Apolipoprotein D

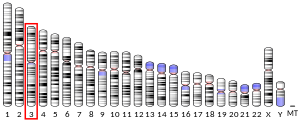

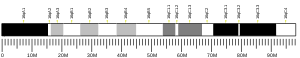

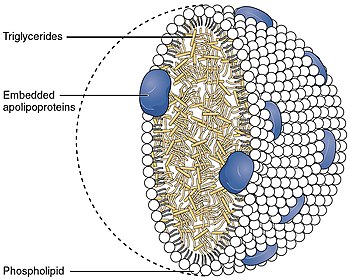

Apolipoprotein D (ApoD) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the APOD gene.[5][6][7] Unlike other lipoproteins, which are mainly produced in the liver, apolipoprotein D is mainly produced in the brain and testes.[8] It is a 29 kDa glycoprotein discovered in 1963 as a component of the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) fraction of human plasma.[9][10] It is the major component of human mammary cyst fluid. The human gene encoding it was cloned in 1986 and the deduced protein sequence revealed that ApoD is a member of the lipocalin family, small hydrophobic molecule transporters.[6] ApoD is 169 amino acids long, including a secretion peptide signal of 20 amino acids. It contains two glycosylation sites (aspargines 45 and 78) and the molecular weight of the mature protein varies from 20 to 32 kDa (see figure 1).

The resolved tertiary structure shows that ApoD is composed of 8 anti-parallel β-strands forming a hydrophobic cavity capable of receiving different ligands.[11][12] ApoD also contains 5 cysteine residues, 4 of which are involved in intra-molecular disulfide bonds.

Function

[edit]Apolipoprotein D (ApoD) is a component of HDL that has no marked similarity to other apolipoprotein sequences. It has a high degree of homology to plasma retinol-binding protein and other members of the alpha 2 microglobulin protein superfamily of carrier proteins, also known as lipocalins. It is a glycoprotein of estimated molecular weight 33 KDa. Apo-D is closely associated with the enzyme lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) - an enzyme involved in lipoprotein metabolism.[7] ApoD has also been shown to be an important link in the transient interaction between HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and between HDL particles and cells.[13]

Interactions and ligands

[edit]ApoD was shown to bind steroid hormones such as progesterone and pregnenolone with a relatively strong affinity, and to estrogens with a weaker affinity.[14][15] Molecular modeling studies identified bilirubin, a breakdown product of heme, as a potential ligand.[11] Arachidonic acid (AA) was identified as an ApoD ligand with a much better affinity than that of progesterone or pregnenolone.[16] AA is the precursor of prostaglandins and leukotrienes, molecules that are involved in inflammation, platelet aggregation and cellular regulation.[17] A very poor binding between ApoD and cholesterol has also been observed.[18] Other ApoD ligands include E-3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid, a scent molecule present in body odor secretions;[19] retinoic acid, which is involved in cellular differentiation; and sphingomyelin and sphingolipids, which are major components of HDL and cell membranes.[20] The fact that apoD may bind such a large variety of ligands strongly support the hypothesis that it could be a multi-ligand, multi-functional protein.

Clinical significance

[edit]APOD is a biomarker of androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). APOD is an androgen up-regulated gene in normal scrotal fibroblast cells in comparison to labia majora cells in females with complete AIS (CAIS).[21] APOD is associated with neurological disorders and nerve injury, especially related to myelin sheath. APOD was shown to be elevated in a rat model of stroke.[8] APOD is elevated in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and Alzheimer's disease.[8]

ApoD expression in cells and tissues

[edit]Analysis of the ApoD gene promoter region identified a large number of promoter regulatory elements, among which are response elements to steroids (such as estrogen and progesterone) and glucocorticoids. Response elements to fatty acids, acute phase proteins, serum, and to the immune factor NF-κB were also observed.[22][23][24] The presence of such a large number of regulatory sequences suggests that the regulation of its expression is very complex.

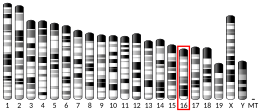

ApoD has been identified in 6 mammalian species as well as in chickens,[25][26] fruit flies,[27] plants[28] and bacteria.[29] In humans, monkeys, rabbits and guinea pigs, ApoD is highly expressed in the nervous system (brain, cerebellum, and peripheral nerves). Otherwise, expression levels of ApoD vary largely from organ to organ and species to species, with humans displaying the most diverse expression of ApoD, and mice and rats almost exclusively expressing ApoD in the nervous system (see Figure 2).

ApoD concentration in human plasma varies between 5 and 23 mg/100 ml.[30] In the nervous system, the ApoD mRNA is expressed by fibroblasts, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes[31][32][33] As a glycoprotein with a peptide signal, ApoD is secreted. Yet it can also be actively reinternalized. The transmembrane glycoprotein Basigin (BSG; CD147) was identified as an ApoD receptor.[34] BSG is a membrane glycoprotein receptor, a member of the immunoglobulin family, involved in several pathologies such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease.[35]

Modulation of ApoD expression

[edit]Studies on several cell types have shown that ApoD expression can be induced by several stressing situations such as growth arrest, senescence, oxidative and inflammatory stresses.[23][24] ApoD expression is also increased in several neuropathologies. ApoD expression is modulated in several pathologies such as HDL familial deficiency, Tangier disease,[36][37] LCAT familial deficit[38] and type 2 diabetes.[39] It is overexpressed in numerous cancers,[40] including breast,[41][42] ovary, prostate,[43] skin[44][45] and central nervous system (CNS) cancer. In many cases, its expression is correlated with highly differentiated, non-invasive and non-metastatic state.

A role in lipid metabolism has been identified for ApoD by a study on transgenic (Tg) mice overexpressing human ApoD in the CNS.[46] These mice slowly develop a hepatic and muscular steatosis accompanied with insulin resistance. However, none of the Tg mice develop obesity nor diabetes. ApoD induced lipid accumulation is not due to de novo lipogenesis but rather from increased lipid uptake in response to prostaglandin overproduction.[47]

Plasma ApoD levels decrease significantly during normal uncomplicated pregnancy. ApoD is further decreased in women with excessive gestational weight gain and their newborns. In these women, the ApoD concentration was tightly associated with the lipid parameters.[48] In morbidly obese women (BMI over 40) adipose tissues, ApoD protein expression is positively correlated with parameters of metabolic health. ApoD-null female mice (mice in which the ApoD gene was inactivated) present progressive (up to 50%) bone volume reduction with aging.[49]

ApoD and the nervous system

[edit]Both ApoD and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) protein levels increase drastically at the site of regeneration following a nerve crush injury in the rat.[50][51] Similar observations have been made in rabbits, marmoset monkeys and in mice.[52] Elevated levels of ApoD were observed in the cerebrospinal fluid, hippocampus and cortex of human patients with Alzheimer's disease, cerebrovascular disease, motoneuron disease, meningoencephalitis and stroke.[53] ApoD expression is altered in plasma and post-mortem brains of patients with schizophrenia.[54] In patients with Parkinson's disease or with multiple sclerosis, ApoD expression is strongly increased in glial cells of the substantia nigra.[55][56]

Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) is a genetic disorder affecting cholesterol transport that is accompanied by chronic progressive neurodegeneration. In animal models of NPC, ApoD expression is increased in the plasma and the brain.[57] In rats, ApoD expression increases in the hippocampus after enthorinal cortex lesioning. ApoD mRNA and protein increases in the ipsilateral region of hippocampus as early as 2 days post-lesion (DPL), remains high for 10 days and returns to normal after 14 DPL, a period considered necessary for a complete reinervation.[58] Similar results are obtained after injection of kainic acid, an analog of glutamic acid which causes a severe neurodegenerative injury in the hippocampus[59] or after experimentally-induced stoke.[60][61] ApoD expression is also increased in the aging brain.[53] Altogether, these data suggest that ApoD plays an important role in neural preservation and protection.

Tg mice are less sensitive to oxidative stress induced by paraquat, a free oxygen radical generator, and present reduced lipid peroxidation levels. In contrast, apoD-null mice show increased sensitivity to oxidative stress, increased brain lipid peroxidation and impaired locomotor and learning abilities. Similar results have been observed in a drosophila model.[62] Mice infected with the human coronavirus OC43 develop encephalitis and inflammatory demyelination of the CNS, a disease very similar to multiple sclerosis. Tg mice infected with OC43 display increased survivability compared to control animals.[63] Tg mice treated with kainic acid show a significant reduction of inflammatory responses and a much stronger protection against apoptosis in the hippocampus than control animals.[64] ApoD-null mice crossed with APP-PS1 mice, a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease, displayed a 2-fold increase of hippocampal amyloid plaque load. In contrast, the progeny of Tg mice crossed with APP-PS1 mice displayed reduced hippocampal plaque load by 35%, and a 35% to 65% reduction of amyloid peptide levels.[65]

Notes

[edit]

The 2020 version of this article was updated by an external expert under a dual publication model. The corresponding academic peer reviewed article was published in Gene and can be cited as: Eric Rassart, Frederik Desmarais, Ouafa Najyb, Karl-F Bergeron, Catherine Mounier (15 June 2020). "Apolipoprotein D". Gene. Gene Wiki Review Series: 144874. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2020.144874. ISSN 0378-1119. PMC 8011330. PMID 32554047. Wikidata Q96587699. |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000189058 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022548 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Drayna DT, McLean JW, Wion KL, Trent JM, Drabkin HA, Lawn RM (June 1987). "Human apolipoprotein D gene: gene sequence, chromosome localization, and homology to the alpha 2u-globulin superfamily". DNA. 6 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1089/dna.1987.6.199. PMID 2439269.

- ^ a b Drayna D, Fielding C, McLean J, Baer B, Castro G, Chen E, et al. (December 1986). "Cloning and expression of human apolipoprotein D cDNA". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 261 (35): 16535–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)66599-8. PMID 3453108.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: APOD apolipoprotein D".

- ^ a b c Muffat J, Walker DW (January 2010). "Apolipoprotein D: an overview of its role in aging and age-related diseases". Cell Cycle. 9 (2): 269–73. doi:10.4161/cc.9.2.10433. PMC 3691099. PMID 20023409.

- ^ Ayrault Jarrier M, Levy G, Polonovski J (August 1963). "[Study of Human Serum Alpha-Lipoproteins by Immunoelectrophoresis]". Bulletin de la Société de Chimie Biologique. 45: 703–13. PMID 14051455.

- ^ McConathy WJ, Alaupovic P (February 1976). "Studies on the isolation and partial characterization of apolipoprotein D and lipoprotein D of human plasma". Biochemistry. 15 (3): 515–20. doi:10.1021/bi00648a010. PMID 56198.

- ^ a b Peitsch MC, Boguski MS (February 1990). "Is apolipoprotein D a mammalian bilin-binding protein?". The New Biologist. 2 (2): 197–206. PMID 2083249.

- ^ Eichinger A, Nasreen A, Kim HJ, Skerra A (October 2007). "Structural insight into the dual ligand specificity and mode of high density lipoprotein association of apolipoprotein D". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (42): 31068–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M703552200. PMID 17699160. S2CID 9647650.

- ^ Braesch-Andersen S, Beckman L, Paulie S, Kumagai-Braesch M (December 2014). "ApoD mediates binding of HDL to LDL and to growing T24 carcinoma". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e115180. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5180B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115180. PMC 4267786. PMID 25513803.

- ^ Pearlman WH, Guériguian JL, Sawyer ME (August 1973). "A specific progesterone-binding component of human breast cyst fluid". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 248 (16): 5736–41. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)43566-7. PMID 4723913.

- ^ Lea OA (October 1988). "Binding properties of progesterone-binding Cyst protein, PBCP". Steroids. 52 (4): 337–8. doi:10.1016/0039-128x(88)90135-3. PMID 3250014. S2CID 26492300.

- ^ Morais Cabral JH, Atkins GL, Sánchez LM, López-Boado YS, López-Otin C, Sawyer L (June 1995). "Arachidonic acid binds to apolipoprotein D: implications for the protein's function". FEBS Letters. 366 (1): 53–6. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)00484-q. PMID 7789516. S2CID 9063157.

- ^ Kuehl FA J, Egan RW (28 November 1980). "Prostaglandins, arachidonic acid, and inflammation". Science. 210 (4473): 978–84. Bibcode:1980Sci...210..978K. doi:10.1126/science.6254151. PMID 6254151.

- ^ Patel RC, Lange D, McConathy WJ, Patel YC, Patel SC (June 1997). "Probing the structure of the ligand binding cavity of lipocalins by fluorescence spectroscopy". Protein Engineering. 10 (6): 621–5. doi:10.1093/protein/10.6.621. PMID 9278274.

- ^ Zeng C, Spielman AI, Vowels BR, Leyden JJ, Biemann K, Preti G (June 1996). "A human axillary odorant is carried by apolipoprotein D". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (13): 6626–30. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.6626Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6626. PMC 39076. PMID 8692868.

- ^ Breustedt DA, Schönfeld DL, Skerra A (February 2006). "Comparative ligand-binding analysis of ten human lipocalins". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1764 (2): 161–73. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.12.006. PMID 16461020.

- ^ Appari M, Werner R, Wünsch L, Cario G, Demeter J, Hiort O, et al. (June 2009). "Apolipoprotein D (APOD) is a putative biomarker of androgen receptor function in androgen insensitivity syndrome". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 87 (6): 623–32. doi:10.1007/s00109-009-0462-3. PMC 5518750. PMID 19330472.

- ^ Lambert J, Provost PR, Marcel YL, Rassart E (20 February 1993). "Structure of the human apolipoprotein D gene promoter region". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Structure and Expression. 1172 (1–2): 190–2. doi:10.1016/0167-4781(93)90292-l. PMID 7916629.

- ^ a b Do Carmo S, Séguin D, Milne R, Rassart E (15 February 2002). "Modulation of apolipoprotein D and apolipoprotein E mRNA expression by growth arrest and identification of key elements in the promoter". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (7): 5514–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105057200. PMID 11711530. S2CID 45692527.

- ^ a b Do Carmo S, Levros LC J, Rassart E (June 2007). "Modulation of apolipoprotein D expression and translocation under specific stress conditions". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1773 (6): 954–69. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.007. PMID 17477983.

- ^ Vieira AV, Lindstedt K, Schneider WJ, Vieira PM (December 1995). "Identification of a circulatory and oocytic avian apolipoprotein D". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 42 (4): 443–6. doi:10.1002/mrd.1080420411. PMID 8607974. S2CID 34209685.

- ^ Ganfornina MD, Sánchez D, Pagano A, Tonachini L, Descalzi-Cancedda F, Martínez S (January 2005). "Molecular characterization and developmental expression pattern of the chicken apolipoprotein D gene: implications for the evolution of vertebrate lipocalins". Developmental Dynamics. 232 (1): 191–9. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20193. PMID 15580625. S2CID 14396229.

- ^ Sánchez D, Ganfornina MD, Torres-Schumann S, Speese SD, Lora JM, Bastiani MJ (June 2000). "Characterization of two novel lipocalins expressed in the Drosophila embryonic nervous system". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 44 (4): 349–59. PMID 10949044.

- ^ Frenette Charron JB, Breton G, Badawi M, Sarhan F (24 April 2002). "Molecular and structural analyses of a novel temperature stress-induced lipocalin from wheat and Arabidopsis". FEBS Letters. 517 (1–3): 129–32. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02606-6. PMID 12062422. S2CID 34705682.

- ^ Bishop RE, Penfold SS, Frost LS, Höltje JV, Weiner JH (29 September 1995). "Stationary phase expression of a novel Escherichia coli outer membrane lipoprotein and its relationship with mammalian apolipoprotein D. Implications for the origin of lipocalins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (39): 23097–103. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.39.23097. PMID 7559452. S2CID 2904679.

- ^ Camato R, Marcel YL, Milne RW, Lussier-Cacan S, Weech PK (June 1989). "Protein polymorphism of a human plasma apolipoprotein D antigenic epitope". Journal of Lipid Research. 30 (6): 865–75. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)38304-8. PMID 2477480.

- ^ Smith KM, Lawn RM, Wilcox JN (June 1990). "Cellular localization of apolipoprotein D and lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase mRNA in rhesus monkey tissues by in situ hybridization". Journal of Lipid Research. 31 (6): 995–1004. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)42739-7. PMID 2373967.

- ^ Provost PR, Marcel YL, Milne RW, Weech PK, Rassart E (23 September 1991). "Apolipoprotein D transcription occurs specifically in nonproliferating quiescent and senescent fibroblast cultures". FEBS Letters. 290 (1–2): 139–41. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)81244-3. PMID 1915865. S2CID 20185401.

- ^ Provost PR, Villeneuve L, Weech PK, Milne RW, Marcel YL, Rassart E (December 1991). "Localization of the major sites of rabbit apolipoprotein D gene transcription by in situ hybridization". Journal of Lipid Research. 32 (12): 1959–70. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)41899-1. PMID 1816324.

- ^ Najyb O, Brissette L, Rassart E (26 June 2015). "Apolipoprotein D Internalization Is a Basigin-dependent Mechanism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (26): 16077–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.644302. PMC 4481210. PMID 25918162.

- ^ Iacono KT, Brown AL, Greene MI, Saouaf SJ (December 2007). "CD147 immunoglobulin superfamily receptor function and role in pathology". Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 83 (3): 283–95. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.08.014. PMC 2211739. PMID 17945211.

- ^ Bodzioch M, Orsó E, Klucken J, Langmann T, Böttcher A, Diederich W, et al. (August 1999). "The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease". Nature Genetics. 22 (4): 347–51. doi:10.1038/11914. PMID 10431237. S2CID 26890624.

- ^ Alaupovic P, Schaefer EJ, McConathy WJ, Fesmire JD, Brewer HB J (August 1981). "Plasma apolipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein A-I and A-II deficiency (Tangier disease)". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 30 (8): 805–9. doi:10.1016/0026-0495(81)90027-5. PMID 6790903.

- ^ Albers JJ, Adolphson J, Chen CH, Murayama N, Honma S, Akanuma Y (9 July 1985). "Defective enzyme causes lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency in a Japanese kindred". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 835 (2): 253–7. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(85)90280-2. PMID 4005283.

- ^ Baker WA, Hitman GA, Hawrami K, McCarthy MI, Riikonen A, Tuomilehto-Wolf E, et al. (December 1994). "Apolipoprotein D gene polymorphism: a new genetic marker for type 2 diabetic subjects in Nauru and south India". Diabetic Medicine. 11 (10): 947–52. doi:10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00252.x. PMID 7895459. S2CID 24833816.

- ^ Ryu B, Jones J, Hollingsworth MA, Hruban RH, Kern SE (1 March 2001). "Invasion-specific genes in malignancy: serial analysis of gene expression comparisons of primary and passaged cancers". Cancer Research. 61 (5): 1833–8. PMID 11280733.

- ^ Díez-Itza I, Vizoso F, Merino AM, Sánchez LM, Tolivia J, Fernández J, et al. (February 1994). "Expression and prognostic significance of apolipoprotein D in breast cancer". The American Journal of Pathology. 144 (2): 310–20. PMC 1887137. PMID 8311115.

- ^ Søiland H, Skaland I, Varhaug JE, Kørner H, Janssen EA, Gudlaugsson E, et al. (2009). "Co-expression of estrogen receptor alpha and Apolipoprotein D in node positive operable breast cancer--possible relevance for survival and effects of adjuvant tamoxifen in postmenopausal patients". Acta Oncologica. 48 (4): 514–21. doi:10.1080/02841860802620613. PMID 19107621. S2CID 22404040.

- ^ Aspinall JO, Bentel JM, Horsfall DJ, Haagensen DE, Marshall VR, Tilley WD (August 1995). "Differential expression of apolipoprotein-D and prostate specific antigen in benign and malignant prostate tissues". The Journal of Urology. 154 (2 Pt 1): 622–8. doi:10.1097/00005392-199508000-00082. PMID 7541868.

- ^ Miranda E, Vizoso F, Martín A, Quintela I, Corte MD, Seguí ME, et al. (June 2003). "Apolipoprotein D expression in cutaneous malignant melanoma". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 83 (2): 99–105. doi:10.1002/jso.10245. PMID 12772203. S2CID 25700567.

- ^ West RB, Harvell J, Linn SC, Liu CL, Prapong W, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. (August 2004). "Apo D in soft tissue tumors: a novel marker for dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 28 (8): 1063–9. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000126857.86186.4c. PMID 15252314. S2CID 5773777.

- ^ Do Carmo S, Fournier D, Mounier C, Rassart E (April 2009). "Human apolipoprotein D overexpression in transgenic mice induces insulin resistance and alters lipid metabolism". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 296 (4): E802-11. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.90725.2008. PMID 19176353.

- ^ Desmarais F, Bergeron KF, Rassart E, Mounier C (April 2019). "Apolipoprotein D overexpression alters hepatic prostaglandin and omega fatty acid metabolism during the development of a non-inflammatory hepatic steatosis" (PDF). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1864 (4): 522–531. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.01.001. PMID 30630053. S2CID 58594626.

- ^ Do Carmo S, Forest JC, Giguère Y, Masse A, Lafond J, Rassart E (2 September 2009). "Modulation of Apolipoprotein D levels in human pregnancy and association with gestational weight gain". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 7: 92. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-7-92. PMC 3224896. PMID 19723339.

- ^ Martineau C, Najyb O, Signor C, Rassart É, Moreau R (September 2016). "Apolipoprotein D deficiency is associated to high bone turnover, low bone mass and impaired osteoblastic function in aged female mice". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 65 (9): 1247–58. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2016.05.007. PMC 7094319. PMID 27506732.

- ^ Boyles JK, Notterpek LM, Anderson LJ (15 October 1990). "Accumulation of apolipoproteins in the regenerating and remyelinating mammalian peripheral nerve. Identification of apolipoprotein D, apolipoprotein A-IV, apolipoprotein E, and apolipoprotein A-I". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (29): 17805–15. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)38235-8. PMID 2120218.

- ^ Boyles JK, Notterpek LM, Wardell MR, Rall SC J (December 1990). "Identification, characterization, and tissue distribution of apolipoprotein D in the rat". Journal of Lipid Research. 31 (12): 2243–56. doi:10.1016/S0022-2275(20)42112-1. PMID 2090718.

- ^ Ganfornina MD, Do Carmo S, Martínez E, Tolivia J, Navarro A, Rassart E, et al. (15 August 2010). "ApoD, a glia-derived apolipoprotein, is required for peripheral nerve functional integrity and a timely response to injury". Glia. 58 (11): 1320–34. doi:10.1002/glia.21010. PMC 7165554. PMID 20607718.

- ^ a b Terrisse L, Poirier J, Bertrand P, Merched A, Visvikis S, Siest G, et al. (October 1998). "Increased levels of apolipoprotein D in cerebrospinal fluid and hippocampus of Alzheimer's patients". Journal of Neurochemistry. 71 (4): 1643–50. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041643.x. PMID 9751198. S2CID 24675226.

- ^ Thomas EA, Dean B, Pavey G, Sutcliffe JG (27 March 2001). "Increased CNS levels of apolipoprotein D in schizophrenic and bipolar subjects: implications for the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (7): 4066–71. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.4066T. doi:10.1073/pnas.071056198. PMC 31180. PMID 11274430.

- ^ Reindl M, Knipping G, Wicher I, Dilitz E, Egg R, Deisenhammer F, et al. (1 October 2001). "Increased intrathecal production of apolipoprotein D in multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 119 (2): 327–32. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00378-2. PMID 11585636. S2CID 24583456.

- ^ Ordoñez C, Navarro A, Perez C, Astudillo A, Martínez E, Tolivia J (April 2006). "Apolipoprotein D expression in substantia nigra of Parkinson disease". Histology and Histopathology. 21 (4): 361–6. doi:10.14670/HH-21.361. PMID 16437381.

- ^ Yoshida K, Cleaveland ES, Nagle JW, French S, Yaswen L, Ohshima T, et al. (October 1996). "Molecular cloning of the mouse apolipoprotein D gene and its upregulated expression in Niemann-Pick disease type C mouse model". DNA and Cell Biology. 15 (10): 873–82. doi:10.1089/dna.1996.15.873. PMID 8892759.

- ^ Terrisse L, Séguin D, Bertrand P, Poirier J, Milne R, Rassart E (18 June 1999). "Modulation of apolipoprotein D and apolipoprotein E expression in rat hippocampus after entorhinal cortex lesion". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 70 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00123-0. PMID 10381540.

- ^ Ong WY, He Y, Suresh S, Patel SC (July 1997). "Differential expression of apolipoprotein D and apolipoprotein E in the kainic acid-lesioned rat hippocampus". Neuroscience. 79 (2): 359–67. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00608-2. PMID 9200721. S2CID 11857861.

- ^ Rickhag M, Wieloch T, Gidö G, Elmér E, Krogh M, Murray J, et al. (January 2006). "Comprehensive regional and temporal gene expression profiling of the rat brain during the first 24 h after experimental stroke identifies dynamic ischemia-induced gene expression patterns, and reveals a biphasic activation of genes in surviving tissue". Journal of Neurochemistry. 96 (1): 14–29. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03508.x. PMID 16300643. S2CID 23231070.

- ^ Rickhag M, Deierborg T, Patel S, Ruscher K, Wieloch T (March 2008). "Apolipoprotein D is elevated in oligodendrocytes in the peri-infarct region after experimental stroke: influence of enriched environment". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 28 (3): 551–62. doi:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600552. PMID 17851453. S2CID 25611779.

- ^ Ganfornina MD, Do Carmo S, Lora JM, Torres-Schumann S, Vogel M, Allhorn M, et al. (August 2008). "Apolipoprotein D is involved in the mechanisms regulating protection from oxidative stress". Aging Cell. 7 (4): 506–15. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00395.x. PMC 2574913. PMID 18419796.

- ^ Do Carmo S, Jacomy H, Talbot PJ, Rassart E (8 October 2008). "Neuroprotective effect of apolipoprotein D against human coronavirus OC43-induced encephalitis in mice". The Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (41): 10330–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2644-08.2008. PMC 6671015. PMID 18842892.

- ^ Najyb O, Do Carmo S, Alikashani A, Rassart E (August 2017). "Apolipoprotein D Overexpression Protects Against Kainate-Induced Neurotoxicity in Mice". Molecular Neurobiology. 54 (6): 3948–3963. doi:10.1007/s12035-016-9920-4. PMC 7091089. PMID 27271124.

- ^ Li H, Ruberu K, Muñoz SS, Jenner AM, Spiro A, Zhao H, et al. (May 2015). "Apolipoprotein D modulates amyloid pathology in APP/PS1 Alzheimer's disease mice". Neurobiology of Aging. 36 (5): 1820–33. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.02.010. PMID 25784209. S2CID 15335129.

Further reading

[edit]- Rassart E, Bedirian A, Do Carmo S, Guinard O, Sirois J, Terrisse L, et al. (October 2000). "Apolipoprotein D". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1482 (1–2): 185–98. doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00162-X. PMID 11058760. S2CID 8189847.

- Peitsch MC, Boguski MS (February 1990). "Is apolipoprotein D a mammalian bilin-binding protein?". The New Biologist. 2 (2): 197–206. PMID 2083249.

- Balbín M, Freije JM, Fueyo A, Sánchez LM, López-Otín C (November 1990). "Apolipoprotein D is the major protein component in cyst fluid from women with human breast gross cystic disease". The Biochemical Journal. 271 (3): 803–7. doi:10.1042/bj2710803. PMC 1149635. PMID 2244881.

- Drayna D, Scott JD, Lawn R (November 1987). "Multiple RFLPs at the human apolipoprotein D (APOD) locus". Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (22): 9617. doi:10.1093/nar/15.22.9617. PMC 306509. PMID 2891117.

- Fielding PE, Fielding CJ (June 1980). "A cholesteryl ester transfer complex in human plasma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 77 (6): 3327–30. Bibcode:1980PNAS...77.3327F. doi:10.1073/pnas.77.6.3327. PMC 349608. PMID 6774335.

- Schindler PA, Settineri CA, Collet X, Fielding CJ, Burlingame AL (April 1995). "Site-specific detection and structural characterization of the glycosylation of human plasma proteins lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and apolipoprotein D using HPLC/electrospray mass spectrometry and sequential glycosidase digestion". Protein Science. 4 (4): 791–803. doi:10.1002/pro.5560040419. PMC 2143102. PMID 7613477.

- Yang CY, Gu ZW, Blanco-Vaca F, Gaskell SJ, Yang M, Massey JB, et al. (October 1994). "Structure of human apolipoprotein D: locations of the intermolecular and intramolecular disulfide links". Biochemistry. 33 (41): 12451–5. doi:10.1021/bi00207a011. PMID 7918467.

- Holzfeind P, Merschak P, Dieplinger H, Redl B (October 1995). "The human lacrimal gland synthesizes apolipoprotein D mRNA in addition to tear prealbumin mRNA, both species encoding members of the lipocalin superfamily". Experimental Eye Research. 61 (4): 495–500. doi:10.1016/S0014-4835(05)80145-9. PMID 8549691.

- Zeng C, Spielman AI, Vowels BR, Leyden JJ, Biemann K, Preti G (June 1996). "A human axillary odorant is carried by apolipoprotein D". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (13): 6626–30. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.6626Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6626. PMC 39076. PMID 8692868.

- Cargill M, Altshuler D, Ireland J, Sklar P, Ardlie K, Patil N, et al. (July 1999). "Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes". Nature Genetics. 22 (3): 231–8. doi:10.1038/10290. PMID 10391209. S2CID 195213008.

- Liu Z, Chang GQ, Leibowitz SF (May 2001). "Apolipoprotein D interacts with the long-form leptin receptor: a hypothalamic function in the control of energy homeostasis". FASEB Journal. 15 (7): 1329–31. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0530fje. PMID 11344130. S2CID 14390285.

- Sánchez D, Ganfornina MD, Martínez S (January 2002). "Expression pattern of the lipocalin apolipoprotein D during mouse embryogenesis". Mechanisms of Development. 110 (1–2): 225–9. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00578-0. hdl:10261/307861. PMID 11744388. S2CID 17460139.

- Mahadik SP, Khan MM, Evans DR, Parikh VV (November 2002). "Elevated plasma level of apolipoprotein D in schizophrenia and its treatment and outcome". Schizophrenia Research. 58 (1): 55–62. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00378-4. PMID 12363390. S2CID 22634600.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, et al. (December 2002). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Desai PP, Hendrie HC, Evans RM, Murrell JR, DeKosky ST, Kamboh MI (January 2003). "Genetic variation in apolipoprotein D affects the risk of Alzheimer disease in African-Americans". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 116B (1): 98–101. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10798. PMID 12497622. S2CID 25171300.

- Kang MK, Kameta A, Shin KH, Baluda MA, Kim HR, Park NH (July 2003). "Senescence-associated genes in normal human oral keratinocytes". Experimental Cell Research. 287 (2): 272–81. doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00061-2. PMID 12837283.

- Thomas EA, Laws SM, Sutcliffe JG, Harper C, Dean B, McClean C, et al. (July 2003). "Apolipoprotein D levels are elevated in prefrontal cortex of subjects with Alzheimer's disease: no relation to apolipoprotein E expression or genotype". Biological Psychiatry. 54 (2): 136–41. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01976-5. PMID 12873803. S2CID 46158571.

External links

[edit]- Apolipoproteins+D at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Applied Research on Apolipoproteins

- Human APOD genome location and APOD gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P05090 (Apolipoprotein D) at the PDBe-KB.