Continental shelf pump

| Part of a series on the |

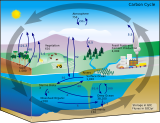

| Carbon cycle |

|---|

|

In oceanic biogeochemistry, the continental shelf pump is proposed to operate in the shallow waters of the continental shelves, acting as a mechanism to transport carbon (as either dissolved or particulate material) from surface waters to the interior of the adjacent deep ocean.[1]

Overview

[edit]Originally formulated by Tsunogai et al. (1999),[1] the pump is believed to occur where the solubility and biological pumps interact with a local hydrography that feeds dense water from the shelf floor into sub-surface (at least subthermocline) waters in the neighbouring deep ocean. Tsunogai et al.'s (1999)[1] original work focused on the East China Sea, and the observation that, averaged over the year, its surface waters represented a sink for carbon dioxide. This observation was combined with others of the distribution of dissolved carbonate and alkalinity and explained as follows :

- the shallowness of the continental shelf restricts convection of cooling water

- as a consequence, cooling is greater for continental shelf waters than for neighbouring open ocean waters

- this leads to the production of relatively cool and dense water on the shelf

- the cooler waters promote the solubility pump and lead to an increased storage of dissolved inorganic carbon

- this extra carbon storage is augmented by the increased biological production characteristic of shelves[2]

- the dense, carbon-rich shelf waters sink to the shelf floor and enter the sub-surface layer of the open ocean via isopycnal mixing

Significance

[edit]Based on their measurements of the CO2 flux over the East China Sea (35 g C m−2 y−1), Tsunogai et al. (1999)[1] estimated that the continental shelf pump could be responsible for an air-to-sea flux of approximately 1 Gt C y−1 over the world's shelf areas. Given that observational[3] and modelling[4] of anthropogenic emissions of CO2 estimates suggest that the ocean is currently responsible for the uptake of approximately 2 Gt C y−1, and that these estimates are poor for the shelf regions, the continental shelf pump may play an important role in the ocean's carbon cycle.

One caveat to this calculation is that the original work was concerned with the hydrography of the East China Sea, where cooling plays the dominant role in the formation of dense shelf water, and that this mechanism may not apply in other regions. However, it has been suggested[5] that other processes may drive the pump under different climatic conditions. For instance, in polar regions, the formation of sea-ice results in the extrusion of salt that may increase seawater density. Similarly, in tropical regions, evaporation may increase local salinity and seawater density.

The strong sink of CO2 at temperate latitudes reported by Tsunogai et al. (1999)[1] was later confirmed in the Gulf of Biscay,[6] the Middle Atlantic Bight[7] and the North Sea.[8] On the other hand, in the sub-tropical South Atlantic Bight reported a source of CO2 to the atmosphere.[9]

Recently, work[10][11] has compiled and scaled available data on CO2 fluxes in coastal environments, and shown that globally marginal seas act as a significant CO2 sink (-1.6 mol C m−2 y−1; -0.45 Gt C y−1) in agreement with previous estimates. However, the global sink of CO2 in marginal seas could be almost fully compensated by the emission of CO2 (+11.1 mol C m−2 y−1; +0.40 Gt C y−1) from the ensemble of near-shore coastal ecosystems, mostly related to the emission of CO2 from estuaries (0.34 Gt C y−1).

An interesting application of this work has been examining the impact of sea level rise over the last de-glacial transition on the global carbon cycle.[12] During the last glacial maximum sea level was some 120 m (390 ft) lower than today. As sea level rose the surface area of the shelf seas grew and in consequence the strength of the shelf sea pump should increase.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Tsunogai, S.; Watanabe, S.; Sato, T. (1999). "Is there a "continental shelf pump" for the absorption of atmospheric CO2". Tellus B. 51 (3): 701–712. Bibcode:1999TellB..51..701T. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0889.1999.t01-2-00010.x.

- ^ Wollast, R. (1998). Evaluation and comparison of the global carbon cycle in the coastal zone and in the open ocean, p. 213-252. In K. H. Brink and A. R. Robinson (eds.), The Global Coastal Ocean. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Takahashi, T.; Sutherland, S. C.; Sweeney, C.; et al. (2002). "Global sea-air CO2 flux based on climatological surface ocean pCO2, and seasonal biological and temperature effects". Deep-Sea Research Part II. 49 (9–10): 1601–1622. Bibcode:2002DSR....49.1601T. doi:10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00003-6.[dead link]

- ^ Orr, J. C.; Maier-Reimer, E.; Mikolajewicz, U.; Monfray, P.; Sarmiento, J. L.; Toggweiler, J. R.; Taylor, N. K.; Palmer, J.; Gruber, N.; Sabine, Christopher L.; Le Quéré, Corinne; Key, Robert M.; Boutin, Jacqueline; et al. (2001). "Estimates of anthropogenic carbon uptake from four three-dimensional global ocean models" (PDF). Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 15 (1): 43–60. Bibcode:2001GBioC..15...43O. doi:10.1029/2000GB001273. hdl:21.11116/0000-0004-ECB6-5. S2CID 129094847.

- ^ Yool, A.; Fasham, M. J. R. (2001). "An examination of the "continental shelf pump" in an open ocean general circulation model". Global Biogeochem. Cycles. 15 (4): 831–844. Bibcode:2001GBioC..15..831Y. doi:10.1029/2000GB001359.

- ^ Frankignoulle, M.; Borges, A. V. (2001). "European continental shelf as a significant sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 15 (3): 569–576. Bibcode:2001GBioC..15..569F. doi:10.1029/2000GB001307.

- ^ DeGrandpre, M. D.; Olbu, G. J.; Beatty, C. M.; Hammar, T. R. (2002). "Air-sea CO2 fluxes on the US Middle Atlantic Bight". Deep-Sea Research Part II. 49 (20): 4355–4367. Bibcode:2002DSR....49.4355D. doi:10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00122-4.

- ^ Thomas, H.; Bozec, Y.; Elkalay, K.; Baar, H. J. W. De (2004). "Enhanced open ocean storage of CO2 from shelf sea pumping" (PDF). Science. 304 (5673): 1005–1008. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1005T. doi:10.1126/science.1095491. hdl:11370/e821600e-4560-49e8-aeec-18eeb17549e3. PMID 15143279. S2CID 129790522.

- ^ Cai, Wei-Jun; Wang, Zhaohui Aleck; Wang, Yongchen (2003). "The role of marsh-dominated heterotrophic continental margins in transport of CO2 between the atmosphere, the land-sea interface and the ocean". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (16): 1849. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.1849C. doi:10.1029/2003GL017633.

- ^ Borges, A. V. (2005). "Do we have enough pieces of the jigsaw to integrate CO2 fluxes in the Coastal Ocean?". Estuaries. 28: 3–27. doi:10.1007/BF02732750.

- ^ Borges, A. V.; Delille, B.; Frankignoulle, M. (2005). "Budgeting sinks and sources of CO2 in the coastal ocean: Diversity of ecosystems counts". Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (14): L14601. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3214601B. doi:10.1029/2005GL023053. hdl:2268/2118. S2CID 45272714.

- ^ Rippeth, T. P.; Scourse, J. D.; Uehara, K.; McKeown, S. (2008). "Impact of sea-level rise over the last deglacial transition on the strength of the continental shelf CO2 pump". Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (24): L24604. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3524604R. doi:10.1029/2008GL035880. S2CID 1049049.