Amate

Amate (Spanish: amate [aˈmate] from Nahuatl languages: āmatl [ˈaːmat͡ɬ]) is a type of bark paper that has been manufactured in Mexico since the precontact times. It was used primarily to create codices.

Amate paper was extensively produced and used for both communication, records, and ritual during the Triple Alliance; however, after the Spanish conquest, its production was mostly banned[1] and replaced by European paper. Amate paper production never completely died, nor did the rituals associated with it. It remained strongest in the rugged, remote mountainous areas of northern Puebla and northern Veracruz states. Spiritual leaders in the small village of San Pablito, Puebla were described as producing paper with "magical" properties[citation needed]. Foreign academics began studying this ritual use of amate in the mid-20th century, and the Otomi people of the area began producing the paper commercially. Otomi craftspeople began selling it in cities such as Mexico City, where the paper was revived by Nahua painters in Guerrero to create "new" indigenous craft, which was then promoted by the Mexican government.

Through this and other innovations, amate paper is one of the most widely available Mexican indigenous handicrafts, sold both nationally and abroad. Nahua paintings of the paper, which is also called "amate," receive the most attention, but Otomi paper makers have also received attention not only for the paper itself but for crafts made with it such as elaborate cut-outs.

True paper

[edit]There is some uncertainty as to whether or not the Mesoamerican paper can be considered true paper owing to the thorough destruction of their civilization by the Spanish. The Maya used a writing material called huun starting from the 5th century. It was made from the inner bark of the wild fig tree. It was cut and stretched thin rather than made of randomly woven fibers, which according to one source, disqualified it as true paper. The Maya made codices out of huun. The Toltecs and Aztecs also had their own form of paper.[2] The Aztec amatl (amate) was used for writing, decorations, rituals, and as material for masks. Aztec paper, like Maya paper, is not considered true paper by some. Like its predecessors, it was made from the inner bark of the wild fig tree, beaten, stretched, and dried. There are also records of paper made from agave, which was coarse and bumpy, and was probably used for purposes other than writing.[3] After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Aztecs began using paper imported by the Spanish for works such as the Codex Mendoza. There were 42 amate producing Aztec villages prior to the Spanish Conquest, all of which have ceased their operations by the modern day. The Otomi people in Mexico still make amate today but have trouble meeting demand due to a dwindling supply of fig and mulberry trees, which are in danger of extinction.[4]

History

[edit]Amate paper has a long history. This history is not only because the raw materials for its manufacture have persisted but also that the manufacture, distribution and uses have adapted to the needs and restrictions of various epochs. This history can be roughly divided into three periods: the pre-Hispanic period, the Spanish colonial period to the 20th century, and from the latter 20th century to the present, marked by the paper's use as a commodity.[5]

Pre-Hispanic period

[edit]

The development of paper in Mesoamerica parallels that of ancient China, which used mulberry pulp for paper, as well as ancient Egypt, which used papyrus.[6] It is not known exactly where or when papermaking began in Mesoamerica.[7][8]

The oldest known amate paper dates back to 75 CE. It was discovered at the site of Huitzilapa, Jalisco. Huitzilapa is a shaft tomb culture site located northwest of Tequila Volcano near the town of Magdalena. The crumpled piece of paper was found in the southern chamber of the site's shaft tomb, possibly associated with a male scribe. Rather than being produced from Trema micrantha from which modern amate is made, the amate found at Huitzilapa is made from Ficus tecolutensis (now F. aurea).[9] Iconography (in stone) dating from the period contains depictions of items thought to be paper. For example, Monument 52 from the Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán illustrates an individual adorned with ear pennants of folded paper.[10] The oldest known surviving book made from amate paper may be the Grolier Codex, which Michael D. Coe and other researchers have asserted is authentic and dated to the 12th–13th century CE.[11]

Arguments from the 1940s to the 1970s have centered on a time of 300 CE of the use of bark clothing by the Maya people. Ethnolinguistic studies lead to the names of two villages in Maya territory that relate the use of bark paper, Excachaché ("place where white bark trusses are smoothed") and Yokzachuún ("over the white paper"). Anthropologist Marion mentions that in Lacandones, in Chiapas, the Maya were still manufacturing and using bark clothing in the 1980s. For these reason, it was probably the Maya who first propagated knowledge about bark-paper-making and spread it throughout southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador, when it was at its height in the pre-classic period.[12][13] However, according researcher Hans Lenz, this Maya paper was likely not the amate paper known in later Mesoamerica.[8] The Mayan language word for book is hun [hun].[14]

Amate paper was used most extensively during the Triple Alliance Empire.[15] This paper was manufactured in over 40 villages in territory controlled by the Aztecs and then handed over as tribute by the conquered peoples. This amounted to about 480,000 sheets annually. Most of the production was concentrated in the modern state of Morelos, where Ficus trees are abundant because of the climate.[8][13][16] This paper was assigned to the royal sector, to be used as gifts on special occasions or as rewards for warriors. It was also sent to the religious elites for ritual purposes. The last share was allotted to royal scribes for the writing of codices and other records.[17]

Little is known about the paper's manufacture in the pre-Hispanic period. Stone beaters dating from the 6th century CE have been found, and these tools are most often found where amate trees grow. Most are made of volcanic stone with some made of marble and granite. They are usually rectangular or circular with grooves on one or both sides to macerate the fibers. These beaters are still used by Otomi artisans, and almost all are volcanic, with an additional groove added on the side to help hold the stone. According to some early Spanish accounts, the bark was left overnight in water to soak, after which the finer inner fibers were separated from coarser outer fibers and pounded into flat sheets. But it is not known who did the work, or how the labor was divided.[18]

As a tribute item, amate was assigned to the royal sector because it was not considered to be a commodity. This paper was related to power and religion, the way through which the Aztecs imposed and justified their dominance in Mesoamerica. As tribute, it represented a transaction between the dominant groups and the dominated villages. In the second phase, the paper used by the royal authorities and priests for sacred and political purposes was a way to empower and frequently register all the other sumptuary exclusive things.[19]

Amate paper was created as part of a line of technologies to satisfy the human need to express and communicate. It was preceded by stone, clay and leather to transmit knowledge first in the form of pictures, and later with the Olmecs and Maya through a form of hieroglyphic writing.[12] Bark paper had important advantages as it is easier to obtain than animal skins and was easier to work than other fibers. It could be bent, shirred, glued and melded for specific finishing touches and for decoration. Two more advantages stimulated the extensive use of bark paper: its light weight and its ease of transport, which translated into great savings in time, space and labor when compared with other raw materials.[20] In the Aztec era, paper retained its importance as a writing surface, especially in the production of chronicles and the keeping of records such as inventories and accounting. Codices were converted into "books" by folding into an accordion pattern. Of the approximately 500 surviving codices, about 16 date to before the conquest and 4 are made of bark paper. These include the Dresden Codex from the Yucatán, the Fejérváry-Mayer Codex from the Mixteca region and the Borgia Codex from Oaxaca.[21]

However, paper also had a sacred aspect and was used in rituals along with other items such as incense, copal, maguey thorns and rubber.[21] For ceremonial and religious events, bark paper was used in various ways: as decorations used in fertility rituals, yiataztli, a kind of bag, and as an amatetéuitl, a badge used to symbolize a prisoner's soul after sacrifice. It was also used to dress idols, priests and sacrifice victims in forms of crowns, stoles, plumes, wigs, trusses and bracelets. Paper items such as flags, skeletons and very long papers, up to the length of a man, were used as offerings, often by burning them.[22] Another important paper item for rituals was paper cut in the form of long flags or trapezoids and painted with black rubber spots to depict the characteristic of the god being honored. At a certain time of year, these were also used to ask for rain. At this time, the papers were colored blue with plumage at the spearhead.[23]

Colonial period to 20th century

[edit]When the Spanish arrived, they noted the production of codices and paper, which was also made from maguey and palm fibers as well as bark. It was specifically noted by Pedro Mártir de Anglería.[24] After the Conquest, indigenous paper, especially bark paper lost its value as a tribute item not only because the Spanish preferred European paper but also because bark paper's connection to indigenous religion caused it to be banned.[16] The justification for the banning of amate was that it was used for magic and witchcraft.[8] This was part of the Spaniard's efforts to mass convert the indigenous to Catholicism, which included the mass burning of codices, which contained most of the native history as well as cultural and natural knowledge.[15]

Only 16 of 500 surviving codices were written before the Conquest. The other, post-conquest books were written on bark paper although a few were written on European paper, cotton, or animal hides. They were largely the work of missionaries, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, who were interested in recording the history and knowledge of the indigenous people. Some of the important codices of this type include Codex Sierra, Codex La Cruz Badiano and Codex Florentino. The Codex Mendocino was commissioned by viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in 1525 to learn about the tribute system and other indigenous practices to be adapted to Spanish rule. However, it is on European paper.[25]

Although bark paper was banned, it did not completely disappear. In the early colonial period, there was a shortage of European paper, which made it necessary to use the indigenous version on occasion.[25] During the evangelization process, amate, along with a paste made from corn canes was appropriated by missionaries to create Christian images, mostly in the 16th and 17th century.[13][26] In addition, among the indigenous, paper continued to be made clandestinely for ritual purposes. In 1569, friar Diego de Mendoza observed several indigenous carrying offerings of paper, copal and woven mats to the lakes inside the Nevado de Toluca volcano as offerings.[26] The most successful at keeping paper making traditions alive were certain indigenous groups living in the La Huasteca, Ixhuatlán and Chicontepec in the north of Veracruz and some villages in Hidalgo. The only records of bark paper making after the early 1800s refer to these areas.[15][27] Most of these areas are dominated by the Otomi and the area's ruggedness and isolation from central Spanish authority allowed small villages to keep small quantities of paper in production. In fact, this clandestine nature helped it to survive as a way to defy Spanish culture and reaffirm identity.[19]

Later 20th century to the present

[edit]

By the mid-20th century, the knowledge of making amate paper was kept alive only in a few small towns in the rugged mountains of Puebla and Veracruz states, such as San Pablito, an Otomi village and Chicontepec, a Nahua village.[8][28] It was particularly strong in San Pablito in Puebla as many of the villages around it believed this paper has special power when used in rituals.[29] The making of paper here until the 1960s was strictly the purview of the shamans, who kept the process secret, making paper primarily to be used for cutting gods and other figures for ritual. However, these shamans came into contact with anthropologists, learning of the interest that people on the outside had for their paper and their culture.[30] But although the ritual cutting of paper remained important for the Otomi people of northern Puebla, the use of amate paper was declining, with industrial paper or tissue paper replacing amate paper in rituals.[31] One stimulus for amate's commercialization was the shamans' growing realization of the commercial value of the paper; they began to sell cutouts of bark paper figures on a small scale in Mexico City along with other Otomi handcrafts.[30]

What the sale of these figures did was to make the bark paper a commodity. The paper was not sacred until and unless a shaman cut it as part of a ritual. The making of the paper and non-ritualistic cutting did not interfere with the ritual aspects of paper in general. This allowed a product formerly reserved only for ritual to become something with market value as well. It also allowed the making of paper to become open to the population of San Pablito and not only to shamans.[32]

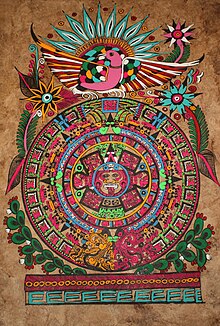

However, most amate paper is sold as the backing for paintings made by Nahua artists from Guerrero state. There are various stories as to how painting on bark paper came about but they are divided between whether it was a Nahua or an Otomi idea. However, it is known that both Nahua and Otomi sold crafts at the Bazar del Sábado in San Ángel in Mexico City in the 1960s. The Otomi were selling paper and other crafts and the Nahua were selling their traditionally painted pottery.[33][34] The Nahua transferred many of their pottery painting designs onto amate paper, which is easier to transport and sell.[35] The Nahua called the paintings by their word for bark paper, which is "amatl." Today, the word is applied to all crafts which use the paper. The new painting form found great demand from the start, and at first, the Nahua would buy almost all of the Otomi's paper production. Painting on bark paper quickly spread to various villages in Guerrero and by the end of the 1960s, became the most important economic activity in eight Nahua villages Ameyaltepec, Oapan, Ahuahuapan, Ahuelican, Analco, San Juan Tetelcingo, Xalitla and Maxela. (page 106) Each Nahua village has its own painting styles developed from the tradition of painting ceramics, and this allowed works to be classified.[35]

The rise of amate paper occurred during a time when government policies towards rural indigenous people and their crafts were changing, with the latter being encourage especially to help develop the tourism industry.[33] FONART became part of the consolidation of distribution efforts for amate paper. Much of this involved buying all of the Otomi production of bark paper to ensure that the Nahua would have sufficient supplies. Although this intervention lasted for only about two years, it was crucial for developing sales of amate crafts in national and international markets.[36]

Since then, while the Nahua are still the principle buyers of Otomi amate paper, the Otomi have since branched out into different types of paper and have developed some of their own products to sell. Today, amate paper is one of the most widely distributed Mexican handcrafts nationally and internationally.[35] It has received artistic and academic attention at both levels as well. In 2006, an annual event called the Encuentro de Arte in Papel Amate was begun in the village, which includes events such as processions, Dance of the Voladors, Huapango music and more. The main event is the exhibition of works by various artists such as Francisco Toledo, Sergio Hernández, Gabriel Macotela, Gustavo MOnrroy, Cecilio Sánchez, Nicolás de Jesús, David Correa, Héctor Montiel, José Montiel, Laura Montiel, Santiago Regalado Juan Manuel de la Rosa, Ester González, Alejandra Palma Padilla, Nicéforo Hurbieta Moreles, Jorge Lozano and Alfonso García Tellez.[37] The Museo de Arte Popular and the Egyptian embassy in Mexico held an exhibition in 2008 on amate and papyrus with over sixty objects on display comparing the two ancient traditions.[13] One of the most noted artists in the medium is shaman Alfonso Margarito García Téllez, who has exhibited his work in museums such as the San Pedro Museo de Arte in Puebla.[38]

San Pablito

[edit]While amate is made in a few small villages in northern Puebla, northern Veracruz and southern Hidalgo state, only San Pablito in Puebla manufactures the paper commercially.[7] San Pablito is a village in the municipality of Pahuatlán located in the Sierra Norte de Puebla. Tulancingo, Hidalgo is the closest urban center. The area is very mountainous and the village itself is on the side of a mountain called the Cerro del Brujo.[26][34] The making of the paper is the primary economic activity of the community and has alleviated poverty in the village. Before the villagers only had very small houses made of wood, but now they have much larger houses made of block.[34] The paper makers here guard the process greatly and will sever contact with anyone seeking to replicate their work.[39] In addition to providing income to the paper makers themselves the craft has been employing an increasing number of people to harvest bark, over an area which now extends over 1,500km2 in the Sierra Norte de Puebla region.[7] The village manufactures large quantities of paper, still using mostly pre-Hispanic technology and various tree species for raw material. About half of this paper production is still sold to Nahua painters in Guerrero.[7][40]

Paper making has not only brought money into the Otomi population of the community but political clout as well. It is now the most important community economically in the municipality of Pahuatlán, and the last three municipal governments have been headed by an Otomi, which had not happened before.[34][41] However, most of the paper making is done by women. One reason for this is that many men still migrate out of the community to work, mostly to the United States. These two sources of income are combined in many households in San Pablito.[35][42] The economic problems of the late 2000s cut sales by about half forcing more to migrate out for work. Before the crisis, the inhabitants of the village were making two thousand sheets per day.[34]

Ritual use

[edit]While the paper has been commercialized in San Pablito, it has not lost its ritual character here or in other areas such as Texcatepec and Chicontepec, where it is still made for ritual purposes.[8] In these communities, the making and ritual use of paper is similar. Figures are cut from light or dark paper, which each figure and each color having significance. There are two types of paper. Light or white paper is used for images of gods or humans. Dark paper is connected with evil characters or sorcery.[43] In Chicontepec, the light paper is made from mulberry trees, and the dark paper is made from classic amate or fig trees. The older the tree the darker the paper.[8]

Ritual paper acquires a sacred value only when shamans cut it ritually.[44] The cutting technique is most important, not necessarily artistic although many have aesthetic qualities.[8] In San Pablito, the cut outs are of gods or supernatural beings related to the indigenous worldview, but never of Catholic figures. Most of the time, the cut out ceremonies relate to petitions such as good crops and health, although as agriculture declines in importance economically, petitions for health and protection have become more important. One particularly popular ceremony is related to young men who have returned from working abroad.[43][44] In Chicontepec, there are cut outs related to gods or spirits linked to natural phenomena such as lightning, rain, mountains, mangos seeds and more, with those cut from dark paper called "devils" or represent evil spirits. However, figures can also represent people living or dead. Those made of light paper represent good spirits and people who make promises. Female figures are distinguished by locks of hair. Some figures have four arms and two heads in profile, and other have the head and tail of an animal. Those with shoes represent mestizos or bad people who have died in fights, accidents or by drowning, also women who have died in childbirth or children who disrespect their parents. Those without shoes represent indigenous people or good people who have died in sickness or old age. Bad spirits represented in dark paper are burned ceremoniously in order to end their bad influence. Those in light paper are kept as amulets.[8]

The origin of the use of these cut outs is not known. It may extend back to the pre-Hispanic period, but there are now 16th century chronicles documenting the practice. It may have been a post Conquest invention, after the Spanish destroyed all other forms of representing the gods. It was easy to carry, mold, make and hide. Many of the religious concepts related to the cut outs do have pre-Hispanic roots. However, during the colonial period, the Otomi, especially of San Pablito were accused numerous times of witchcraft involving the use of cut outs.[45] Today, some cut out figures are being reinterpreted and sold as handcraft products or folk art, and the use of industrial paper for ritual is common as well. Cut outs made for sale often relate to gods of agriculture, which are less called upon in ritual. These cut outs are also not exactly the same as those made for ritual, with changes made in order to keep the ritual aspect separate.[44]

In San Pablito, the making and cutting of paper is not restricted to shamans, as the rest of the villagers may engage in this. However, only shamans may do paper cutting rituals and the exact techniques of paper making is guarded by the residents of the village from outsiders.[35] The best known shaman related to cut out ritual is Alfonso García Téllez of San Pablito.[6][46] He strongly states that the cutting rituals are not witchcraft, but rather a way to honor the spirits of the natural world and a way to help those who have died, along with their families.[38] García Téllez also creates cut out books about the various Otomi deities, which he has not only sold but also exhibited at museums such as the San Pedro Museo de Arte in Puebla.[38][46]

Amate products

[edit]

Amate paper is one of a number of paper crafts of Mexico, along with papel picado and papier-mâché (such as Judas figures, alebrijes or decorative items such as strands of chili peppers called ristras). However, amate paper has been made as a commodity only since the 1960s. Prior to that time, it was made for mostly ritual purposes.[5][47] The success of amate paper has been as the base for the creation of other products based both in traditional Mexican handcraft designs and more modern uses. Because of the product's versatility, both Otomi artisans and others have developed a number of variations to satisfy the tastes of various handicraft consumers.[48] The paper is sold plain, dyed in a variety of colors and decorated with items such as dried leaves and flowers. Although the Nahua people of Guerrero remain the principal buyers of Otomi paper,[49] other wholesale buyers have used it to create products such as lampshades, notebooks, furniture covers, wallpaper, fancy stationery and more.[50] The Otomi themselves have innovated by creating paper products such as envelopes, book separators, invitation cards as well as cut out figures mostly based on traditional ritual designs. The Otomi have also established two categories of paper, standard quality and that produced for the high-end market, geared to well known Nahua artists and other artists that prize the paper's qualities. This is leading to a number of paper makers to be individually recognized like master craftsmen in other fields.[51]

The Otomi paper makers generally sell their production to a limited number of wholesalers, because of limited Spanish skills and contact with the outside. This means about ten wholesalers controlling the distribution of about half of all Otomi production.[49] These wholesalers, as well as artisans such as the Nahua who use the paper as the basis of their own work, have many more contacts and as a result, retail sales of the product are wide-ranging and varied both within Mexico and abroad.[40] Amate paper products are still sold on the streets and markets in Mexico, much as commercialization of the produce began in the 20th century, often in venues that cater to tourists.[7] However, through wholesalers, the paper also ends up in handicraft stores, open bazaars, specialty shops and the Internet. Much of it is used to create paintings, and the finest of these have been exhibited in both national and international museums and galleries.[7][40] The paper is sold retail in the town to tourists as well as in shops in cities such as Oaxaca, Tijuana, Mexico City, Guadalajara, Monterrey and Puebla. It is also exported to the United States, especially to Miami.[34]

However, about 50 percent of all Otomi paper production is still done in standard 40 cm by 60 cm size and sold to Nahua painters from Guerrero, the market segment which made the mass commercialization of the product possible.[52] Seventy percent of all the craft production of these Otomi and Nahuas is sold on the national market with about thirty percent reaching the international market.[53] As most amate paper is sold as the backing for these paintings, many consumers assume the Nahua produce the paper as well.[54]

The amate paper paintings are a combination of Nahua and Otomi traditions. The Otomi produce the paper, and the Nahua have transferred and adapted painting traditions associated with ceramics to the paper. The Nahuatl word "amate" is applied to both the paper and the paintings done on the paper. Each Nahua village has its own painting style which was developed for ceramics, originally commercialized in Acapulco and other tourist areas as early as the 1940s. The adaption of this painting to amate paper came in the 1960s and quickly spread to various villages until it became the primary economic activity in eight Nahua villages in Guerrero, Ameyaltepec, Oapan, Ahuahuapan, Ahuelican, Analco, San Juan Tetelcingo, Xalitla and Maxela.[55] The paper is that it evokes Mexico's pre-Columbian past in addition to the customary designs painted on it.[56]

The success of these paintings led to the Nahuas buying just about all of the Otomis' paper production in that decade. It also attracted the attention of the government, which was taking an interest in indigenous crafts and promoting them to tourists. The FONART agency became involved for two years, buying Otomi paper to make sure that the Nahua had sufficient supplies for painting. This was crucial for the development of national and international markets for the paintings and the paper.[55] It also worked to validate the "new" craft as legitimate, using symbols of past and present minority peoples as part of Mexican identity.[56]

The paintings started with and still mostly based on traditional designs from pottery although there has been innovation since then. Painted designs began focusing on birds and flowers on the paper. Experimentation led to landscape painting, especially scenes related to rural life such as farming, fishing, weddings, funerals and religious festivals. It even has included the painting of picture frames.[57] Some painters have become famous in their own right for their work. Painter Nicolás de Jesús, from Ameyaltepec has gained international recognition for his paintings, exhibiting abroad in countries such as France, Germany, England and Italy. His works generally touch on themes such as death, oppression of indigenous peoples and various references to popular culture in his local community.[58] Others have innovated ways to speed up the work, such as using silk-screen techniques to make multiple copies.[59]

While the Nahua paintings remain the most important craft form related to amate paper, the Otomi have adopted their elaborate cut out figures to the commercial market as well. This began with shamans creating booklets with miniature cut outs of gods with handwritten explanations. Eventually, these began to sell and this success led to their commercialization in markets in Mexico City, were the Otomi connected with the Nahua in the 1960s.[35] The Otomi still sell cut outs in traditional designs, but have also experimented with newer designs, paper sizes, colors and types of paper.[54] These cut outs include depictions of various gods, especially those related to beans, coffee, corn, pineapples, tomatoes and rain. However, these cut outs are not 100% authentic, with exact replicas still reserved to shamans for ritual purposes. Innovation has included the development of books, and cut outs of suns, flowers, birds, abstract designs from traditional beadwork and even Valentine hearts with painted flowers. Most cut outs are made of one type of paper, then glued onto a contrasting background. Their sizes range from miniatures in booklets to sizes large enough to frame and hang like a painting.[60] The production and sale of these paper products have brought tourism to San Pablito, mostly from Hidalgo, Puebla and Mexico City, but some come from the far north and south of Mexico and even from abroad.[61]

Manufacture

[edit]

While there have been some minor innovations, amate paper is still made using the same basic process that was used in the pre-Hispanic period.[62] The process begins with obtaining the bark for its fiber. Traditionally, these are from trees of the fig (Ficus) family as this bark is the easiest to process. Some large Ficus trees are considered sacred and can be found surrounded with candles and offering of cut amate paper.[41][63] Primary species used include F. cotinifolia, F. padifolia and F. petiolaris, the classic amate tree, along with several non-ficus species such as Morus celtidifolia, Citrus aurantifolia and Heliocarpos donnell-smithii.[10][26] However, the taxonomical identification of trees used for amate paper production is not exact, leading estimates of wild supplies to be inaccurate.[8][64] The softer inner bark is preferred but other parts are used as well.[63] Outer bark and bark from ficus trees tend to make darker paper and inner bark and mulberry bark tends to make lighter paper. Bark is best cut in the spring when it is new, which does less damage. It also is less damaging to take bark from older ficus trees as this bark tends to peel off more easily.[8][58][63] The commercialization of the product has meant that a wider range of area needs to be searched for appropriate trees. This has specialized the harvesting of bark to mostly people from outside San Pablito, with only a few paper makers harvesting their own bark.[65] These bark collectors generally come to the village at the end of the week, but numbers of harvesters and amount of bark can vary greatly, depending on the time of year and other factors.[66] The paper makers generally buy the bark fresh then dry it for storage. After drying, the bark can be conserved for about a year.[59]

From the beginning of commercialization, the making of a paper brought in most of the village's population into the process in one way or another. However, in the 1980s, many men in the area began to leave as migrant workers, mostly to the United States, sending remittances home. This then became the main source of income to San Pablito, and made paper making not only secondary, but mostly done by women.[67] The basic equipment used are stones to beat the fibers, wooden boards, and pans to boil the bark. All of these come from sources outside San Pablito. The stones come from Tlaxcala. The boards come from the two nearby villages of Zoyotla and Honey and the boiling pans are obtained by local hardware stores from Tulancingo.[68]

In the pre-Hispanic period, the bark was first soaked for a day or more to soften it before it was worked. An innovation documented from at least the 20th century is to boil the bark instead, which is faster. To shorten the boiling time, ashes or lime were introduced into the water, later replaced by industrial caustic soda. With the last ingredient, the actual boiling time is between three and six hours, although with set up the process takes anywhere from half to a full day. It can only be done during certain weather conditions (dry days) and it requires constant attention. The amount boiled at one time ranges from 60 to 90 kg with 3.5 kg of caustic soda. The bark needs to be stirred constantly. After boiling, the bark is then rinsed in clean water.[69]

The softened fibers are kept in water until they are processed. This needs to be done as quickly as possible so that they do not rot.[70] At this stage, chlorine bleach may be added to either lighten the paper entirely or to create a mix of shades to create a marbled effect. This step has become necessary due to the lack of naturally light bark fibers.[71] If the paper is to be colored, strong industrial dyes are used. These can vary from purple, red, green or pink, whatever the demand is.[72]

Wooden boards are sized to the paper being made. They are rubbed with soap so that the fibers do not stick. The fibers are arranged on wooden boards and beaten together into a thin flat mass. The best paper is made with long fibers arranged in a grid pattern to fit the board. Lesser quality paper is made from short masses arranged more haphazardly, but still beaten to the same effect.[73] This maceration process liberates soluble carbohydrates that are in the cavities of the cell fibers and act as a kind of glue. The Ficus tree bark contains a high quantity of this substance allowing to make for firm but flexible paper.[63] During the process, the stones are kept moist to keep the paper from sticking to it. The finished flat mass is then usually smoothed over with rounded orange peels. If there are any gaps after the maceration process, these are usually filled in by gluing small pieces of paper.[74]

Remaining on their boards, the pounded sheets are taken outside to dry. Drying times vary due to weather conditions. On dry and sunny days, this can take an hour or two, but in humid conditions it can take days.[75] If the dried sheets are to be sold wholesale, they are then simply bundled. If to be sold retail, the edges are then trimmed with a blade.[76]

The production process in San Pablito has mostly evolved to make paper as quickly as possible, with labor being divided and specialized and new tools and ingredients added towards this end.[77] Almost all production facilities are family based, but the level of organization varies. Most paper making is done inside the home by those who are dedicated to it either full or part-time. If the paper is made only part-time, then the work is done sporadically and usually only by women and children. A more recent phenomenon is the development of large workshops which hire artisans to do the work, supervised by the family which owns the enterprise. These are often established by families who have invested money sent home by migrant worker into materials and equipment.[78] Most of the production of all these facilities is plain sheet of 40 cm by 60 cm, but the larger workshops make the greatest variety of products including giant sheets of 1.2 by 2.4 meters in size.[79]

Ecological concerns

[edit]The commercialization of amate paper has had negative environmental effects. In pre-Hispanic times, bark was taken only from the branches of adult trees, allowing for regeneration.[13] Ficus trees should be optimally no younger than 25 years old before cutting. At that age the bark almost peels off by itself and does less damage to the tree. Other trees such as mulberry do not have to mature as much.[58] The pressure to provide large quantities of bark means that it is taken from younger trees as well.[13] This is negatively affecting the ecosystem of northern Puebla and forcing harvesters to take bark from other species as well as from a wider range, moving into areas such as Tlaxco.[13][34][80]

Another problem is the introduction of caustic soda and other industrial chemicals into the process, which not only gets into the environment and water supply, can also directly poison artisans who do not handle it properly.[80][81]

Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de las Artesanías, the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, the Universidad Veracruzana and the Instituto de Artesanías e Industrias Populares de Puebla have been working on ways to make amate paper making more sustainable. One aspect is to manage the collection of bark. Another is to find a substitute for caustic soda to soften and prepare the fibers without losing quality. Not only is the soda polluting, it has had negative effects on artisans' health. As of 2010, the group has reported advances in its investigations such as ways of including new types of bark from other species.[80][81][82]

In addition, the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social is urging a reforestation plan in order to implement a more sustainable supply of bark.[34]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "AMATES. CORTEZA DE IDENTIDAD". The Mexican Museum. Retrieved 2024-07-02.

- ^ Kurlansky 2016, p. 138-141.

- ^ Kurlansky 2016, p. 142-145.

- ^ Kurlansky 2016, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, pages 8, 80

- ^ a b Lizeth Gómez De Anda (September 30, 2010). "Papel amate, arte curativo" [Amate paper, curative art]. La Razón (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f López Binnqüist, pages 2-7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "El Papel Amate Entre los Nahuas de Chicontepec" [Amate paper among the Nahuas of Chicontepec] (in Spanish). Veracruz, Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Benz et al. 2006

- ^ a b Miller and Taube (1993, p. 131)

- ^ Annalee Newitz (12 September 2016). "Confirmed: Mysterious ancient Maya book, Grolier Codex, is genuine: 900 year-old astronomy guide is oldest known book written in the Americas." Ars Technica. Accessed 12 September 2016.

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 81

- ^ a b c d e f g "Amate y Papiro… un diálogo histórico" [Amate and Papyrus… a historic dialogue]. National Geographic en español (in Spanish). May 2008. Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Boot, E. (2002). A Preliminary Classic Maya-English / English-Classic Maya Vocabulary of Hieroglyphic Readings. Leiden University, the Netherlands. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c López Binnqüist, p. 80

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 90

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 89

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 121–122

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 115

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 83

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 84

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 86

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 87

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 82

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, pages 91-92

- ^ a b c d Beatriz M. Oliver Vega (19 August 2010). "El papel de la tierra en el tiempo" ["Earth" paper over time] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 93-94

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 94

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 94-97

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 104

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 103, 115, 105

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 103, 115, 80

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 106

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tania Damián Jiménez (October 13, 2010). "A punto de extinguirse, el árbol del amate en San Pablito Pahuatlán: Libertad Mora" [A the point of extinction:the amate árbol in San Pablio Pahuatlán:Libertad Mora]. La Jornada del Orienta (in Spanish). Puebla. Retrieved April 15, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f López Binnqüist, page 105

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 107

- ^ Ernesto Romero (April 13, 2007). "Pahuatlán: Una historia en papel amate" [Pahuatlán:history in amate paper]. Periodico Digital (in Spanish). Puebla. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c Paula Carrizosa (December 6, 2010). "Exhiben el uso curativo del papel amate en el pueblo de San Pablito Pahuatlán". El Sur de Acapulco (in Spanish). Acapulco. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 148

- ^ a b c López Binnqüist, page 10

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 9

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 146

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, pages 99–101

- ^ a b c López Binnqüist, page 116

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 101–102

- ^ a b Martínez Álvarez, Luis Alberto (April 24, 2009). "Tributo a las deidades" [Tribute to the gods] (in Spanish). Mexico: State of Puebla. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Helen Bercovitch (June 2001). "The Mexican art forms of ristras, papel amate and papel picado". Mexconnect newsletter. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 80, 2-7, 111

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 135

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 2-7,10,111, 114

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 111, 142

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 111, 135, 142 105

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 142

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 112

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, pages 105–106

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 109

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 110

- ^ a b c Xavier Rosado (December 3, 2002). "El arte en amate, tradición olmeca que continúan indígenas de Guerrero y Puebla" [Art in amate, Olmec tradition that the indigenous of Guerrero and Puebla continue]. El Sur de Acapulco (in Spanish). Acapulco. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b López Binnqüist, page 125

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 113

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 138

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 123-124

- ^ a b c d Alejandro Quintanar-Isáis; Citlalli López Binnqüist; Marie Vander Meeren (2008). El uso del floema secundario en la elaboración de papel amate (PDF) (Report). 1Depto. de Biolog´ıa, UAM-I, Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales, Universidad Veracruzana, Instituto Nacional de Antropolog´ıa e Historia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-22. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 17

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 123

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 8

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 123,125

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 130

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 124-125

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 124, 127

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 126

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 127

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 8, 124, 127

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 12, 129

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 124, 128

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 129

- ^ López Binnqüist, page 117

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 131-132

- ^ López Binnqüist, pages 129,132

- ^ a b c "Nueva tecnología, garantiza producción sustentable de Papel Amate en la Sierra Norte de Puebla" [New technology guarantees sustainable production of Amate paper in the Sierra Norte de Puebla] (Press release) (in Spanish). FONART. April 6, 2011. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b "Investigación interinstitucional garantiza producción sustentable de papel amate" [Inter-institutional research guarantees sustainable production of amate paper] (in Spanish). Mexico: FONART. 2010. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Ángel A. Herrera (September 30, 2010). "Avanza producción sustentable de papel amate en San Pablito" [Sustainable amate paper production advances in San Pablito]. Heraldo de Puebla (in Spanish). Puebla. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

References

[edit]- Kurlansky, Mark (2016), Paper: Paging Through History, W. W. Norton & Co

- Rosaura Citlalli López Binnqüist (2003). The endurance of Mexican amate paper: Exploring additional dimensions to the sustainable development concept (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands. Docket 9036519004. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6.

- Benz, Bruce; Lorenza Lopez Mestas; Jorge Ramos de la Vega (2006). "Organic Offerings, Paper, and Fibers from the Huitzilapa Shaft Tomb, Jalisco, Mexico". Ancient Mesoamerica. Vol. 17, no. 2. pp. 283–296.

Further reading

[edit]- Codex Espangliensis: A modern art codex printed on amatl paper.

External links

[edit]- The Construction of the Codex in Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization by Thomas J. Tobin. Maya codex and paper making.