Act Without Words II

Act Without Words II is a short mime play by Samuel Beckett, his second (after Act Without Words I). Like many of Beckett's works, the piece was originally composed in French (Acte sans paroles II), then translated into English by Beckett himself. Written in the late 1950s[1] it opened at the Clarendon Press Institute in Oxford and was directed by John McGrath.[2] London premiere was directed by Michael Horovitz and performed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, on 25 January 1960.[2] The first printing was in New Departures 1, Summer 1959.

Synopsis

[edit]

Two sacks and a neat pile of clothes sit on a low, "violently lit"[4] platform at the back of a stage. Both sacks contain a man; B is on the left, A on the right.

A long pole (described in the text as a "goad") enters from the right, prods the sack containing A to awaken him to his daily routine, and then exits. After needing a second prod A finally emerges. He is unkempt and disorganised. He gobbles pills, prays, dresses randomly, nibbles a carrot, and promptly "spits it out with disgust".[4] "He is a moper, a hypochondriacal dreamer, perhaps a poet."[5] His principal activity, without apparent purpose, is to carry the filled sack stage left and crawl back into his own which he does leaving the sack containing B now vulnerable to the goad.

The goad reappears, this time with a wheel attachment, and prods the other sack, exiting as before. B is precise, efficient and eager; he only requires a single prod to rouse him. The clothes he – presumably – folded neatly before are now scattered about (clear evidence of the existence of a third party) but he never reacts to this and simply goes about his business. He knows how to dress and take care of his clothes. He takes greater care of himself (brushing his teeth and exercising), is better organised (he checks his watch – eleven times in total – and consults a map and compass before setting off to move the sacks), but still his shift is no more meaningful. Even though he has more to do than A, Beckett instructs that B performs his chores briskly so that they should take approximately the same time as A's. After moving the sacks he undresses and, rather than dumping his clothes in a pile, B folds them neatly before crawling into his own sack.

The goad appears for a third time (now requiring the support of two wheels) and attempts to wake A. Once again he needs two prods. He begins to replay his previous pantomime, but this time is cut off by a blackout, at which point the play ends.

Reception

[edit]The initial reviews ranged "from puzzled to disapproving"[6] and the play fared little better in America but for all that Beckett wrote to Thomas MacGreevy:[7] "I have never had such good notices." Alan Schneider believed the problem was that "[c]ritics can't seem to comment on what's before them without dragging in the older [plays] and rationalising their previous reactions."[8]

In 2000, Patrice Parks wrote in Monterey County Weekly that Act Without Words II “has lost not an iota of relevance to today''s mind-numbing workaday grind. If anything, Beckett''s work has been vindicated with the passage of time.”[9]

Interpretation

[edit]

"The play is compelling only if the mechanical figures are somehow humanised. If comfort exists it is because the plight of humanity if futile or repetitive is at least shared, even if no intercourse exists."[10] The two men work together to remove themselves from whatever external or elemental (see "Mana"[11]) force may be behind the goad; it counters by adding wheels. In time logic dictates they will reach a safe distance where they are beyond its reach but what then? Without it to motivate them, will they remain huddled in their sacks? Is that death?

Eugene Webb takes a different stance. He thinks that "the goad, represent[s] man's inner compulsion to activity. If man cannot rely on anything outside himself, is there anything inside him, which might prove worthy of his hope and trust? What Act Without Words II has to say about this is that man is driven by a compulsive force that will never let him withdraw for long into inaction."[12]

The Unnamable famously ends with, "I can't go on, I'll go on."[13] The goad represents what happens in between these two phrases. There is some similarity between the characters A and B and the protagonists of Beckett's Waiting for Godot, Vladimir and Estragon who spend their time in much the same way, engaged in pointless tasks to amuse themselves and while away the time, though ultimately never leading to anything of significance. That said, B is more businessman-like, "a kind of Pozzo ... grotesquely efficient, a workaholic, a health nut."[5] Between them they present "a composite picture of man":[12] B is self-reliant and proactive, A prefers to trust in an external god.

"Act Without Words II shows that life must be endured, if not understood. There are no triumphs, no resolution ... There is no control over the process, no"[11] seeing ‘the bigger picture’. "[N]either A or B appears to realise that each one of them carries the other on his back [or that there even is an other] ... they take their burden for granted"[5] as does Molloy, to cite a single example, who never questions how he has wound up in his mother's room being paid for writing stuff that only gets returned the next week covered in proofreading markings. Indeed, A evokes the vagrant Molloy in the same way as B recalls the detective Moran.

The action could take place in a day or two or perhaps over the course of their whole lives. The movement to the left is suggestive however of "the walk of Dante and Virgil in the Inferno."[14]

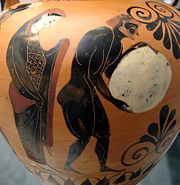

"In his reading of Le mythe de Sisyphe (The Myth of Sisyphus[15]) by Albert Camus, Beckett discovered a symbol for the futility, frustration and absurdity of all man's labours. Sisyphus – one of classical mythology's great sinners – suffered eternal punishment, having to perpetually roll a great stone to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back down again. Being born to enact and endure [an] eternal cycle of arousal-activity-rest, without any meaningful progress being achieved, is the sin that afflicts A-B."[16]

Film versions

[edit]The Goad

[edit]In 1965 Paul Joyce made a poignant film of the play titled The Goad featuring Freddie Jones and Geoffrey Hinsliff. It was published in a limited edition (500 copies) of Nothing Doing in London [No. 1] (London: Anthony Barnett, 1966).

NBC Production

[edit]NBC in America broadcast a version of Act without Words II in 1966, directed by Alan Schneider.

Beckett on Film

[edit]In the Beckett on Film project, the play was filmed as if it were a 1920s era black and white silent film.

Since Beckett had instructed that "the mime should be played on a low narrow platform at the back of [the] stage, violently lit in its entire length"[4] the director, Enda Hughes, chose, instead of a stage, to set the play "on" a strip of film being run through a movie projector. In place of a cut off by blackout, A's action is cut short by the projector being switched off. The action takes place across three frames thus complying with the "[f]rieze effect"[4] Beckett sought.

References

[edit]- ^ The Faber Companion to Samuel Beckett states that the work was written in 1958 (p 4), Eugene Webb in The Plays of Samuel Beckett says it was 1959 (pp 86-90), however Deirdre Bair, in Samuel Beckett: A Biography (p 500) indicates that he was working on this as far back as 1956

- ^ a b Schrank, Bernice; Demastes, William W. (1997). Irish playwrights, 1880-1995: a research and production sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 0-313-28805-4.

- ^ Redrawn according to the drawing on page 211 of The Complete Dramatic Works (Samuel Beckett, Faber & Faber, 2006).

- ^ a b c d Beckett, S., Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett (London: Faber and Faber, 1984), p 49

- ^ a b c Lamont, R. C., ‘To Speak the Words of "The Tribe": The Wordlessness of Samuel Beckett's Metaphysical Clowns’ in Burkman, K. H., (Ed.) Myth and Ritual in the Plays of Samuel Beckett (London and Toronto: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1987), p 63

- ^ Bair, D., Samuel Beckett: A Biography (London: Vintage, 1990), p 545

- ^ Samuel Beckett, letter to Thomas McGreevy, 9 February 1960

- ^ Bair, D., Samuel Beckett: A Biography (London: Vintage, 1990), p 546

- ^ Parks, Patrice. "Two plays by Samuel Beckett express the absurdity of life". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Ackerley, C. J. and Gontarski, S. E., (Eds.) The Faber Companion to Samuel Beckett, (London: Faber and Faber, 2006), p 4

- ^ a b Lamont, R. C., ‘To Speak the Words of "The Tribe": The Wordlessness of Samuel Beckett's Metaphysical Clowns’ in Burkman, K. H., (Ed.) Myth and Ritual in the Plays of Samuel Beckett (London and Toronto: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1987), p 57

- ^ a b Webb, E., Two Mimes: Act Without Words I and Act Without Words II Archived 7 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine in The Plays of Samuel Beckett (Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1974), pp 86-90

- ^ Beckett, S., Trilogy (London: Calder Publications, 1994), p 418

- ^ From a personal unpublished letter written by Samuel Beckett to the Polish critic and translator Antoni Libera. Referenced in Lamont, R. C., ‘To Speak the Words of "The Tribe": The Wordlessness of Samuel Beckett's Metaphysical Clowns’ in Burkman, K. H., (Ed.) Myth and Ritual in the Plays of Samuel Beckett (London and Toronto: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1987), p 70 n 28

- ^ According to The Faber Companion to Samuel Beckett (p 81), "SB considered L’Etranger (1942) important, but rejected the existentialism of Le mythe de Sisyphe." The mythological allusion remains intact however.

- ^ "Act Without Words 2 in Beckett on Film Project". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2007.