Armenian cultural heritage in Turkey

| Armenian... | 1914 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| population | 1,914,620[1] | 60,000[2] |

| churches and monasteries | 2,538[1] | 34 (functioning only)[3] |

| schools | 1,996[1] | 18[3] |

The eastern part of the current territory of the Republic of Turkey is part of the ancestral homeland of the Armenians.[4] Along with the Armenian population, during and after the Armenian genocide the Armenian cultural heritage was targeted for destruction by the Ottoman government. Of the several thousand churches and monasteries (usually estimated from two to three thousand) in the Ottoman Empire in 1914, today only a few hundred are still standing in some form; most of these are in danger of collapse. Those that continue to function are mainly in Istanbul.

Most of the properties formerly belonging to Armenians were confiscated by the Turkish government and turned into military posts, hospitals, schools and prisons. Many of these were also given to Muslim migrants or refugees who had fled from their homelands during the Balkan Wars. The legal justification for the seizures was the law of Emval-i Metruke (Law of Abandoned Properties), which legalized the confiscation of Armenian property if the owner did not return.[5]

Language, literature, education

[edit]Schools

[edit]Armenian schools were not allowed in Ottoman Empire until the late 18th century. Unofficially, a number of schools existed in the Bitlis region, but the first school "in real terms" was opened in 1790 by Shnork Migirdic and Amira Miricanyan. During Patriarch Garabet's reign from 1823 to 1831, Armenian schools were established at unprecedented levels. The first higher education institution was opened in 1838 in Uskudar and was named Cemeran School. By 1838, according to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, 439 Armenian schools operated in Anatolia.[6] By the time of the proclamation of the Tanzimat era by Sultan Abdülmecid I in 1839, the Armenians had some thirty-seven schools, including two colleges, with 4,620 students; several museums, printing presses, hospitals, public libraries and eight different published journals in Constantinople alone.[7] According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople there were 803 Armenian schools in the Ottoman Empire with 81,226 students and 2,088 teachers in 1901–1902. Of these 438 schools were in the Six vilayets with 36,839 students and 897 teachers.[8] During the Armenian genocide, the Armenian population of the empire was targeted a mass extermination. Most schools in Anatolia were destroyed or were set to be used for other purposes. As of 2005, 18 Armenian schools were functioning in Istanbul.[9]

Literature

[edit]Notable writers from this period include Siamanto, Hagop Baronian, Vahan Tekeyan, Levon Shant, Krikor Zohrab, Rupen Zartarian, Avetis Aharonyan, Atrpet, and Gostan Zarian.

The 19th century beheld a great literary movement that was to give rise to modern Armenian literature. This period of time during which Armenian culture flourished is known as the Revival period (Zartonk). The Revivalist authors of Constantinople and Tiflis, almost identical to the Romanticists of Europe, were interested in encouraging Armenian nationalism. Most of them adopted the newly created Eastern or Western variants of the Armenian language depending on the targeted audience, and preferred them over classical Armenian (grabar).

The Revivalist period ended in 1885–1890, when the Armenian people was passing tumultuous times. Notable events were the Berlin Treaty of 1878, the independence of Balkan nations such as Bulgaria, and of course, the Hamidian massacres of 1895–1896.

Dialects

[edit]Press

[edit]

Some specialists claim that the Armenian Realist authors appeared when the Arevelk (Orient) newspaper was founded (1884). Writers such as Arpiar Arpiarian, Levon Pashalian, Krikor Zohrab, Melkon Gurjian, Dikran Gamsarian, and others revolved around the said newspaper. The other important newspaper at that time was the Hayrenik (Fatherland) newspaper, which became very populist, encouraged criticism, etc.

Today, three dailies (Agos, Jamanak and Marmara) are published in Istanbul.

Alphabet

[edit]As Bedross Der Matossian from Columbia University describes, for about 250 years, from the early 18th century until around 1950, more than 2000 books in the Turkish language were printed using the Armenian script. Not only did Armenians read Armeno-Turkish, but so did the non-Armenian (including the Ottoman Turkish) elite. The Armenian script was also used alongside the Arabic script on official documents of the Ottoman Empire written in Ottoman Turkish. For instance, the first novel to be written in the Ottoman Empire was Vartan Pasha's 1851 Akabi Hikayesi, written in the Armenian script. Also, when the Armenian Duzian family managed the Ottoman mint during the reign of Abdülmecid I, they kept records in Armenian script, but in the Turkish language.[10] From the end of the 19th-century, the Armenian alphabet was also used for books written in the Kurdish language in the Ottoman Empire.

Armenian place names

[edit]Initial renaming of Armenian place names were formally introduced under the reign of Sultan Abdulhamit II. In 1880, the word Armenia was banned from use in the press, schoolbooks, and governmental establishments, and was subsequently replaced with words like Anatolia or Kurdistan.[11][12][13][14][15] Armenian name changing continued under the early Republican era up until the 21st century. It included the Turkification of last names, change of animal names,[16] change of the names of Armenian historical figures (i.e. the name of the prominent Balyan family was concealed under the identity of a superficial Italian family called Baliani),[17][18] and the change and distortion of Armenian historical events.[19]

Most Armenian geographical names were in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Villages, settlements, or towns that contain the suffix -kert, meaning built or built by (i.e. Manavazkert (today Malazgirt), Norakert, Dikranagert, Noyakert), -shen, meaning village (i.e. Aratashen, Pemzashen, Norashen), and -van, meaning town (i.e. Charentsavan, Nakhichevan, Tatvan), indicate an Armenian name.[20] Throughout Ottoman history, Turkish and Kurdish tribesmen have settled into Armenian villages and changed the native Armenian names (i.e. the Armenian Norashen was changed to Norşin). This was especially true after the Armenian genocide, when much of eastern Turkey was depopulated of its Armenian population.[20]

It is estimated by etymologist and author Sevan Nişanyan that 3600 Armenian geographical location names have been changed.[21]

Religious buildings

[edit]Overview

[edit]In 1914, the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople compiled a list of monasteries, churches and other religious institutions throughout the Ottoman Empire. The Patriarchate revealed that 2,549 religious sites under the control of the Patriarch which included more than 200 monasteries and 1,600 churches.[22][23]

In 2011, there were 34 Armenian churches functioning in Turkey, mostly in Istanbul.[3]

List of notable churches, monasteries

[edit]| Early 20th century image with description | Current status with image today | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Holy Apostles Monastery Սուրբ Առաքելոց վանք | |||

|

One of the double doors of the Monastery (dated 1134) was discovered in Bitlis and had it taken to Tbilisi for safekeeping.[24] The door was later taken to Yerevan in 1925 where is displayed at the History Museum of Armenia.[24] | ||

| Saint Karapet Monastery Մշո Սուրբ Կարապետ վանք | |||

The Saint Karapet Monastery was an Armenian monastic complex in the Taron Province of Greater Armenia, about 35 kilometers northwest of Mush, now in the Kurdish village of Chengeli in eastern Turkey. Founded in the fourth century by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, it was one of the oldest monasteries in Armenia.Saint Karapet Monastery was also one of the three most important sites for Armenian Christian pilgrimage, and among the richest, most ancient institutions in Ottoman Armenia. |

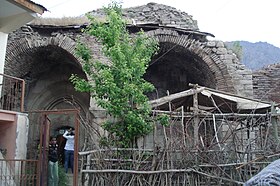

After the Armenian genocide, it was destroyed to its foundations. It was blown up by the Turkish army several times. Today what remains of Surb Karapet consists of a few shapeless ruins and carved stones and khachkars which have been used as building materials by the current Muslim residents, mostly Kurds, and are often found encrusted in the walls of local homes and structures. | ||

| Varagavank Վարագավանք | |||

Founded in the early 11th-century on a pre-existing religious site, it was one of the richest and best known monastery's in the Armenian kingdom of Vaspurakan and in later centuries, was the seat of the archbishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Van.[25] It was founded by King Senekerim-Hovhannes of the Artsruni Dynasty early in his reign (1003–24) to house a relic of the True Cross that had been kept in a 7th-century hermitage on the same site. The interior form of the central church resembles the designs of the Saint Hripsime church in Armenia.[26] The Armenian archbishops of Van resided here until the late 19th century. Of them, the future Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian "Hayrik" (Father), founded Artsiv Vaspurakani (The Eagle of Vaspurakan), the first newspaper to be printed in historical Armenia.[27] |

During the Armenian genocide, on 30 April 1915, the Ottoman army destroyed the monastery during the Siege of Van. Its ruins are still visible in the Kurdish-populated village of Bakraçlı that later developed on the same site. The Monastery is now used as hay storage for domesticated animals. | ||

| Narekavank Նարեկավանք | |||

The 10th century Armenian monastery of Narekavank, Lake Van, Vaspurakan (modern Turkey). Early 20th century. |

Completely destroyed The monastery ceased to function in 1915, during the Armenian genocide, and was demolished in 1951. The Kurdish-populated village of Yemişlik grew up on the site, and a mosque now stands where the monastery once stood.[28][29] | ||

| Saint Bartholomew Monastery Սուրբ Բարդուղիմեոսի վանք | |||

The Saint Bartholomew Monastery was built in the 13th century in what was then the Vaspurakan Province of Greater Armenia, now near the town of Başkale (Albayrak) in the Van Province of southeastern Turkey. It was formerly considered one of the most important pilgrimage sites of the Armenian people.[30] The monastery was built on the traditional site of the martyrdom of the Apostle Bartholomew[30] who is reputed to have brought Christianity to Armenia in the 1st century. Along with Saint Thaddeus, Saint Bartholomew is considered the patron saint of the Armenian Apostolic Church. |

At an unknown date after the Armenian genocide, the monastery was subjugated under the control of the Turkish military and its entire site now lies within the compound of an army base and its access is restricted. The dome of its church was still intact in the early 1960s, but the whole structure is now very heavily ruined and the dome is entirely gone. | ||

The Armenian Monastery on the island was called St. George or Sourp Kevork.[31] It was built in 1305 and expanded in 1621 and 1766.[31] |

During the Armenian genocide an upwards of 12,000 Armenian women and children, crossed to the isle over a period of three days while a few dozen men covered their retreat from Hamidiye regiments. All starved to death before help could arrive.[32] The Monastery is currently in ruins.[31] | ||

| Sourb Nshan of Sebastia Սուրբ Նշան վանք | |||

Sourb Nshan monastery was established by prince Atom-Ashot, the son of King Senekerim. The monastery was named after a celebrated relic that Senekerim had brought from Varagavank monastery, and which was returned there after his death. This was one of notable center of enlightenment and scholarship of Lesser Armenia during Byzantine, Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and Ottoman reigns until the Armenian genocide in 1915. In 1915 Sourb Nshan monastery was the main repository of medieval Armenian manuscripts in the Sebastia region and at least 283 manuscripts are recorded. The library was not destroyed during World War I and most of the manuscripts survived. In 1918 about 100 of them were transferred to the Armenian Patriarchate in Jerusalem. |

In 1978, the monastery was demolished with explosives. A military base now occupies the site. No traces of the Monastery remain. | ||

| Ktuts monastery Կտուց | |||

Ktuts monastery, meaning beak in Armenian, is an abandoned 15th century Armenian monastery on the small island of Ktuts (Çarpanak) in Lake Van, Vaspurakan (present-day Turkey).[33] The Ktuts Monastery is situated on a small island in the middle of lake Van, Turkey. |

Nowadays, Ktuts monastery appears to be in a better condition than most Armenian monasteries, possibly due to its location. However, there is still overgrowth on the roof due to the fact the monastery has not been maintained since 1915. | ||

Holy Apostles Church

Սուրբ Առաքելոց եկեղեցի | |||

Located in the city of Kars, the Holy Apostles Church completed construction in the 940s during Bagratid Armenia under the rule of Abas I. The Church was called the Holy Apostles Church due to the sculptures of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus located in the exterior of the Church. In 1064 to the 1100s (decade), the Church was converted into a Mosque when it was captured by the Seljuks. Under the Ottoman Empire, the Church was once again converted into a Mosque (1579–1877). After the Russian capture of Kars in 1877 it was converted to a Russian Orthodox church. In 1918, after the fall of Kars to the Turkish army, the cathedral was again turned into a mosque. In 1919, following the retreat of Turks and during the first republic of Armenia, the cathedral was restored as an Armenian church. In 1920, Kars again fell to Turkey and it ceased to function as a church. It operated briefly as a mosque in the 1920s before being used as a petrol storage depot. It functioned as the Kars Museum between 1969 and 1980. |

The church was confiscated and became the property of the Turkish state. It has been sold to the local municipality, who planned to demolish it and build a school on the site. The plan never took hold. However, during this time, its bell tower was destroyed. In the 1950s it was used as a depot for petroleum. During the 1960s and 1970s it housed a small museum. The church is currently used as a mosque. | ||

Holy Cross of Aghtamar

Սուրբ Խաչ | |||

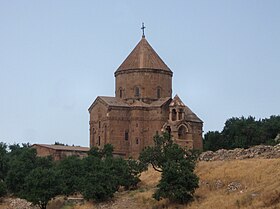

It was ordered to be built by King Gagik I Artsruni during the years 915–921. It was built of pink volcanic tufa by the architect-monk Manuel with an interior measuring 14.80m by 11.5m and the dome reaching 20.40m above ground. The architecture of the church is based on a form that had been developed in Armenia several centuries earlier; the best-known example being that of the seventh century St. Hripsime church in Echmiadzin.[34] During his reign, King Gagik I Artsruni (r. 908-943/944) of the Armenian kingdom of Vaspurakan chose the island of Aghtamar as one of his residences, founding a settlement there.[34] Between 1116 and 1895 Aght'amar Island was the location of the Armenian Catholicosate of Aghtamar. |

During the Armenian genocide, the monks of Aghtamar were massacred, the church looted, and the monastic buildings destroyed. The church remained disused through the decades after 1915.[35] After the 1920s, the church was exposed to extensive vandalism. The ornate stone balustrade of the royal gallery disappeared, and comparisons with pre-1914 photographs show cases of damage to the relief carvings. The khatchkar of Catholicos Stephanos, dated 1340, was, by 1956, badly mutilated with large sections of its carvings hacked off. In 1956 only the bottom third of another ornate khachkar, dated 1444, was left – it was intact when photographed by Bachmann in 1911. The 19th-century tombstone of Khatchatur Mokatsi, still intact in 1956, was later smashed into fragments.[36] "In the 1950s the island was used as a military training ground."[37][38] In 2005 the structure was closed to visitors as it underwent a heavy restoration, being opened as a museum by the Turkish government a year later.[39] | ||

| Cathedral of Arapgir Արաբկիրի մայր եկեղեցի | |||

The Cathedral of Arapgir named Holy Mother of God was built in the 13th century. It was one of the biggest churches in Western Armenia. It was able to house 3,000 people. The cathedral was attacked and looted and burnt in 1915 during the Armenian genocide. |

Completely destroyed After the Armenian genocide the cathedral was repaired and was used as a school. In 1950 the Municipality of Arapgir decided to demolish the cathedral. On 18 September 1957 the cathedral was blown up with dynamite. And later, the land where the cathedral stood was sold to a peasant named Hüseyin for 28,005 lira.[40] Today, in place of the cathedral are ruins. | ||

| Khtzkonk Monastery Խծկոնք վանք | |||

The Khtzkonk Monasteries were a monastic ensemble of five Armenian churches built between the 7th and 13th centuries in what was then the Armenian Bagratid kingdom of Ani. It is now near the town of Digor, the administrative capital of the Digor district of the Kars Province in Turkey, about 19 kilometres west of the border with Armenia. The monastery is located in a gorge formed by the Digor River. |

In 1959 the French art historian J. M. Thierry visited the site and found that four of the five churches had been destroyed, with only the Church of Saint Sargis surviving in a badly damaged condition.[41] According to local people, the churches were blown up by the Turkish army using high explosives, which was reaffirmed by citizens of Digor in 2002.[42] Their information is confirmed by the physical evidence on the site. The dome of the surviving church is intact but the side walls have been blown outwards; the destroyed churches have been entirely leveled with their masonry blasted into the gorge below. This is damage that cannot have occurred as a result of an earthquake, historian William Dalrymple remarked.[43] | ||

Church of the Redeemer

Սուրբ Փրկիչ | |||

This church was completed shortly after the year 1035. It had a unique design: 19-sided externally, 8-apsed internally, with a huge central dome set upon a tall drum. It was built by Prince Ablgharib Pahlavid to house a fragment of the True Cross. |

The church was largely intact until 1955, when the entire eastern half collapsed during a storm.[44] |

||

See also

[edit]- Armenians in Turkey

- Armenian genocide

- Armenian culture

- Confiscated Armenian properties in Turkey

- Anti-Armenian sentiment in Turkey

- Khachkars of the Armenian cemetery in Julfa

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kévorkian, Raymond H. (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: I. B. Tauris. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-84885-561-8. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 15 December 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Bedrosyan, Raffi (1 August 2011). "Bedrosyan: Searching for Lost Armenian Churches and Schools in Turkey". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian A. Skoggard (2004). Encyclopedia of diasporas: immigrant and refugee cultures around the world. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9.

Currently, only one-sixth of that land [ancestral territory] is inhabited by Armenians, due first to variously coerced emigrations and finally to the genocide of the Armenian inhabitants of the Ottoman Turkish Empire in 1915.

- ^ Biner, Z. Ö. (2010). Acts of defacement, memory of loss: Ghostly effects of the "Armenian crisis" in Mardin, southeastern Turkey. History and Memory, 22(2), 68–94, 178.

- ^ Gökçe, Feyyat (Summer 2010). "Minority and Foreign Schools on the Ottoman Education System". E-International Journal of Educational Research. 1 (1): 44–45. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Oshagan, Vahe (2004). Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). The Armenian people from ancient to modern times (1st paperback ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-4039-6422-9.

- ^ James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce, The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915–16 Archived 11 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, London, T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., 1916, pp. 662–64

- ^ "Armenian Claims and Historical Facts: Questions and Answers" (PDF). Ankara: Turkish Ministry of Tourism, Center for Strategic Research. 2005. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

The Armenian community in Istanbul has 18 schools, 17 cultural and social organizations, three daily newspapers, five periodicals, two sports clubs, 57 churches, 58 foundations and two hospitals.

- ^ Mansel, Philip (2011). Constantinople. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-84854-647-9. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ (in Russian) Modern History of Armenia in the Works of Foreign Authors [Novaya istoriya Armenii v trudax sovremennix zarubezhnix avtorov], edited by R. Sahakyan, Yerevan, 1993, p. 15

- ^ Boar, Roger; Blundell, Nigel (1991). Crooks, crime and corruption. New York: Dorset Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-88029-615-1.

- ^ Balakian, Peter (13 October 2009). The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. HarperCollins. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-06-186017-1.

- ^ Books, the editors of Time-Life (1989). The World in arms : timeframe AD 1900–1925 (US ed.). Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8094-6470-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ K. Al-Rawi, Ahmed (2012). Media Practice in Iraq. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-230-35452-4. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Turkey renames 'divisive' animals". BBC. 8 March 2005. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

Animal name changes: Red fox known as Vulpes Vulpes Kurdistanica becomes Vulpes Vulpes. Wild sheep called Ovis Armeniana becomes Ovis Orientalis Anatolicus. Roe deer known as Capreolus Capreolus Armenus becomes Capreolus Cuprelus Capreolus.

- ^ "Yiğidi öldürmek ama hakkını da vermek..." Lraper (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "Patrik II. Mesrob Hazretleri 6 Agustos 2006 Pazar". Bolsohays News (in Turkish). 7 August 2006. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G., ed. (1991). The Armenian genocide in perspective (4th ed.). New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Transaction. pp. 128–30. ISBN 978-0-88738-636-7.

- ^ a b Sahakyan, Lusine (2010). Turkification of the Toponyms in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey (PDF). Montreal: Arod Books. ISBN 978-0-9699879-7-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Nisanyan, Sevan (2011). Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul: TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Bevan, Robert (2004). The destruction of memory : architectural and cultural warfare (1st ed.). London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-205-5. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Cultural Genocide". Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Surp Arakelots Vank – The Holy Apostles Monastery". VirtualAni. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Varagavank' Monastery". Rensselaer Digital Collections. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- ^ Armenia, Travels and Studies. Volume 2. The Turkish Provinces By Harry Finnis Blosse Lynch – Page 114

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2000), "Van in This World; Paradise in the Next: The Historical Geography of Van/Vaspurakan", in Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.), Armenian Van/Vaspurakan, Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, p. 28, OCLC 44774992

- ^ Suciyan, Talin (7 April 2007). "Holy Cross survives, diplomacy dies" (PDF). The Armenian Reporter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ Papazian, Iris (19 July 1997). "Archbishop Mesrob Ashjian on a Sentimental Journey to Western Armenia". Armenian Reporter International. p. 18.

The group also visited the village of Narek, now desolate. The image of a mosque on the very spot where once stood the famed Narek Monastery caused great sorrow.

- ^ a b "The Condition of the Armenian Historical Monuments in Turkey". Research on Armenian Architecture. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ a b c "A Pilgrimage to Lake Van" (PDF). EasternTurkeyTours. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: I.B. Taurus and Co. Ltd. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-84885-561-8.

- ^ "Ktuts' Anapat". Rensselaer Digital Collections. Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- ^ a b (in Armenian) Harutyunyan, Varazdat M. "Ճարտարապետություն" ("Architecture"). History of the Armenian People. vol. iii. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976, pp. 381–84.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Sirape Der Nersessian Aght'amar Church of the Holy Cross, 1964, pp. 7, 49–52.

- ^ (in Turkish) "Paylaşılan Bir Restorasyon Süreci: Akhtamar Surp Haç Kilisesi Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine." Mimarizm. 26 February 2008.

- ^ "Restoration Process". Bianet.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Asbarez, 1 October 2010: The Mass at Akhtamar, and What's Next". Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Antarnik L. Pladian, 1969, New York – Arapkir Union, p. 931

- ^ (in French) Thierry, Jean-Michel, "Notes Sur des Monuments Armeniens en Turque (1964)," Revue des Études Arméniennes, volume 2, 1965.

- ^ Hofmann, Tessa. Armenians in Turkey Today: A Critical Assessment of the Situation of the Armenian minority in the Turkish Republic (2002), 40.

- ^ Dalrymple, William, "Armenia's Other Tragedy," The Independent Magazine, 18 March 1989.

- ^ Sim, Steven. "The church of the Redeemer". VirtualANI. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2007.