Buddy Holly (song)

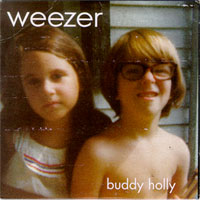

| "Buddy Holly" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Weezer | ||||

| from the album Weezer (The Blue Album) | ||||

| B-side | "Jamie" | |||

| Released | September 7, 1994 | |||

| Studio | Electric Lady (New York City) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:39 | |||

| Label | DGC | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Rivers Cuomo | |||

| Producer(s) | Ric Ocasek | |||

| Weezer singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Buddy Holly" on YouTube | ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

"Buddy Holly" is a song by the American rock band Weezer. The song was written by Rivers Cuomo and released by DGC as the second single from the band's debut album, Weezer (The Blue Album) (1994). The lyrics reference the song's namesake, 1950s rock-and-roll singer Buddy Holly, and actress Mary Tyler Moore. Released on September 7, 1994—which would have been Holly's 58th birthday—the song reached number two on the US Billboard Modern Rock Tracks chart and number 18 on the Billboard Hot 100 Airplay chart. Outside the US, the song peaked at number six in Canada, number 12 in the United Kingdom, number 13 in Iceland, and number 14 in Sweden. The song's music video, which features footage from Happy Days and was directed by Spike Jonze, earned considerable exposure when it was included as a bonus media file in Microsoft's initial successful release of the operating system Windows 95.

Rolling Stone ranked "Buddy Holly" number 484 in its list of "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time" (2021), raising it 15 spots from number 499 (2010), and raised from around 19 years prior, being ranked number 497 (2004).[6][7] The digital version of the single for "Buddy Holly" was certified gold by the RIAA in 2006.[8] VH1 ranked it as the 59th greatest song of the 1990s in December 2007.[9]

Background and writing

[edit]Songwriter Rivers Cuomo wrote "Buddy Holly" after his friends made fun of his Asian girlfriend.[10] He originally planned to exclude it from the album; he felt it was "cheesy" and perhaps did not represent the sound he was pursuing for Weezer. Producer Ric Ocasek persuaded him to include it. In the book River's Edge, Ocasek is quoted saying: "I remember at one point he was hesitant to do 'Buddy Holly' and I was like, 'Rivers, we can talk about it. Do it anyway, and if you don't like it when it's done, we won't use it. But I think you should try. You did write it and it is a great song.'" Bassist Matt Sharp recalled: "Ric said we'd be stupid to leave it off the album. We'd come into the studio in the morning and find little pieces of paper with doodles on them: WE WANT BUDDY HOLLY."[11]

Critical reception

[edit]Steve Baltin from Cash Box commented, "You’ve gotta love a song that makes reference to Mary Tyler Moore. Slightly poppier in its guitar sound than their first single, [...], this Ric Ocasek-produced song could help expand their already-growing fan base. Besides that, it mentions Mary, the woman who could turn the world on with her smile. Therefore, it has to be a hit."[12] John Robb from Melody Maker opined, "Weezer sound like The Proclaimers jamming with The Knack. This is pop-punk-by-numbers."[13] Pan-European magazine Music & Media wrote, "Made loud to play loud and sing along, it's the ideal power pop to cruise round this summer. That silly twin synth/guitar, betrays producer Ocasek, the one-time driver of New York's Cars."[14] A reviewer from Music Week gave the song four out of five, adding, "A short and sweet taster from the album which may not have the same quirky appeal of "Undone (The Sweater Song)", but has an attractive hook and a video to arouse interest."[15]

Johnny Cigarettes from NME commented, "A touching paean to nerdish social rejection from people who frankly deserve it. [...] But I am totally suckered by the pop majesty of a song that employs the long forgotten phrase Oo-ee-oo and drills an indelible mark on your taste buds such that you can never forget it's supernaturally banal chorus."[16] NME ranked it number five in their list of the Top 20 of 1995 in December 1995, writing, "Wahey! American rock ditches the pity-poor-me whingeing of grunge in favour of smiling faces, celestial Beach Boys-esque harmonies and The Tune That Ate Daytime Radio. Accompanied by the best video of the year."[17] Paul Evans from Rolling Stone noted "the self-deprecating humor" of lines like "I look like Buddy Holly/You're Mary Tyler Moore".[18]

Music video

[edit]

According to Matt Sharp, Spike Jonze came up with three ideas for the accompanying music video for "Buddy Holly". Sharp stated that two of the ideas "weren't great". When Jonze pitched the idea that came to be the song's video, Sharp told Jonze "I don't think you'll be able to pull it off", but the band agreed to do it.[19] The video was filmed at Charlie Chaplin Studios in Hollywood over a single day and portrays Weezer performing at Arnold's Drive-In from the 1970s television show Happy Days, combining footage of the band with clips from the show. Happy Days cast member Al Molinaro made a cameo; he introduces the band by describing them as, "Kenosha, Wisconsin's own Weezer", and before the band plays, Al asks the patrons to try the fish. In reality, it's Molinaro himself who was from Kenosha, while Weezer is from Los Angeles.[20]

In the climax, the video's stylist Casey Storm body doubled, and this allowed Fonzie to dance to the band's performance. The video also features brief cameos by some members of the band as dancers at Arnold's. Anson Williams, who played Potsie on Happy Days, objected to footage of him appearing in the video, but relented after receiving a letter from David Geffen, founder of Geffen Records.[11] According to drummer Pat Wilson, the video was achieved without computer graphics, only "clever" camerawork and editing. The video ended with Al complimenting the band on their performance, and asking if anyone had tried the fish, but they claimed it wasn't so good, and Al grudgingly agreed as he closed the restaurant for the night.[21] Sharp stated that the video was "pretty fucking wacky".[19]

The video was met with great popularity, and heavy rotation on MTV.[22] At the 1995 MTV Video Music Awards, it won Best Alternative Video, Breakthrough Video, Best Direction and Best Editing, and was nominated for Video of the Year.[23]

The "Buddy Holly" video was included on the Windows 95 installation CD-ROM, resulting in a skyrocket in popularity and earning Weezer a place in the history of MTV Music Video Awards.[24][25] Geffen did not tell Weezer they had negotiated with Microsoft to include the video; the band members, none of whom owned computers, were oblivious to the implications.[21] According to Wilson, "I was furious because at the time I was like, 'How are they allowed to do this without permission?' Turns out it was one of the greatest things that could have happened to us. Can you imagine that happening today? It's like, there's one video on YouTube, and it's your video."[21][26]

The video also appears in the music exhibit in the Museum of Modern Art. The music video was featured in Season 5, Episode 30 of MTV's Beavis and Butthead entitled "Here Comes the Bride's Butt" on June 9, 1995.

Track listings

[edit]

|

|

Personnel

[edit]- Rivers Cuomo – lead vocals, guitar, synthesizer

- Brian Bell – backing vocals

- Matt Sharp – bass guitar, backing vocals

- Patrick Wilson – drums

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[54] | Platinum | 30,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[55] | Platinum | 600,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[56] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]- ^ Brod, Doug (June 2008). "The "Buddy Holly" Story". Spin. 24 (6): 16. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ Braun, Laura (September 23, 2016). "How Weezer's 'Pinkerton' Went From Embarrassing to Essential". Rollingstone. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "Weezer / Pixies". Delawareonline. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Various Artists - Whatever: The '90s Pop and Culture Box (2005) Review at AllMusic. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "Weezer brings the fun, and the Pixies, to tour". The News & Observer. July 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved November 24, 2007.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 15, 2021. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "RIAA searchable database". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ 100 Greatest Songs of the '90s Archived February 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Weezer Songs". Rolling Stone. June 18, 2018. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Buddy Holly: How Four LA Rockers Created the Definitive Hipster-Doofus Battle Cry", Ryan Domball, Blender, November 2008

- ^ Baltin, Steve (October 29, 1994). "Pop Singles — Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Robb, John (April 29, 1995). "Singles". Melody Maker. p. 34. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "New Releases: Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 12, no. 25. June 24, 1995. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Reviews: Singles" (PDF). Music Week. April 15, 1995. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Cigarettes, Johnny (April 29, 1995). "Singles". NME. p. 34. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "'Tonic Boom! The On Top 20". NME. December 23, 1995. p. 35. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Paul (December 29, 1994-January 12, 1995). "The year in recordings". Rolling Stone. Issue 698/699.

- ^ a b Hatsios, Natasha (December 2, 1994). "just like Buddy Holly... Well, Richie Cunningham anyway". Imprint. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ Potente, Joe (October 30, 2015). "Al Molinaro, actor from Kenosha, dead at 96". Kenosha News. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ a b c Valania, Jonathan (October 2, 2014). "UNDONE: The Complete Oral History of Weezer". Magnet. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ Luerssen, John D. Rivers' Edge: The Weezer Story. ECW Press, 2004, ISBN 1-55022-619-3 p. 132

- ^ "1995 MTV Video Music Awards". Rock on the Net. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ "1995 MTV Video Music Awards on mtv.com". mtv.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ "That time when Weezer was on a Windows installation disc - Alan Cross". June 29, 2018. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ "Knowledge Drop: Weezer Had No Idea The Music Video For "Buddy Holly" Would Be Included With Windows 95". Archived from the original on July 29, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ Buddy Holly (UK 7-inch single vinyl disc). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GFS 88.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (UK cassette single sleeve). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GFSC 88.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (UK CD single liner notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GFSTD 88.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (Dutch CD single liner notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GED 22052.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (European maxi-CD single liner notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GED 21978.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (Australian CD single disc notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GEFDS 21968.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Buddy Holly (Australian cassette single cassette notes). Weezer. Geffen Records. 1995. GEFCS 19302.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "The ARIA Australian Top 100 Singles Chart – Week Ending 16 Apr 1995". Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016 – via imgur.com.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (PDF ed.). Mt Martha, Victoria, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 298.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 7984." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 8014." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 12, no. 19. May 13, 1995. p. 23. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Íslenski Listinn Topp 40 (25.6. '95 – 1.7. '95)". Dagblaðið Vísir (in Icelandic). June 24, 1995. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – Buddy Holly". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – week 29, 1995" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer – Buddy Holly" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer – Buddy Holly". Singles Top 100. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer Chart History (Radio Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer Chart History (Alternative Airplay)". Billboard. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer Chart History (Mainstream Rock)". Billboard. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "Weezer Chart History (Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Hit Tracks of 1995". RPM. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2019 – via Library and Archives Canada.

- ^ "Årslista Singlar, 1995" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ "The Year in Music: Hot 100 Singles Airplay" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 107, no. 51. December 23, 1995. p. YE-32. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ "The Year in Music: Hot Modern Rock Tracks". Billboard. Vol. 107, no. 51. December 23, 1995. p. YE-77.

- ^ "New Zealand single certifications – Weezer – Buddy Holly". Radioscope. Retrieved December 19, 2024. Type Buddy Holly in the "Search:" field.

- ^ "British single certifications – Weezer – Buddy Holly". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved April 5, 2024.

- ^ "American single certifications – Weezer – Buddy Holly". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved October 25, 2024.