24 Hour Revenge Therapy

| 24 Hour Revenge Therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | February 7, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | May and August 1993 | |||

| Studio | Steve Albini's house, Chicago, Illinois; Brilliant, San Francisco, California | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 37:11 | |||

| Label |

| |||

| Producer | Jawbreaker | |||

| Jawbreaker chronology | ||||

| ||||

24 Hour Revenge Therapy is the third studio album by American punk rock band Jawbreaker, released on February 7, 1994, through Tupelo Recording Company and Communion Label. Before the release of their second studio album Bivouac (1992), frontman Blake Schwarzenbach developed a polyp on his vocal chords. While on tour in Europe, he went to a hospital; upon returning to the United States, the band took up day jobs. Recording sessions for their next album were held at Steve Albini's house in Chicago, Illinois across three days in May 1993. While on tour, they listened to tapes they made of the sessions; Schwarzenbach was unhappy with the recordings. Three songs were subsequently recorded in a single day at Brilliant in San Francisco, California in August 1993 with Billy Anderson.

24 Hour Revenge Therapy received generally favourable reviews from music critics, some of whom praised the songwriting. Described as a blend of their traditional punk rock and pop-punk sound, it harkened back to the simplistic arrangements of Jawbreaker's debut studio album Unfun (1990). They supported Nirvana on their US tour, which earned them backlash from members of the punk community, and then went on a stint with J Church, prior to the release of the album. They supported it with a seven-week US trek, a West Coast tour with Jawbox, and a stint in Europe at the end of 1994. 24 Hour Revenge Therapy has been included on best-of lists for pop-punk and emo by the likes of Alternative Press and Rock Sound; Chris Conley of Saves the Day and Rise Against had expressed admiration for the album.

Background and writing

[edit]While Jawbreaker was touring across the United States, frontman Blake Schwarzenbach had developed a polyp on his vocal chords. They had planned to get their roadie Raul Reyes to sing for the remainder of the trek. After a single show where Reyes could not recall the lyrics, Schwarzenbach started singing again. The band then embarked on a tour of Europe; during it, he would cough up blood.[1] As they were unable to fly home due to fog, Schwarzenbach went to a hospital in October 1992.[1][2] As he was recovering, the rest of the band spent time in London with Lookout! Records staff member Christy Colcord.[1] After leaving the hospital, Schwarzenbach was instructed not to talk or drink for a period of five days. His first show post-surgery saw his vocals being altered two octaves higher.[1] A month prior to this, Schwarzenbach said that the band were eager to return to the studio to record, having written ten new songs. They had recorded their second album Bivouac a year ago, though it had yet to be released. Drummer Adam Pfahler explained that because a significant amount of time had elapsed since recording, many of the songs were no longer part of their live shows.[3] While they had performed nearly half of the material that would end up on their third album by October 1992,[4] Bivouac only saw release two months later.[5] It was a darker-sounding release that took inspiration from the Midwestern and Washington, D.C. post-punk scenes.[6]

After returning to the US, bassist Chris Bauermeister stayed at the band's residence on Sycamore Street in San Francisco, California, as Pfahler moved to Albion Street in Los Angeles, California, and Schwarzenbach moved to Oakland, California.[4] Bauermeister worked at a toy store, and Pfahler spent time running a video store, as Schwarzenbach wrote new material alone and served as a librarian. The members would meet up and hold practice sessions in the basement of a club.[1] The material that Schwarzenbach came up with revolved around locations, relationships and people; Ronen Givony, who wrote the 2018 33 1/3 book on the band, said that while the tracks on Bivouac were "figurative, the new songs were confessional, unguarded, [and] diaristic".[7] Bauermeister and Pfahler acknowledged that Bivouac was a collaborative effort between the three of them, which contrasted this new set of songs that were solely Schwarzenbach's creation.[8] Prior to recording their next album, they had all of the material for it fully planned out, and already had a sequence for it.[1] Gary Held of Revolver Distribution lent the band $2,000 to cover the cost of recording as well as food, lodging and gas.[9] They were prepared to the point where they performed what would be the album in order for Held.[10]

Production

[edit]

Jawbreaker began their van trip from San Francisco to engineer Steve Albini's house in Chicago, Illinois on May 14, 1993, arriving a few days later.[9] 24 Hour Revenge Therapy would be mainly recorded at Albini's residence across three days that same month.[1][11] Albini had built up a reputation as an engineer recording revered albums by the likes of Nirvana and PJ Harvey, alongside the works of acts that members of Jawbreaker admired, such as Big Black and the Jesus Lizard.[12] Though he was not that familiar with the band, he was aware of them and considered them "one of the few punk bands [...] that had a more melodic sensibility".[13] Albini had upgraded the recording console at his house from eight-tracks to 24-tracks prior to this. As such, he recorded a large number of bands in a small time period in order to pay the bill for the equipment.[1] Upon arriving, Schwarzenbach remarked that the Jesus Lizard were practicing in Albini's basement; Jawbreaker moved all of their gear into that location, which was where they would be recording.[1][14] Pfahler said on the first day, Bauermeister and himself had started taping basic tracks at 3pm and were finished by 6pm.[13]

The day after, Schwarzenbach tracked his guitar lines and vocals; the next day, they began the mixing process. Two songs into the session, the tape machine became faulty and caught fire.[15] Any further work was halted without a working machine; another act was scheduled to work with Albini at the weekend.[16] A national tour was planned to begin after sessions wrapped, though the initial first show in Dayton, Ohio was cancelled as Jawbreaker remained in Chicago. While in town, they played a sold-out show at Isabele's Grand Finale on May 23 with Nuisance and Friction. [17] On 25 May 1993, they re-started mixing as the machine was fixed, working from 9AM to almost midnight.[18] Albini ultimately billed the band $1,032 for the three full days of recording and mixing. The next day, they went to the residence of Screeching Weasel frontman Ben Weasel and listened to the album. Pfahler later regretted doing this, stating that they were "too close to it. We had no distance [...] we didn't have it in our head right".[19] Schwarzenbach said: "There's always that point where you can really freak yourself out, and we did". They then embarked on the When It Pains It Roars tour through to July 1993.[20] After 30 shows, they eventually re-listened to the tapes, which Schwarzenbach were not satisfied with.[1][20]

After the tour concluded, they spent a day with Billy Anderson, tracking at Brilliant Studio in San Francisco, California.[11][20] The band self-produced the proceedings, while Anderson served as the engineer.[11] During this, "The Boat Dreams from the Hill" and "Boxcar" were re-recorded, "Do You Still Hate Me?" and "Jinx Removing" were re-mixed, and "Condition Oakland" was recorded.[21] "The Boat Dreams from the Hill" was re-done as the song did not have enough pauses in the music for Schwarzenbach to sing over.[1] In addition, the pick slide and lead guitar part that opens the track was swapped for Pfahler's drums.[22] "Boxcar" was also re-made, with an increase in tempo. They altered those songs based on live performances sometime prior.[1] Around this time, he wrote "Condition Oakland", which he felt was "a good summation" of recording music; as they had been playing it on tour, they opted to record it for their next album.[1][22] Making the track at Brilliant was "pretty perfect" due to the studio's large size, making it "kind of a cavernous song".[1] A sample of Jack Kerouac and Steve Allen was recorded for it by playing a cassette of performing, done by pointing a Shure SM57 microphone at a boom box speaker.[22] Pfahler said the session with Anderson cost $500.[23] As Albini preferred not to be credited, he was listed as the engineer Fluss in the album's booklet, which was the name of his cat.[1][19][24] He reasoned that as Jawbreaker composed and played "and made the decisions [... they're] doing all the work, I'm sort of part of the equipment". For the 20th anniversary version of the album, he is credited as doing the recording, while Fluss is still listed as the engineer.[19] John Golden mastered the album at K-Disc in Hollywood, California.[11]

Composition and lyrics

[edit]Overview

[edit]Musically, the sound of 24 Hour Revenge Therapy has been described as punk rock,[1][22][25][26] pop-punk,[25][27] and emo.[28] Dan Fidler of Spin said it was "composed of short, tight arrangements", centered around Pfahler's "furious drumming" and Bauermeister's "barreling bass".[29] The latter realised the "value of pulling back and not doing fills every chance I got, but trying to put them in useful places and places that made sense".[22] Schwarzenbach's vocals were compared to Paul Westerberg of the Replacements and Richard Butler of the Psychedelic Furs.[25] The material on the album were Schwarzenbach-written, instead of the more collaborative efforts on Bivouac.[1] The latter album saw the band lean towards a more progressive sound, while 24 Hour Revenge Therapy had simplified arrangements, closer to their debut studio album Unfun (1990).[25]

Schwarzenbach highlighted five albums that he listened to while creating 24 Hour Revenge Therapy: Bad Moon Rising (1985) by Sonic Youth; World Outside (1991) by the Psychedelic Furs; No Pocky for Kitty (1991) by Superchunk; Something Vicious for Tomorrow (1992) by Treepeople; and The Problem with Me (1993) by Seam.[30] Schwarzenbach explained that 24 Hour Revenge Therapy dealt with a single relationship he experienced.[31] Givony wrote that the album largely details a story "familiar to every young person who moves to a new city, makes friends, falls in love, and reluctantly grows up"; the first three tracks fall out of this remit, as they are a "farewell to a [music] scene that had outlived its novelty, interest, or usefulness".[32] The lyrics avoided the literary vagueness of their previous releases in favor of directness.[33]

Lyrics

[edit]The album's lyrics have been compared to those of the Replacements.[34] The opening track to 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, "The Boat Dreams from the Hill", was inspired by Schwarzenbach seeing a boat on a hill while driving in Santa Cruz.[1] It switches viewpoints from the unfixable boat drifting on water, to a pensioner building the boat, and losing one's voice.[25][35] Givony said the boat was used as a metaphor for "potential – a container for 'every man's' wishes".[36] "Indictment" levies criticism towards major labels, and not caring about other peoples' opinions on songwriting.[24][37] Pfahler said the song's full title was "Scathing Indictment of the Pop Industry", tackling the process behind music distribution. Portions of his drum parts on it were influenced by Sugar and Dave Grohl of Nirvana.[22] "Boxcar" was written while on the side of a road in France, and deals with the concept of selling out in the punk rock scene.[1][35] "Outpatient" was written following Schwarzenbach's hospitalization; Pfahler thought it sounded similar to the tracks on Bivouac.[1][22] Schwarzenbach said it was a series of vignettes of his vocal surgery, though he had "about 10 memories or images to choose from because I was unconscious for a lot of it".[22]

"Ashtray Monument" sees Schwarzenbach discuss his parents' divorce, and his perspective in its aftermath.[35] He said it was about life in Mission District, San Francisco, specifically the band's apartment on Sycamore Street.[22] Deciphering the title, Givony wrote that an "ashtray monument is one that has been allowed to grow beyond recognition: an image of surrender, or extreme, unhealthy solitude".[38] It begins with an abrasive guitar part and several drum fills, which saw Pfahler emulating the style of Cheap Trick drummer Bun E. Carlos.[39] "Condition Oakland" tackles the theme of loneliness, as well as the difficulties of being an artist. The song was influenced by the music of Swervedriver and Treepeople being in frequent rotation for Schwarzenbach, in which he attempted to sing like the latter's frontman Doug Martsch.[1] It is in 3/4 time, and includes a sample of Kerouac reciting (with Allen playing piano) "October in the Rail Earth" from Lonesome Traveler.[1][22][40] "Ache" is a leftover from the Bivouac sessions; for 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, Schwarzenbach played an anthemic-sounding guitar running through a RadioShack amplifier.[1] Unlike the Bivouac version, the 24 Hour Revenge Therapy rendition uses vocal overdubs to enact a call-and-response section.[41] Givony said it dealt with "thinking things through, and not caring if you're being lied to, so long as those lies come with a veneer of intimacy".[42]

"Do You Still Hate Me?" is a love song about the aftermath of a relationship; its chorus consists of unanswered questions.[40] "West Bay Invitational" talks about a house party and existentialism.[40] Discussing the song, Pfahler said him and Schwarzenbach shared an apartment on the top floor, with Bauermeister, Reyes and Hahn in another apartment opposite them.[22] In early 1991, the band decided to throw a massive party with various people from bands and labels; Schwarzenbach said aspects of the event ended up in "West Bay Invitational".[22][43] A girl is referenced in the lyrics as being from Oakland, which she was actually from Arkansas.[23] She was a friend of Ben Sizemore of Econochrist, who previously toured with Jawbreaker in 1990.[23][44] "Jinx Removing" details a relationship at its end, while trying to compromise in holding it together.[35] Schwarzenbach felt disconnected from his girlfriend, despite them living 20 city blocks apart; Bauermeister said it shared a similar structure to "The Boat Dreams from the Hill".[22] Schwarzenbach said it was about the "Santeria cult in domestic American relationships".[45] The album's closing track, "In Sadding Around", was known as "New Slow Sad" during its initial live performances.[46] The final title comes from a Schwarzenbach's roommate Bob McDonald; Pfahler said that Schwarzenbach asked McDonald what had planned to do one say, to which McDonald responded that he would be "in sadding around all day".[47] Discussing the track, Pfahler said that "underneath it all there is this hope, that even with all of this devastation around, your narrator is still saying [positive] things".[22]

Release

[edit]While on the When It Pains It Roars tour, dubbed copies of 24 Hour Revenge Therapy had circulated among Jawbreaker's fans. Givony referred to this as an "uncommon early example of the pre-Internet album leak".[20] In October 1993, Schwarzenbach returned to his apartment in Oakland to find that one of his housemates, Bill Schneider, had taken a message and phone number for John Silva of Gold Mountain Management. After contacting the company, Silva offered Jawbreaker the opportunity to support Nirvana on tour.[48] It was the result of Cali DeWitt, who was babysitting Frances Bean Cobain for Nirvana's frontman Kurt Cobain. DeWitt had seen Jawbreaker a few times previously, and suggested them to Cobain when the Wipers had to drop out.[1] They subsequently appeared on the In Utero tour, playing to 3–6,000 people per night between October 19 and 26, 1993.[1][49] During the first date, the band had parked their van next to ten buses that were part of Nirvana's entourage. Pfahler said it was not a "rock-star moment. It was one of those, oh Jesus Christ, what have we gotten ourselves into?"[49] Though they received major backlash from members of the punk community for taking the support slot, the band did not regret the experience.[50] Jawbreaker then toured across the US with J Church; the San Francisco date erupted into a fight due to a heckler, which saw the police being called in.[24]

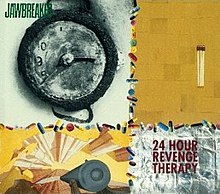

AllMusic states the release date of 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, which was done through Tupelo Recording Company and The Communion Label, to be February 7, 1994, while Givony gives the date of February 15, 1994.[51][52] He wrote that the artwork was a "study in contrasts: deadly serious and playfully lighthearted; vivid, realistic color next to minimalist abstraction". He went on to express that it summarizes the album's "contents: disaster and depression, but also persistence, stoicism, and humor; solitude and isolation".[53] The artwork is a collage of items which Pfahler created in his kitchen over the course of an afternoon; it consists of a grid of four squares. The top-left box is a black-and-white photograph of a pocket watch found in Hiroshima, Japan after an atomic bomb had impacted the city. The top-right square features three safety matches grouped together on top of unrolled cigarette filters.[54] The bottom-left box is an image of a cannon pointing down at a canyon, taken from a Looney Tunes Road Runner short.[54][55] The bottom-right square consists of foil from a cigarette packet; the album's title is included in maroon-colored letters, referencing the tips of the matches in the top-right box.[54] The squares are bordered by various tablets and pills taken from a drug almanac, such as paxil, prozac and zoloft.[56] Pfahler took black-and-white images that accompany each track in the booklet, including a stack of pennies for "Indictment", train tracks for "Boxcar" and candles for "Jinx Removing".[53]

24 Hour Revenge Therapy was quickly overshadowed by the popularity of Dookie (1994) by Green Day and Smash (1994) by the Offspring, both of which pushed pop-punk and punk rock into the mainstream.[26][57] In the aftermath of this, Jawbreaker started playing 500-capacity venues; they embarked on a seven-week US tour from March 1994.[58] Backlash continued to grow from readers of the punk zine Maximum Rocknroll and people in the East Bay region of San Francisco. The band were still being lambasted for touring with Nirvana, as well as for dropping the Unfun songs from their live repertoire and the change of voice from Schwarzenbach after his surgery.[59] It reached a point where, during one show, a member of the crowd frequently tried to spit in Schwarzenbach's mouth.[60] The June 1994 issue of Maximum Rocknroll was devoted to independent and major labels; Weasel spent part of his column in the zine defending the band.[61] Jawbreaker went on a short, ten-day tour on the US West Coast with Jawbox.[62] They closed out the year with a tour of Europe in November 1994.[63]

In October 2014, Pfahler's label Blackball Records issued 24 Hour Revenge Therapy. It featured alternative takes of "The Boat Dreams from the Hill", "Boxcar", "Do You Still Hate Me?" and "Jinx Removing", alongside two outtakes, "First Step" and "Friends Back East".[64] The latter two were previously included on the band's first compilation album Etc. (2002).[25] The alternative takes of "Boxcar" and "Do You Still Hate Me?" were made available for streaming through the band's website in the lead up to the reissue.[65] In addition to this, footage of Mission District from 1992 was compiled into a music video for "Boxcar", directed by Pfahler.[66][67] Blackball Records has since re-pressed it on vinyl in 2015, 2017, 2021 and 2022.[68]

Reception and legacy

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| Pitchfork | 9.1/10[25] |

24 Hour Revenge Therapy was met with generally positive reviews from music critics. Will Dandy of Punk Planet said Schwarzenbach's lyrics got "more confusing and metaphoric" with each release. Despite this, he called the music "pulsing, [...] with a spontaneous feel".[70] AllMusic reviewer Mike DaRonco found the band to "deal with their endeavors through music instead of wallowing in them, making this record not entirely bleak".[37] Pitchfork contributor Brandon Stosuy said that the album provided "some of the most indelible examples of punk music crammed with emotion. These are life-changing songs that, a couple decades later, still give goosebumps".[25] Louder writer Mischa Pearlman called it a "dark, late night cigarette of a record, one full of hope and despair and jaded existentialism".[26]

By the release of Givony's book in 2018, 24 Hour Revenge Therapy had sold 70,000 copies.[71] Joe Gross of Spin said that Bivouac and 24 Hour Revenge Therapy were "two of early emo's key documents".[28] Discussing its legacy, Givony wrote that it acted as a time capsule of a period before the "internet and email became ubiquitous [...] of the last moment when artists and fans genuinely cared whether a big corporation or a small indie label released their music".[72] Vagrant Records founder Rich Egan considers it his favorite album; Andy Greenwald, author of Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo (2003), wrote that Egan's "reasons read like a band-by-band blueprint" for the label's success in the early 2000s.[73] It has been included on best-of list for pop-punk by Rock Sound, and for emo by Alternative Press.[27][74] NME included "Jinx Removing" on their list of the ten best emo songs from the 1990s.[75] Rise Against cited the album as one of their 12 key influences, alongside works by Bad Religion, Dead Kennedys and Fugazi.[76] Josh Caterer of the Smoking Popes, Chris Conley of Saves the Day and Craig Finn of the Hold Steady have expressed admiration for the album.[1][77] Several of the songs have been covered for different tribute albums over the years: one for So Much for Letting Go: A Tribute to Jawbreaker Vol. 1 (2003);[78] five for Bad Scene, Everyone's Fault: Jawbreaker Tribute (2003);[79] and five for What's the Score? (2015).[80] Gordon Withers covered "The Boat Dreams from the Hill", "Boxcar", "Ashtray Monument" and "Ache" for his album Jawbreaker on Cello (2019), which came about from his involvement in the Jawbreaker documentary Don't Break Down (2017).[81][82]

| Publication | List | Rank | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA Weekly | Top 20 Emo Albums in History | 13 | |

| Rock Sound | The 51 Most Essential Pop Punk Albums of All Time | 34 | |

| Stereogum | The Top 20 Steve Albini-Recorded Albums | 7 |

Track listing

[edit]All songs by Blake Schwarzenbach.[11]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Boat Dreams from the Hill" | 2:39 |

| 2. | "Indictment" | 2:49 |

| 3. | "Boxcar" | 1:54 |

| 4. | "Outpatient" | 3:41 |

| 5. | "Ashtray Monument" | 3:04 |

| 6. | "Condition Oakland" | 5:17 |

| 7. | "Ache" | 4:14 |

| 8. | "Do You Still Hate Me?" | 2:52 |

| 9. | "West Bay Invitational" | 3:58 |

| 10. | "Jinx Removing" | 3:13 |

| 11. | "In Sadding Around" | 3:54 |

2014 reissue bonus tracks

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 12. | "The Boat Dreams from the Hill" (alternate take) | 2:42 |

| 13. | "Boxcar" (alternate take) | 2:00 |

| 14. | "Do You Still Hate Me" (alternate take) | 2:52 |

| 15. | "Jinx Removing" (alternate take) | 3:15 |

| 16. | "First Step" (outtake) | 3:26 |

| 17. | "Friends Back East" (outtake) | 2:15 |

Personnel

[edit]Personnel per booklet, except where noted.[11]

|

Jawbreaker

Additional personal

|

Production and design

|

See also

[edit]- In Utero – the 1993 album by Nirvana, which Albini recorded shortly before 24 Hour Revenge Therapy

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Galil, Leor (April 28, 2017). "The Definitive Oral History of Jawbreaker's 24 Hour Revenge Therapy". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 43

- ^ Bouffon, Le (May 1993). "Jawbreaker". Maximum Rocknroll (Interview) (120).

- ^ a b Givony 2020, p. 47

- ^ Thomas, Fred. "Bivouac - Jawbreaker | Release Info". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Kyle (November 28, 2006). "Jawbreaker: Bivouac". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 47, 48

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 48

- ^ a b Givony 2020, pp. 51–2

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 52

- ^ a b c d e f 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (booklet). Tupelo Recording Company/Communion Label. 1994. TUP 49-4/COMM 49-4.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 51

- ^ a b Givony 2020, p. 53

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 52–3

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 54

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 54–5

- ^ "Jawbreaker-Nuisance-Friction @ Chicago IL 5-23-93". Hardcore Show Flyers. November 18, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 55

- ^ a b c Givony 2020, p. 56

- ^ a b c d Givony 2020, p. 57

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 57–8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Pearlman, Mischa (February 6, 2019). "Decoding Jawbreaker's Monumental 24 Hour Revenge Therapy 25 Years On". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Kelley, Trevor (October 6, 2014). "'You could shoot a gun in the air and hit a great song'—Jawbreaker discuss '24 Hour Revenge Therapy'". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Jawbreaker Days of Whine and Poses". Exclaim!. March 26, 2010. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stosuy, Brandon (October 16, 2014). "Jawbreaker: 24 Hour Revenge Therapy". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c Pearlman, Mischa (October 9, 2014). "In Praise Of... Jawbreaker's 24 Hour Revenge Therapy". Louder. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bird, ed. 2014, p. 70

- ^ a b Gross 2004, p. 103

- ^ Fidler 1994, p. 22

- ^ "5 Records with Jawbreaker's Blake Schwarzenbach". Discogs. Archived from the original on February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Nonogirl; Squeaky (April 1996). "Jawbreaking with Blake Schwarzenbach" (Interview). No. 2. Static.

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 48, 61

- ^ Oh, Vivianne (1995–1996). "Jawbreaker". Alternative Press (Interview).

- ^ Earles, Andrew (September 15, 2014). Gimme Indie Rock: 500 Essential American Underground Rock Albums 1981-1996. Yoyageur Press. p. 161.

- ^ a b c d Nelson, Michael (November 30, 2012). "The 10 Best Jawbreaker Songs". Stereogum. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 61

- ^ a b c DaRonco, Mike. "24 Hour Revenge Therapy – Jawbreaker". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 73

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 73–4

- ^ a b c Pearlman, Mischa (July 2, 2015). "The 13 best songs by Jawbreaker". Louder. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 81

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 45

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 88

- ^ Stosuy, Brandon (January 9, 2013). "Jawbreaker: Bivouac". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 91

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 93

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 94

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 101, 130

- ^ a b Givony 2020, p. 103

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 108–9

- ^ DaRonco, Mike. "24 Hour Revenge Therapy - Jawbreaker | Release Info". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 119

- ^ a b Givony 2020, p. 97

- ^ a b c Givony 2020, p. 96

- ^ Bender, Alex (April 1999). "Interview with Adam Pfahler" (Interview). Loosecharm. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 96–7

- ^ Earles 2014, p. 159

- ^ Givony 2020, pp. 122–3, 128

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 130

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 131

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 135, 138

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 139

- ^ Ober, Autumn (November 1, 1994). "Jawbreaker – 24 Hour Revenge Therapy – Review". Lollipop Magazine. Archived from the original on September 6, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Adams, Gregory (July 10, 2014). "Jawbreaker Treat '24 Hour Revenge Therapy' to Expanded Reissue". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Jawbreaker launch new site for '24 Hour Revenge Therapy' reissue, stream alt. takes of 'Boxcar' & 'Do You Still Hate Me'". BrooklynVegan. October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on July 9, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Josiah (November 12, 2014). "Jawbreaker 'Boxcar' (video)". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Rettig, James (November 12, 2014). "Jawbreaker – 'Boxcar' Video". Stereogum. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Vinyl re-presses:

- 2015: 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (sleeve). Blackball Records. 2015. BB-010-LP.

- 2017: 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (sleeve). Blackball Records. 2017. BB-010-LP.

- 2021: 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (sleeve). Blackball Records. 2021. BB-010-LP.

- 2022: 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (sleeve). Blackball Records. 2022. BB-010-LP.

- ^ Prickett, Barry (1999). "Jawbreaker". MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. pp. 596–597 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Dandy 1994, p. 48

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 122

- ^ Givony 2020, p. 172

- ^ Greenwald 2003, p. 25

- ^ Makar, Bobby (March 10, 2020). "20 emo classics that helped define today's scene, from 1985 to 1997". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ Hughes, Mia (May 24, 2019). "10 best 90s emo songs: killer tracks from the genre's golden age". NME. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ^ Rise Against (October 7, 2008). "Rise Against's The 12 Albums That Changed The World". IGN. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Sacher, Andrew (October 21, 2019). "Saves The Day's Chris Conley discusses the music that influenced 'Through Being Cool'". BrooklynVegan. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ So Much for Letting Go: A Tribute to Jawbreaker Vol. 1 (booklet). Copter Crash Records. 2003. CC006.

- ^ Madsen, Nick (September 4, 2003). "Bad Scene, Everyone's Fault - Jawbreaker Tribute". IGN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ "What's the Score?". Save Your Generation Records. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via Bandcamp.

- ^ Pettigrew, Jason (August 16, 2019). "Jawbreaker song 'Bivouac' gets indiest cello rework you've ever heard". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Jawbreaker on Cello". Gordon Withers. Archived from the original on November 1, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2023 – via Bandcamp.

- ^ Whipple, Kelsey (October 10, 2013). "Top 20 Emo Albums in History: Complete List". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (January 26, 2012). "The Top 20 Steve Albini-Recorded Albums". Stereogum. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

Sources

- Bird, Ryan, ed. (September 2014). "The 51 Most Essential Pop Punk Albums of All Time". Rock Sound (191). ISSN 1465-0185.

- Dandy, Will (May–June 1994). "Record Reviews". Punk Planet (1).

- Earles, Andrew (2014). Gimme Indie Rock: 500 Essential American Underground Rock Albums 1981–1996. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760346488.

- Fidler, Daniel (April 1994). "Rock Candy". Spin. 10 (1). ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- Givony, Ronen (2020) [2018]. 24 Hour Revenge Therapy. 33 1/3. Vol. 130 (reprint ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-5013-2309-6.

- Greenwald, Andy (2003). Nothing Feels Good: Punk Rock, Teenagers, and Emo. New York City: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-30863-6.

- Gross, Joe (February 2004). "Emo Scene, Their Fault". Spin. 20 (2). ISSN 0886-3032. Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

External links

[edit]- 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (remastered) at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Video Rewind: A Trip Down Memory Lane with Jawbreaker’s “Do You Still Hate Me” at Consequence

- Punk in Silk Pajamas: Jawbreaker, Green Day And J-Church at Magnet

- 30 Years Later: Jawbreaker Cements Greatness With '24 Hour Revenge Therapy' at Glide Magazine