Western world

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and states in the regions of Western Europe,[a] Northern America, and Australasia;[b] with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America[c] also constitute the West.[2][3] The Western world likewise is called the Occident (from Latin occidens 'setting down, sunset, west') in contrast to the Eastern world known as the Orient (from Latin oriens 'origin, sunrise, east'). The West is considered an evolving concept; made up of cultural, political, and economic synergy among diverse groups of people, and not a rigid region with fixed borders and members.[4] Definitions of "Western world" vary according to context and perspectives.

Some historians contend that a linear development of the West can be traced from Ancient Greece and Rome,[5] while others argue that such a projection constructs a false genealogy.[6][7] A geographical concept of the West started to take shape in the 4th century CE when Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor, divided the Roman Empire between the Greek East and Latin West. The East Roman Empire, later called the Byzantine Empire, continued for a millennium, while the West Roman Empire lasted for only about a century and a half. Significant theological and ecclesiastical differences led Western Europeans to consider the Christians in the Byzantine Empire as heretics. In 1054 CE, when the church in Rome excommunicated the patriarch of Byzantium, the politico-religious division between the Western church and Eastern church culminated in the Great Schism or the East–West Schism.[8] Even though friendly relations continued between the two parts of the Christendom for some time, the crusades made the schism definitive with hostility.[9] The West during these crusades tried to capture trade routes to the East and failed, it instead discovered the Americas.[10] In the aftermath of European colonization of the Americas, an idea of the "Western" world, as an inheritor of Latin Christendom emerged.[11] According to the Oxford English dictionary, the earliest reference to the term "Western world" was from 1586, found in the writings of William Warner.[12]

Countries that are considered to constitute the West vary according to perspective rather than their geographical location. Countries like Australia and New Zealand, located in the Eastern Hemisphere are included in modern definitions of the Western world, as these regions and others like them have been significantly influenced by the British—derived from colonization, and immigration of Europeans—factors that grounded such countries to the West.[13] Depending on the context and the historical period in question, Russia was sometimes seen as a part of the West, and at other times juxtaposed with it.[14][15][16] Running parallel to the rise of the United States as a great power and the development of communication–transportation technologies "shrinking" the distance between both the Atlantic Ocean shores, the US became more prominently featured in the conceptualizations of the West.[14]

Between the eighteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, prominent countries in the West such as the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand have been once envisioned as ethnocracies for Whites.[17][18][19] Racism is cited as a contributing factor to European colonization of the New World, which today constitutes much of the "geographical" Western world.[20][21] Starting from the late 1960s, certain parts of the Western world have become notable for their diversity due to immigration.[22][23] The idea of "the West" over the course of time has evolved from a directional concept to a socio-political concept that had been temporalized and rendered as a concept of the future bestowed with notions of progress and modernity.[14]

Introduction

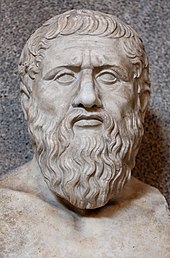

The origins of Western civilization can be traced back to the ancient Mediterranean world. Ancient Greece[d] and Ancient Rome[e] are generally considered to be the birthplaces of Western civilization—Greece having heavily influenced Rome—the former due to its impact on philosophy, democracy, science, aesthetics, as well as building designs and proportions and architecture; the latter due to its influence on art, law, warfare, governance, republicanism, engineering and religion. Western Civilization is also closely associated with Christianity,[42] the dominant religion in the West, with roots in Greco-Roman and Jewish thought. Christian ethics, drawing from the ethical and moral principles of its historical roots in Judaism, has played a pivotal role in shaping the foundational framework of Western societies.[43][44][45] Earlier civilizations, such as the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians, had also significantly influenced Western civilization through their advancements in writing, law codes, and societal structures.[42] The convergence of Greek-Roman and Judeo-Christian influences in shaping Western civilization has led certain scholars to characterize it as emerging from the legacies of Athens and Jerusalem,[46][47][48] or Athens, Jerusalem and Rome.[49]

In ancient Greece and Rome, individuals identified primarily as subjects of states, city-states, or empires, rather than as members of Western civilization. The distinct identification of Western civilization began to crystallize with the rise of Christianity during the Late Roman Empire. In this period, peoples in Europe started to perceive themselves as part of a unique civilization, differentiating from others like Islam, giving rise to the concept of Western civilization. By the 15th century, Renaissance intellectuals solidified this concept, associating Western civilization not only with Christianity but also with the intellectual and political achievements of the ancient Greeks and Romans.[42]

Historians, such as Carroll Quigley in "The Evolution of Civilizations",[50] contend that Western civilization was born around AD 500, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, leaving a vacuum for new ideas to flourish that were impossible in Classical societies. In either view, between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Renaissance, the West (or those regions that would later become the heartland of the culturally "western sphere") experienced a period of decline, and then readaptation, reorientation and considerable renewed material, technological and political development.[51] Classical culture of the ancient Western world was partly preserved during this period due to the survival of the Eastern Roman Empire and the introduction of the Catholic Church; it was also greatly expanded by the Arab importation[52][53] of both the Ancient Greco-Roman and new technology through the Arabs from India and China to Europe.[54][55]

Since the Renaissance, the West evolved beyond the influence of the ancient Greeks and Romans and the Islamic world, due to the successful Second Agricultural, Commercial,[56] Scientific,[57] and Industrial[58] revolutions (propellers of modern banking concepts). The West rose further with the 18th century's Age of Enlightenment and through the Age of Exploration's expansion of peoples of Western and Central European empires, particularly the globe-spanning colonial empires of 18th and 19th centuries.[59] Numerous times, this expansion was accompanied by Catholic missionaries, who attempted to proselytize Christianity.

In the modern era, Western culture has undergone further transformation through the Renaissance, Ages of Discovery and Enlightenment, and the Industrial and Scientific Revolutions.[60][61] The widespread influence of Western culture extended globally through imperialism, colonialism, and Christianization by Western powers from the 15th to 20th centuries. This influence persists through the exportation of mass culture, a phenomenon often referred to as Westernization.[62]

There was debate among some in the 1960s as to whether Latin America as a whole is in a category of its own.[63]

Culture

Western culture, also known as Western civilization, European civilization, Occidental culture, Western society, or simply the West, refers to the internally diverse culture of the Western world. The term "Western" encompasses the social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, belief systems, political systems, artifacts and technologies primarily rooted in European and Mediterranean histories. A broad concept, "Western culture" does not relate to a region with fixed members or geographical confines. It generally refers to the classical era cultures of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome that expanded across the Mediterranean basin and Europe, and later circulated around the world predominantly through colonization and globalization.[64]

Historically, scholars have closely associated the idea of Western culture with the classical era of Greco-Roman antiquity.[65][66] However, scholars also acknowledge that other ancient cultures, like Ancient Egypt, the Phoenician city-states, and several Near-Eastern cultures stimulated and fostered Western civilization.[67][68][69] The Hellenistic period also promoted syncretism, blending Greek, Roman, and Jewish cultures. Major advances in literature, engineering, and science shaped the Hellenistic Jewish culture from which the earliest Christians and the Greek New Testament emerged.[70][71][72] The eventual Christianization of Europe in late-antiquity would ensure that Christianity, particularly the Catholic Church, remained a dominant force in Western culture for many centuries to follow.[73][74][75]

Western culture continued to develop during the Middle Ages as reforms triggered by the medieval renaissances, the influence of the Islamic world via Al-Andalus and Sicily (including the transfer of technology from the East, and Latin translations of Arabic texts on science and philosophy by Greek and Hellenic-influenced Islamic philosophers),[76][77][78] and the Italian Renaissance as Greek scholars fleeing the fall of Constantinople brought ancient Greek and Roman texts back to central and western Europe.[79] Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the modern university,[80][81] the modern hospital system,[82] scientific economics,[83][84] and natural law (which would later influence the creation of international law).[85] European culture developed a complex range of philosophy, medieval scholasticism, mysticism and Christian and secular humanism, setting the stage for the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, which fundamentally altered religious and political life. Led by figures like Martin Luther, Protestantism challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and promoted ideas of individual freedom and religious reform, paving the way for modern notions of personal responsibility and governance.[86][87][88][89]

The Enlightenment in the 17th and 18th centuries shifted focus to reason, science, and individual rights, influencing revolutions across Europe and the Americas and the development of modern democratic institutions. Enlightenment thinkers advanced ideals of political pluralism and empirical inquiry, which, together with the Industrial Revolution, transformed Western society. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the influence of Enlightenment rationalism continued with the rise of secularism and liberal democracy, while the Industrial Revolution fueled economic and technological growth. The expansion of rights movements and the decline of religious authority marked significant cultural shifts. Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of political pluralism, individualism, prominent subcultures or countercultures, and increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and immigration.Historical divisions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

The West of the Mediterranean Region during the Antiquity

The geopolitical divisions in Europe that created a concept of East and West originated in the ancient tyrannical and imperialistic Graeco-Roman times.[90] The Eastern Mediterranean was home to the highly urbanized cultures that had Greek as their common language (owing to the older empire of Alexander the Great and of the Hellenistic successors), whereas the West was much more rural in its character and more readily adopted Latin as its common language. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the beginning of the medieval times (or Middle Ages), Western and Central Europe were substantially cut off from the East where Byzantine Greek culture and Eastern Christianity became founding influences in the Eastern European world such as the East and South Slavic peoples.[citation needed]

Roman Catholic Western and Central Europe, as such, maintained a distinct identity particularly as it began to redevelop during the Renaissance. Even following the Protestant Reformation, Protestant Europe continued to see itself as more tied to Roman Catholic Europe than other parts of the perceived civilized world. Use of the term West as a specific cultural and geopolitical term developed over the course of the Age of Exploration as Europe spread its culture to other parts of the world. Roman Catholics were the first major religious group to immigrate to the New World, as settlers in the colonies of Spain and Portugal (and later, France) belonged to that faith. English and Dutch colonies, on the other hand, tended to be more religiously diverse. Settlers to these colonies included Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, English Puritans and other nonconformists, English Catholics, Scottish Presbyterians, French Huguenots, German and Swedish Lutherans, as well as Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, and Moravians.[citation needed]

Ancient Roman world (6th century BC – AD 395–476)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Ancient Rome (6th century BC – AD 476) is a term to describe the ancient Roman society that conquered Central Italy assimilating the Italian Etruscan culture, growing from the Latium region since about the 8th century BC, to a massive empire straddling the Mediterranean Sea. In its 10-centuries territorial expansion, Roman civilization shifted from a small monarchy (753–509 BC), to a republic (509–27 BC), into an autocratic empire (27 BC – AD 476). Its Empire came to dominate Western, Central and Southeastern Europe, Northern Africa and, becoming an autocratic Empire a vast Middle Eastern area, when it ended. Conquest was enforced using the Roman legions and then through cultural assimilation by eventual recognition of some form of Roman citizenship's privileges. Nonetheless, despite its great legacy, a number of factors led to the eventual decline and ultimately fall of the Roman Empire.[citation needed]

The Roman Empire succeeded the approximately 500-year-old Roman Republic (c. 510–30 BC). In 350 years, from the successful and deadliest war with the Phoenicians began in 218 BC to the rule of Emperor Hadrian by AD 117, ancient Rome expanded up to twenty-five times its area. The same time passed before its fall in AD 476. Rome had expanded long before the empire reached its zenith with the conquest of Dacia in AD 106 (modern-day Romania) under Emperor Trajan. During its territorial peak, the Roman Empire controlled about 5,000,000 square kilometres (1,900,000 sq mi) of land surface and had a population of 100 million. From the time of Caesar (100–44 BC) to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, Rome dominated Southern Europe, the Mediterranean coast of Northern Africa and the Levant, including the ancient trade routes with population living outside. Ancient Rome has contributed greatly to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, technology and language in the Western world, and its history continues to have a major influence on the world today. Latin language has been the base from which Romance languages evolved and it has been the official language of the Catholic Church and all Catholic religious ceremonies all over Europe until 1967, as well as an or the official language of countries such as Italy and Poland (9th–18th centuries).[91][citation needed]

In AD 395, a few decades before its Western collapse, the Roman Empire formally split into a Western and an Eastern one, each with their own emperors, capitals, and governments, although ostensibly they still belonged to one formal Empire. The Western Roman Empire provinces eventually were replaced by Northern European Germanic ruled kingdoms in the 5th century due to civil wars, corruption, and devastating Germanic invasions from such tribes as the Huns, Goths, the Franks and the Vandals by their late expansion throughout Europe. The three-day Visigoths's AD 410 sack of Rome who had been raiding Greece not long before, a shocking time for Greco-Romans, was the first time after almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to a foreign enemy, and St. Jerome, living in Bethlehem at the time, wrote that "The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken."[92] There followed the sack of AD 455 lasting 14 days, this time conducted by the Vandals, retaining Rome's eternal spirit through the Holy See of Rome (the Latin Church) for centuries to come.[93][94] The ancient Barbarian tribes, often composed of well-trained Roman soldiers paid by Rome to guard the extensive borders, had become militarily sophisticated "Romanized barbarians", and mercilessly slaughtered the Romans conquering their Western territories while looting their possessions.[95]

The Roman Empire is where the idea of "the West" began to emerge.[f]

The Eastern Roman Empire, governed from Constantinople, is usually referred to as the Byzantine Empire after AD 476, the traditional date for the fall of the Roman Empire and beginning of the Early Middle Ages. The survival of the Eastern Roman Empire protected Roman legal and cultural traditions, combining them with Greek and Christian elements, for another thousand years. The name Byzantine Empire was first used centuries later, after the Byzantine Empire ended. The dissolution of the Western half, nominally ended in AD 476, but in truth a long process that ended by the rise of Catholic Gaul (modern-day France) ruling from around the year AD 800, left only the Eastern Roman Empire alive. The Eastern half continued to think of itself as the Eastern Roman Empire until AD 610–800, when Latin ceased to be the official language of the empire. The inhabitants called themselves Romans because the term "Roman" was meant to signify all Christians. The Pope crowned Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans of the newly established Holy Roman Empire, and the West began thinking in terms of Western Latins living in the old Western Empire, and Eastern Greeks (those inside the Roman remnant of the old Eastern Empire).[96]

The birth of the European West during the Middle Ages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

In the early 4th century, the central focus of power was on two separate imperial legacies within the Roman Empire: the older Aegean Sea Greek heritage (of Classical Greece) in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the newer most successful Tyrrhenian Sea Latin heritage (of Ancient Latium and Tuscany) in the Western Mediterranean. A turning point was Constantine the Great's decision to establish the city of Constantinople (today's Istanbul) in modern-day Turkey as the "New Rome" when he picked it as capital of his Empire (later called "Byzantine Empire" by modern historians) in AD 330.

This internal conflict of legacies had possibly emerged since the assassination of Julius Caesar three centuries earlier, when Roman imperialism had just been born with the Roman Republic becoming "Roman Empire", but reached its zenith during 3rd century's many internal civil wars. This is the time when the Huns (part of the ancient Eastern European tribes named barbarians by the Romans) from modern-day Hungary penetrated into the Dalmatian (modern-day Croatia) region then originating in the following 150 years in the Roman Empire officially splitting in two halves. Also the time of the formal acceptance of Christianity as Empire's religious policy, when the Emperors began actively banning and fighting previous pagan religions.

The Eastern Roman Empire included lands south-west of the Black Sea and bordering on the Eastern Mediterranean and parts of the Adriatic Sea. This division into Eastern and Western Roman Empires was later reflected in the administration of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Greek Orthodox churches, with Rome and Constantinople debating over whether either city was the capital of Western religion.[citation needed]

As the Eastern (Orthodox) and Western (Catholic) churches spread their influence, the line between Eastern and Western Christianity was moving. Its movement was affected by the influence of the Byzantine empire and the fluctuating power and influence of the Catholic church in Rome. The geographic line of religious division approximately followed a line of cultural divide.[citation needed]

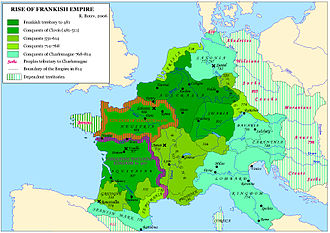

In AD 800 under Charlemagne, the Early Medieval Franks established an empire that was recognized by the Pope in Rome as the Holy Roman Empire (Latin Christian revival of the ancient Roman Empire, under perpetual Germanic rule from AD 962) inheriting ancient Roman Empire's prestige but offending the Eastern Roman Emperor in Constantinople, and leading to the Crusades and the East–West Schism. The crowning of the Emperor by the Pope led to the assumption that the highest power was the papal hierarchy, quintessential Roman Empire's spiritual heritage authority, establishing then, until the Protestant Reformation, the civilization of Western Christendom.[citation needed]

The earliest concept of Europe as a cultural sphere (instead of simple geographic term) is believed to have been formed by Alcuin of York during the Carolingian Renaissance of the 9th century, but was limited to the territories that practised Western Christianity at the time.[97]

The Latin Church of western and central Europe split with the eastern Greek patriarchates in the Christian East–West Schism, also known as the "Great Schism", during the Gregorian Reforms (calling for a more central status of the Roman Catholic Church Institution), three months after Pope Leo IX's death in April 1054.[98] Following the 1054 Great Schism, both the Western Church and Eastern Church continued to consider themselves uniquely orthodox and catholic. Augustine wrote in On True Religion: "Religion is to be sought... only among those who are called Catholic or orthodox Christians, that is, guardians of truth and followers of right."[99] Over time, the Western Christianity gradually identified with the "Catholic" label, and people of Western Europe gradually associated the "Orthodox" label with Eastern Christianity (although in some languages the "Catholic" label is not necessarily identified with the Western Church). This was in note of the fact that both Catholic and Orthodox were in use as ecclesiastical adjectives as early as the 2nd and 4th centuries respectively. Meanwhile, the extent of both Christendoms expanded, as Germanic peoples, Bohemia, Poland, Hungary, Scandinavia, Finnic peoples, Baltic peoples, British Isles and the other non-Christian lands of the northwest were converted by the Western Church, while Eastern Slavic peoples, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, Russian territories, Vlachs and Georgia were converted by the Eastern Orthodox Church.[citation needed]

In 1071, the Byzantine army was defeated by the Muslim Turco-Persians of medieval Asia, resulting in the loss of most of Asia Minor. The situation was a serious threat to the future of the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine Empire. The Emperor sent a plea to the Pope in Rome to send military aid to restore the lost territories to Christian rule. The result was a series of western European military campaigns into the eastern Mediterranean, known as the Crusades. Unfortunately for the Byzantines, the crusaders (belonging to the members of nobility from France, German territories, the Low countries, England, Italy and Hungary) had no allegiance to the Byzantine Emperor and established their own states in the conquered regions, including the heart of the Byzantine Empire.

The Holy Roman Empire would dissolve on 6 August 1806, after the French Revolution and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine by Napoleon.

The decline of the Byzantine Empire (13th–15th centuries) began with the Latin Christian Fourth Crusade in AD 1202–04, considered to be one of the most important events, solidifying the schism between the Christian churches of Greek Byzantine Rite and Latin Roman Rite. An anti-Western riot in 1182 broke out in Constantinople targeting Latins. The extremely wealthy (after previous Crusades) Venetians in particular made a successful attempt to maintain control over the coast of Catholic present-day Croatia (specifically the Dalmatia, a region of interest to the maritime medieval Venetian Republic moneylenders and its rivals, such as the Republic of Genoa) rebelling against the Venetian economic domination.[100] What followed dealt an irrevocable blow to the already weakened Byzantine Empire with the Crusader army's sack of Constantinople in April 1204, capital of the Greek Christian-controlled Byzantine Empire, described as one of the most profitable and disgraceful sacks of a city in history.[101] This paved the way for Muslim conquests in present-day Turkey and the Balkans in the coming centuries (only a handful of the Crusaders followed to the stated destination thereafter, the Holy Land). The geographical identity of the Balkans is historically known as a crossroads of cultures, a juncture between the Latin and Greek bodies of the Roman Empire, the destination of a massive influx of pagans (meaning "non-Christians") Bulgars and Slavs, an area where Catholic and Orthodox Christianity met,[102] as well as the meeting point between Islam and Christianity. The Papal Inquisition was established in AD 1229 on a permanent basis, run largely by clergymen in Rome,[103] and abolished six centuries later. Before AD 1100, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to be heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,[104] and seldom resorting to executions.[105][106][107][108]

This very profitable Central European Fourth Crusade had prompted the 14th century Renaissance (translated as 'Rebirth') of Italian city-states including the Papal States, on eve of the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation (which established the Roman Inquisition to succeed the Medieval Inquisition). There followed the discovery of the American continent, and consequent dissolution of West Christendom as even a theoretical unitary political body, later resulting in the religious Eighty Years War (1568–1648) and Thirty Years War (1618–1648) between various Protestant and Catholic states of the Holy Roman Empire (and emergence of religiously diverse confessions). In this context, the Protestant Reformation (1517) may be viewed as a schism within the Catholic Church. German monk Martin Luther, in the wake of precursors, broke with the pope and with the emperor by the Catholic Church's abusive commercialization of indulgences in the Late Medieval Period, backed by many of the German princes and helped by the development of the printing press, in an attempt to reform corruption within the church.[109][110][111]

Both these religious wars ended with the Peace of Westphalia (1648), which enshrined the concept of the nation-state, and the principle of absolute national sovereignty in international law. As European influence spread across the globe, these Westphalian principles, especially the concept of sovereign states, became central to international law and to the prevailing world order.[112]

Expansion of the West: the Era of Colonialism (15th–20th centuries)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

In the 13th and 14th centuries, a number of European travelers, many of them Christian missionaries, had sought to cultivate trading with Asia and Africa. With the Crusades came the relative contraction of the Orthodox Byzantine's large silk industry in favor of Catholic Western Europe and the rise of Western Papacy. The most famous of these merchant travelers pursuing East–west trade was Venetian Marco Polo. But these journeys had little permanent effect on east–west trade because of a series of political developments in Asia in the last decades of the 14th century, which put an end to further European exploration of Asia: namely the new Ming rulers were found to be unreceptive of religious proselytism by European missionaries and merchants. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Turks consolidated control over the eastern Mediterranean, closing off key overland trade routes.[citation needed]

The Portuguese spearheaded the drive to find oceanic routes that would provide cheaper and easier access to South and East Asian goods, by advancements in maritime technology such as the caravel ship introduced in the mid-1400s. The charting of oceanic routes between East and West began with the unprecedented voyages of Portuguese and Spanish sea captains. In 1492, European colonialism expanded across the globe with the exploring voyage of merchant, navigator, and Hispano-Italian colonizer Christopher Columbus. Such voyages were influenced by medieval European adventurers after the European spice trade with Asia, who had journeyed overland to the Far East contributing to geographical knowledge of parts of the Asian continent. They are of enormous significance in Western history as they marked the beginning of the European exploration, colonization and exploitation of the American continents and their native inhabitants.[g][h] The European colonization of the Americas led to the Atlantic slave trade between the 1490s and the 1800s, which also contributed to the development of African intertribal warfare and racist ideology. Before the abolition of its slave trade in 1807, the British Empire alone (which had started colonial efforts in 1578, almost a century after Portuguese and Spanish empires) was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.[114] The Holy Roman Empire was dissolved in 1806 by the French Revolutionary Wars; abolition of the Roman Catholic Inquisition followed.[citation needed]

Due to the reach of these empires, Western institutions expanded throughout the world. This process of influence (and imposition) began with the voyages of discovery, colonization, conquest, and exploitation of Portugal enforced as well by papal bulls in 1450s (by the fall of the Byzantine Empire), granting Portugal navigation, war and trade monopoly for any newly discovered lands,[115] and competing Spanish navigators. It continued with the rise of the Dutch East India Company by the destabilizing Spanish discovery of the New World, and the creation and expansion of the English and French colonial empires, and others.[citation needed] Even after demands for self-determination from subject peoples within Western empires were met with decolonization, these institutions persisted. One specific example was the requirement that post-colonial societies were made to form nation-states (in the Western tradition), which often created arbitrary boundaries and borders that did not necessarily represent a whole nation, people, or culture (as in much of Africa), and are often the cause of international conflicts and friction even to this day. Although not part of Western colonization process proper, following the Middle Ages Western culture in fact entered other global-spanning cultures during the colonial 15th–20th centuries.[citation needed] Historically colonialism had been justified with the values of individualism and enlightenment.[116]

The concepts of a world of nation-states born by the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, coupled with the ideologies of the Enlightenment, the coming of modernity, the Scientific Revolution[117] and the Industrial Revolution,[118] would produce powerful social transformations, political and economic institutions that have come to influence (or been imposed upon) most nations of the world today. Historians agree that the Industrial Revolution has been one of the most important events in history.[119]

The course of three centuries since Christopher Columbus' late 15th century's voyages, of deportation of slaves from Africa and British dominant northern-Atlantic location, later developed into modern-day United States of America, evolving from the ratification of the Constitution of the United States by thirteen States on the North American East Coast before end of the 18th century.

In the early-19th century, the systematic urbanization process (migration from villages in search of jobs in manufacturing centers) had begun, and the concentration of labor into factories led to the rise in the population of the towns. World population had been rising as well. It is estimated to have first reached one billion in 1804.[120] Also, the new philosophical movement later known as Romanticism originated, in the wake of the previous Age of Reason of the 1600s and the Enlightenment of 1700s. These are seen as fostering the 19th century Western world's sustained economic development.[121] Before the urbanization and industrialization of the 1800s, demand for oriental goods such as porcelain, silk, spices and tea remained the driving force behind European imperialism in Asia, and (with the important exception of British East India Company rule in India) the European stake in Asia remained confined largely to trading stations and strategic outposts necessary to protect trade.[122] Industrialization, however, dramatically increased European demand for Asian raw materials; and the severe Long Depression of the 1870s provoked a scramble for new markets for European industrial products and financial services in Africa, the Americas, Eastern Europe, and especially in Asia (Western powers exploited their advantages in China for example by the Opium Wars).[123] This resulted in the "New Imperialism", which saw a shift in focus from trade and indirect rule to formal colonial control of vast overseas territories ruled as political extensions of their mother countries.[i] The later years of the 19th century saw the transition from "informal imperialism" (hegemony)[j] by military influence and economic dominance, to direct rule (a revival of colonial imperialism) in the African continent and Middle East.[127]

During the socioeconomically optimistic and innovative decades of the Second Industrial Revolution between the 1870s and 1914, also known as the "Beautiful Era", the established colonial powers in Asia (United Kingdom, France, Netherlands) added to their empires also vast expanses of territory in the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Japan was involved primarily during the Meiji period (1868–1912), though earlier contacts with the Portuguese, Spaniards and Dutch were also present in the Japanese Empire's recognition of the strategic importance of European nations. Traditional Japanese society became an industrial and militarist power like the Western British Empire and the French Third Republic, and similar to the German Empire.[verification needed][citation needed]

At the close of the Spanish–American War in 1898 the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam and Cuba were ceded to the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. The US quickly emerged as the new imperial power in East Asia and in the Pacific Ocean area. The Philippines continued to fight against colonial rule in the Philippine–American War.[128]

By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the world population at the time,[129] and by 1920, it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi),[130] 24% of the Earth's total land area.[131] At its apex, the phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" described the British Empire, because its expanse around the globe meant that the sun always shone on at least one of its territories.[132] As a result, its political, legal, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread throughout the Western world.[citation needed] In the aftermath of the Second World War, decolonizing efforts were employed by all Western powers under United Nations (ex-League of Nations) international directives.[citation needed] Most of colonized nations received independence by 1960. Great Britain showed ongoing responsibility for the welfare of its former colonies as member states of the Commonwealth of Nations. But the end of Western colonial imperialism saw the rise of Western neocolonialism or economic imperialism. Multinational corporations came to offer "a dramatic refinement of the traditional business enterprise", through "issues as far ranging as national sovereignty, ownership of the means of production, environmental protection, consumerism, and policies toward organized labor." Though the overt colonial era had passed, Western nations, as comparatively rich, well-armed, and culturally powerful states, wielded a large degree of influence throughout the world, and with little or no sense of responsibility toward the peoples impacted by its multinational corporations in their exploitation of minerals and markets.[133][134] The dictum of Alfred Thayer Mahan is shown to have lasting relevance, that whoever controls the seas controls the world.[135]

Enlightenment (17th–18th centuries)

Eric Voegelin described the 18th-century as one where "the sentiment grows that one age has come to its close and that a new age of Western civilization is about to be born". According to Voeglin the Enlightenment (also called the Age of Reason) represents the "atrophy of Christian transcendental experiences and [seeks] to enthrone the Newtonian method of science as the only valid method of arriving at truth".[136] Its precursors were John Milton and Baruch Spinoza.[137] Meeting Galileo in 1638 left an enduring impact on John Milton and influenced Milton's great work Areopagitica, where he warns that, without free speech, inquisitorial forces will impose "an undeserved thraldom upon learning".[138]

The achievements of the 17th century included the invention of the telescope and acceptance of heliocentrism. 18th century scholars continued to refine Newton's theory of gravitation, notably Leonhard Euler, Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Alexis-Claude Clairaut, Jean Le Rond d'Alembert, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Pierre-Simon de Laplace. Laplace's five-volume Treatise on Celestial Mechanics is one of the great works of 18th-century Newtonianism. Astronomy gained in prestige as new observatories were funded by governments and more powerful telescopes developed, leading to the discovery of new planets, asteroids, nebulae and comets, and paving the way for improvements in navigation and cartography. Astronomy became the second most popular scientific profession, after medicine.[139]

A common metanarrative of the Enlightenment is the "secularization theory". Modernity, as understood within the framework, means a total break with the past. Innovation and science are the good, representing the modern values of rationalism, while faith is ruled by superstition and traditionalism.[140] Inspired by the Scientific Revolution, the Enlightenment embodied the ideals of improvement and progress. Descartes and Isaac Newton were regarded as exemplars of human intellectual achievement. Condorcet wrote about the progress of humanity in the Sketch of the Progress of the Human Mind (1794), from primitive society to agrarianism, the invention of writing, the later invention of the printing press and the advancement to "the Period when the Sciences and Philosophy threw off the Yoke of Authority".[141]

French writer Pierre Bayle denounced Spinoza as a pantheist (thereby accusing him of atheism). Bayle's criticisms garnered much attention for Spinoza. The pantheism controversy in the late 18th century saw Gotthold Lessing attacked by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi over support for Spinoza's pantheism. Lessing was defended by Moses Mendelssohn, although Mendelssohn diverged from pantheism to follow Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in arguing that God and the world were not of the same substance (equivalency). Spinoza was excommunicated from the Dutch Sephardic community, but for Jews who sought out Jewish sources to guide their own path to secularism, Spinoza was as important as Voltaire and Kant.[142]

Cold War (1947–1991)

During the Cold War, a new definition emerged. Earth was divided into three "worlds". The First World, analogous in this context to what was called the West, was composed of NATO members and other countries aligned with the United States.

The Second World was the Eastern bloc in the Soviet sphere of influence, including the Soviet Union (15 republics including the then-occupied and presently independent Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and Warsaw Pact countries like Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, East Germany (now united with Germany), and Czechoslovakia (now split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia).

The Third World consisted of countries, many of which were unaligned with either, and important members included India, Yugoslavia, Finland (Finlandization) and Switzerland (Swiss Neutrality); some include the People's Republic of China, though this is disputed, since the People's Republic of China, as communist, had friendly relations—at certain times—with the Soviet bloc, and had a significant degree of importance in global geopolitics. Some Third World countries aligned themselves with either the US-led West or the Soviet-led Eastern bloc.

A number of countries did not fit comfortably into this neat definition of partition, including Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, and Ireland, which chose to be neutral. Finland was under the Soviet Union's military sphere of influence (see FCMA treaty) but remained neutral and was not communist, nor was it a member of the Warsaw Pact or Comecon but a member of the EFTA since 1986, and was west of the Iron Curtain. In 1955, when Austria again became a fully independent republic, it did so under the condition that it remain neutral; but as a country to the west of the Iron Curtain, it was in the United States' sphere of influence. Spain did not join the NATO until 1982, seven years after the death of the authoritarian Franco.

The 1980s advent of Mikhail Gorbachev led to the end of the Cold War following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Modern definitions

The exact scope of the Western world is somewhat subjective in nature, depending on whether cultural, economic, spiritual or political criteria are employed. It is a generally accepted Western view to recognize the existence of at least three "major worlds" (or "cultures", or "civilizations"), broadly in contrast with the Western: the Eastern world, the Arab and the African worlds, with no clearly specified boundaries. Additionally, Latin American and Orthodox European worlds are sometimes either a sub-civilization within Western civilization or separately considered "akin" to the West.

Many anthropologists, sociologists and historians oppose "the West and the Rest" in a categorical manner.[143] The same has been done by Malthusian demographers with a sharp distinction between European and non-European family systems. Among anthropologists, this includes Durkheim, Dumont, and Lévi-Strauss.[143]

Cultural definition

The Oxford English dictionary noted that the earliest use of the term "Western world" in the English language was in 1586, found in the writings of William Warner.[12]

In modern usage, Western world refers to Europe and to areas whose populations largely originate from Europe, through the Age of Discovery's imperialism.[144][145][146]

In the 20th century, Christianity declined in influence in many Western countries, mostly in the European Union where some member states have experienced falling church attendance and membership in recent years,[147] and also elsewhere. Secularism (separating religion from politics and science) increased. However, while church attendance is in decline, in some Western countries (i.e. Italy, Poland, and Portugal), more than half of the people state that religion is important,[148] and most Westerners nominally identify themselves as Christians (e.g. 59% in the United Kingdom) and attend church on major occasions, such as Christmas and Easter. In the Americas, Christianity continues to play an important societal role, though in areas such as Canada, a low level of religiosity is common due to a European-type secularization. The official religions of the United Kingdom and some Nordic countries are forms of Christianity, while the majority of European countries have no official religion. Despite this, Christianity, in its different forms, remains the largest faith in most Western countries.[149]

Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world, where 70% are Christians.[150] A 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that 76.2% of Europeans, 73.3% in Oceania, and about 86.0% in the Americas (90% in Latin America and the Caribbean and 77.4% in Northern America) described themselves as Christians.[150][151]

Since the mid-twentieth century, the west became known for its irreligious sentiments, following the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution, inquisitions were abolished in the 19th and 20th centuries, this hastened the separation of church and state, and secularization of the Western world where unchurched spirituality is gaining more prominence over organized religion.[152]

Certain parts of the Western world have become notable for their diversity since the late 1960s.[22][23] Earlier, between the eighteenth century to mid-twentieth century, prominent western countries like the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand have been once envisioned as homelands for whites.[17][18][19] Racism has been noted as a contributing factor to Westerners' colonization of the New World, which makes up much of the geographical West today.[20][21]

Countries in the Western world are also the most keen on digital and televisual media technologies, as they were in the postwar period on television and radio: from 2000 to 2014, the Internet's market penetration in the West was twice that in non-Western regions.[153]

Economic definition

The term "Western world" is sometimes interchangeably used with the term First World or developed countries, stressing the difference between First World and the Third World or developing countries. This usage occurs despite the fact that many countries that may be culturally Western are developing countries – in fact, a significant percentage of the Americas are developing countries. It is also used despite many developed countries or regions not being culturally Western (e.g. Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao). Privatization policies (involving government enterprises and public services) and multinational corporations are often considered a visible sign of Western nations' economic presence, especially in Third World countries, and represent a common institutional environment for powerful politicians, enterprises, trade unions and firms, bankers and thinkers of the Western world.[154][155][156][157][158]

Other views

A series of scholars of civilization, including Arnold J. Toynbee, Alfred Kroeber and Carroll Quigley have identified and analyzed "Western civilization" as one of the civilizations that have historically existed and still exist today. Toynbee entered into quite an expansive mode, including as candidates those countries or cultures who became so heavily influenced by the West as to adopt these borrowings into their very self-identity. Carried to its limit, this would in practice include almost everyone within the West, in one way or another. In particular, Toynbee refers to the intelligentsia formed among the educated elite of countries impacted by the European expansion of centuries past. While often pointedly nationalist, these cultural and political leaders interacted within the West to such an extent as to change both themselves and the West.[63]

The theologian and paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin conceived of the West as the set of civilizations descended from the Nile Valley Civilization of Egypt.[159]

Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Said uses the term "Occident" in his discussion of Orientalism. According to his binary, the West, or Occident, created a romanticized vision of the East, or Orient, to justify colonial and imperialist intentions. This Occident-Orient binary focuses on the Western vision of the East instead of any truths about the East. His theories are rooted in Hegel's master-slave dialectic: The Occident would not exist without the Orient and vice versa.[citation needed] Further, Western writers created this irrational, feminine, weak "Other" to contrast with the rational, masculine, strong West because of a need to create a difference between the two that would justify imperialist ambitions, according to the Said-influenced Indian-American theorist Homi K. Bhabha.[citation needed]

The idea of "the West" over the course of time has evolved from a directional concept to a sociopolitical concept, and has been temporalized and rendered as a concept of the future bestowed with notions of progress and modernity.[14]

See also

- Americas

- Anti-Western sentiment

- Atlanticism

- East–West dichotomy

- Far West

- Global Northwest

- Global North and Global South

- Monroe Doctrine

- Western Hemisphere

Notes

- ^ Including Central European countries, Baltics and territories of Western European nations geographically located near the coast of North Africa, such as Madeira and the Canary Islands.

- ^ Comprising Australia and New Zealand, excluding the Pacific island nations.

- ^ Latin America's status as a part of the West is undisputed by most researchers and disputed by others.[1]

- ^ See [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

See [33][34][35][36][37] - ^ See [38][39][40][41]

- ^ By Rome's central location at the heart of the Empire, "West" and "East" were terms used to denote provinces west and east of the capital itself. Therefore, Iberia (Portugal and Spain), Gaul (France), the Mediterranean coast of North Africa (Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) and Britannia were all part of the "West". Greece, Cyprus, Anatolia, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, and Libya were part of the "East". Italy itself was considered central, until the reforms of Diocletian dividing the Empire into true two halves: Eastern and Western.[citation needed]

- ^ Portuguese sailors began exploring the coast of Africa and the Atlantic archipelagos in 1418–19, using recent developments in navigation, cartography and maritime technology such as the caravel, in order that they might find a sea route to the source of the lucrative spice trade.[citation needed] In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa under the sponsorship of Portugal's John II, from which point he noticed that the coast swung northeast (Cape of Good Hope).[citation needed] In 1492 Christopher Columbus would land on an island in the Bahamas archipelago on behalf of the Spanish, and documenting the Atlantic Ocean's routes would be granted a coat of arms by Pope Alexander VI motu proprio in 1502.[citation needed] With the discovery of the American continent or 'New World' in 1492–1493, the European colonial Age of Discovery and exploration was born, revisiting an imperialistic view accompanied by the invention of firearms, while marking the start of the Modern Era. During this long period the Catholic Church launched a major effort to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the Native Americans and others. A 'Modern West' emerged from the Late Middle Ages (after the Renaissance and fall of Constantinople) as a new civilization greatly influenced by the interpretation of Greek thought preserved in the Byzantine Empire, and transmitted from there by Latin translations and emigration of Greek scholars through Renaissance humanism. (Popular typefaces such as italics were inspired and designed from transcriptions during this period.) Renaissance architectural works, revivals of Classical and Gothic styles, flourished during this modern period throughout Western colonial empires. In 1497 Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama made the first open voyage from Europe to India.[citation needed] In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator in the service of the Crown of Castile ('Spain'), found a sea route into the Pacific Ocean.

- ^ In the 16th century, the Portuguese broke the (overland) medieval monopoly of the Arabs and Italians of trade (goods and slaves) between Asia and Europe by the discovery of the sea route to India around the Cape of Good Hope.[113] With the ensuing rise of the rival Dutch East India Company, Portuguese influence in Asia was gradually eclipsed; Dutch forces first established fortified independent bases in the East and then between 1640 and 1660 wrestled some southern Indian ports, and the lucrative Japan trade from the Portuguese. Later, the English and the French established some settlements in India and trade with China, and their own acquisitions would gradually surpass those of the Dutch. In 1763, the British eliminated French influence in India and established the British East India Company as the most important political force on the Indian Subcontinent.

- ^ The Scramble for Africa was the occupation, division, and colonization of African territory by European powers during the period of New Imperialism, between 1881 and 1914. It is also called the 'Partition of Africa' and by some the 'Conquest of Africa'. In 1870, only 10 percent of Africa was under formal Western/European control; by 1914 it had increased to almost 90 percent of the continent, with only Ethiopia (Abyssinia), the Dervish state (a portion of present-day Somalia)[124] and Liberia still being independent.

- ^ In ancient Greece (8th century BC – AD 6th century), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of a city-state over other city-states.[125] The dominant state is known as the hegemon.[126]

Citations

- ^ Espinosa, Emilio Lamo de (4 December 2017). "Is Latin America part of the West?" (PDF). Elcano Royal Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 April 2019.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N. (2008). Western Civilization in World History. Routledge. pp. 88–95. ISBN 9781134374755.

- ^ Espinosa, Emilio Lamo de. "Is Latin America part of the West?". Elcano Royal Institute. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Hunt, Lynn; Martin, Thomas R.; Rosenwein, Barbara H.; Smith, Bonnie G. (2015). The Making of the West: People and Cultures. Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 4. ISBN 978-1457681523.

The making of the West depended on cultural, political, and economic interaction among diverse groups. The West remains an evolving concept, not a fixed region with unchanging borders and members.

- ^

- Cartledge, Paul (2002). The Greeks A Portrait of Self and Others. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191577833.

an ancient culture, that of the Greeks — is both a foundation stone of our own (Western) civilization and at the same time in key respects a deeply alien phenomenon.

- Sharon, Moshe (2004). Studies in Modern Religions, Religious Movements and the Babi-Baha'i Faiths. BRILL Academic Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 978-9004139046.

Side by side with Christianity, the classical Greco-Roman world forms the sound foundation of Western civilization.

- Richard, Carl J. (2010). Why We're All Romans: The Roman Contribution to the Western World. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742567801.

In 1,200 years the tiny village of Rome established a republic, conquered all of the Mediterranean basin and western Europe, lost its republic, and finally, surrendered its empire. In the process the Romans laid the foundation of Western civilization. [...] The pragmatic Romans brought Greek and Hebrew ideas down to earth, modified them, and transmitted them throughout western Europe. [...] Roman law remains the basis for the legal codes of most western European and Latin American countries — Even in English-speaking countries, where common law prevails, Roman law has exerted substantial influence.

- Grant, Michael (1991). The Founders of the Western World: A History of Greece and Rome. New York : Scribner : Maxwell Macmillan International. ISBN 978-0684193038.

- Cartledge, Paul (2002). The Greeks A Portrait of Self and Others. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0191577833.

- ^ Birken, Lawrence (August 1992). "What Is Western Civilization?". The History Teacher. 25 (4): 451–459. doi:10.2307/494353. JSTOR 494353. Archived from the original on 11 July 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Appiah, Kwame Anthony (9 November 2016). "There is no such thing as western civilisation". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023.

- ^ "East-West Schism". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023.

- ^ Ware, Kallistos (1993). The Orthodox Church. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140146561.

But even after 1054 friendly relations between east and west continued. The two parts of Christendom were not yet conscious of a great gulf of separation between them, and people on both sides still hoped that the misunderstandings could be cleared up without too much difficulty. The dispute remained something of which ordinary Christians in east and west were largely unaware. It was the Crusades which made the schism definitive: they introduced a new spirit of hatred and bitterness, and they brought the whole issue down to the popular level.

- ^ Durant, Will; Durant, Ariel (2012). The Lessons of History. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439170199.

The Crusades, like the wars of Rome with Persia, were attempts of the West to capture trade routes to the East; the discovery of America was a result of the failure of the Crusades.

- ^ Peterson, Paul Silas (2019). The Decline of Established Christianity in the Western World. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 9780367891381. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

While "Western Civilization" is a common theme in the curriculum of secondary and tertiary education, there is a great deal of disagreement about what the terms "West" or "Western" world signify. I have defined it as those "religious traditions, institutions, cultures and nations, including their contemporary shared values, that together emerged as the intellectual descendants and transformers of Latin Christendom." Geographically, this entails Western Europe (including Poland and other central European countries), North America and many other parts of the world that share these traditions and histories, or have adopted them. Much of Central and South America seem to reflect these traditions and values.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Western world". www.oed.com. 2017. Archived from the original on 20 August 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2024.

- ^ Peter N. Stearns, Western Civilization in World History, Themes in World History, Routledge, 2008, ISBN 1134374755, pp. 91-95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bavaj, Riccardo (21 November 2011). ""The West": A Conceptual Exploration". academia.edu. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Henry L. (March 1964). "Russia and the West: A Comparison and Contrast". Slavic Review. 23 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/2492370. JSTOR 2492370. S2CID 153551831. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Alexander Lukin. Russia Between East and West: Perceptions and Reality Archived 13 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Brookings Institution. Published on 28 March 2003

- ^ Jump up to: a b

- Pierce, Jason E. (2016). Making the White Man's West: Whiteness and the Creation of the American West. University Press of Colorado. pp. 123–150. ISBN 978-1-60732-396-9. JSTOR j.ctt19jcg63.

Anglo-Americans, from Thomas Jefferson at the beginning of the nineteenth century to Joseph Pomeroy Widney at the century's end, envisioned the West as more than an ordinary place. They dreamed of it as home to a rugged, independent, white population.

- Kaufmann, Eric (2018). Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration and the Future of White Majorities. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780241317105.

Between 1896 and 1928, the Republicans won seven of nine presidential contests. Immigration restriction was an important part of their platform. [...] Ethno-traditional nationalists favour slower immigration in order to permit enough immigrants to voluntarily assimilate into the ethnic majority, maintaining the white ethno-tradition. [...] rapid immigration of ethnic outsiders raises existential questions for the ethnic majority. In this case, around whether the white majority is losing predominance in 'its' perceived homeland.

- Kelkar, Kamala (16 September 2017). "How a shifting definition of 'white' helped shape U.S. immigration policy". PBS News. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022.

By 1790, a Naturalization Act declared that "all male white inhabitants" would become citizens, a time when the country started enforcing its hierarchy of whiteness. [...] while the concept of whiteness has changed since the 18th century, they say that white nationalism has historically been a motivation behind U.S. immigration policy

- "Defining Citizenship". National Museum of American History. 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

1952: Immigration and Nationality Act eliminates race as a bar to immigration or citizenship.

- Ward, Peter (2002). White Canada Forever. McGill-Queen's University Press - MQUP. ISBN 9780773523227. Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- Pierce, Jason E. (2016). Making the White Man's West: Whiteness and the Creation of the American West. University Press of Colorado. pp. 123–150. ISBN 978-1-60732-396-9. JSTOR j.ctt19jcg63.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

- Green, James N.; Skidmore, Thomas (2021). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190068981.

The whitening thesis called for an influx of white, preferably northern-European, blood in order for Brazilian society to achieve its goals to become an advanced nation. To the chagrin of the thesis' supporters, "nonwhite" immigrants started arriving on Brazilian shores, too.

- Goñi, Uki (31 May 2021). "Time to challenge Argentina's white European self-image, black history experts say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022.

"The whitening project was a successful endeavor in terms of the erasure of blackness," said Edwards. [...] Argentina's pro-European immigration policy was initiated under its 1853 constitution

- Green, James N.; Skidmore, Thomas (2021). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190068981.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

- "The Immigration Restriction Act and the White Australia policy". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was a landmark law which provided the cornerstone of the unofficial 'White Australia' policy and aimed to maintain Australia as a nation populated mainly by white Europeans. It included a dictation test of 50 words in a European language, which became the chief way unwanted migrants could be excluded. The policy remained in place for many decades.

- "White New Zealand policy introduced | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

New Zealand's immigration policy in the early 20th century was strongly influenced by racial ideology. The Immigration Restriction Amendment Act 1920 required intending immigrants to apply for a permanent residence permit before they arrived in New Zealand. Permission was given at the discretion of the minister of customs. The Act enabled officials to prevent Indians and other non-white British subjects entering New Zealand.

- "The Immigration Restriction Act and the White Australia policy". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cotter, Anne-Marie Mooney (2016). Culture Clash: An International Legal Perspective on Ethnic Discrimination. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 9781317155867.

In the western world, racism evolved, twinned with the doctrine of white supremacy, and helped fuel the European exploration, conquest and colonization of much of the rest of the world.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jalata, Asafa (2002). Fighting Against the Injustice of the State and Globalization. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 9780312299071.

Western world racism inflated the values of "Europeanness" and "Whiteness" in areas of civilization, human worth, and culture, and deflated the values of "African-ness" and "Blackness".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2006). Western Civilization. Wadsworth. p. 918. ISBN 9780534646028.

Intellectually and culturally, the Western world after 1965 was notable for its diversity and innovation.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Browne, Anthony (3 September 2000). "The last days of a white world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022.

We are near a global watershed - a time when white people will not be in the majority in the developed world — Just 500 years ago, few had ventured outside their European homeland. [...] clearing the way, they settled in North America, South America, Australia, New Zealand and, to a lesser extent, southern Africa. But now, around the world, whites are falling as a proportion of population.

- ^ Ricardo Duchesne (7 February 2011). The Uniqueness of Western Civilization. BRILL. p. 297. ISBN 978-90-04-19248-5.

The list of books which have celebrated Greece as the "cradle" of the West is endless; two more examples are Charles Freeman's The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World (1999) and Bruce Thornton's Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization (2000)

- ^ Chiara Bottici; Benoît Challand (11 January 2013). The Myth of the Clash of Civilizations. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-136-95119-0.

The reason why even such a sophisticated historian as Pagden can do it is that the idea that Greece is the cradle of civilisation is so much rooted in western minds and school curricula as to be taken for granted.

- ^ William J. Broad (2007). The Oracle: Ancient Delphi and the Science Behind Its Lost Secrets. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-14-303859-7.

In 1979, a friend of de Boer's invited him to join a team of scientists that was going to Greece to assess the suitability of the ... But the idea of learning more about Greece — the cradle of Western civilization, a fresh example of tectonic forces at ...

- ^ Maura Ellyn; Maura McGinnis (2004). Greece: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8239-3999-2.

- ^ John E. Findling; Kimberly D. Pelle (2004). Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-313-32278-5.

- ^ Wayne C. Thompson; Mark H. Mullin (1983). Western Europe, 1983. Stryker-Post Publications. p. 337. ISBN 9780943448114.

for ancient Greece was the cradle of Western culture ...

- ^ Frederick Copleston (1 June 2003). History of Philosophy Volume 1: Greece and Rome. A&C Black. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8264-6895-6.

PART I PRE-SOCRATIC PHILOSOPHY CHAPTER II THE CRADLE OF WESTERN THOUGHT:

- ^ Mario Iozzo (2001). Art and History of Greece: And Mount Athos. Casa Editrice Bonechi. p. 7. ISBN 978-88-8029-435-1.

The capital of Greece, one of the world's most glorious cities and the cradle of Western culture,

- ^ Marxiano Melotti (25 May 2011). The Plastic Venuses: Archaeological Tourism in Post-Modern Society. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-4438-3028-7.

In short, Greece, despite having been the cradle of Western culture, was then an "other" space separate from the West.

- ^ Library Journal. Vol. 97. Bowker. April 1972. p. 1588.

Ancient Greece: Cradle of Western Culture (Series), disc. 6 strips with 3 discs, range: 44–60 fr., 17–18 min

- ^ Stanley Mayer Burstein (2002). Current Issues and the Study of Ancient History. Regina Books. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-930053-10-6.

and making Egypt play the same role in African education and culture that Athens and Greece do in Western culture.

- ^ Murray Milner Jr. (8 January 2015). Elites: A General Model. John Wiley & Sons. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7456-8950-0.

Greece has long been considered the seedbed or cradle of Western civilization.

- ^ Slavica viterbiensia 003: Periodico di letterature e culture slave della Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere Moderne dell'Università della Tuscia. Gangemi Editore spa. 10 November 2011. p. 148. ISBN 978-88-492-6909-3.

The Special Case of Greece The ancient Greece was a cradle of the Western culture,

- ^ Kim Covert (1 July 2011). Ancient Greece: Birthplace of Democracy. Capstone. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4296-6831-6.

Ancient Greece is often called the cradle of western civilization. ... Ideas from literature and science also have their roots in ancient Greece.

- ^ Henry Turner Inman. Rome: the cradle of western civilisation as illustrated by existing monuments. ISBN 9781177738538.

- ^ Michael Ed. Grant (1964). The Birth Of Western Civilisation, Greece & Rome. Thames & Hudson. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016 – via Amazon.co.uk.

- ^ HUXLEY, George; et al. "9780500040034: The Birth of Western Civilization: Greece and Rome". AbeBooks.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Athens. Rome. Jerusalem and Vicinity. Peninsula of Mt. Sinai.: Geographicus Rare Antique Maps". Geographicus.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marvin Perry; Myrna Chase; James Jacob; Margaret Jacob; Theodore H. Von Laue (2012). Western Civilization: Since 1400. Cengage Learning. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1-111-83169-1.

- ^ Role of Judaism in Western culture and civilization Archived 9 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, "Judaism has played a significant role in the development of Western culture because of its unique relationship with Christianity, the dominant religious force in the West". Judaism Archived 4 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Religions in Global Society – Page 146, Peter Beyer – 2006

- ^ Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p.40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the Christian era.

- ^ Celermajer, Danielle (2010). "Introduction: Athens and Jerusalem through a Different Lens". Thesis Eleven. 102 (1): 3–5. doi:10.1177/0725513610371046. ISSN 0725-5136. S2CID 147430371. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

The contrast between Athens and Jerusalem, as the twin fonts of Western civilization, is often thought to sum up a number of structural dichotomies...

- ^ Havers, Grant (2004). "Between Athens and Jerusalem: Western otherness in the thought of Leo Strauss and Hannah Arendt". The European Legacy. 9 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1080/1084877042000197921. ISSN 1084-8770. S2CID 143636651. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Brague, Rémi (2009). "Eccentric Culture: A Theory of Western Civilization". philpapers.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

Western culture, which influenced the whole world, came from Europe. But its roots are not there. They are in Athens and Jerusalem... The Roman attitude senses its own incompleteness and recognizes the call to borrow from what went before it. Historically, it has led the West to borrow from the great traditions of Jerusalem and Athens: primarily the Jewish and Christian tradition, on the one hand, and the classical Greek tradition on the other.

- ^ Rosenne, Shabtai (1958). "The Influence of Judaism on the Development of International Law". Netherlands International Law Review. 5 (2): 119–149. doi:10.1017/S0165070X00029685 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2396-9113. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

The fact that modern international law is one of the products of Western European civilization means that it rests, as all that civilization, upon the threefold heritage of the ancient Mediterranean world, the heritage of Rome, Athens and Jerusalem.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "The Evolution of Civilizations – An Introduction to Historical Analysis (1979)". 10 March 2001. p. 84. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "History of Europe – Crisis, Recovery, Resilience". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ H. G. Wells, The Outline of History, Section 31.8, The Intellectual Life of Arab Islam Archived 14 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine "For some generations before Muhammad, the Arab mind had been, as it were, smouldering, it had been producing poetry and much religious discussion; under the stimulus of the national and racial successes it presently blazed out with a brilliance second only to that of the Greeks during their best period. From a new angle and with a fresh vigour it took up that systematic development of positive knowledge, which the Greeks had begun and relinquished. It revived the human pursuit of science. If the Greek was the father, then the Arab was the foster-father of the scientific method of dealing with reality, that is to say, by absolute frankness, the utmost simplicity of statement and explanation, exact record, and exhaustive criticism. Through the Arabs it was and not by the Latin route that the modern world received that gift of light and power."

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (2002). What Went Wrong. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-06-051605-5. "For many centuries the world of Islam was in the forefront of human civilization and achievement ... In the era between the decline of antiquity and the dawn of modernity, that is, in the centuries designated in European history as medieval, the Islamic claim was not without justification."

- ^ "Science, civilization and society". Es.flinders.edu.au. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Richard J. Mayne Jr. "Middle Ages". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ InfoPlease.com Archived 22 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, commercial revolution

- ^ "The Scientific Revolution". Wsu.edu. 6 June 1999. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Eric Bond; Sheena Gingerich; Oliver Archer-Antonsen; Liam Purcell; Elizabeth Macklem (17 February 2003). "Innovations". The Industrial Revolution. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ "How Islam Created Europe; In late antiquity, the religion split the Mediterranean world in two. Now it is remaking the Continent". The Atlantic. May 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "Western culture". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "A brief history of Western culture". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ "Westernization". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cf., Arnold J. Toynbee, Change and Habit. The challenge of our time (Oxford 1966, 1969) at 153–56; also, Toynbee, A Study of History (10 volumes, 2 supplements).

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (2007). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.

the term "Western" — refer to the culture of classical antiquity that arose in Greece and Rome; survived the collapse of the Roman Empire; spread to western and northern Europe; then during the great periods of exploration and colonization of the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries expanded to the Americas, Australia and areas of Asia and Africa; and now exercises global political, economic, cultural, and military power far greater than the size of its territory or population might otherwise suggest.

- ^

- Freeman, Charles (September 2000). The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-029323-4.

The Greeks provided the chromosomes of Western civilization. One does not have to idealize the Greeks to sustain that point. Greek ways of exploring the cosmos, defining the problems of knowledge (and what is meant by knowledge itself), creating the language in which such problems are explored, representing the physical world and human society in the arts, defining the nature of value, describing the past, still underlie the Western cultural tradition

- Cartledge, Paul (2002). The Greeks: A Portrait of Self and Others. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-157783-3.

Greekness was identified with freedom-spiritual and social as well as political-and slavery was equated with being barbarian, [...] 'democracy' was a Greek invention (celebrating its 2,500th anniversary in 1993/4) [...] an ancient culture, that of the Greeks — is both a foundation stone of our own (Western) civilization and at the same time in key respects a deeply alien phenomenon.

- Pagden, Anthony (2008). Worlds at War: The 2,500 - Year Struggle Between East and West. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923743-2.