A Pale View of Hills

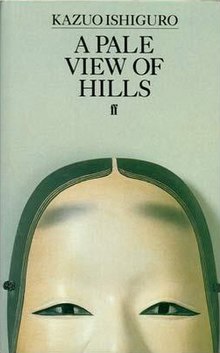

First edition cover | |

| Author | Kazuo Ishiguro |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Faber and Faber |

Publication date | February 1982 |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 192 pp (hardback first edition) |

| ISBN | 0-571-11866-6 (hardback first edition) |

| OCLC | 8303689 |

| Followed by | An Artist of the Floating World |

A Pale View of Hills (1982) is the first novel by Nobel Prize–winning author Kazuo Ishiguro. It won the 1982 Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize. He received a £1000 advance from publishers Faber and Faber for the novel after a meeting with Robert McCrum, the fiction editor.[1]

A Pale View of Hills is the story of Etsuko, a middle-aged Japanese woman living alone in England, and opens with discussion between Etsuko and her younger daughter, Niki, about the recent suicide of Etsuko's older daughter, Keiko.

Plot summary

[edit]During a visit from her daughter, Niki, Etsuko reflects on her own life as a young woman in Japan, and how she left that country to live in England. As she describes it, she and her Japanese husband, Jiro, had a daughter together, and a few years later Etsuko met a British man and moved with him to England. She took her elder daughter, Keiko, to England to live with her and the new husband. When Etsuko and her new husband have a daughter, Etsuko wants to call her something "modern" and her husband wants an Eastern-sounding name, so they compromise with the name "Niki", which seems to Etsuko to be perfectly British, but sounds to her husband at least slightly Japanese.

In England, Keiko becomes increasingly solitary and antisocial. Etsuko recalls how, as Keiko grew older, she would lock herself in her room and emerge only to pick up the dinner-plate that her mother would leave for her in the kitchen. This disturbing behavior ends, as the reader already has learned, in Keiko's suicide. "Your father," Etsuko tells Niki, "was rather idealistic at times...[H]e really believed we could give her a happy life over here... But you see, Niki, I knew all along. I knew all along she wouldn't be happy over here."[2]

Etsuko tells her daughter, Niki, that she had a friend in Japan named Sachiko. Sachiko had a daughter named Mariko, a girl whom Etsuko's memory paints as exceptionally solitary and antisocial. Sachiko, Etsuko recalls, had planned to take Mariko to America with an American soldier identified only as "Frank". Clearly, Sachiko's story bears striking similarities to Etsuko's.

Characters

[edit]- Etsuko – main protagonist; middle-aged Japanese woman

- Keiko – Etsuko's elder daughter who commits suicide

- Niki – Etsuko's second daughter, by her English husband

- Sachiko – woman known to Etsuko, and, possibly, a third person on whom Etsuko projects bad memories, thoughts, and events

- Mariko – Sachiko's daughter, and, possibly, a representation of Etsuko's daughter, Keiko

- Jiro – Etsuko's first husband

- Ogata-san – Jiro's father

- Frank – man that Sachiko was going to America with

- Mrs. Fujiwara – the owner of noodle shop who gave Sachiko a job

- Hanada – Jiro's friend who threatened his wife with a golf club

- Shigeo Matsuda – a student in Ogata-san's class

Reception

[edit]The novel was generally well received by critics, many praising the novel's mysterious tone. The New York Review of Books called it "eery and tenebrous. It is a ghost story but the narrator does not realise that."[3] The New York Times said the novel was "infinitely ... mysterious", and the inconsistent tone of the narrator, with the graphic imagery in the book combined to create "the absolute emblem of our genius of destruction".[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Nicholas Wroe (19 February 2005). "Living memories". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ Kazuo Ishiguro, A Pale View of Hills, pp.176

- ^ Annan, Gabriele. "On the High Wire". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "IN A JAPAN LIKE LIMBO". The New York Times. 9 May 1982. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Faber and Faber, Faber Book Club: A Pale View of Hills by Kazuo Ishiguro. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Kazuo Ishiguro discusses A Pale View of Hills with Malcolm Bradbury - a British Library sound recording