ASH1L

ASH1L (also called huASH1, ASH1, ASH1L1, ASH1-like, or KMT2H) is a histone-lysine N-methyltransferase enzyme encoded by the ASH1L gene located at chromosomal band 1q22. ASH1L is the human homolog of Drosophila Ash1 (absent, small, or homeotic-like).

Gene

[edit]Ash1 was discovered as a gene causing an imaginal disc mutant phenotype in Drosophila. Ash1 is a member of the trithorax-group (trxG) of proteins, a group of transcriptional activators that are involved in regulating Hox gene expression and body segment identity.[5] Drosophila Ash1 interacts with trithorax to regulate ultrabithorax expression.[6]

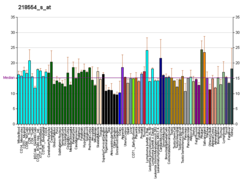

The human ASH1L gene spans 227.5 kb on chromosome 1, band q22. This region is rearranged in a variety of human cancers such as leukemia, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, and some solid tumors. The gene is expressed in multiple tissues, with highest levels in brain, kidney, and heart, as a 10.5-kb mRNA transcript.[7] Mutations in ASH1L in humans have been associated with autism, epilepsy, and intellectual disability.[8]

Structure

[edit]Human ASH1L protein is 2969 amino acids long with a molecular weight of 333 kDa.[9] ASH1L has an associated with SET domain (AWS), a SET domain, a post-set domain, a bromodomain, a bromo-adjacent homology domain, and a plant homeodomain finger (PHD finger). Human and Drosophila Ash1 share 66% and 77% similarity in their SET and PHD finger domains, respectively.[7] A bromodomain is not present in Drosophila Ash1.

The SET domain is responsible for ASH1L's histone methyltransferase (HMTase) activity. Unlike other proteins that contain a SET domain at their C terminus, ASH1L has a SET domain in the middle of the protein. The crystal structure of the human ASH1L catalytic domain, including the AWS, SET, and post-SET domains, has been solved to 2.9 angstrom resolution. The structure shows that the substrate binding pocket is blocked by a loop from the post-SET domain, and because mutation of the loop stimulates ASH1L HMTase activity, it was proposed that this loop serves a regulatory role.[10]

Protein expression patterns and timing

[edit]ASH1L is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body.[11][12][13][14] In the brain, ASH1L is expressed across brain areas and cell types, including excitatory and inhibitory neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia.[15][16][17] ASH1L also does not appear to show specificity to any brain region. In humans, ASH1L mRNA expression levels are fairly equal across all regions of cortex.[18][19] Similarly, in mice, ASH1L protein is highly expressed in the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, motor cortex, and basolateral amygdala.[20] In humans, ASH1L expression peaks prenatally and decreases after birth, with a second peak in expression towards adulthood.[18][19] In mouse, ASH1L is expressed in the developing central nervous system as early as embryonic day 8.5 [21][13] and is still expressed throughout the adult mouse brain.[22] Overall, the expression of ASH1L in the brain is spatially and temporally broad.

Function

[edit]The ASH1L protein is localized to intranuclear speckles and tight junctions, where it was hypothesized to function in adhesion-mediated signaling.[7] ChIP analysis demonstrated that ASH1L binds to the 5'-transcribed region of actively transcribed genes. The chromatin occupancy of ASH1L mirrors that of the TrxG-related H3K4-HMTase MLL1; however, ASH1L's association with chromatin can occur independently of MLL1. While ASH1L binds to the 5'-transcribed region of housekeeping genes, it is distributed across the entire transcribed region of Hox genes. ASH1L is required for maximal expression and H3K4 methylation of HOXA6 and HOXA10.[23]

A Hox promoter reporter construct in HeLa cells requires both MLL1 and ASH1L for activation, whereas MLL1 or ASH1L alone are not sufficient to activate transcription. The methyltransferase activity of ASH1L is not required for Hox gene activation but instead has repressive action. Knockdown of ASH1L in K562 cells causes up-regulation of the ε-globin gene and down-regulation of myelomonocytic markers GPIIb and GPIIIa, and knockdown of ASH1L in lineage marker-negative hematopoietic progenitor cells skews differentiation from myelomonocytic towards lymphoid or erythroid lineages. These results imply that ASH1L, like MLL1, facilitates myelomonocytic differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells.[5]

The in vivo target for ASH1L's HMTase activity has been a topic of some controversy. Blobel's group found that in vitro ASH1L methylates H3K4 peptides, and the distribution of ASH1L across transcribed genes resembles that of H3K4 levels.[23] In contrast, two other groups have found that ASH1L's HMTase activity is directed toward H3K36, using nucleosomes as substrate.[10][24]

Role in human disease

[edit]There are over 100 reported pathogenic, or disease-causing, variants in the ASH1L gene.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] About half of the variants arise de novo, and half are inherited. Of the inherited variants, about half are maternally inherited and half are paternally inherited. Disease-causing variants may be missense, nonsense, or frameshift mutations. The missense mutations are distributed throughout the gene body without localizing to a known functional domain of ASH1L.

All affected humans are heterozygous for ASH1L mutations. A single pathogenic copy of ASH1L causes disease, which may be the result of two different genetic mechanisms: haploinsufficiency or dominant negative function. The ClinGen clinical genomics resource states that there is “Sufficient Evidence for Haploinsufficiency” in ASH1L.[48]

The most common phenotypes, or symptoms, related to ASH1L mutations are autism spectrum disorder (ASD), epilepsy, intellectual disability, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) gives ASH1L a score of 1.1, indicating that ASH1L is a high confidence autism gene with the best level of evidence linking it to autism.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000116539 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000028053 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Tanaka Y, Kawahashi K, Katagiri Z, Nakayama Y, Mahajan M, Kioussis D (2011). "Dual function of histone H3 lysine 36 methyltransferase ASH1 in regulation of Hox gene expression". PLOS ONE. 6 (11): e28171. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...628171T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028171. PMC 3225378. PMID 22140534.

- ^ Rozovskaia T, Tillib S, Smith S, Sedkov Y, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Petruk S, et al. (September 1999). "Trithorax and ASH1 interact directly and associate with the trithorax group-responsive bxd region of the Ultrabithorax promoter". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 19 (9): 6441–6447. doi:10.1128/MCB.19.9.6441. PMC 84613. PMID 10454589.

- ^ a b c Nakamura T, Blechman J, Tada S, Rozovskaia T, Itoyama T, Bullrich F, et al. (June 2000). "huASH1 protein, a putative transcription factor encoded by a human homologue of the Drosophila ash1 gene, localizes to both nuclei and cell-cell tight junctions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (13): 7284–7289. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.7284N. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7284. PMC 16537. PMID 10860993.

- ^ a b "Gene: ASH1L -". Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "ASH1L_HUMAN". UniProt. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b An S, Yeo KJ, Jeon YH, Song JJ (March 2011). "Crystal structure of the human histone methyltransferase ASH1L catalytic domain and its implications for the regulatory mechanism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (10): 8369–8374. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.203380. PMC 3048721. PMID 21239497.

- ^ "ASH1L protein expression summary - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- ^ Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, et al. (January 2015). "Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. PMID 25613900.

- ^ a b Smith CM, Hayamizu TF, Finger JH, Bello SM, McCright IJ, Xu J, et al. (January 2019). "The mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): 2019 update". Nucleic Acids Research. 47 (D1): D774 – D779. doi:10.1093/nar/gky922. PMC 6324054. PMID 30335138.

- ^ Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Oksvold P, Kampf C, Djureinovic D, Odeberg J, et al. (February 2014). "Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 13 (2): 397–406. doi:10.1074/mcp.m113.035600. PMC 3916642. PMID 24309898.

- ^ Tasic B, Yao Z, Graybuck LT, Smith KA, Nguyen TN, Bertagnolli D, et al. (November 2018). "Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas". Nature. 563 (7729): 72–78. Bibcode:2018Natur.563...72T. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0654-5. PMC 6456269. PMID 30382198.

- ^ Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Caneda C, Plaza CA, Blumenthal PD, et al. (January 2016). "Purification and Characterization of Progenitor and Mature Human Astrocytes Reveals Transcriptional and Functional Differences with Mouse". Neuron. 89 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.013. PMC 4707064. PMID 26687838.

- ^ Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O'Keeffe S, et al. (September 2014). "An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex". The Journal of Neuroscience. 34 (36): 11929–11947. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. PMC 4152602. PMID 25186741.

- ^ a b Miller JA, Ding SL, Sunkin SM, Smith KA, Ng L, Szafer A, et al. (April 2014). "Transcriptional landscape of the prenatal human brain". Nature. 508 (7495): 199–206. Bibcode:2014Natur.508..199M. doi:10.1038/nature13185. PMC 4105188. PMID 24695229.

- ^ a b Cheon S, Culver AM, Bagnell AM, Ritchie FD, Vacharasin JM, McCord MM, et al. (April 2022). "Counteracting epigenetic mechanisms regulate the structural development of neuronal circuitry in human neurons". Molecular Psychiatry. 27 (4): 2291–2303. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01474-1. PMC 9133078. PMID 35210569.

- ^ Zhu T, Liang C, Li D, Tian M, Liu S, Gao G, Guan JS (May 2016). "Histone methyltransferase Ash1L mediates activity-dependent repression of neurexin-1α". Scientific Reports. 6: 26597. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626597Z. doi:10.1038/srep26597. PMC 4882582. PMID 27229316.

- ^ Elsen GE, Bedogni F, Hodge RD, Bammler TK, MacDonald JW, Lindtner S, et al. (2018). "The Epigenetic Factor Landscape of Developing Neocortex Is Regulated by Transcription Factors Pax6→ Tbr2→ Tbr1". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 571. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00571. PMC 6113890. PMID 30186101.

- ^ Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, et al. (January 2007). "Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain". Nature. 445 (7124): 168–176. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..168L. doi:10.1038/nature05453. PMID 17151600. S2CID 4421492.

- ^ a b Gregory GD, Vakoc CR, Rozovskaia T, Zheng X, Patel S, Nakamura T, et al. (December 2007). "Mammalian ASH1L is a histone methyltransferase that occupies the transcribed region of active genes". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 27 (24): 8466–8479. doi:10.1128/MCB.00993-07. PMC 2169421. PMID 17923682.

- ^ Tanaka Y, Katagiri Z, Kawahashi K, Kioussis D, Kitajima S (August 2007). "Trithorax-group protein ASH1 methylates histone H3 lysine 36". Gene. 397 (1–2): 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.027. PMID 17544230.

- ^ Faundes V, Newman WG, Bernardini L, Canham N, Clayton-Smith J, Dallapiccola B, et al. (January 2018). "Histone Lysine Methylases and Demethylases in the Landscape of Human Developmental Disorders". American Journal of Human Genetics. 102 (1): 175–187. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.11.013. PMC 5778085. PMID 29276005.

- ^ De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, et al. (November 2014). "Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism". Nature. 515 (7526): 209–215. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..209.. doi:10.1038/nature13772. PMC 4402723. PMID 25363760.

- ^ Grozeva D, Carss K, Spasic-Boskovic O, Tejada MI, Gecz J, Shaw M, et al. (December 2015). "Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis of 1,000 Individuals with Intellectual Disability". Human Mutation. 36 (12): 1197–1204. doi:10.1002/humu.22901. PMC 4833192. PMID 26350204.

- ^ Okamoto N, Miya F, Tsunoda T, Kato M, Saitoh S, Yamasaki M, et al. (June 2017). "Novel MCA/ID syndrome with ASH1L mutation". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 173 (6): 1644–1648. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38193. PMID 28394464. S2CID 9243148.

- ^ Shen W, Krautscheid P, Rutz AM, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Dugan SL (January 2019). "De novo loss-of-function variants of ASH1L are associated with an emergent neurodevelopmental disorder". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 62 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.003. PMID 29753921. S2CID 21674196.

- ^ Liu H, Liu DT, Lan S, Yang Y, Huang J, Huang J, Fang L (September 2021). "ASH1L mutation caused seizures and intellectual disability in twin sisters". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 91: 69–74. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2021.06.038. PMID 34373061. S2CID 235691774.

- ^ Tammimies K, Marshall CR, Walker S, Kaur G, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Lionel AC, et al. (September 2015). "Molecular Diagnostic Yield of Chromosomal Microarray Analysis and Whole-Exome Sequencing in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder". JAMA. 314 (9): 895–903. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.10078. PMID 26325558.

- ^ Homsy J, Zaidi S, Shen Y, Ware JS, Samocha KE, Karczewski KJ, et al. (December 2015). "De novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies". Science. 350 (6265): 1262–1266. Bibcode:2015Sci...350.1262H. doi:10.1126/science.aac9396. PMC 4890146. PMID 26785492.

- ^ Tang S, Addis L, Smith A, Topp SD, Pendziwiat M, Mei D, et al. (May 2020). "Phenotypic and genetic spectrum of epilepsy with myoclonic atonic seizures". Epilepsia. 61 (5): 995–1007. doi:10.1111/epi.16508. hdl:10067/1759860151162165141. PMID 32469098.

- ^ de Ligt J, Willemsen MH, van Bon BW, Kleefstra T, Yntema HG, Kroes T, et al. (November 2012). "Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (20): 1921–1929. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. PMID 23033978.

- ^ Wang T, Guo H, Xiong B, Stessman HA, Wu H, Coe BP, et al. (November 2016). "De novo genic mutations among a Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort". Nature Communications. 7: 13316. Bibcode:2016NatCo...713316W. doi:10.1038/ncomms13316. PMC 5105161. PMID 27824329.

- ^ Wang T, Hoekzema K, Vecchio D, Wu H, Sulovari A, Coe BP, et al. (October 2020). "Large-scale targeted sequencing identifies risk genes for neurodevelopmental disorders". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4932. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4932W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18723-y. PMC 7530681. PMID 33004838.

- ^ Iossifov I, O'Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, et al. (November 2014). "The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder". Nature. 515 (7526): 216–221. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..216I. doi:10.1038/nature13908. PMC 4313871. PMID 25363768.

- ^ Stessman HA, Xiong B, Coe BP, Wang T, Hoekzema K, Fenckova M, et al. (April 2017). "Targeted sequencing identifies 91 neurodevelopmental-disorder risk genes with autism and developmental-disability biases". Nature Genetics. 49 (4): 515–526. doi:10.1038/ng.3792. PMC 5374041. PMID 28191889.

- ^ Ruzzo EK, Pérez-Cano L, Jung JY, Wang LK, Kashef-Haghighi D, Hartl C, et al. (August 2019). "Inherited and De Novo Genetic Risk for Autism Impacts Shared Networks". Cell. 178 (4): 850–866.e26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.015. PMC 7102900. PMID 31398340.

- ^ Willsey AJ, Sanders SJ, Li M, Dong S, Tebbenkamp AT, Muhle RA, et al. (November 2013). "Coexpression networks implicate human midfetal deep cortical projection neurons in the pathogenesis of autism". Cell. 155 (5): 997–1007. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.020. PMC 3995413. PMID 24267886.

- ^ Guo H, Wang T, Wu H, Long M, Coe BP, Li H, et al. (2018). "Inherited and multiple de novo mutations in autism/developmental delay risk genes suggest a multifactorial model". Molecular Autism. 9: 64. doi:10.1186/s13229-018-0247-z. PMC 6293633. PMID 30564305.

- ^ Zhou X, Feliciano P, Shu C, Wang T, Astrovskaya I, Hall JB, et al. (September 2022). "Integrating de novo and inherited variants in 42,607 autism cases identifies mutations in new moderate-risk genes". Nature Genetics. 54 (9): 1305–1319. doi:10.1038/s41588-022-01148-2. PMC 9470534. PMID 35982159.

- ^ C Yuen RK, Merico D, Bookman M, L Howe J, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Patel RV, et al. (April 2017). "Whole genome sequencing resource identifies 18 new candidate genes for autism spectrum disorder". Nature Neuroscience. 20 (4): 602–611. doi:10.1038/nn.4524. PMC 5501701. PMID 28263302.

- ^ Krumm N, Turner TN, Baker C, Vives L, Mohajeri K, Witherspoon K, et al. (June 2015). "Excess of rare, inherited truncating mutations in autism". Nature Genetics. 47 (6): 582–588. doi:10.1038/ng.3303. PMC 4449286. PMID 25961944.

- ^ Mitani T, Isikay S, Gezdirici A, Gulec EY, Punetha J, Fatih JM, et al. (October 2021). "High prevalence of multilocus pathogenic variation in neurodevelopmental disorders in the Turkish population". American Journal of Human Genetics. 108 (10): 1981–2005. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.009. PMC 8546040. PMID 34582790.

- ^ Dhaliwal J, Qiao Y, Calli K, Martell S, Race S, Chijiwa C, et al. (July 2021). "Contribution of Multiple Inherited Variants to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in a Family with 3 Affected Siblings". Genes. 12 (7): 1053. doi:10.3390/genes12071053. PMC 8303619. PMID 34356069.

- ^ Aspromonte MC, Bellini M, Gasparini A, Carraro M, Bettella E, Polli R, et al. (September 2019). "Characterization of intellectual disability and autism comorbidity through gene panel sequencing". Human Mutation. 40 (9): 1346–1363. doi:10.1002/humu.23822. PMC 7428836. PMID 31209962.

- ^ "ASH1L curation results". search.clinicalgenome.org. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

Further reading

[edit]- Nagase T, Kikuno R, Ishikawa KI, Hirosawa M, Ohara O (February 2000). "Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XVI. The complete sequences of 150 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro". DNA Research. 7 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1093/dnares/7.1.65. PMID 10718198.

- Brandenberger R, Wei H, Zhang S, Lei S, Murage J, Fisk GJ, et al. (June 2004). "Transcriptome characterization elucidates signaling networks that control human ES cell growth and differentiation". Nature Biotechnology. 22 (6): 707–716. doi:10.1038/nbt971. PMID 15146197. S2CID 27764390.

- Colland F, Jacq X, Trouplin V, Mougin C, Groizeleau C, Hamburger A, et al. (July 2004). "Functional proteomics mapping of a human signaling pathway". Genome Research. 14 (7): 1324–1332. doi:10.1101/gr.2334104. PMC 442148. PMID 15231748.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Yamashita R, et al. (January 2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Research. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Vasilescu J, Zweitzig DR, Denis NJ, Smith JC, Ethier M, Haines DS, Figeys D (January 2007). "The proteomic reactor facilitates the analysis of affinity-purified proteins by mass spectrometry: application for identifying ubiquitinated proteins in human cells". Journal of Proteome Research. 6 (1): 298–305. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.401.4220. doi:10.1021/pr060438j. PMID 17203973.

External links

[edit]- Human ASH1L genome location and ASH1L gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative gene page on ASH1L

- Clinical Genome Resource information on ASH1L

- CARE4ASH1L family foundation for families affected by mutations in ASH1L