Žiča

Žiča Monastery | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Манастир - Жича |

| Order | Serbian Orthodox |

| Established | 1207-1217 |

| Dedicated to | Christ the Pantocrator |

| Diocese | Eparchy of Žiča |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Stefan Prvovenčani |

| Important associated figures | Stefan Milutin |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Cultural Monument of Exceptional Importance |

| Designated date | 1947 |

| Site | |

| Location | Trg Jovana Sarića 1, Kraljevo, Serbia |

| Coordinates | 43°41′46.68″N 20°38′44.66″E / 43.6963000°N 20.6457389°E |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | www |

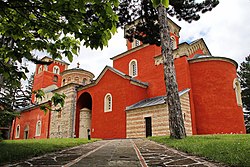

The Žiča Monastery (Serbian: Манастир Жича, romanized: Manastir Žiča, pronounced [ʒîtʃa] or [ʒîːtʃa])[1] is an early 13th-century Serbian Orthodox monastery near Kraljevo, Serbia. The monastery, together with the Church of the Holy Dormition, was built by the first King of Serbia, Stefan the First-Crowned and the first Head of the Serbian Church, Saint Sava.

Žiča was the seat of the Archbishop (1219–1253), and by tradition the coronational church of the Serbian kings, although a king could be crowned in any Serbian church, he was never considered a true king until he was anointed in Žiča. Žiča was declared a Cultural Monument of Exceptional Importance in 1979, and it is protected by Serbia.[2] In 2008, Žiča celebrated 800 years of existence.

Background

[edit]Founding of Serbian Church

[edit]

The Serbs were initially under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Ohrid, under the tutelage of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Rastko Nemanjić, the son of Stefan Nemanja, ruled as Grand Prince of Hum 1190-1192,[3] previously held by Grand Prince Miroslav.[4] In the autumn of 1192 (or shortly thereafter)[5]

Rastko joined Russian monks and traveled to Mount Athos where he took monastic vows and spent several years. In 1195, his father joined him, and together they founded the Chilandar, as the base of Serbian religion.[6] Rastko's father died in Hilandar on 13 February 1199; he was later canonised, as Saint Simeon.[6] Rastko built a church and cell at Karyes, where he stayed for some years, becoming a Hieromonk, then an Archimandrite in 1201. He wrote the Karyes Typicon during his stay there.[6]

He returned to Serbia in 1207, taking the remains of his father with him, which he relocates to the Studenica monastery, after reconciling Stefan Nemanja II with Vukan, who had earlier been in a succession feud. Stefan Nemanja II asked him to remain in Serbia with his clerics. He founded several churches and monasteries, including the Žiča monastery.[6]

Foundation

[edit]The monastery was founded by King Stefan Prvovenčani and Saint Sava,[6] in the Rascian architectural style, between 1208 and 1230, with the help of Greek masters.[7]

Stefan the First-Crowned аlsо ordered that the future Serbian kings аrе tо be crowned at Žičа.[8]

History

[edit]

In 1219, the Serbian Church gains autocephaly, by Emperor Theodore I Laskaris and Patriarch Manuel I of Constantinople, and Archimandrite Sava becomes the first Serbian Archbishop.[9] The monastery acts as the seat of the Archbishop of all Serbian lands. Saint Sava crowning his older brother Stefan Prvovenčani as "King of All Serbia" in the Žiča monastery.[9] In 1221, a synod was held in the Monastery of Žiča, condemning Bogomilism.[7]

When Serbia was invaded by Hungary, Saint Sava sent Arsenije I Sremac to find a safer place in the south to establish a new episcopal See. In 1253 the see was transferred to the Archbishopric of Peć (future Patriarchate) by Arsenije.[10] The Serbian primates had since moved between the two.[11]

In 1289-90, the chief treasures of the ruined monastery, including the remains of Saint Jevstatije I, were transferred to Peć.[12]

In 1219, Žiča became the first seat of the Serbian Archbishopic. The church, dedicated to the Ascension of Our Lord, displays the features of the Raska school. The ground plan is shaped as a spacious nave with a large apse at its eastern end. The central space is domed. The church was built of stone and brick. Architecturally, the Byzantine spirit prevails. There are three layers of painting, each being a separate entity. The earliest frescoes were painted immediately after the first archbishop Sava's return from Nicaea (1219), but only in the choir portions of these have been preserved. Sometime between 1276-92 the Cumans burned the monastery, and King Stefan Milutin renovated it in 1292-1309, during the office of Jevstatije II.[10] Patriarch Nikon joined Despot Đurađ Branković when the capital was moved to Smederevo, following Turkish-Hungarian wars in the territory of Serbia in the 1430s.[11]

Renovation was carried out during the time of Archbishops Jevstatije II (1292-1309), and Nikodim (1317-37), when the refectory was adorned with frescoes, the church covered with a leaden roof, and a tower erected. The new frescoes were painted during the reign of King Milutin, but they have since suffered serious damage. Fragments have survived to the present day on the east wall of the passage beneath the tower (composition of King Stefan Nemanja II and his firstborn son Radoslav), in the narthex, nave and side-chapels.[13]

During the Uprising in Serbia in 1941, the first skirmishes within the Siege of Kraljevo began in the early afternoon on 9 October 1941 near Monastery of Žiča when the Chetnik unit commanded by Milutin Janković attacked German unit which retreated to Kraljevo after a whole day battle in which Germans used canons to shell the monastery.[14] On 10 October German air forces bombarded the Monastery of Žiča using five airplanes and significantly damaged its church.[15] The battle near monastery lasted until early morning of 11 October when Germans broke the rebel lines and put the monastery to fire.[16]

Frescoes

[edit]Frescoes depicting Pantocrator.[17][18]

Gallery

[edit]-

Monastery building.

-

Dormition of the Mother of God, fresco from Žiča.

-

Fresco from Žiča.

-

Church of St. Theodore Stratelates.

See also

[edit]- Studenica

- Sopoćani

- Mileševa

- Visoki Dečani

- Gračanica

- Nemanjić dynasty

- Spatial Cultural-Historical Units of Great Importance

- Tourism in Serbia

- Architecture of Serbia

- There is a village near the Greek city of Ioannina (NW Greece, region of Epirus), also named Zitsa. It was founded during the Late Middle Ages, probably when the Serbs had gained a short-lived control over the Despotate of Epirus, and historians believe that it was named after the monastery.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Pravopisna komisija, ed. (1960). "Žiča". Pravopis srpskohrvatskoga književnog jezika (Fototipsko izdanje 1988 ed.). Novi Sad, Zagreb: Matica srpska, Matica hrvatska. p. 288.

- ^ "Споменици културе у Србији". Spomenicikulture.mi.sanu.ac.rs. 1947-10-25. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ The Late Medieval Balkans, pp. 19–20.

- ^ The Late Medieval Balkans, p. 52

- ^ A. P. Vlasto (2 October 1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval ... p. 218. ISBN 9780521074599. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ a b c d e Đuro Šurmin (1808). "Povjest književnosti hrvatske i srpske". Books.google.com. p. 229. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ a b A. P. Vlasto (2 October 1970). The Entry of the Slavs Into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval ... p. 222. ISBN 9780521074599. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ Kalić, Jovanka (2017). "The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia". Balcanica (XLVIII). Belgrade.

- ^ a b Silvio Ferrari, W. Cole Durham, Elizabeth A. Sewell, Law and religion in post-communist Europe, 2003, p. 295; ISBN 978-90-429-1262-5

- ^ a b [1][dead link]

- ^ a b Stevan K. Pavlowitch (2002). Serbia: The History Behind the Name. p. 11. ISBN 9781850654766. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Radivoje Ljubinković (1975). "The Church of the Apostles in the Patriarchate of Peć". Books.google.com. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Monasteries and churches". Serbia Visit. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Nikolić, Kosta (2003). Dragan Drašković, Radomir Ristić (ed.). Kraljevo in October 1941. Kraljevo: National Museum Kraljevo, Historical Archive Kraljevo. p. 32.

- ^ Nikolić, Kosta (2003). Dragan Drašković, Radomir Ristić (ed.). Kraljevo in October 1941. Kraljevo: National Museum Kraljevo, Historical Archive Kraljevo. p. 32.

- ^ Nikolić, Kosta (2003). Dragan Drašković, Radomir Ristić (ed.). Kraljevo in October 1941. Kraljevo: National Museum Kraljevo, Historical Archive Kraljevo. p. 33.

- ^ Moran, Neil K. (1986). Singers in Late Byzantine and Slavonic Painting: - Neil K. Moran. ISBN 9004078096. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Underwood, Paul Atkins (1967). The Kariya Djami - Paul A. Underwood. ISBN 9780710069320. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ (In Greek) Stephanos Pappas, Formation and Evolution of Communities, Municipalities and the Prefecture of Ioannina, 2004. Original title: Στέφανος Παππάς, Σύσταση και Διοικητική Εξέλιξη των Κοινοτήτων, των Δήμων & του Νομού Ιωαννίνων, λήμμα Δήμος Ζίτσας. Έκδοση ΤΕΔΚ Νομού Ιωαννίνων, 2004; ISBN 960-88395-0-5

Bibliography

[edit]- Јанковић, Марија (1985). Епископије и митрополије Српске цркве у средњем веку [Bishoprics and Metropolitanates of Serbian Church in Middle Ages]. Београд: Историјски институт САНУ.

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal sees in the thirteenth century (Српска епископска седишта у XIII веку)". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654773.

- Stevović, Ivan. "A hypothesis about the earliest phase of Žiča katholikon." Zograf 38 (2014): 45-58.

- Vojvodić, Dragan. "On the trail of the lost frescoes of Žiča." Zograf 34 (2010): 71-86.

- Vojvodić, Dragan. "On the trail of the lost frescoes of Žiča (II)." Zograf 35 (2011): 145-54.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2017). "The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia". Balcanica (48): 7–18. doi:10.2298/BALC1748007K.