Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf

| Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

The memorial at Hartmannswillerkopf. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Louis de Maud'huy | Hans Gaede | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Seventh Army | Armee-Abteilung Gaede | ||||||

The Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf (French: bataille du Vieil-Armand) was a series of engagements during the First World War fought for the control of the Hartmannswillerkopf peak in Alsace in 1914 and 1915. The peak is a pyramidal rocky spur in the Vosges mountains, about 5 km (3.1 mi) north of Thann, standing at 956 m (3,136 ft) and overlooking the Alsace Plain, Rhine valley and the Black Forest in Germany. Hartmanswillerkopf was captured by the French army during the Battle of Mulhouse (7–10, 14–26 August 1914). From the vantage point, Mulhouse and the Mulhouse–Colmar railway could be seen and the French railway from Thann to Cernay and Belfort shielded from German observation.

The two French invasions and captures of Mulhouse by the French VII Corps (Général Louis Bonneau) and then the Army of Alsace (General Paul Pau), were repulsed by the German 7th Army (Generaloberst Josias von Heeringen). Both sides then stripped the forces in Alsace to reinforce the armies fighting on the Marne, Aisne and further north. For the rest of 1914 and 1915, both sides made intermittent attempts to capture Hartmanswillerkopf. The operations were costly and eventually after another period of attack and counter-attack that lasted into the new year of 1916, both sides accepted a stalemate, with a fairly stable front line along the western slopes that lasted until 1918.

Background

[edit]A few border skirmishes took place after Germany declared war on France; after 5 August, more German patrols were sent out as French attacks increased. French troops advanced from Gérardmer to the Col de la Schlucht (Schlucht Pass), where the Germans retreated and blew up the tunnel.[1] The French VII Corps (Général Louis Bonneau) comprising the 14th and 41st divisions, advanced from Belfort to Mulhouse and Colmar 35 km (22 mi) to the north-east, suffered supply difficulties but seized the border town of Altkirch, 15 km (9.3 mi) south of Mulhouse, with a bayonet charge.[2] On 8 August, Bonneau cautiously continued the advance and occupied Mulhouse, shortly after its German defenders had left. In the early morning of 9 August, parts of the XIV and XV Corps of the German 7th Army arrived from Strasbourg and counter-attacked at Cernay; Mulhouse was liberated by German troops on 10 August and Bonneau withdrew towards Belfort.[3]

Général Paul Pau was put in command of a new Armée d'Alsace to re-invade Alsace on 14 August, as part of a larger offensive by the First Army and the Second Army into Lorraine. The Armée d'Alsace began the new offensive against four German Landwehr brigades, which fought a delaying action as the French advanced from Belfort, two divisions on the right passing through Dannemarie at the head of the valley of the Ill river. On the left flank, two divisions advanced with several Chasseur battalions, which had moved into the Fecht valley on 12 August. On the evening of 14 August, Thann was captured and the most advanced French troops reached the western outskirts of the city by 16 August. On 18 August, VII Corps attacked Mulhouse and captured Altkirch on the south-eastern flank.[4] By the evening of 19 August, the French had occupied the city, having captured 24 guns, 3,000 prisoners and considerable amounts of equipment.[4] With the capture of the Rhine bridges and valleys leading into the plain, the French had gained control of Upper Alsace but on 26 August the French withdrew from Mulhouse to a more defensible line near Altkirch, to provide reinforcements for the French armies closer to Paris.[5]

Prelude

[edit]The Armée d'Alsace was dissolved on 26 August and many of its units distributed among the remaining French armies.[6] In September 1914, the German 7th Army was transferred to the Aisne and left three Landwehr brigades in Oberelsaß (Upper Alsace). On 19 September 1914, Armee-Gruppe-Gaede (An Armee-Gruppe was an improvised force larger than a corps and smaller than an army, subordinate to an army headquarters.) named after its commander General der Infanterie Hans Gaede (formerly the chief of staff of the XIV Corps) and renamed Armee-Abteilung Gaede (Army Detachment Gaede) on 30 January 1915.[7][a]

Battle

[edit]1914–1915

[edit]On 25 December, the French 66th Division and a battalion of Chasseurs Alpins attacked through deep snow and woods, to improve the French position on the peak of Hartmannswillerkopf. The French attack succeeded but the German defenders were pushed back only a short distance.[b] Division Fuchs of Armee-Abteilung Gaede attacked on a line from Hartmannswillerkopf to the Herrengluh ruins, Wolfskopf and Amselkopf in thick fog from 18 to 21 January 1915 and managed to surround the French positions, recapturing the summit of Hartmannswillerkopf and Hirzstein to the south, a French counter-attack being repulsed. The main German attack on 30 January, near Wattwiller, made early progress then bogged down against the French defences.[9] French attacks against Division Fuchs from 19 to 27 February were repulsed but on 26 February, a French attack gained 110 yards (100 m). On 5 March, the French captured a blockhouse and a German counter-attack by two regiments was defeated.[8]

The 152nd Infantry Regiment arrived to reinforce the Chasseurs Alpins; after a four-hour artillery preparation, the infantry and chasseurs captured two trench lines and took 250 prisoners but failed to penetrate new German trench lines close to the peak.[8] The French attacked again on 17 and from 23 March – 6 April; on 26 March, after a preparatory bombardment, the 152nd Regiment captured the summit of Hartmannswillerkopf in ten minutes, taking 400 prisoners and finding that the ground had been stripped of trees by the artillery exchanges.[8] The Germans suspended the offensive at Wattwiller and Steinbach to concentrate all reserves in the Hartmannswillerkopf area but on 17 March, the German army chief of staff, General Erich von Falkenhayn, ordered offensive operations in Alsace to cease.[10] The French success had enabled artillery-observers to direct their guns onto the Colmar–Mulhouse railway and local German attacks on 25 April took back the peak; the French recaptured it the next day the 152nd Regiment suffering 825 casualties.[11]

1915–1916

[edit]

In December 1915, Général Augustin Dubail commanding Groupe d'armées de l'Est (GAE: Eastern Army Group) planned a larger operation to consolidate the French position in the region by capturing Mulhouse. An attack on Hartmannswillerkopf by the 66e Division (General Marcel Serret), which had been fighting in the area all year was to be the prelude to the larger attack. The division was given another 250 guns for the attack, two of which were super-heavy 370 mm Filloux mortars, an average of one gun per 13 m (14 yd) of German front.[12] After several postponements, the French bombardment began on 21 December from Hartmannswillerkopf to Wattwiller. In the afternoon the 66e Division attacked, taking the peak and trenches at Hirtzstein to the north-west of Wattwiller as German reserves established a new front line on the eastern slopes.[13]

Next day, Landwehr Brigade 82 of the 12th Landwehr Division counter-attacked with reinforcements and re-took the peak, except for trenches on the north slope, which fell on 23 December.[13] The French 152e Régiment was almost annihilated, suffering 1,998 casualties from 21 to 22 December, along with Serret who was mortally wounded, the Germans taking 1,553 prisoners.[14] On the afternoon of 24 December, Landwehr Brigade 82 tried to re-gain the lost trenches at Hirtzstein, with the assistance of flame thrower teams but achieved only a partial success. During the evening of 28 December, French attacks captured several positions between Hartmannswillerkopf and Hirzstein, followed by German counter-attacks during the night; from 29 to 30 December and on 1 January 1916. The original front line was restored and on 8 January, Landwehr Brigade 187 re-captured the trenches at Hirzstein that had been lost on 21 December.[15]

Aftermath

[edit]Casualties

[edit]The fighting from 20 December 1915 to 8 January 1916 cost the French 7,465 casualties, about 50 per cent of the attacking force, of whom 1,103 were taken prisoner, along with thirty machine-guns. The Germans suffered 4,513 casualties, 1,700 men being taken prisoner.[16] Dubail stopped offensive operations to rest the survivors and to avoid French resources being drained away to little purpose; in Étude au sujet des opérations dans les Vosges (4 January 1916) Dubail recommended that such enterprises be avoided.[17]

Gallery

[edit]-

Sundgau, front line, 1914–1918

-

French attack, 22 March 1915

-

French attack, 26 March 1915

-

German attack, 25 April 1915

-

French attack, 21 December 1915

-

German counter-attack, 22 December 1915

-

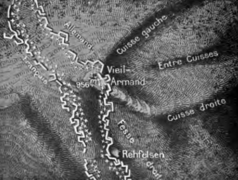

French and German positions at Vieil-Armand, 1916–1918

Notes

[edit]- ^ Armee-Gruppe (Army Group), a group within an army, under its command, usually an ad hoc measure. Armee-Abteilung (Army Detachment), was larger than a corps and detached from an army, under independent command; in practice the two terms were applied inconsistently. Heeresgruppe (Army Group) was the term for armies under one commander.[7]

- ^ A slightly different narrative, taken from Christian-Frogé (1922) has it that in early January, Hartmannswillerkopf was occupied by a platoon of the 1st Company, 28th Battalion, Chasseurs Alpins. At 7:00 a.m. on 4 January 1915, the party was counter-attacked and encircled by two German infantry companies. Despite many casualties, the chasseurs held on and the Germans were repulsed by a bayonet charge from another 28th Chasseurs Alpins platoon. On 9 January, two platoons on the summit were attacked by a battalion of German troops. The attackers were repulsed with many casualties and the French reinforced the peak to company strength. On 19 January, the 1st Company of the 28th Battalion occupied the top of Hartmannswillerkopf and the Germans attacked again after a bombardment. The 1st Company was encircled by about three German battalions and fought on through the night. Next day the 13th, 27th and 53rd batta;ions of the Chasseur Alpins arrived as reinforcements and prepared a hasty counter-attack to relieve the 28th Battalion. The German had already dug trenches and put out barbed wire and the French attack was a costly defeat. The French attacked again on 21 January because rifle-fire from the 1st Company and bugle calls could still be heard but were again repulsed with many casualties. The Germans bombarded the summit with Minenwerfer and blew up the French ammunition and supply dump, Second Lieutenant Canavy being buried and wounded. On 22 January, the firing and bugle-calls could no longer be heard, the 1st Company having surrendered after its three day and three night resistance, suffering 67 percent casualties, causing the Germans considerable surprise when they found only a handful of defenders.[8]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Humphries & Maker 2013, p. 95.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Strachan 2001, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b Michelin 1920, p. 37.

- ^ Tyng 2007, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Tyng 2007, p. 357.

- ^ a b Cron 2002, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Logier 2016.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 79, 170; Greenhalgh 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 75, 77.

- ^ a b Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 356.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, p. 77.

- ^ Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, p. 77; Humphries & Maker 2010, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, p. 416.

References

[edit]Books

- Cron, Hermann (2002) [1937]. Imperial German Army 1914–18: Organisation, Structure, Orders-of-Battle. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-70-3.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01880-8.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. II (1st ed.). Waterloo, Ont: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 9781554588268.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2013). Der Weltkrieg 1914: The Battle of the Frontiers and Pursuit to the Marne. Germany's Western Front: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. I. Part 1. Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-373-7.

- L'Alsace et les Combats des Vosges 1914–1918: Le Balcon d'Alsace, le Vieil-Armand, la Route des Crêtes [Alsace and the Vosges Battles 1914–1918: The Balcony of Alsace, Old-Armand and the Ridge Road]. Guides Illustrés Michelin des Champs de Bataille (1914–1918) (in French). Vol. IV. Clemont-Ferrand: Michelin & Cie. 1920. OCLC 769538059. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme, Yardley, PA ed.). New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 978-1-59416-042-4.

Websites

- Logier, D. (2016). "Les Grandes Battailes de la Grande Guerre: Les Vosges déc 1914 – mars 1915" [The Main Battles of the Great War: The Vosges December 1914 – March 1915]. www.chtimiste.com/. Notes from Christian-Frogé, 1922: La grande guerre 1914–1918: vécue, racontée, illustrée par les combattants [The Great War 1914–1918: Lived, Narrated, Illustrated by veterans]. France. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Christian-Frogé, René (1922). La grande guerre 1914–1918: vécue, racontée, illustrée par les combattants [The Great War 1914–1918: Lived, Narrated, Illustrated by veterans]. Paris: Quillet. OCLC 890214621.

- Foley, R. T. (2007) [2005]. German Strategy and the Path to Verdun: Erich von Falkenhayn and the Development of Attrition, 1870–1916. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 978-0-521-04436-3.

- Krause, J. (2013). Early Trench Tactics in the French Army: the Second Battle of Artois, May–June 1915 (1st ed.). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-5500-4.

- Sheldon, J. (2012). The German Army on the Western Front 1915. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-466-7.

- Koenig, E. F. (1933). Battle of Morhange–Sarrebourg, 20 August 1914 (PDF) (Report). CGSS Student Papers, 1930–1936. Fort Leavenworth, KS: The Command and General Staff School. OCLC 462117869. Retrieved 18 September 2016.[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]