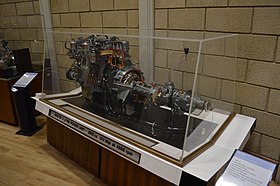

BMC C-Series engine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

| BMC C-Series Engine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | British Motor Corporation |

| Production | 1954 - 1971 |

| Layout | |

| Configuration | OHV Inline-6 |

| Displacement | 2.6 L; 161.0 cu in (2,639 cc) 2.9 L; 177.7 cu in (2,912 cc) |

| Cylinder bore | 79.4 mm (3.13 in) (2.6 L) 83.4 mm (3.28 in) (2.9 L) |

| Piston stroke | 88.9 mm (3.50 in) |

| Cylinder block material | Cast Iron |

| Cylinder head material | Cast Iron |

| Valvetrain | OHV, Duplex Chain drive |

| Combustion | |

| Fuel system | 1, 2 or 3 Carburettor(s) |

| Fuel type | Petrol |

| Cooling system | Water-cooled |

| Output | |

| Power output | 63 kW (86 PS; 84 hp)→76 kW (103 PS; 102 hp) (2.6 L) 76 kW (103 PS; 102 hp)→112 kW (152 PS; 150 hp) (2.9 L) |

| Dimensions | |

| Dry weight | 1954-1967: 271 kg (597 lb) 1967-1971: 251 kg (553 lb)[1] |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Austin D-Series engine |

| Successor | BMC E-Series engine |

The BMC C-Series is a straight-6 automobile engine produced from 1954 to 1971. Unlike the Austin-designed A-Series and B-Series engines, it came from the Morris Engines drawing office in Coventry and therefore differed significantly in its layout and design from the two other designs which were closely related. This was due to the C-Series being in essence an enlarged overhead valve development of the earlier 2.2 L Straight-6 overhead camshaft engine [2] used in the post-war Morris Six MS and Wolseley 6/80 from 1948 until 1954, which itself also formed the basis of a related 1.5 L 4-cylinder engine for the Morris Oxford MO in side-valve form and the Wolseley 4/50 in overhead camshaft form. Displacement was 2.6 to 2.9 L with an undersquare stroke of 88.9 mm (3.50 in), bored out to increase capacity.

Mission

[edit]The revised engine was required to replace BMC's inherited diverse collection of 2+1⁄2-litre (150 cu in) engines made to prewar designs and Austin's wartime designed four-cylinder BS1. A long-stroke engine, though closer to square than BMC contemporaries, with a cast iron block and cylinder head using Weslake patents, its overhead valves were operated by pushrods. Previously, Rileys used high-mounted twin camshafts with short pushrods, and Wolseleys used single overhead camshafts. The twin-cam Riley and OHC Wolseley engines were expensive to make, sold in low volumes and both had had reliability problems, especially with overheating valves under sustained high loads. The brief for the C-Series was to be a more conventional design that was easy to build and service, more refined than the existing big Austin four-cylinder power units and with an emphasis on reliability and a long service life. At the design stage high performance was not foreseen as BMC had no sporting models of a size requiring an engine like the C-Series.[citation needed]

The biggest design difference between the Morris-designed C-Series and the Austin-penned A- and B-Series engines was the position of the camshaft - on the right-hand side of the block (as viewed from within the car) rather than the left, although all three engines had their inlet and exhaust ports on the left. This meant that the C-Series didn't require the compound ports of the Austin engines, which were partly required to provide space in the cylinder head for the pushrods. This should, theoretically, have provided the C-Series with superior 'breathing' and efficiency than the smaller engines since it still used the same highly-effective heart-shaped Combustion chamber design by Harry Weslake. However this was undermined by the carburettor arrangements; instead of a dedicated intake manifold the C-Series was designed with an intake gallery cast into the cylinder head, with the carburettor(s) attached directly to the intake(s). This design was chosen for ease of construction and to allow different carburettor arrangements to be easily accommodated and the design also eliminated carburettor icing. Each cylinder had a generous-sized intake port from the gallery but the restrictive shape of the gallery and the carburettor port(s) severely limited the engine's maximum power output and speed, as did the four-bearing crankshaft. There appear to have been plans for a twin cam variant of the C-Series, using the same basic head and valve design as the DOHC B-Series in the MGA Twin Cam for use in Rileys and Wolseleys. This explains the relatively unadventurous design of the standard engine. However the reliability problems of the twin-cam B-Series and the mixed reception of the Riley Pathfinder discouraged BMC from pursuing this development and work stopped in 1955.[citation needed]

Other signs of the Morris origins of the design were the crankcase being cast with strengthening ribs (a feature not introduced to the A-Series until 1980) and the big end bearings being split diagonally rather than horizontally. The C-Series also had a hydraulic tensioning unit for its timing chain and had the oil pump and distributor driven via separate sets of skew-cut gears on the camshaft. This was relatively unusual for mass-produced engines of the time; the A- and B-Series engines, and most of their contemporaries, had both oil pump and distributor driven by one shaft driven from one skew gear. The C-Series' arrangement reduced load on the gears and therefore wear, preventing the ignition timing falling out of specification over time.[citation needed]

Given the design emphasis on durability and ease of manufacture, the C-Series has always been considered an engine that was both large and heavy for its capacity and power output, initially proving to have little benefit, aside from the greater refinement of six-cylinders, over the Austin-designed four-cylinder 2.6-litre BS1 engine installed in the Austin A90 Atlantic and Austin-Healey 100. Austin's engineers attributed this to the poor cylinder head design. In 1957 the Healey was given a twelve-port head with a conventional intake manifold, increasing output by 15 bhp (11 kW) or fifteen per cent. In 1959 carburettors were revised and replaced. In 1961 the inlet tract was improved, exhaust timing was adjusted, and twin exhausts added. Later in 1961 the saloon engines were slightly detuned and the Healey version's performance upgraded, probably by Weslake. Then the Austin Healey Mark III was announced.[citation needed]

The C-Series was also less efficient than, and in engineering terms was a retrograde step from Nuffield's engines: the Riley-designed Riley 2½-litre Big Four twin-cam four-cylinder unit fitted in the Riley RM series, and Riley's prewar cars, and the Wolseley designed Wolseley 2.2-litre straight six with a single overhead camshaft used in the Morris Six MS version of the Wolseley 6/80 which dated back to the early 1920s.

The Austin BS1 had begun as a late wartime Rix and Bareham design, two-thirds of a Bedford-based wartime truck engine known as the Austin D-Series, for a 2.2-litre ohv unit intended for a British jeep which became the civilian Austin Champ. Its use spread to Austin's Sixteen, their light commercial vehicles and the FX3 taxi.[3]

However the C-Series was much more reliable than these units and cheaper to manufacture.

Version 1

[edit]Applications 1

[edit]- 2.6 L (2,639 cc) (announced 18 October 1954)[4]

- 1954-1959 26A Austin A90 Westminster[5] - 85 bhp (63 kW)

- 1956-1959 26A Austin A95 Westminster - 68 kW (91 bhp)

- 1956-1959 26A Austin A105 Westminster - 76 kW (102 bhp)

- 1956-1959 26AH Austin-Healey 100-6 - 76 kW (102 bhp) → 87 kW (117 bhp)

- 1955-1956 26M Morris Isis Series I - 86 bhp (64 kW)

- 1956-1958 26M Morris Isis Series II - 90 bhp (67 kW)

- 1957-1959 26M Morris Marshal - 63 kW (84 bhp)

- 1958-1959 26R Riley Two-Point-Six - 95 bhp (71 kW) → 101 bhp (75 kW)

- 1954-1959 26W Wolseley 6/90[6] - 95 bhp (71 kW)

Applications 2

[edit]

- 2.9 L (2,912 cc) - Four bearing crankshaft (announced 17 July 1959)[7]

- 1959-1961 29A Austin A99 Westminster[8] - 103–108 bhp (77–81 kW)

- 1961-1968 29A Austin A110 Westminster - 120 bhp (89 kW)

- 1959-1967 29AH Austin-Healey 3000 - 136–150 bhp (101–112 kW)

- 1959-1961 29VA Vanden Plas Princess 3-Litre - 103–108 bhp (77–81 kW)

- 1961-1964 29VB Vanden Plas Princess 3-Litre - 120 bhp (89 kW)

- 1959-1961 29WA Wolseley 6/99[9] - 102 bhp net (76 kW), 112 bhp gross (84 kW)

- 1961-1968 29WB Wolseley 6/110 - 120 bhp (89 kW) at 4850 rpm; a low compression version producing 115 bhp (86 kW) at 4750 rpm was offered for certain export markets

Revision

[edit]With the car market demanding ever-increasing power and performance in the 1960s, especially from sports cars such as the Austin-Healeys BMC engineers concluded that the existing C-Series with four main bearings could not reliably withstand more than 150 bhp (112 kW; 152 PS) in road use and 170 bhp (127 kW; 172 PS) for short periods in competition. The four-bearing engine was also limited as to its maximum rotational speed due to the relative lack of crankshaft support.

With demand for the Austin-Healey 3000 still strong and development of what would become the Austin 3-Litre underway BMC carried out a thorough redesign of the C-Series with the aim of improving the power output and reducing both the engine's weight and its overall size. The engine was reworked to carry seven main bearings (each reduced in width compared to those in the four-bearing version), steel ancillary castings were swapped for aluminium alloy ones where possible. The main block and cylinder head castings were extensively redesigned while retaining the same cylinder capacity of 2.9 L (2,912 cc) - the bores were now evenly spaced and had coolant gallery between all six bores while the original C-Series featured three pairs of 'siamesed' bores without coolant between the bores in each pair. Similarly, the new cylinder head had the Weslake combustion chambers located symmetrically and centralised on each bore, instead of being offset to the exhaust side as on the original engine. While both these changes, and the increased number of bearings, added to the overall volume taken up by the engine's main internal parts, the outer coolant galleries of the block were made slimmer and the main castings themselves were thinner, so the redesigned engine was actually 1.75 inches (4.45cm) shorter in overall length than the older version. The manifolds were altered for more efficient 'breathing', especially at high engine speeds.

BMC aimed for a 30 per cent weight reduction at 175 lb (79 kg) and a maximum reliable power output in competition tune of around 200 bhp (149 kW; 203 PS). In the event a minimal weight saving was returned - the revised engine was only 45 lb (20 kg) lighter than the old version. The main identifying feature of the 'mark 2' C-Series engine is the much narrower Rocker cover, which is only around half the width of the cylinder head, whereas the original engine has nearly full-width cover.

By the time the new engine was available the Austin-Healey 3000 had been dropped and was replaced by the MGC. No real use was made of the revised engine's greater strength and the power outputs were broadly similar to the original 2.9-litre engine at 145 bhp (108 kW; 147 PS). This was slightly less than the maximum output achieved by the older engine in the Austin-Healey 3000, the decrease being blamed on the greater internal friction due to the greater number of main bearings coupled to the same carburation and tuning being carried over from the original engine.

Applications 3

[edit]- 2.9 L (2,912 cc) - Seven bearing crankshaft

- 1967-1971 29AA Austin 3-Litre - 93 kW (126 PS; 125 hp)

- 1967-1970 29GA MGC - 108 kW (147 PS; 145 hp)

Racing engines

[edit]Much of the potential in the revised C-Series was demonstrated by the six specialised racing versions of the MGC built for 12 Hours of Sebring races in 1968 and 1969. These cars, dubbed the MGC GTS, used special versions of the C-Series engine. The first car was built with an engine where both the head and the block were cast in aluminium alloy but this proved troublesome and all the cars eventually used the standard iron block with an alloy head. The head had a higher compression ratio, larger valves (from the Ford Essex V6), revised porting and redesigned exhaust system as well as using triple twin-choke Weber carburetors. These specialised versions of the C-Series made an easy and reliable 200 bhp (149 kW; 203 PS) with a weight loss similar that hoped for in the redesign process. However the inherent cost of these engines and the commercial failure of both the MGC and the Austin 3-Litre meant that none of these alterations were considered for the production units.

End of run

[edit]As an all-iron, overhead-valve engine, the C-Series was becoming outdated in terms of its construction and power-to-weight ratio. These factors were significant contributors to the poor sales performance of the last two cars it was installed in. It was effectively replaced, after a short hiatus, by 2.2 and 2.6-litre straight-six versions of the E-Series engine, introduced in 1972. The E-Series provided larger capacity six-cylinder engines made on the same tooling as the four-cylinders.

References

[edit]- ^ "Engines : C-Series - AROnline". 26 August 2011.

- ^ Pressnell, Jon (2013). Morris: The Cars and the Company. United Kingdom: J H Haynes & Co Ltd. p. 227. ISBN 978-1859609965.

- ^ Time for Sixteens to come of age. Martyn Nutland. Austin Times, April 2003, Volume 1, Issue 1.

- ^ New Austin Car. The Times, Tuesday, 19 Oct 1954; pg. 4; Issue 53066

- ^ New Austin Car. The Times, Tuesday, 19 Oct 1954; pg. 4; Issue 53066

- ^ New Wolseley Car. The Times, Wednesday, 20 Oct 1954; pg. 5; Issue 53067

- ^ New Austin Model. The Times, Friday, 17 Jul 1959; pg. 3; Issue 545156

- ^ Fine Road Performance of the Austin A.99. The Times, Tuesday, 8 Mar 1960; pg. 15; Issue 54714

- ^ Farina-Styled Car By Wolseley. The Times, Wednesday, 8 Jul 1959; pg. 4; Issue 54507