2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup bids

| Part of a series on the |

| 2022 FIFA World Cup |

|---|

|

|

|

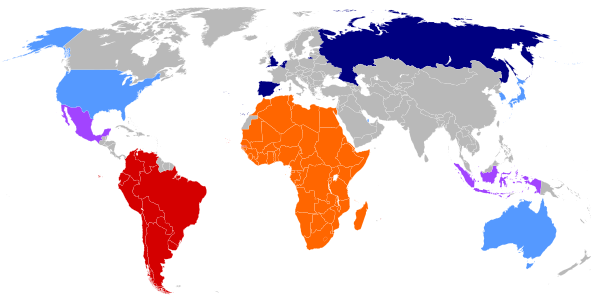

The bidding process for the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups was the process by which the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) selected locations for the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups. The process began officially in March 2009; eleven bids from thirteen countries were received, including one which was withdrawn and one that was rejected before FIFA's executive committee voted in November 2010. Two of the remaining nine bids applied only to the 2022 World Cup, while the rest were initially applications for both. Over the course of the bidding, all non-European bids for the 2018 event were withdrawn, resulting in the exclusion of all European bids from consideration for the 2022 edition. By the time of the decision, bids for the 2018 World Cup included England, Russia, a joint bid from Belgium and Netherlands, and a joint bid from Portugal and Spain. Bids for the 2022 World Cup came from Australia, Japan, Qatar, South Korea, and the United States. Indonesia's bid was disqualified due to lack of governmental support, and Mexico withdrew its bid for financial reasons.

On 2 December 2010, Russia and Qatar were selected as the locations for the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups respectively. The selection process involved several controversies. Two members of the FIFA Executive Committee had their voting rights suspended following allegations that they would accept money in exchange for votes. More allegations of vote buying arose after Qatar's win was announced. Eleven of the 22 committee members who voted on the 2018 and 2022 tournaments have been fined, suspended, banned for life or prosecuted for corruption.

Background

[edit]In October 2007, FIFA ended its continental rotation policy. Instead, countries that are members of the same confederation as either of the last two tournament hosts are ineligible, leaving Africa ineligible for 2018 and South America ineligible for both 2018 and 2022.[1] Other factors in the selection process include the number of suitable stadiums, and their location across candidate nations. Voting is done using a multiple round exhaustive ballot system whereby the candidate receiving the fewest votes in each round is eliminated until a single candidate is chosen by the majority.

Rotation policy

[edit]

Following the selection of the 2006 World Cup hosts, FIFA had decided on a policy for determining the hosts of future editions. The six world confederations — roughly corresponding to continents – would rotate in their turn of providing bids, for a specific edition, from within their member national associations. This system was used only for the selection of the 2010 (South Africa) and 2014 World Cup (Brazil) hosts, open only to CAF and CONMEBOL members, respectively.

In September 2007, the rotation system came under review, and a new system was proposed which renders ineligible for bidding only the last two World Cup host confederations.[2] This proposal was adopted on 29 October 2007, in Zürich, Switzerland by FIFA's executive committee. Under this policy, a 2018 bid could have come from CONCACAF, AFC, UEFA, or OFC, as Africa and South America were ineligible.[3] Likewise, no CONMEBOL member could make a 2022 bid, and candidates from the same confederation as the successful 2018 applicant would be disregarded in the 2022 selection procedure.

The United States, the last non-European candidate in the 2018 bidding cycle, withdrew its bid for that year; hence the 2018 tournament would have to be held in Europe. This in turn meant that CONMEBOL and UEFA were ineligible for 2022.[4][5]

Voting procedure

[edit]For both the 2018 and 2022 editions of the World Cup, the FIFA Executive Committee voted to decide which candidate should host the tournament. The multiple round exhaustive ballot system was used to determine the tournament host. All eligible members of the FIFA Executive Committee had one vote. The candidate country that received the fewest votes in each round was eliminated until a single candidate was chosen by the majority. In the event of a tied vote, FIFA President Sepp Blatter would have had the deciding vote. There are twenty-four members on the committee, but two of those were suspended due to accusations of selling votes.[6]

Schedule

[edit]| Date | Notes[citation needed] |

|---|---|

| 15 January 2009 | Applications formally invited |

| 2 February 2009 | Closing date for registering intention to bid |

| 16 March 2009 | Deadline to submit completed bid registration forms |

| 14 May 2010 | Deadline for submission of full details of bid |

| 19 July 2010 | Four-day individual applicant inspections begin |

| 17 September 2010 | Inspections end[7] |

| 2 December 2010 | FIFA appointed hosts for 2018 and 2022 World Cups |

2018 bids

[edit]Eleven bids were submitted in March 2009 covering thirteen nations, with two joint bids: Belgium-Netherlands and Portugal-Spain. Mexico also submitted a bid, but withdrew theirs on 28 September 2009, while Indonesia had their bid rejected for lack of government support on 19 March 2010.[8] Two of the remaining nine bids, South Korea and Qatar were only for the 2022 World Cup, while all the others bid for both the 2018 and 2022 World Cups.[9] However, due to the withdrawals of the five non-European bids for the 2018 World Cup, making all remaining bids for the 2018 World Cup were from European nations, and FIFA's rules dictate that countries belonging to confederations that hosted either of the two preceding tournaments are not eligible to host,[10] all UEFA bids were forced to be for 2018 only. Four bids came from the Asian Football Confederation (AFC), four from Europe's UEFA, and one from CONCACAF. It had also been reported on the FIFA website that Egypt was entering a bid, but the president of the Egyptian Football Association denied that any more than an inquiry in principle had been made.[11]

| 2018 bids | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 2022 bids |

|||||

| Cancelled bids |

|||||

2018 bid |

2022 bid |

Cancelled bid |

Ineligible in 2018 |

Ineligible in both | |

Belgium and the Netherlands

[edit]Alain Courtois, a Belgian Member of Parliament, announced in October 2006 that a formal bid would be made on behalf of the three Benelux countries: Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.[12] In June 2007 the three countries launched their campaign not as a joint bid in the manner of the Korea-Japan World Cup in 2002, but emphasising it as a common political organisation.[13] Luxembourg would not host any matches or automatically qualify for the finals in a successful Benelux bid, but would host a FIFA congress.[14]

Belgium and the Netherlands registered their intention to bid jointly in March 2009.[15] A delegation led by the presidents of the Belgian and Dutch national football associations met FIFA president Sepp Blatter on 14 November 2007, officially announcing their interest in submitting a joint bid.[16] On 19 March 2008 the delegation also met with UEFA President Michel Platini to convince him that it was a serious offer under one management. Afterwards they claimed to have impressed Platini, who supports the idea of getting the World Cup to Europe.[17] Former French football international Christian Karembeu was presented as official counselor for the joint bid on 23 June 2009.

A factor that was against the Benelux bid was the lack of an 80,000 capacity stadium to host the final.[18] However, the city council of Rotterdam gave permission in March 2009 for development of a new stadium with a capacity of around 80,000 seats to be completed in time for the possible World Cup in 2018. In November 2009, the venues were presented. In Belgium, matches would have been played in 7 venues: Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, Charleroi, Genk, Ghent and Liège. In the Netherlands, only five cities would host matches: Amsterdam, Eindhoven, Enschede, Heerenveen and Rotterdam, but both Amsterdam and Rotterdam would provide two stadiums. Eindhoven would function as the 'capital city' of the World Cup.[19][20] Euro 2000 was also jointly hosted by Belgium and the Netherlands.

England

[edit]On 31 October 2007, The Football Association officially announced its bid to host the event.[21] On 24 April 2008 England finalised a 63-page bid to host the 2018 World Cup, focusing on the development of football worldwide.[22] On 27 January 2009, England officially submitted their bid to FIFA.[23] Richard Caborn led England's bid to stage the event after stepping down as Sports Minister.[24] On 24 October 2008 the Football Association named the executive board to prepare the bid, with David Triesman as the bid chairman.[25] Triesman resigned on 16 May 2010 after comments were published where he suggested that Spain would drop their bid if Russia helped bribe referees in the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and was then replaced by Geoff Thompson.[26]

The British government backed the England 2018 bid. In November 2005, Chancellor Gordon Brown and Sport Minister Tessa Jowell first announced that they were to investigate the possibility of bidding.[27] That month, Adrian Bevington, the Football Association's Director of Communications, announced the support of the Government and the Treasury in the bid, but put off definite proposals.[28] Brown reiterated his support for a bid in March 2006, before England's 2006 World Cup campaign,[29] and again in May 2006.[30] The UK government launched its official report on 12 February 2007, in which it was made clear that its support was for an England-only bid and that all games would be played at English grounds.[31] The venues selected on 16 December 2009 to form the bid were: London (three stadiums), Manchester (two stadiums), Birmingham, Bristol, Leeds, Liverpool, Milton Keynes, Newcastle, Nottingham, Plymouth, Sheffield and Sunderland.[32]

FIFA officials also expressed interest in an English bid. David Will, a vice-president of FIFA, noted England's World Cup proposal as early as May 2004.[33] Franz Beckenbauer, leader of Germany's successful bid for the 2006 World Cup and a member of FIFA's executive committee, twice publicly backed an English bid to host the World Cup, in January and July 2007.[34] [35] FIFA President Sepp Blatter said he would welcome a 2018 bid from "the homeland of football."[36] Blatter met David Cameron on two occasions to discuss the bid while paying visits to England. The British Prime Minister showed much support for the bid and was hopeful that the "home of football" would host the tournament.[37]

In an interview the leader of Russia's bid, Alexei Sorokin, criticised England's bid citing London's high crime rate, alcohol consumption among young people and English fans "inciting ethnic hatred." England filed a complaint, though the complaint was withdrawn following Russia's apology.

Portugal and Spain

[edit]The President of the Portuguese Football Federation (FPF), Gilberto Madail, first proposed a joint bid with Spain in November 2007.[38][39] The bid intent was confirmed by FIFA president, Sepp Blatter, on 18 February 2008.[40] However, the president of the Royal Spanish Football Federation (RFEF), Angel Villar, announced in July 2008 that it was Spain's intention to submit an individual World Cup bid, and that positive contacts had already taken place with the government, through the secretary of sports, Jaime Lissavetzky. No specifications were made then regarding a joint bid with Portugal.[41] On 23 November 2008, after his re-election for the RFEF presidency, Villar pledged that one of the fundamental objectives of his term was to bring a World Cup to Spain. While he did not mention whether Spain would present a joint bid with Portugal, he did not rule it out when asked about it.[42]

On 23 December 2008, Angel Villar restated "We need to present a strong, consistent and winning bid for the 2018 World Cup." He further confessed "Personally, I think it should be with Portugal."[43] Subsequently, in the aftermath of a RFEF meeting board, Spain and Portugal announced their intention to bid together.[44] Spanish sports newspaper Marca advanced some details about the potential bid: Spain would lead a twelve-stadium project with eight of the venues, and the opening and final games would be held in Lisbon and Madrid, respectively.[45] Spain has previously hosted the 1982 World Cup, while Portugal organised the Euro 2004.

Russia

[edit]Russia announced its intent to bid in early 2009, and submitted its request to FIFA in time.[46] The bid committee also included RFU CEO Alexey Sorokin and Alexander Djordjadze as the Director of Bid Planning and Operations.[47]

Fourteen cities were included in the proposal, which divided them into five different clusters: one in the north, centered on Saint Petersburg, a central cluster, centered on Moscow, a southern cluster, centered on Sochi, and the Volga River cluster. Only one city beyond the Ural Mountains was cited, Yekaterinburg. The other cities were: Kaliningrad in the north cluster, Rostov-on-Don and Krasnodar in the south cluster and Yaroslavl, Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, Saransk, Samara and Volgograd in the Volga River cluster.[48] At the time of bidding, Russia did not have a stadium with 80,000 capacity, but the bid called for the expansion of Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, already a UEFA Elite stadium, from a capacity of slightly over 78,000 to over 89,000. Russia hoped to have five stadiums fit to host World Cup matches ready by 2013 – two in Moscow and one stadium each in Saint Petersburg, Kazan and Sochi, which at the time was due to host the 2014 Winter Olympics.[49]

2022 bids

[edit]Australia

[edit]In September 2007, the Football Federation Australia confirmed that Australia would bid for the 2018 World Cup finals.[50] Previously, in late May 2006, the Victorian sports minister, Justin Madden, said that he wanted his state to drive a bid to stage the 2018 World Cup. Frank Lowy, the FFA chairman, stated that they aimed to use 16 stadiums for the bid.[51] Then Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced the Federal Government's support for the bid,[52] and in December 2008, Federal minister for sport Kate Ellis announced that the federal government would give the FFA $45.6 million to fund its World Cup bid preparation.[53] Rudd met with Sepp Blatter to discuss the Commonwealth Government's support of the bid in Zürich in July 2009.[54]

At the 2008 FIFA Congress, held in Sydney, FIFA president Sepp Blatter suggested that Australia concentrate on hosting the 2022 tournament,[55] but Lowy responded by recommitting Australia to its 2018 bid.[56] However, Australia ultimately withdrew from the bidding for the 2018 FIFA World Cup in favour of the 2022 FIFA World Cup on 10 June 2010, following comments from the chief of the Asian Football Confederation that the 2018 tournament should be held in Europe.[57][58]

Australia's largest stadiums are currently used by other major Australian sports whose domestic seasons overlap with the World Cup. The Australian Football League and National Rugby League claimed that loss of access to these major venues for eight weeks would severely disrupt their seasons and impact the viability of their clubs.[59][60] The AFL in particular had previously advised it would not relinquish Etihad Stadium in Melbourne for the entire period required.[61] On 9 May 2010 the AFL, NRL, and FFA announced a Memorandum of Understanding guaranteeing that the AFL and NRL seasons would continue, should the bid be successful. Compensation for the rival football codes would be awarded as a result of any disruptions caused by hosting the World Cup.[62] AFL CEO Andrew Demetriou came out in support of the bid, despite initially not supporting the bid.[63][64] Franz Beckenbauer indicated that the issue of factional disputes between the FFA, NRL and, AFL were not considered by the FIFA Executive Committee.[65] Although initially Australia seemed to be a popular contender to host the tournament, the final Australian World Cup bid received only one vote astonishing Franz Beckenbauer[66] and experts alike.

Japan

[edit]Japan bid to become the first Asian country to host the World Cup twice; however, the fact that they were co-hosts so recently in 2002 was expected to work against them in their bid.[67] Although Japan did not have an 80,000-seat capacity stadium, its plan was based on a proposed 100,000-seat stadium that would have gone on to be a centrepiece of 2016 Olympics, for which Tokyo was bidding.

Japan also pledged that if it had been granted the rights to host the 2022 World Cup games, it would develop technology enabling it to provide a live international telecast of the event in 3D, which would allow 400 stadiums in 208 countries to provide 360 million people with real-time 3D coverage of the games projected on giant screens, captured in 360 degrees by 200 HD cameras. Furthermore, Japan will broadcast the games in holographic format if the technology to do so is available by that time. Beyond allowing the world's spectators to view the games on flat screens projecting 3D imaging, holographic projection would project the games onto stadium fields, creating a greater illusion of actually being in the presence of the players. Microphones embedded below the playing surface would record all sounds, such as ball kicks, in order to add to the sense of realism.

The Olympic bid was unsuccessful, coming third in the bidding process that concluded in October 2009. The vice-president of the Japan Football Association, Junji Ogura, had previously admitted that if Tokyo were to fail in its bid, its chances of hosting either the 2018 or 2022 World Cup would not be very good.[68] On 4 May 2010, Japan announced that it was withdrawing its bid for the 2018 tournament to focus on 2022, amidst rising speculation that the 2018 edition will be held in Europe.[69]

Qatar

[edit]Qatar made a bid for only the 2022 World Cup. Qatar was attempting to become the first Arab country to host the World Cup. Failed bids from other Arab countries include Morocco (1994, 1998, 2006 and 2010), Egypt and a Libya-Tunisia joint bid withdrew in the 2010 World Cup bidding process.[18] Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani, son of the former Emir of Qatar, was the chairman of the bid committee.[70] Qatar planned to promote the bid as an Arab unity bid and hoped to draw on support from the entire Arab world and were positioning this as an opportunity to bridge the gap between the Arab and Western worlds.[71] The bid launched an advertising campaign across the nation in November 2009.[72]

Some concerns with Qatar's bid deal with the extreme temperatures.[73] The World Cup is always held in the European off-season in June and July and during this period the average daytime high in most of Qatar is in excess of 40 °C (104 °F), with the average daily low temperatures not dropping below 30 °C (86 °F).[74] Sheikh Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, the 2022 Qatar bid chairman, responded saying "the event has to be organised in June or July. We will have to take the help of technology to counter the harsh weather. We have already set in motion the process. A stadium with controlled temperature is the answer to the problem. We have other plans up our sleeves as well."[75] The first five proposed stadiums are planned to employ cooling technology capable of reducing temperatures within the stadium by up to 20 degrees Celsius. Additionally, the upper tiers of the stadiums will be dis-assembled after the World Cup and donated to countries with less developed sports infrastructure.[73]

President of FIFA Sepp Blatter endorsed the idea of having a World Cup in the Middle East, saying in April 2010, "The Arabic world deserves a World Cup. They have 22 countries and have not had any opportunity to organise the tournament." Blatter also praised Qatar's progress, "When I was first in Qatar[76] there were 400,000 people here and now there are 1.6 million. In terms of infrastructure, when you are able to organise the Asian Games (in 2006) with more than 30 events for men and women, then that is not in question."[77] Qatar's bid to host the 2022 World Cup received a huge boost on 28 July 2010 when Asian Football Confederation (AFC) President Mohammed Bin Hammam threw his weight behind his country's campaign. Speaking in Singapore, Bin Hammam said: "I have one vote and, frankly speaking, I will vote for Qatar but if Qatar is not in the running I will vote for another Asian country."[78] Qatar has already hosted the AFC Asian Cup in 1988, FIFA U-20 World Cup 1995 and the 2011 AFC Asian Cup.

South Korea

[edit]South Korea bid only for the 2022 World Cup. They were bidding to become the first Asian country to host the World Cup twice; however, the fact that they were co-hosts so recently in 2002 was expected to work against them in their bid. Han Seung-joo, a former South Korean Minister of Foreign Affairs, was appointed as the Chairman of the Bidding Committee in August 2009.[79] He met with FIFA President Sepp Blatter in Zürich, Switzerland.[80] In January 2010, President Lee Myung-bak visited the headquarters of FIFA in Zürich, Switzerland to meet Sepp Blatter in support of the South Korean bid.

Although South Korea did not have an 80,000 capacity stadium, it planned to upgrade an existing venue to meet that capacity. There are three grounds which can seat over 60,000 people—Seoul Olympic Stadium, Seoul World Cup Stadium and Daegu Stadium. Another 70,000 seat stadium is scheduled to be built in Incheon as the main stadium for the 2014 Asian Games. Other venues meet hosting requirements as they were built for the 2002 World Cup.[18] The 12 cities selected to hold the finals were South Korea to win the bid were selected in March 2010 and were Busan, Cheonan, Daegu, Daejeon, Goyang, Gwangju, Incheon (2 venues), Jeonju, Seogwipo, Seoul (2 venues), Suwon and Ulsan.[81]

United States

[edit]U.S. Soccer first said in February 2007 that it would bid for the 2018 World Cup.[82] On 28 January 2009, U.S. Soccer then announced that it would submit bids for both the 2018 and 2022 Cups.[83] David Downs, president of Univision Sports, was executive director of the bid. Other committee members included president of U.S. Soccer Sunil Gulati, U.S. Soccer chief executive officer Dan Flynn, Major League Soccer Commissioner Don Garber, and Phil Murphy, the former national finance chairman for the Democratic National Committee.[84] The vice president of FIFA, Jack Warner, who is also the president of CONCACAF, originally said he would try to bring the World Cup back to the CONCACAF region.[85] However, Warner also stated that he preferred the USSF change their plans to make a bid for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[86]

In April 2009, the bid committee identified 70 stadiums in 50 communities as possible venues for the tournament, with 58 confirming their interest.[87] The list of stadiums was trimmed two months later to 45 in 37 cities,[88] and then in August 2009 to 32 stadiums in 27 cities.[89] In January 2010, 18 cities and 21 stadiums were selected for the final bid. The cities were Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston (Foxboro), Dallas, Denver, Houston, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Miami, Nashville, New York, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Diego, Seattle, Tampa, and Washington, D.C. The cities with multiple qualifying stadiums were Los Angeles, Seattle, Dallas and Washington. With several large American football stadiums, the 21 venues were to have an average capacity of 77,000; none seated fewer than 65,000. Seven of the stadiums seat at least 80,000.[90] Two proposed stadiums would be used by Major League Soccer during the summer.[citation needed]

In October 2010, the United States withdrew from the 2018 bid process, to focus solely on the 2022 competition.[91]

Cancelled bids

[edit]Two countries had to cancel bids for the 2018 or 2022 FIFA World Cups before individual evaluations began. Mexico cancelled its bid for both cups, while Indonesia was only bidding for the 2022 World Cup.

Indonesia

[edit]In January 2009 the Football Association of Indonesia (PSSI) confirmed their intention to bid for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, with government support.[92][93] In February 2009, PSSI launched the "Green World Cup Indonesia 2022" campaign.[94] This campaign included a $1 billion plan to upgrade supporting infrastructure beside stadiums to meet FIFA's requirements. The funds to construct stadiums were to come from regional governments.[95] Indonesia had previously made World Cup history when it became the first Asian nation to play in a World Cup, at the 1938 tournament in France under its colonial name of the Dutch East Indies.[96] Indonesia also had tournament hosting experience as the co-host of 2007 AFC Asian Cup.

In the campaign presentation, PSSI president Nurdin Halid said he believed Indonesia stood a chance to win FIFA's approval to host the 2022 World Cup, despite the relatively poor infrastructure, coupled with the low quality of the national squad compared to other candidates. He said Indonesia had proposed a "Green World Cup 2022", hoping to capitalise on the current green and global warming movement worldwide: "Our deforestation rate has contributed much to world pollution. By hosting the World Cup, we wish to build infrastructure and facilities that are environmentally friendly so we can give more to the planet."[94]

The bid was launched at a moment when there were strong pressures from Indonesian football fans for Halid to step down from his position as chairman of PSSI. There was no official support from the government of Indonesia until 9 February 2010, the deadline for the country's government to file a letter of support for the bid.[97] Secretary General of PSSI Nugraha Besoes did not deny that Indonesia could be disqualified from the bidding process because the Indonesian government did not support the bid.[98] On 19 March 2010, FIFA rejected Indonesia's bid to host the 2022 World Cup because the government stated that their concern is for the people of the country and so could not support the bid as FIFA requested.[8] As a consequence, PSSI threw their support behind Australia's bid for the 2022 tournament.[99]

Mexico

[edit]Former Mexican Football Federation President, Alberto de la Torre, announced their intention to bid for the cup in 2005, but was ineligible because of the rotation policy at that time.[citation needed]

Selection

[edit]Eligible voters

[edit]- FIFA President

Sepp Blatter (banned in 2015 for eight years by FIFA Ethics Committee, amid a sweeping corruption investigation led by the U.S. in the 2015 FIFA corruption case)

Sepp Blatter (banned in 2015 for eight years by FIFA Ethics Committee, amid a sweeping corruption investigation led by the U.S. in the 2015 FIFA corruption case)

- Senior Vice President

Julio Grondona (died on 30 July 2014; indicted on 6 April 2020 by the U.S. Department of Justice)

Julio Grondona (died on 30 July 2014; indicted on 6 April 2020 by the U.S. Department of Justice)

- Vice Presidents

Issa Hayatou

Issa Hayatou Chung Mong-joon

Chung Mong-joon Jack Warner (indicted for corruption in 2015 FIFA corruption case)

Jack Warner (indicted for corruption in 2015 FIFA corruption case) Angel Maria Villar

Angel Maria Villar Michel Platini (banned in 2015 for eight years by the European Court of Human Rights for ethics violations, later reduced to four years)

Michel Platini (banned in 2015 for eight years by the European Court of Human Rights for ethics violations, later reduced to four years) Geoff Thompson

Geoff Thompson

- Members

Michel D'Hooghe

Michel D'Hooghe Ricardo Teixeira (indicted on 3 December 2015 by the U.S. Department of Justice)

Ricardo Teixeira (indicted on 3 December 2015 by the U.S. Department of Justice) Mohamed Bin Hammam (banned in 2011 for life from all football activities for ethics violations)

Mohamed Bin Hammam (banned in 2011 for life from all football activities for ethics violations) Şenes Erzik

Şenes Erzik Chuck Blazer (plead guilty to corruption charges in 2015 FIFA corruption case)

Chuck Blazer (plead guilty to corruption charges in 2015 FIFA corruption case) Worawi Makudi (banned in 2015 for five years for forgery and falsification)

Worawi Makudi (banned in 2015 for five years for forgery and falsification) Nicolas Leoz (indicted for corruption in 2015 FIFA corruption case)

Nicolas Leoz (indicted for corruption in 2015 FIFA corruption case) Junji Ogura

Junji Ogura Marios Lefkaritis

Marios Lefkaritis Jacques Anouma

Jacques Anouma Franz Beckenbauer

Franz Beckenbauer Rafael Salguero (indicted on 3 December 2015 by the U.S. Department of Justice)

Rafael Salguero (indicted on 3 December 2015 by the U.S. Department of Justice) Hany Abo Rida

Hany Abo Rida Vitaly Mutko

Vitaly Mutko

- Prevented from voting

Voting rounds

[edit]

On 2 December 2010, FIFA president Sepp Blatter announced the winning bids at FIFA's headquarters in Zürich. Russia was chosen to host the 2018 World Cup, and Qatar was chosen to host the 2022 World Cup.[101] This made Russia the first Eastern European country to host the World Cup, while Qatar would be the first Middle Eastern country to host the World Cup.[102][103] Blatter noted that the committee had decided to "go to new lands" and reflected a desire to "develop football" by bringing it to more countries.[104]

In each round a majority of twelve votes was needed. If no bid received 12 votes in a round, the bid with the fewest votes in that round was eliminated, and accordingly each remaining bid should receive no fewer votes in subsequent rounds than in preceding rounds. Multiple bids received fewer votes in voting round 2 compared to voting round 1 (Netherlands/Belgium, Qatar and Japan), at least 2 voting members in each of the 2018 and 2022 votes changed their votes between voting rounds despite their initial bid not being eliminated in voting round 1. The actual votes cast were as follows:[105]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Allegations of vote-buying

[edit]Shortly after the voting in December 2010, ESPN published allegations linking Qatar's successful bid to Football Dreams, a youth development program that channeled money from the Qatari government to football programs in 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia—six of which had representatives on the FIFA executive committee.[106] In February 2011, Blatter admitted that the Spanish and Qatari bid teams did try to trade votes, "but it didn't work".[107]

In May 2011, the former England 2018 bid chief Lord Treisman told a House of Commons select committee that four FIFA committee members approached him asking for various things in exchange for votes. Among the accused were FIFA Vice President Jack Warner, who allegedly asked for £2.5 million to be used for projects, and Nicolás Leoz, who allegedly asked to be knighted.[108] The Sunday Times further reported that month that Issa Hayatou and Jacques Anouma were given $1.5 million in exchange for their votes in favor of Qatar.[109] On 30 May 2011, FIFA President Sepp Blatter rejected the evidence in a press conference, while Jack Warner, who had been suspended that day for a separate ethics violations pending an investigation, leaked an email from FIFA General Secretary Jérôme Valcke which suggested that Qatar had "bought" the rights to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Valcke subsequently issued a statement denying he had suggested it was bribery, saying instead that the country had "used its financial muscle to lobby for support". Qatar officials denied any impropriety.[110] Theo Zwanziger, President of the German Football Association, also called on FIFA to re-examine the awarding of the Cup to Qatar.[111]

In July 2012, FIFA appointed former U.S. Attorney Michael J. Garcia to investigate allegations of vote-buying in the selection process. He submitted the report in September 2014, which FIFA at the time declined to release in full. Instead, FIFA released a summary that Garcia described as "materially incomplete," leading Garcia to resign in protest. FIFA ultimately published the report in 2017, after German tabloid Bild announced they would publish a leaked copy. The report detailed dozens of allegations but didn't provide hard evidence for vote-buying.[112] In May 2015, as members gathered in Zürich for the 65th FIFA Congress, U.S. federal prosecutors disclosed cases of corruption leading to the arrest of seven. More than 40 individuals were indicted, including 2018 and 2022 voters Luis Bedoya, Chuck Blazer, Nicolás Leoz, Rafael Salguero, Ricardo Teixeira, and Jack Warner.[113] The resulting cases led FIFA to suspend many members, including Issa Hayatou, and the end of Sepp Blatter's presidency of the organization.[114]

In April 2020, the United States Department of Justice unsealed further indictments against voters Nicolás Leoz, Ricardo Teixeira, Julio Grondona of Argentina, and Jack Warner. The indictments spelled out how shell corporations and sham consulting contracts were used to pay voters between $1–5 million for their support. Other voters who had previously pleaded guilty to accepting bribes, including Rafael Salguero of Guatemala, aided in the indictments, which when included with previous cases, mean that more than half of the voters were accused of wrongdoing related to their votes.[115] Voter Franz Beckenbauer has also been accused by Swiss prosecutors of embezzlement and money laundering related to voting in the 2006 FIFA World Cup host selection,[116] while Ángel María Villar was arrested in July 2017 for embezzlement, after previously being fined for failure to cooperate with investigations into vote-buying in the 2018 and 2022 host selection.[117]

Reactions

[edit]

In reaction to the announcement there were celebrations on the streets of Russia and Qatar.[118][119][120] The Qatar Stock Exchange responded strongly with increased participation in trading following the announcement.[121]

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad told his Qatari counterpart that hosting the tournament "is a big athletic event which can promote football in the Persian Gulf area and Middle East region." He also said Iran was ready to help Qatar in hosting the event, while saying he hoped its neighbours "could achieve a reasonable share to attend the games." al-Thani "underlined [a] necessity of cooperation between regional countries to use and take advantage of the sport opportunity." He also added that Qatar's initiative would motivate its neighbours to "promote and develop their football."[122]

Roger Burden, who had been acting chairman of England's Football Association, withdrew his application for the permanent post days after the vote, saying he could not trust FIFA members due to their actions.[123] England's bid executive Andy Anson said "I think it has to [change] because otherwise why would Australia, the United States, Holland, Belgium, England ever bother bidding again?"[124]

There was also a backlash from the media in the losing countries; the majority of British newspapers alleged that the World Cup had been "sold" to Russia, and the Spanish El Mundo, Dutch Algemeen Dagblad, and the Japanese Nikkei made comments about the financial power of Russia and Qatar's commodity and energy reserves.[125] American newspapers the Seattle Times and Wall Street Journal alleged collusion and corruption.

References

[edit]- ^ "Fifa abandons World Cup rotation". BBC News. 29 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ "New rotation proposal". BBC Sport. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ Hall, Matthew (18 September 2005). "Australia can host World Cup". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ "England withdraw bid for 2022 Cup". 15 October 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ Middleton, Dave (15 October 2010). "Europe certain to host 2018 World Cup as US withdraws from running". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Russia, Qatar win race to host World Cups as FIFA spreads its vision". CNN. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ "FIFA receives bidding documents for 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups" (Press release). FIFA.com. 14 May 2010. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Indonesia's bid to host the 2022 World Cup bid ends". BBC Sport. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 March 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ Dunbar, Graham (3 December 2009). "Bid teams focus on 2018, 2022 WCup hosting prize". USA Today. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ "Rotation ends in 2018". FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Egypt deny bid for 2022 World Cup". BBC News. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ "Benelux trio to apply to host 2018 World Cup". ESPN. 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ "Benelux countries launch 2018 World Cup bid". ESPN. 27 June 2007. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ "Benelux countries want World Cup". BBC News. London. 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Twelve nations bid for World Cup". BBC News. London. 3 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009.

- ^ "Associations of Belgium and the Netherlands officially announce interest in submitting joint bid". 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Ons dossier maakte indruk bij Platini". sporza.be (in Dutch). 19 March 2008. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Vesty, Marc (17 March 2009). "The race to host World Cup 2018 and 2022". BBC Sport. London. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ "België krijgt zeven speelsteden op het WK 2018". Sporza.be (in Dutch). Eindhoven. Belga. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ "World Cup 2018". September 2010. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Bennett, Rosemary (31 October 2007). "FA confirms 2018 World Cup Bid". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ "England plans its 2018 World Cup bid". Yahoo!. Associated Press. 24 April 2008. Archived from the original on 12 September 2019. Retrieved 29 April 2008.

- ^ "England submit 2018 World Cup bid". BBC Sport. London. 27 January 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ "Caborn to spearhead World Cup bid". BBC Sport. London. 28 June 2007. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Board confirmed for 2018". The Football Association. 24 October 2008. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Pearce, Edward (16 May 2010). "Geoff Thompson Replaces Lord Triesman As England 2018 Bid Chief". Goal.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Government launches work on 2018 bid". HM Treasury (press release). 18 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ "World Cup bid latest". Football Association. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- ^ Whittle, Mark (21 March 2006). "Heroes of '66 reunited". Football Association. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ "The World Cup and Economics 2006" (PDF). Goldman Sachs research report. 3 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ Kirkup, James (13 February 2007). "Chancellor's World Cup fever fails to grip the Scots". The Scotsman. Edinburgh, UK. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Milton Keynes part of England's 2018 World Cup bid". BBC Sport. 6 December 2009. Archived from the original on 17 December 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ "FIFA gives England hope". BBC News. London. 23 May 2004. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2007.

- ^ "Beckenbauer will back England bid". BBC Sport. London. 28 January 2007. Archived from the original on 14 February 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ "England gets Beckenbauer backing". BBC Sport. 29 July 2007. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Blatter Welcomes England Cup Bid". BBC Sport. 2 September 2005. Archived from the original on 1 December 2005. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ^ Scott, Matt (23 October 2007). "Prime minister to back 2018 World Cup bid in talks with Sepp Blatter". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Bond, David (27 November 2007). "Portugal and Spain to Launch Rival 2018 Bid". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Iberian threat to England's 2018 World Cup bid". ESPN. 27 November 2007. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ Brotons, Pablo (18 February 2008). "España y Portugal se unen para pedir el Mundial de 2018". Marca (in Spanish). Madrid. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "Villar confirma contactos con Lissavetzky para organizar el Mundial 2018". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. 16 July 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "Spain-Portugal Confirm 2018 World Cup Bid". Goal. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- ^ "Spain eyes joint 2018 World Cup bid with Portugal". International Herald Tribune. Paris. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ "La RFEF concreta su candidatura conjunta al Mundial 2018". Marca (in Spanish). Madrid. 23 December 2008. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ "Candidatura ibérica ao Mundial 2018 prevê abertura em Lisboa e final em Madrid". Público (in Portuguese). Lisbon. 20 December 2008. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ "Russia enters race to host 2018". BBC Sport. 20 January 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Bid committee". Russia 2018–2022 Bid. October 2009. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Host cities". Russia 2018–2022 Bid. October 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Russia ready to spend $10 bln on World Cup 2018 preparations". April 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Socceroos' stars coming home for two matches". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 21 September 2007. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Smithies, Tom (23 February 2008). "Lowy's vision for soccer". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ Gilmore, Heath; Proszenko, Adrian (28 February 2008). "PM makes the perfect pitch for World Cup". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ^ "$45m for 2018 World Cup bid". Sydney. AAP. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- ^ Australian Bid Page Archived 20 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Joint decision on 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups". FIFA. 30 May 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ "FFA to press on with 2018 Cup bid: Lowy". ABC News. AFP. 21 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ "World Cup 2010: Australia pull out of World Cup 2018 bidding". The Daily Telegraph. London. 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "World Cup 2018 should be in Europe, says Asian Football Confederation". The Guardian. London. 10 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ "AFL concerns over world cup run deep". ABC. 14 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ "Soccer's plan to displace NRL". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ "Cup bid needs to share the vision". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 December 2009. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009.

- ^ Walter, Brad (10 May 2010). "Rival codes finally shake hands on deal to play through World Cup". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ Heenan, Tom (3 March 2014). "Not every AFL point was a goal". The Age. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018.

- ^ Demetriou, Andrew (26 November 2010). "World Cup soccer 2022 debate". Herald Sun. Australia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Davutovic, David (28 November 2010). "Argy-bargy no threat to World Cup bid". Herald Sun. Australia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Beckenbauer astonished by Australia snub". www.abc.net.au. 4 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014.

- ^ "The race to host World Cup 2018 and 2022". BBC Sport. London. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009.

- ^ Himmer, Alastair (22 January 2009). "Japan World Cup bid rests on 2016 Olympic vote". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Japan drops bid to host 2018 World Cup to aim for 2022". BBC Sport. London. 3 May 2010. Archived from the original on 6 May 2010.

- ^ "Qatar 2022 announces Bid Committee leadership". Dubai Chronicle. 25 March 2009. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009.

- ^ "Qatar launch "unity" bid to stage 2022 World Cup finals". ESPN. 17 May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup Bid TV Commercial". YouTube. 15 November 2009.

- ^ a b Heathcote, Neil (4 May 2010). "Qatar pitches cool World Cup bid". BBC World News. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for Doha, Qatar". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ Tripathi, Raajiv; Nag, Arindam (25 March 2009). "Qatar will be great host for WC 2022". Qatar Tribune. Doha. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009.

- ^ Davies Krish (9 April 2019). "Qatar Worldcup 2022 Stadiums". OnlineQatar.

- ^ "Blatter reaches out to Arabia". Al Jazeera. 25 April 2010. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Bin Hammam talks up Qatar's 2022 bid". Sports Features Communications. 28 July 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ "Han Sung-Joo Appointed as the Chairman of the Bidding Committee". Korea Football Association. 20 August 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ (인터뷰) 한승주 위원장 "국제 축구계, 2022 월드컵 유치 의사 환영. Yahoo! News Korea (in Korean). 26 September 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Korea 2022 Reveals Host Cities" (Press release). World Football Insider. 4 March 2010. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ Goff, Steven (20 February 2007). "U.S. to Seek World Cup". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ "U.S. to bid for 2018 and 2022 World Cups". ESPNsoccernet. Chicago. Associated Press. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ^ Goff, Steve (2 February 2009). "USA in '18 (or '22)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ "Caborn hits back at Warner attack". BBC Sport. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ "Warner wants U.S. to bid for 2022 World Cup". Fox Sports (USA). Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ "2018 OR 2022 FIFA World Cup Bid Committee Contacts 70 US Venues". USA Soccer. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "USA Bid Committee Issues Requests For Proposals to 37 Potential FIFA World Cup Host Cities For 2018 or 2022" (Press release). United States Soccer Federation. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "USA Bid Committee Announces List of 27 Cities Still in Contention For Inclusion in U.S. Bid to Host FIFA World Cup in 2018 or 2022" (Press release). United States Soccer Federation. 20 August 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "Bid Committee announces official bid cities" (Press release). The USA Bid Committee. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "US withdraw bid to host 2018 World Cup". BBC Sport (Press release). 15 October 2010. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive: Indonesia – Hosting World Cup Is Not Impossible". Goal.com. 30 January 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Full Support from government for WC bid". detik.com. 29 January 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ a b Hotland, Tony (11 February 2009). "Indonesia upbeat to host 'green' World Cup". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "10,000 million rupiahs for stadia constructions". vivanews.com. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ^ "Indonesia joins race to host 2018, 2022 World Cup". The Jakarta Post. Associated Press. 28 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ "Indonesia's bid for 2022 World Cup in question". Sports Illustrated. 9 February 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Indonesia Dicoret, Selamat Tinggal Piala Dunia". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Indonesia backs Australia's 2022 FIFA World Cup Bid". Australia 2022 FIFA World Cup bid. 12 June 2010. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ a b Fylan, Kevin (1 December 2010). "Q+A - Voting for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup hosts". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Russia and Qatar awarded 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups". FIFA.com. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Gibson, Owen (2 December 2010). "England beaten as Russia win 2018 World Cup bid". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Jackson, Jamie (2 December 2010). "Qatar win 2022 World Cup bid". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Longman, Jeré (2 December 2010). "Russia and Qatar Win World Cup Bids". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ "Russia and Qatar to host 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cups, respectively". FIFA. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Latham, Brent (21 December 2010). "Behind Qatar's football success". ESPN. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ "Sepp Blatter hints at 2022 summer World Cup in Qatar". BBC Sport. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

I'll be honest, there was a bundle of votes between Spain and Qatar. But it was a nonsense. It was there but it didn't work, not for one and not for the other side.

- ^ "Triesman accuses four FIFA members". ESPN Soccernet. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ "FIFA demands evidence of corruption". ESPN Soccernet. 11 May 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Doherty, Regan E. (30 May 2011). "Qataris brush off allegations of buying World Cup rights". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ "German Federation asks Fifa for inquiry into Qatar 2022". BBC Sport. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Keh, Andrew (27 June 2017). "In Long-Secret FIFA Report, More Details but No Smoking Gun". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "The Soccer Officials Indicted on Corruption Charges". The New York Times. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Borden, Sam; Schmidt, Michael S.; Apuzzo, Matt (2 June 2015). "Sepp Blatter Decides to Resign as FIFA President in About-Face". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Indictment Reveals Details of Alleged Bribes for 2018, 2022 FIFA World Cup Votes". Sports Illustrated. Associated Press. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Franz Beckenbauer probe to be split from World Cup investigation". Deutsche Welle. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Ángel María Villar resigns from Uefa and Fifa positions after arrest in Spain". The Guardian. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Russia celebrates its selection as World Cup 2018 hosts | DW | 02.12.2010". DW.COM.

- ^ Al Jazeera English. 2 December 2010. 18:00 GMT.

- ^ "A World Cup miracle". BBC Sport. 2 December 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Hankir, Zahra; Namatalla, Ahmed (12 December 2010). "Egypt Shares Gain on View Central Bank May Cut Interest Rates, Led by CIBE". Bloomberg.

- ^ http://cms.mfa.gov.ir/cms/cms/Tehran/en/Ifrem/1898912[permanent dead link]

- ^ BBC News, 4 December 2010.

- ^ 'Why bother': Australia warned against future Cup bids Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Rachael Brown, ABC News, 4 December 2010

- ^ "English media angry at Fifa 'fix'". BBC News. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.