Cinema of Naples

Naples played a prominent role in the rise of another industry of movement: the motion picture industry.

The history of cinema in Naples begins at the end of the 19th century and over time it has recorded cinematographic works, production houses and notable filmmakers. Over the decades, the Neapolitan capital has also been used as a film set for many works, over 600 according to the Internet Movie Database, the first of which would be Panorama of Naples Harbor from 1901.

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

During his stay in Naples in 1888, the French inventor Étienne-Jules Marey, with his chronophotograph, imprinted a short film of the Faraglioni entitled Vague, baie de Naples.[4] The cinema arrived in Naples three months after its invention by the Lumiere Brothers, (although in the Neapolitan capital Menotti Cattaneo had patented a similar machine[5]): on 30 March 1896, at the Salone Margherita there was the first screening of the works of the French brothers.[4] In 1896 the Lumiere Company shot some films in the Neapolitan province, including in the capital, Levée de filets de peche, Via Marina and Santa Lucia,[4] effectively making it one of the cities with the oldest cinematographic testimony.

In May 1898 the Paduan Mario Recanati, considered the first in Italy to distribute and trade films, opened the first cinema in Galleria Umberto I at number 90;[5] in that year, the new invention was also used for advertising purposes, achieving such success as to worry the Naples Police Headquarters.[4]

20th century

[edit]From the start of the century to the First World War

[edit]In the early years of the twentieth century, the first Italian film house, namely the Titanus (originally Monopolio Lombardo),[6] was built in the city, in the Vomero district. Founded by Gustavo Lombardo in 1904, it is the largest and probably the most famous film house in the country.[7]

The first short film is due to Roberto Troncone who shot Il ritorno delle carrozze da Montevergine in 1900; he filmed the eruption of Vesuvius with great popular success and in 1907 projected Il delitto delle Fontanelle in the Sala Elgè in via Poerio, considered the first film produced in Naples.[8]

In 1906 the city newspapers, faced with the success of cinema, witnessed by the twenty-seven cinemas, spoke of an "epidemic":[4] the inauguration of the International Cinema caused riots, put down by the police and it was thought to widen Piazza Carità to solve the problems of circulation caused by the presence of this room.[4] In 1908, six of the seven film magazines published in Italy were Neapolitan and Gustavo Lombardo's «Lux» magazine was also widespread abroad.[4][9]

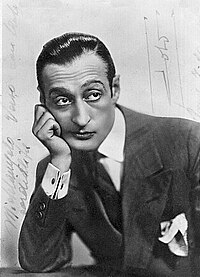

In 1907, with La dea del mare by Salvatore Di Giacomo,[10] Francesca Bertini made her cinema debut,[11] defined by Melania G. Mazzucco as «the undisputed queen of Italian silent cinema»:[12] Tuscan by birth but with a Neapolitan father she moved to the Neapolitan capital as a child learning its language:[10] she is considered the first diva of cinema and at the time her fame was such that the correspondence came to her specifying only the city where she lived;[13] she was also a screenwriter under the pseudonym Frank Bert.[12]

Around 1913, Giuseppe Di Luggo's Polifilms company was officially founded.[14] Unlike the others, defined mostly small in size, set up and managed with familiar criteria» and it constituted a «qualitative leap».[15] Being in financial difficulties, the manufacturer, based in via Cimarosa,[16] sold its systems and studios to Gustavo Lombardo in 1919: these, in addition to working in the sector's publishing, distributed abroad of films and the foundation of Titanus, brought to Italy the first films of Charlie Chaplin in 1915 and Intolerance by D. W. Griffith in 1916.[17] Gian Piero Brunetta defines it as an exception wherever «the economic history of Italian cinema lacks the origins of the figures of tycoons comparable to the Hollywood ones of Mayer, Fox, Goldwyn, or the Warner Brothers».[18]

Film Dora was born around 1909, subsequently becoming Dora Film, with Elvira Notari at work as director, screenwriter and producer, of whose work the Library of Congress conserves some copies of A Piedigrotta,[19][20] opening in 1925 in New York City the Dora Film of America, for the public made up of emigrants[21] who will be able to see them with the titles of Mary the Crazy Woman, Blood and Duty, The Orphan of Naples and From Piave to Trieste.[18] Brunetta also defined his films «events inspired by successful songs, or taken from drama, stories of street urchins and "piccerille" (children) who get lost».[18] Family-run production house, after starting to color the films, it went on to produce, with Elvira Notari at the helm, films based on plays by Federico Stella and Crescenzo Di Maio, aiming, according to the memory of her son Eduardo, to make «'o cinema de' napulitane» (the cinema of the Neapolitans).[20]

The period between the two wars

[edit]Even in the Fascist era, very little inclined to dialectal folklore, "local" films were born, some of real importance.

— Martini, pag. 218

In the two-year period 1924–1925 a third of Italian films were shot in the Neapolitan capital, in a shed located on the corner of via Cimarosa and via Aniello Falcone.[16] In 1934 Eduardo and Peppino De Filippo made their debut as film actors in Il cappello a tre punte while Naples of other times, from 1938, saw Vittorio De Sica as an actor; in 1937, with Fermo con le mani! by Gero Zambuto, Neapolitan legend Totò made his debut as a film actor.[22]

In the 1930s, however, film production moved to Rome, according to Goffredo Lombardo because his father Gustavo wanted to «change the production system and the quality of films»;[9] however, according to the historian Daniela Manetti because a provision of the censorship office for cinema in 1928 already constituted «A very serious limitation to the Neapolitan genre that Lombardo has made appreciated even outside the regional borders and a serious mortgage for Naples as a city of cinema».[9]

From the postwar period to the end of the century

[edit]

The early post-war years in Naples were brought to the cinema by Roberto Rossellini who set the second episode of the Oscar-nominated film Paisan in Naples.[23] The Four Days of Naples, by Nanni Loy, from 1962, was also nominated for an Oscar;[24] while the Neapolitan Francesco Rosi filmed Le mani sulla città in 1963: the film, awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival of the same year,[25] is defined as a «merciless portrait of a Naples bewildered and devastated by savage and suffocating building speculation that started in the 1950s».[26]

Two films taken from scripts and directed by Raffaello Matarazzo, Catene in 1949 and I figli di nessuno in 1951, became «cinematographic triumphs»:[27] the first was included among the 100 Italian films to be saved,[28][29] exceeding one billion liras at the time.[30]

In 1981 Neapolitan legend Massimo Troisi made his debut as an actor and director in I'm Starting from Three: the film collected 14 billion liras against an expense of 450 million, remaining on the bill in a Roman cinema for six hundred days,[31] winning among other things two David di Donatello Awards, for best film and best leading actor.[32]

21st century

[edit]In the 21st century, the importance of Naples as a center of film production, filming location and film subject is established, with the release of internationally successful films such as L'uomo in più by Paolo Sorrentino or series such as Gomorra, L'amica geniale and The Bastards of Pizzofalcone.[33][34]

Neapolitan actors and directors awarded internationally

[edit]

Among the Neapolitan actors, Sophia Loren won the Oscar in 1960 for La Ciociara and the Oscar for her career in 1991, as well as the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, seven years later,[35] while Totò is defined by Treccani as a «comedian of great strength and exceptional mime».[36] Massimo Troisi, also a director whose film Il postino received two Oscar nominations, is defined by Treccani as an «Actor with engaging comedy based above all on virtuosic monologues».[37] Tina Pica was also an important supporting actress for Naples' cinema history, winning the Nastro d'Argento for Best Supporting Actress in 1955.[38]

Among the directors, Vittorio De Sica, who identified himself as a Neapolitan,[39] was awarded four times with an Oscar.[40]

Naples has also been widely represented in national and international cinematography: great directors have followed one another over the years, starting with the Lumiere Brothers who in 1898 made some of their first shots on the Naples waterfront with their silent documentary short film Naples, passing through the sixties and seventies with the films of Mario Monicelli,[41] Roberto Rossellini with Paisà, Pier Paolo Pasolini,[42] Ettore Scola,[43] Nanni Loy,[24] Dino Risi with Operazione San Gennaro and many others, up to the present day with Giuseppe Tornatore,[44] Gabriele Salvatores,[45] Matteo Garrone,[46] John Turturro[47] and Ferzan Özpetek with Napoli velata.

Films set in Naples awarded internationally

[edit]The films set in Naples are cinematographic films produced in the Neapolitan city which include fictions, soap operas, music videos, documentaries, short films, animated films, television programmes, commercials and chronophotographs.

Among the most important films set in Naples are: Paisà (winner of the Nastro d'Argento),[48] L'Oro di Napoli (winner of two Nastri d'Argento in 1955),[49] Ricomincio da tre,[32] Matrimonio all'Italiana (David di Donatello for Best Actor to Marcello Mastroianni, Best Actress to Sophia Loren, Best Producer to Carlo Ponti and Best Director to Vittorio De Sica in 1965),[50] Ieri, oggi e domani (winner of the Oscar for the best foreign film)[51] and Carosello napoletano, winner of the Prix International 1954 at the Cannes Film Festival.[52]

History

[edit]The ancient centre, the coast and the hinterland of Naples are the oldest cinematographic evidence of Italian cinema. In fact, the Lumière Brothers carried out some filming in 1898 on the Riviera di Chiaia, in Via Toledo, on the Vesuvius funicular and in other areas of the city, some filming in 1898. In the Galleria Umberto I the Recanati room was already active since 1897, the first cinema in Italy created by the Venetian Mario Recanati.[53]

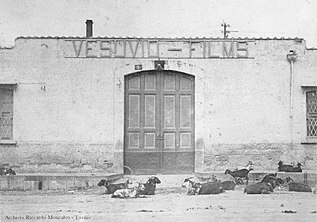

From this experience, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the city became one of the poles of the nascent Italian film industry, together with Rome and Turin: some of the first Italian film production houses arose in the Vomero district, such as Partenope Film of the Troncone Brothers in 1906 in via Francesco Solimena and Giuseppe Di Luggo's Polifilms in 1915 in via Domenico Cimarosa, which was taken over and absorbed in 1918 by Gustavo Lombaroo's Lombardo Film, which would later become Titanus in 1928.[54] Famous was the activity of Elvira Notari with her Dora Film (located in Via Roma, 91) and of many other directors, producers, actors and workers, who later moved most of them to the capital, when the Fascist Regime decided to centralize film production in Cinecittà. In Naples, Notari also founded a Film Art School (in Via Leonardo di Capua, 15).[55][56][57] In via Purgatorio, in the Poggioreale area, Vesuvio Films was founded by Augusto Turchi in 1909, one of the first film manufacturers in Italy which produced over fifty films until 1914.[58]

As is already the case in other European and American cities, due to the so constant and widespread presence of cinematographic reality in the city of Naples and its surroundings, the so-called cinematographic tourism has also developed here, which offers the possibility of visiting the places immortalized by the most great film directors (such as De Sica or Rossellini) in their films, organizing real itineraries and guided visits to the locations of the most famous films.[59]

The pioneering times of the Neapolitan film industry ended during the Fascist period: the emphasis placed on the development of Rome and the lowering of costs due to centralization meant that the production of Italian films was transferred to the banks of the Tiber, where they were built the Cinecittà establishments.[60]

Actuality

[edit]In the last ten years, thanks to the great work carried out by the Campania Region Film Commission, Naples has become one of the most loved sets in the world. Over 400 productions have decided to shoot films and TV series in Naples between 2015 and 2024.

References

[edit]- ^ David Clarke, The Cinematic City, Routledge, pag. 49 on Google Books.

- ^ CyberItalian. "Totò, un grande attore – parte 2 (Totò a great actor – part 2) – Cyber Italian Blog" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Michele, De Lucia (27 November 2021). "Antonio De Curtis aka Totò". CAMPANIA WELCOME. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barbagallo, pages 139–144

- ^ a b Picone, Generoso (1 December 2014). I napoletani (in Italian). Gius.Laterza & Figli Spa. ISBN 978-88-581-1861-0.

- ^ "Titanus, lo scudo nobile del cinema italiano". La Repubblica (in Italian). 16 February 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "La storia di Titanus". Titanus (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Napoli nel Cinema". Napoli nel Cinema (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b c VV, AA; Ferrandino, Vittoria; Napolitano, Maria Rosaria (22 July 2015). Storia d'impresa e imprese storiche. Una visione diacronica: Una visione diacronica (in Italian). FrancoAngeli. ISBN 978-88-917-1173-1.

- ^ a b Palumbo, Agnese (2015). 101 DONNE CHE HANNO FATTO GRANDE NAPOLI (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. ISBN 978-88-541-8261-5. OCLC 1136964212.

- ^ "Francesca Bertini". IMDb. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b "BERTINI, Francesca in "Enciclopedia del Cinema"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Lodi, Giovanni (2015). "Forse non tutti sanno che…". Dental Cadmos (in Italian). 83 (9): 583. doi:10.1016/s0011-8524(15)30088-x. hdl:2434/351331. ISSN 0011-8524.

- ^ VV, AA; Ferrandino, Vittoria (27 August 2015). Storia d'impresa e imprese storiche. Una visione diacronica: Una visione diacronica (in Italian). Franco Angeli Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-917-3071-8.

- ^ De Agostini. "Il cinema Grande storia illustrata volume nove". Istituto Geografico de Agostini (in Italian). Novara: 46.

- ^ a b "La storia della prima Cinecittà italiana al Vomero". Vomero Magazine (in Italian). 4 April 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "LOMBARDO, Gustavo in "Dizionario Biografico"". Treccani (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b c Brunetta, vol. 1, pag. 32

- ^ Notari, Elvira. "Quando il cinema era donna". briganti.info (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b Bruno, Giuliana (1993). Streetwalking on a Ruined Map: Cultural Theory and the City Films of Elvira Notari. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02533-9.

- ^ "NOTARI, Elvira in "Enciclopedia del Cinema"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Martini, pag. 218

- ^ "1950 | Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences". www.oscars.org. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b Oliveri, Ugo Maria; Rovinello, Mario; Speranza, Paolo. L'onda della libertà Le Quattro Giornate di Napoli tra storia, letteratura e cinema. Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane. p. 1.

- ^ "Le mani sulla città in "Enciclopedia del Cinema"". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Fusco, Gaetano. Le mani sullo schermo: il cinema secondo Achille Lauro. Liguori Editore. p. 73.

- ^ Morreale, Emiliano (2011). Così piangevano: il cinema melò nell'Italia degli anni Cinquanta (in Italian). Donzelli Editore. p. 107. ISBN 978-88-6036-582-8.

- ^ "Cento film e un'Italia da non dimenticare". Movieplayer.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Poppi, Roberto (2002). I registi: dal 1930 ai giorni nostri (in Italian). Gremese Editore. p. 279. ISBN 978-88-8440-171-7.

- ^ Cocciardo, Eduardo (2005). L'applauso interrotto : poesia e periferia nell'opera di Massimo Troisi (in Italian) (1st ed.). Pollena Trocchia, Naples: NonSoloParole. p. 68. ISBN 88-88850-31-7. OCLC 61441685.

- ^ a b "La Stampa – Consultazione Archivio". www.archiviolastampa.it. p. 19. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Napoli, il cinema resiste: ecco i set ancora aperti". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Archivi Mario Franco – IL CINEMA A NAPOLI DALLE ORIGINI AD OGGI". Fondazione Morra (in Italian). Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Lòren, Sophia nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Totò nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Troisi, Massimo nell'Enciclopedia Treccani". www.treccani.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "1955: Nastro d'argento a Tina Pica, regina del cinema –". Rai Teche (in Italian). 30 March 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Foto e lettere inedite di De Sica, il ciociaro cosmopolita che voleva essere napoletano". Corriere del Mezzogiorno (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "VITTORIO DE SICA, UN ITALIANO CON 4 OSCAR". VeniVidiVici (in Italian). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Mario Monicelli e Rap – 100 anni di cinema". www.comune.napoli.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Pasolini e Napoli 'Caro Eduardo giriamo un film' – la Repubblica.it". Archivio – la Repubblica.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ IDN, Redazione (24 June 2015). "Maccheroni di Ettore Scola – Itinerari di Napoli" (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Tornatore: 'Senza Napoli non avrei mai fatto il regista'". Repubblica TV – Repubblica (in Italian). 9 February 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Gabriele Salvatores: "Il mio ragazzo invisibile è nato in una scuola di Secondigliano"". la Repubblica (in Italian). 3 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Napoli, il primo ciak del nuovo film di Matteo Garrone". Informareonline (in Italian). 25 September 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Esposito, Roberta (1 June 2014). "Video. La passione napoletana firmata John Turturro". Vesuvio Live (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Paisà". cinematografo.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Premi del cinema 1955". Wayback Machine (in Italian). 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Matrimonio all'italiana". cinematografo.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "1965 | Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences". www.oscars.org. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "CAROSELLO NAPOLETANO – Festival de Cannes". www.festival-cannes.com (in French). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Vetrano, Dresiana. "Napoli ex Capitale anche del Cinema. Così il fascismo distrusse la Cinecittà napoletana". Identità Insorgenti (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "La prima casa cinematografica d'Italia è nata a Napoli!". Grandenapoli.it. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "cinema napoletano elvira notari" (in Italian). June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Napoli nel Cinema". Napoli nel Cinema (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ "Elvira Notari". enciclopedia delle donne (in Italian). Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Un'altra Italia = Pour une histoire du cinéma italien | WorldCat.org (in English, Italian, and French). Cinémathèque française. 1998. ISBN 2900596254. OCLC 43439536. Retrieved 8 December 2022 – via www.worldcat.org.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Campania Movietour | In viaggio nei luoghi del cinema – A Cinematic Journey on Movie Locations". 12 September 2018. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Paliotti, Vittorio; Grano, Enzo (1969). Napoli nel cinema (in Italian). Azienda autonoma soggiorno cura e turismo. p. 167.

Bibliography

[edit]- Francesco Barbagallo, Napoli, Belle Époque, Editori Laterza. ISBN 978-88-581-2105-4

- Gian Piero Brunetta, Cent'anni di cinema italiano, Economica Laterza. ISBN 88-365-3442-2

- Giulio Martini, I luoghi del cinema, Touring Club Italiano, ISBN 88-365-3442-2

- Vittoria Ferrandino and Maria Rosaria Napolitano, FrancoAngeli, Storia d’impresa e imprese storiche. Una visione diacronica

- Emiliano Morreale, Così piangevano: il cinema melò nell'Italia degli anni Cinquanta, Donzelli Editore