Ahmed III Mosque

| Ahmed III Mosque | |

|---|---|

Ahmed III Mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| District | Corinthia |

| Province | Peloponnese |

| Status | Closed |

| Location | |

| Location | Acrocorinth, Greece |

| State | Greece |

| Geographic coordinates | 37°53′29″N 22°52′20″E / 37.89139°N 22.87222°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Founder | Ahmet III |

| Completed | 1715 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Minaret(s) | 1 (destroyed) |

| Materials | Stone, brick |

The Ahmed III Mosque (Greek: Τζαμί του Αχμέτ Γ΄), also known as the Acrocorinth Mosque (Greek: Τζαμί της Ακροκορίνθου) or the Ahmed Pasha Mosque (Turkish: Ahmet Paşa Camii),[1][a] is an Ottoman mosque located in the fortress of the Acrocorinth, in the Peloponnese, Greece. Built on the site of an earlier 16th-century mosque , the monument was commissioned by Sultan Ahmed III after the Ottoman reconquest of 1715. It now lies in a mostly ruinous state, abandoned and neglected, however it did undergo some restoration work in 2000.

History

[edit]It is one of the four in total mosques to have been built in the Acrocorinth.[5]

After the conquest of Corinth by the Ottoman troops of Sultan Mehmed II in 1458,[6][7] the citadel of the Acrocorinth was equipped with several mosques. The Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the region in 1668, mentioned four buildings punctuating the Islamic religious life of the fortress.[b][9] Probably dating from the 16th century, a first mosque in the northern part can be identified as the mosque of Ahmed Pasha or of Bayezid mentioned by Evliya Çelebi.[4][10] Two oak elements, recovered from wall masonry and in the minaret by archaeologists Richard Rothaus and Timothy E. Gregory, are dated 1489 and 1508.[11][12]

The mosque vaguely mentioned in 1668[13] was transformed into a powder magazine during the second period of Venetian occupation between 1687 and 1715.[4][7][14] At the very end of the 17th century, a plan of the Acrocorinth by the engineer Pierre de la Salle, in the Gennadius Library, indicates that the place also served as a storage for biscuits intended for the garrison, also called bread of ammunition.[15] Shortly after the recapture of the fortress by the Ottomans in 1715, a new mosque was erected by Sultan Ahmed III on the ruins of previous constructions.[16]

The mosque was studied by archaeologists Antoine Bon and Rhys Carpenter in 1936.[12] During the 2000s, the building underwent consolidation work, directed mainly towards the structural reinforcement of the windows and the minaret.[17]

Architecture

[edit]The Ahmed III Mosque, which measures 8.50 × 9.50 meters,[18] has the characteristics and the simple plan of the first Ottoman mosques in the Balkans.[4][19][20] Traces of the earlier mosque are still identifiable today, particularly in the pointed style of the openings, typical of the early Ottoman period.

The general masonry is particularly heterogeneous, consisting mainly of limestone and a few randomly arranged bricks.[4] The exterior walls of 0.70 meter[18] are more controlled in the corners and for the base of the minaret, where materials from older buildings have been integrated. On the main facade to the north are traces of the arrangements of the second Venetian period, in particular the use of voussoirs at the top of the door and the lion of Saint Mark, emblem of the Republic of Venice.[4][18]

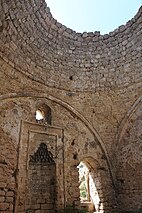

The base of the minaret, preserving within it the spiral staircase, is located at the northwest corner of the mosque, at the level of the porch of which only a few sections of exterior walls remain on the eastern side.[21] A large cupola on squinches,[18] partially destroyed since the end of the twentieth century due to lack of maintenance, surmounts the square prayer hall. In the center of the south wall, framed by two windows, the building has a mihrab in the Turkish Baroque style is still visible to this today. The muqarnas niche has an ornate double rectangular frame.[21]

Gallery

[edit]- The Mosque of Ahmed III

-

The mosque over the Corinthian Gulf.

-

Mosque, minaret and Frankish tower.

-

View of the mosque from the south.

-

Minaret at the northwest.

-

Interior of the mosque.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports identifies this monument dating from the first period of Ottoman rule as "Mosque I",[2] thus differentiating it from "Mosque II" located approximately 110 meters to the south.[3] However, the reference ministerial publication on Ottoman architecture in Greece more simply designates the building as the “Mosque of the Acrocorinth”.[4]

- ^ In this case three large mosques for Friday prayer (cami) and a small mosque for daily prayer (mesjid).[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Kiel 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Ministry of Culture and Sports. "Τέμενος Α΄" [Mosque I]. www.odysseus.culture.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ Ministry of Culture and Sports. "Τέμενος B΄" [Mosque II]. www.odysseus.culture.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Koumousi 2008, p. 136.

- ^ Konstantina Skarmoutsou. "Κάστρο Ακροκορίνθου" [Castle of the Acrocorinth]. odysseus.culture.gr (in Greek). Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Ameen 2017, p. 13.

- ^ a b Kiel, Machiel (1996). "Gördüş". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 14 (Geli̇bolu – Haddesenâ) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-975-389-441-8.

- ^ Kiel 2016, p. 58.

- ^ Ephorate of Antiquities of Corinthia. "Acrocorinth – Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth". www.corinth-museum.gr. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Demetropoulou, Magdalene (2018). Ενοποίηση αρχαιολογικών χώρων Αρχαίας Κορίνθου, Ακροκορίνθου και Λεχαίου και δημιουργία αρχαιολογικού - περιβαλλοντικού πάρκου [Consolidation of the Archaeological Sites of Ancient Corinth, the Acrocorinth and Lechaeum and creation of an archaeological-environmental park] (PDF) (in Greek). Patras: Open University of Greece. p. 84. ISBN 9780007094493.

- ^ Baram, Uzi; Carroll, Lynda (2006). A Historical Archaeology of the Ottoman Empire: Breaking New Ground. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-306-47182-7. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ a b Kuniholm, Peter Ian (1997). "Aegean Dendrochronology Project: 1995–1996 results" (PDF). Arkeometrı Sonuçlari Toplantisi. 12: 163–175. ISSN 1017-7671.

- ^ Ameen 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Kiel 2016, p. 59.

- ^ Éric Guillaume Luc Pinzelli (1997). The defense of the Isthmus of Corinth during the Venetian period (1687-1715). University of Provence Aix-Marseille I. pp. 9–10, 180 and 1998–199.

- ^ Kiel 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Athanasoulis, Demetrios (2009). Το κάστρο του Ακροκορίνθου και η ανάδειξή του (2006-2009) [The castle of the Acrocorinth and its Exposition (2006–2009)] (in Greek). 25th Ephorate of Byzantine antiquities. p. 109. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- ^ a b c d "Acrocorinth Mosque (Τζαμιού του Ακροκόρινθου)". www.madainproject.com (in Greek). Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Chrysáfi-Zográfou, Metaxoula. "Τουρκικά κτίσματα στην Κόρινθο. Κρήνες και θρησκευτικά" [Turkish buildings in Corinth. Fountains and Religious Buildings]. Restoration-Maintenance-Protection of Monuments and Ensembles. 1.1984. Athens: Ministry of Culture and Sports: 273–275.

- ^ MacKay, Pierre (1968). "Acrocorinth in 1668, a Turkish Account". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 37 (4): 386–397. doi:10.2307/147608. ISSN 0018-098X. JSTOR 147608.

- ^ a b Kiel 2016, p. 64.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ameen, Ahmed (2017). Islamic architecture in Greece: Mosques. Alexandria: Center for Islamic Civilization studies, Bibliotheca Alexandrina. ISBN 9774524349.

- Kiel, Machiel (2016). "Corinth in the Ottoman period (1458-1687 and 1715-1821) : the afterlife of a great ancient Greek and Roman metropolis" (PDF). Shedet. 3 (5): 45–71. doi:10.21608/shedet.003.05. ISSN 2356-8704.

- Koumousi, Anastasia (2008). "Mosque of Acrocorinth". In Ersi Brouskari (ed.). Ottoman architecture in Greece. Translated by Elizabeth Key Fowden. Athens: Ministry of Culture and Sports. p. 136. ISBN 978-960-214-792-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Ahmed III Mosque at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ahmed III Mosque at Wikimedia Commons