the world.[16]

Depiction in art

[edit]

Initially depicted only as part of a broader Nativity scene, the annunciation to the shepherds became an independent subject for art in the 9th century,[18] but has remained relatively uncommon as such, except in extended cycles with many scenes. The standard Byzantine depiction, still used in Eastern Orthodox icons to the present, is to show the scene in the background of a Nativity, typically on the right, while the Three Magi approach on the left. This is also very common in the West, though the Magi are very often omitted. For example, the 1485 Adoration of the shepherds scene by Domenico Ghirlandaio includes the annunciation to the shepherds peripherally, in the upper left corner, even though it represents an episode occurring prior to the main scene. Similarly, in the Nativity at Night of Geertgen tot Sint Jans, the annunciation to the shepherds is seen on a hillside through an opening in the stable wall.

Scenes showing the shepherds at the side of the crib are a different subject, formally known as the Adoration of the shepherds. This is very commonly combined with the Adoration of the Magi, which makes for a balanced composition, as the two groups often occupy opposite sides of the image space around the central figures, and fitted with the theological interpretation of the episode, where the two groups represented the peoples of the world between them. This combination is first found in the 6th-century Monza ampullae made in Palestine.

The landscape varies, though scenes in the background of a Nativity very often show the shepherds on a steep hill, making visual sense of their placement above the main Nativity scene. The number of shepherds shown varies also,[18] though three is typical in the West; one or more dogs may be included, as in the Taddeo Gaddi (right, with red collar). The annunciation to the shepherds became less common as an independent subject in the late Middle Ages,[18] but depictions continued in later centuries. Famous depictions by Abraham Hondius and Rembrandt exist. Along with the Agony in the Garden and the Arrest of Christ the scene was one of those used most often in the development of the depiction of night scenes, especially in 15th century Early Netherlandish painting and manuscript illustration (see illustrations here and the Geertgen tot Sint Jans linked above).

In Renaissance art, drawing on classical stories of Orpheus, the shepherds are sometimes depicted with musical instruments.[19] A charming but atypical miniature in the La Flora Hours in Naples shows the shepherds playing to the Infant Jesus, as a delighted Virgin Mary stands to one side.

Music

[edit]Christmas cantatas often deal with the Annunciation. It features prominently in both Bach's Und es waren Hirten in derselben Gegend, Part II of Bach's Christmas Oratorio, and in Part I of Handel's Messiah.

Christmas carols

[edit]Many Christmas carols mention the annunciation to the shepherds, with the Gloria in Excelsis Deo being the most ancient. Phillips Brooks' "O Little Town of Bethlehem" (1867) has the lines "O morning stars together, proclaim the holy birth, / And praises sing to God the King, and peace to men on earth!" The originally German carol "Silent Night" has "Shepherds quake at the sight; / Glories stream from heaven afar, / Heavenly hosts sing Alleluia!" However, this is a free translation of the German, which says "Hirten erst kund gemacht / durch der Engel Halleluja ... That is "Shepherds heard the news first, through (by means of) the angels' Halleluja. No mention of shepherds quailing or quaking, nor of 'Glories streaming from heaven afar'. The German does go on to say the song sounds loudly from far and near - "tönt es laut von fern und nah ..."

The episode plays a much greater role in Charles Wesley's "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing" (1739), which begins:

Hark! The herald angels sing,

"Glory to the newborn King;

Peace on earth, and mercy mild,

God and sinners reconciled!"

Joyful, all ye nations rise,

Join the triumph of the skies;

With th'angelic host proclaim,

"Christ is born in Bethlehem!"

Nahum Tate's well-known carol "While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks" (1700) is entirely devoted to describing the annunciation to the shepherds, and the episode is also significant in "The First Nowell", Angels from the Realms of Glory, the originally French carol "Angels We Have Heard on High", and several others.

The carol "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day", written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during the American Civil War, reflects on the phrase "Peace on earth, good will to men" in a pacifist sense, as does "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear".[20]

The German carol "Kommet, ihr Hirten" (Come, you Shepherds) reflects the Annunciation and the Adoration of the shepherds.

In popular culture

[edit]The phrase "Peace on earth, good will to men" has been widely used in a variety of contexts. For example, Samuel Morse's farewell message in 1871 read "Greetings and thanks to the telegraph fraternity throughout the world. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good will to men. – S. F. B. Morse."[21]

Linus van Pelt recites the scene verbatim at the climax of A Charlie Brown Christmas, explaining that "that's what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown".

The novelty song "I Yust Go Nuts at Christmas" uses the line to juxtapose the meaning of the holiday with the often chaotic nature of the celebrations; as Gabriel Heatter preaches the annunciation of peace and good will, "(just) at that moment, someone slugs Uncle Ben."

Image gallery

[edit]-

Joachim Wtewael, Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1606

-

Jules Bastien-Lepage, The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1875

-

Carl Bloch, The Sheperds and the angel, 1879

-

Heinrich Vogeler, The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1902

-

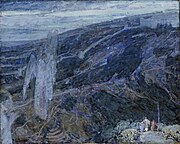

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, 1910

-

Tiffany stained-glass window, c. 1910

-

Window at St. Matthew's, 1912

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Luke 2:11–12, NIV (BibleGateway).

- ^ a b Luke 2:14, NIV (BibleGateway).

- ^ Luke 2:14, KJV (BibleGateway).

- ^ a b Aland, Kurt; Barbara Aland (1995). The text of the New Testament: an introduction to the critical editions and to the theory and practice of modern textual criticism. Eerdmans. pp. 288–289. ISBN 0-8028-4098-1.

- ^ a b c Marshall, I. Howard, The Gospel of Luke: A commentary on the Greek text, Eerdmans, 1978, ISBN 0-8028-3512-0, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Green, Joel B., The Gospel of Luke, Eerdmans, 1997, ISBN 0-8028-2315-7, p. 129.

- ^ a b Aland, Kurt; Black, Matthew; Martini, Carlo M; Metzger, Bruce M.; Wikgren, Allen (1983). The Greek New Testament, 3rd edition. Stuttgart: United Bible Societies. pp. xv, xxvii, and 207. ISBN 3-438-05113-3.

- ^ Aland and Aland, p. 233.

- ^ The erasure is visible in the online Codex Sinaiticus at the top left of the relevant page, at the end of the sixth line of the first column Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. See also here for a manuscript comparison tool.

- ^ Luke 2:14, ESV (BibleGateway).

- ^ Douay-Rheims Bible online (Luke 2), from the Latin "in terra pax in hominibus bonae voluntatis."

- ^ New American Bible online (Luke 2).

- ^ See also here for a comparison of many other translations.

- ^ Luke 1:52, NIV (BibleGateway).

- ^ Marshall, p. 112.

- ^ Green, p. 137.

- ^ Paoletti, John T. and Gary M. Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy, 3rd edition, Laurence King Publishing, 2005, ISBN 1-85669-439-9, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Ross, Leslie, Medieval Art: A topical dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, ISBN 0-313-29329-5, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Earls, Irene, Renaissance Art: A topical dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1987, ISBN 0-313-24658-0, p. 18.

- ^ Browne, Ray B. and Browne, Pat, The Guide to United States Popular Culture, Popular Press, 2001, ISBN 0-87972-821-3, p. 171.

- ^ Lewis Coe, The Telegraph: A history of Morse's invention and its predecessors in the United States, McFarland, 2003, ISBN 0-7864-1808-7, p. 36.