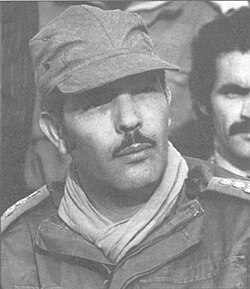

Ahmed Dlimi

Ahmed Dlimi أحمد دليمي | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 July 1931 Zaggota, Sidi Kacem Province, Morocco |

| Died | 25 January 1983 (aged 51) Marrakesh, Morocco |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1956–1983 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Western Sahara War Shaba I |

Ahmed Dlimi (b. 16 July 1931 in Zaggota, Sidi Kacem Province – d. 25 January 1983, Marrakesh) was a Moroccan General under the rule of Hassan II. After General Mohamed Oufkir's 1972 assassination, he became Hassan II's right-hand man. He led the Western Sahara War and played a major role in Angolan Civil War. He was promoted to General during the Green March in 1975, and took charge of the Moroccan Armed Forces in the Southern Zone, where the military were fighting the Polisario Front.[1][2][3][4]

Early life

[edit]Dlimi comes from a family originally from Zaggota, a village in the Chrarda region that is administratively part of Sidi Kacem Province. His father, Lahcen Dlimi, was a rural aristocrat falling over the Middle Eastern umbrella term of Pasha for his land-owning nature during the Protectorate Era. It was reported that it was Lahcen Dlimi who co-opted Mohammed Oufkir for a job in the colonial administration in the late 1940s.[5]

After the independence of Morocco, he briefly married the daughter of a minister, Messaoud Chiguer.[6] Then married a daughter of another minister, Bousselham.[6] This event opened the doors of the highest power circles for Dlimi, who was then a simple young officer in the army.[7]

Through his father Ahmed Dlimi was also related to Oufkir. Fatima Chenna, the wife of Oufkir and daughter of colonel Chenna, was related to Lahcen Dlimi through her mother.[5]

Before the Green March

[edit]Ahmed Dlimi headed the Moroccan security services and played an important role as a military supporter of King Hassan II during the Years of lead. A collaborator of Interior Minister Mohamed Oufkir, he was accused of numerous human rights violations. He was reportedly connected to the "disappearance" of the exiled opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka, leader of the left-wing National Union of Popular Forces (UNPF) and of the non-aligned Tricontinental Conference, in 1965, in Paris, France[8][9][10] According to the first judicial investigation, Ahmed Dlimi was in Paris, along with General Oufkir, at the time of Ben Barka's kidnapping.[11]

Former dissident and prisoner Ali Bourequat has also directly accused Dlimi of taking part in Ben Barka's assassination.[12]

After two failed coup attempts in 1971 and 1972 (the latter of which involved the assistance of General Oufkir), Dlimi was entrusted with increasingly important tasks and promoted to the rank of General. He eventually replaced Oufkir as right-hand man to Hassan II.[5]

After 1975

[edit]After the Green March in 1975, during which Morocco annexed Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony, General Dlimi became head of staff of the Moroccan Armed Forces in this territory. Western Sahara was then claimed both by Morocco and by the Polisario Front, which initiated a guerrilla against Rabat. In 1980, Dlimi initiated the construction of a wall, stating it was to protect the annexed Western Sahara from the Polisario's attacks. The latter became increasingly restricted to its base, Tindouf, in Algeria.[citation needed]

Ahmed Dlimi was increasingly viewed as the main military strongman of Morocco. However, in January 1983, he was killed in a car accident just after meeting the King in his palace at Marrakech. However, there are allegations that he was assassinated after attempting to organize a coup against King Hassan II,[13][14] or that he was killed for having become too powerful, and a threat to the monarchy.[15] The assassination theory has been supported by dissident Ahmed Rami in March 1983, who exiled himself to Sweden after the failed coup of 1972 in which he had taken part. Rami alleged that he had clandestinely met with Dlimi in Stockholm in December 1982, and that they were preparing a coup against Hassan II, due for July 1983.[16] Dlimi was allegedly part of the "Independent Officers" who intended to overthrow the monarchy, in order to put an end to the regime's corruption and human rights violations. They aimed to establish a "Democratic Arab Islamic Republic of Morocco" and to negotiate with the Polisario Front.[citation needed]

According to Ahmed Rami, several young military officers were arrested mid-January 1983. Dlimi himself was also arrested, interrogated and tortured in the royal palace, before his death being set up as a car-crash. Dlimi is said to have advocated a closer relationship to France in order to counter US influence.[17] Rami wrote that: "Hassan's closest circle, which also counts foreign secret agents, very well knows the circumstances of Dlimi's death."[16] This veiled allusion to the CIA was elaborated upon by Rami, who claimed that the CIA was investigating Dlimi as a secret member of the "Independent Officers"; that they had filmed the Stockholm meeting between them, and had ultimately delivered this video to Hassan II.[17] Morocco was at the time a very close ally of the United States. Hassan II had sent troops to Zaire in 1977 and 1978 to support US intervention, and also assisted UNITA in Angola since the mid-1970s. He had agreed to the setting up of a CIA station in Morocco, which became one of its key installations in Africa.[17] Hassan II had visited US Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and the State Secretary Al Haig in 1981, as well as the president of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the Deputy Director of the CIA.[17]

Death

[edit]He died in January 1983, officially in a car crash, although allegations have been made that he was assassinated. He was accused of being responsible for the death of Mehdi Ben Barka in November 1965. After Dlimi's death, fifteen other officers were arrested and three of them executed. No one was allowed to see Ahmed Dlimi's corpse.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "أحمد الدليمي". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- ^ "Pouvoir, luxure et trahison : l'histoire méconnue d'Ahmed Dlimi, l'homme qui a défié Hassan II". Telquel.ma (in French). Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- ^ "Qui a tué le général Ahmed Dlimi ?". Maghress. Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- ^ "الجنرال الدليمي شبح يخيف البوليساريو في حروب الصحراء..هل عاد الملك غير المتوج!؟ | وكالة ستيب الإخبارية" (in Arabic). Retrieved 2021-10-17.

- ^ a b c Ahmed Boukhari (2005). Raisons d'états: Tout sur l'affaire Ben Barka et d'autres crimes politiques au Maroc.

- ^ a b Abdellatif Mansour (4 March 2005). "Qui a tué le général Ahmed Dlimi ?". Maroc Hebdo. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ Mahjoub Tobji (2006). Les Officiers de Sa Majesté.

- ^ English account of revelations made in 2000 in Le Monde concerning the Ben Barka Affair (in English)

- ^ Interview with Bachir Ben Barka Archived 2005-12-20 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Morocco: Officer reveals CIA's role in Murder Archived 2011-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, The Irish Times, August 8, 2001 (in English)

- ^ Mehdi Ben Barka, quarante ans après, RFI, 29 October 2005 (in French)

- ^ Ali Bourequat, In the Moroccan King's Secret Garden, Maurice Publishers, 1998

- ^ Exit Hasan of Morocco: west mourns the death of another loyal servant Archived 2006-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Morocco: Breaking the Wall of Silence Archived 2006-05-01 at the Wayback Machine 1993 report from Amnesty International (AI Index: MDE 29/01/93)

- ^ The Morocco of Muhammad VI, The Estimate, July 30, 1999

- ^ a b Ahmed Rami, Le destin du général Dlimi (in French)

- ^ a b c d William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II, revised edition (Common Courage Press) ISBN 1-56751-252-6