Doug Sahm

Doug Sahm | |

|---|---|

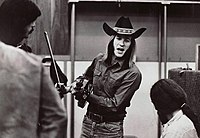

Sahm in 1974 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Douglas Wayne Sahm |

| Also known as | Little Doug Doug Saldaña Samm Dogg Wayne Douglas |

| Born | November 6, 1941 San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | November 18, 1999 (aged 58) Taos, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Genres | Tejano/Tex-Mex, Country, Rock, Blues, Rhythm and blues |

| Occupation(s) | Musician singer-songwriter bandleader |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar, steel guitar, fiddle, mandolin, bajo sexto, dobro, drums, piano |

| Years active | 1946–1999 |

| Labels | (Various)

|

Douglas Wayne Sahm (November 6, 1941 – November 18, 1999) was an American musician, singer-songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist from San Antonio, Texas. He is regarded as a key Tex-Mex music and Texan Music performer. San Antonio's conjunto and blues and later the hippie scene of San Francisco[1] helped create his blend of music, with which he found success performing in 1970s Austin, Texas.

He made his recording debut as "Little Doug" in 1955. In 1965, Huey P. Meaux produced Sahm and the Sir Douglas Quintet's "She's About a Mover." Atlantic Records signed Sahm and released his debut solo album Doug Sahm and Band in 1973. In 1989, Sahm formed the supergroup the Texas Tornados with fellow Tex-Mex musicians Augie Meyers, Freddy Fender and Flaco Jiménez. The Texas Tornados toured successfully, and one of their releases earned a Grammy Award. In 1999, Sahm died during a vacation trip.

Early life and start in music

[edit]Doug Sahm was born in San Antonio, Texas, on November 6, 1941, to Victor A. Sahm, Sr. and Viva Lee (née Goodman).[2] The Sahm family had migrated to the United States from Germany early in the 20th century, and settled initially in Galveston, Texas. Sahm's grandparents, Alfred and Alga, owned a farm near Cibolo, Texas. Alfred Sahm was a musician who played with the polka band The Sahm Boys. During the Great Depression, Sahm's parents moved to San Antonio, where Victor worked at Kelly Field Air Force base.[3]

Sahm began singing at age five, and took up the steel guitar at age six. The same year, he appeared on San Antonio's radio station KMAC and performed the Sons of the Pioneers' "Teardrops in My Heart".[4] He was regarded as a child prodigy on the steel guitar.[5][6][7] His mother took him to a local music school, but his teacher turned him down soon after. His teacher explained he could not teach Sahm to read music, and the boy could already play by ear. Sahm often appeared at a local club, The Barn, which his uncle co-owned with Charlie Walker.[8] By the time he was eight, he could play the fiddle and mandolin, and he began to appear on the Louisiana Hayride as "Little Doug".[2] He also performed shows with Hank Williams, Faron Young and Hank Thompson. At age thirteen, he was offered a spot on the Grand Ole Opry that his mother declined, wanting him to finish school.[2] In 1953, Sahm met Augie Meyers while he purchased baseball cards at Meyer's mother's grocery store,[9] and the two became friends. Meyers and Sahm discussed forming a band, but nothing came of it as both played with different groups. Meyers mastered the accordion, piano and rhythm guitar.[10] Sahm grew up on the East side of San Antonio, a predominantly black neighborhood. He listened from his home to the live performances of T-Bone Walker and other blues artists who appeared at a nearby blues bar, the Eastwood Country Club.[8] Sahm's neighbor, Homer Callahan, introduced him to the records of Howlin' Wolf, Lonesome Sundown, Fats Domino, Jimmy Reed, and Atlantic and Excello Records.[11]

In 1955, producer Charlie Fitch released Sahm's debut single on Sarg Records.[12] Cataloged with the number 113-45 on the label's releases, the pairing of "A Real American Joe" with "Rollin' Rollin'" was credited to Little Doug.[13] The same year, Sahm formed his first band, The Kings. A year later, one of his concerts in school was interrupted by the principal after Sahm started imitating Elvis Presley's gyrations. The students left the auditorium and headed to Sahm's house to continue listening to the band.[8] As he continued performing country music, fiddler J. R. Chatwell, who played with bandleader Adolph Hofner, mentored him. The music of Lefty Frizzell, Howlin' Wolf, Lonesome Sundown, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, T-Bone Walker, Floyd Tillman, and San Antonio musicians Johnny Owen and Ricky Aguirre influenced him during his teenage years.[14][15][8]

Sahm enjoyed success performing in San Antonio nightclubs,[16] as he played a blend of music that consisted of rhythm and blues with the addition of the West Side tenor saxophone player Eracleo "Rocky" Morales.[17] The "West Side Sound", characteristic of San Antonio, consisted of a blend of genres: country music, conjunto, rhythm and blues, polka and rock and roll.[18][19][20] Meanwhile, Sahm performed on guitar six nights a week with Jimmy Johnson's band.[8] Saxophonist Spot Barnett invited him to play at the Ebony rhythm and blues club.[9]

Sahm fronted three bands: The Pharaohs, The Dell-Kings and The Markays. He released the song "Crazy Daisy" (1959), and he had a local hit with "Why Why Why" (1960) on Renner Records.[21][22] Sahm graduated from high school the same year. He had another local hit with "Crazy, Crazy Feeling" (1961);[8] "Just A Moment" (1961) and "Lucky Me" (1963) followed.[23] By 1964, Sahm was dropped by the Renner label and he tried to convince Huey P. Meaux to sign him. Meaux, the owner of SugarHill Recording Studios, was enjoying success with Dale and Grace and Barbara Lynn, and turned Sahm down.[7]

The Sir Douglas Quintet

[edit]

Meaux produced songs that appeared on the music charts in the 1960s, but because of Beatlemania and the British Invasion, his records stopped selling well. Determined to find the reason for the commercial success of The Beatles sound, Meaux said he purchased several of their records and rented three rooms at the Wayfarer Hotel in San Antonio. According to his account, he drank a case of Thunderbird wine in the process.[24] Meaux felt the Beatles' songs shared a common ground with traditional two-step Cajun music.[25] He called Sahm and asked him to write songs based on that style, and to let his hair grow.[24] Sahm and Meyers appeared with The Dave Clark Five in San Antonio, where they were featured on the program, with their respective bands, as the opening acts. Sahm appeared with the Markays, and Meyers the Goldens.[26] Meyers attributed Meaux's interest in recording Sahm and himself to their performance at the concert.[27]

Sahm put together a band with Meyers (keyboard), Frank Morin (saxophone), Harvey Kagan (bass) and Johnny Perez (drums).[23] Based on The Beatles' "She's a Woman", Sahm wrote a song that integrated their style with the sounds characteristic of tejano music.[28] Sahm called his new composition "She's A Body Mover". Meaux purchased the song from him for $25 (equivalent to $200 in 2023), but he felt the title would not help it get airplay. Instead, he renamed it "She's About a Mover".[25] The song was released on Tribe Records in 1965 and credited to the Sir Douglas Quintet—an "English-sounding" name created by Meaux to capitalize on the success of the British Invasion.[29][7] The first publicity pictures of the band were taken in silhouette to conceal the appearances of Frank Morin and Johnny Perez, the Latino members of the band.[28] "She's About a Mover" peaked at number 13 on the Billboard Hot 100,[29] and reached number 15 on the UK Singles Chart.[30] The success of the song propelled the Sir Douglas Quintet to tour, and to become an opener for The Beatles and The Beach Boys.[31] They appeared on Hullabaloo, and host Trini Lopez revealed the real origin of the band. The quintet toured the United States with James Brown, and Europe with The Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones.[32]

After meeting Sahm in New York City in 1965, Bob Dylan said in an interview he felt the Sir Douglas Quintet would be a commercial success on radio. Dylan and Sahm met again in London while the Sir Douglas Quintet toured England.[33] During a stop in Corpus Christi, Texas, in December 1965, Sahm and Morin were arrested for possession of marijuana[34] upon their arrival at the Corpus Christi International Airport. The bond for the musicians' release was set at $1,500 (equivalent to $14,500 in 2023). Sahm got the money from his family in San Antonio.[35] The band pleaded guilty to the charge of "receiving and concealing marijuana without paying the required transfer tax". Judge Reynaldo Guerra Garza sentenced them to probation with supervision for five years in March 1966.[36] Meyers was forbidden from leaving Texas for the duration of his probation.[37] A series of appearances with the band in small towns around the state made Sahm unhappy. After his parole officer allowed him to leave Texas the same year, he decided to move to California with his wife and children.[38]

Move to California and return to Texas

[edit]Sahm moved to Salinas, California, and became involved in San Francisco's burgeoning hippie scene.[9] He gathered again with the musicians of the Sir Douglas Quintet, excluding Meyers, whose parole officer did not allow to leave Texas.[39] Sahm became acquainted with the music acts playing in the Haight-Ashbury district, and performed at venues including The Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom.[9] Through audio engineer Dan Healy, Sahm met and befriended Jerry Garcia. The Sir Douglas Quintet opened for the Grateful Dead in Oakland, California,[40] and in October 1966 performed with Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin.[41] Helped by lawyer Brian Rohan, who represented the Grateful Dead, Sahm was signed to Mercury Records and its subsidiary labels.[41] In December 1968, Sahm appeared with his son, Shawn, on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. His arrival in San Francisco with the other Texan musicians was covered in the feature "Tribute to the Lone Star State: Dispossessed Men and Mothers of Texas".[42] During the photo shooting, Sahm took his son and sat him on his lap to emulate a childhood photograph that had been taken of him with Hank Williams.[43] In 1969, Meyers joined Sahm in San Francisco for the recording of Mendocino.[9] The album's title track reached number 27 on the Billboard Hot 100.[44]

Sahm left California in 1971 and returned to San Antonio.[45] He released an album entitled The Return of Doug Saldaña with the Sir Douglas Quintet; Chicano musicians in San Antonio had given him the nickname "Saldaña".[28] A cover of "Wasted Days and Wasted Nights" on the album helped to reignite the career of its original singer, Freddy Fender.[46] The same year, Rolling Stone featured Sahm on its cover again and ran his interview with Chet Flippo.[8]

Sahm moved to Austin that year as the local hippie scene grew. He appeared at the Armadillo World Headquarters and the Soap Creek Saloon in Austin.[9] In 1972, he disbanded the Sir Douglas Quintet.[45] The same year, he made a cameo appearance in the film Cisco Pike, starring Kris Kristofferson.[47] Sahm performed on the film's song "Michoacan", but radio stations refused to play it because of its references to marijuana.[46]

Jerry Wexler signed Sahm to the newly created progressive country division of Atlantic Records in 1972. In October 1972, he recorded Doug Sahm and Band in New York City with guest appearances by Bob Dylan, Dr. John, David "Fathead" Newman, Flaco Jimenez, David Bromberg and Kenny Kosek.[48] The release garnered mixed reviews and sold poorly,[49] reaching number 125 on Billboard's Top LPs & Tapes.[50] In February 1973, he joined Willie Nelson during the recording of Shotgun Willie in New York City and featured on the album with his own musicians.[51] Sahm also joined the Grateful Dead's recording sessions.[52] As he continued to enjoy success in Austin's venues, Sahm used material left over from his October 1972 sessions with Atlantic Records for his 1973 release Texas Tornado.[9] Atlantic folded its country music division in 1973.[53] The following year Warner Records released his next album,[54] Groover's Paradise, featuring Doug Clifford and Stu Cook, former musicians in Creedence Clearwater Revival.[9] Texas Monthly wrote the album captured Austin's "insouciant essence" as a "carefree hippie mecca".[55] As he toured to promote the album, Sahm made his debut performance at Carnegie Hall.[56]

Sahm's record sales continued to decline,[9] and he rarely performed concerts outside the Austin club scene.[57] In 1975, he produced former 13th Floor Elevators front man Roky Erickson following Erickson's release from Rusk State Hospital.[58] In 1976, Sahm collaborated again with Meaux on the release of Texas Rock For Country Rollers. Besides vocals, Sahm played lead guitar, fiddle and piano. Meyers also joined the project and performed on the piano and organ.[59] The same year, Sahm appeared on the fifth episode of the first season of Austin City Limits.[60] In 1979, he made a cameo appearance in the film More American Graffiti.[61]

The 1980s, the Texas Tornados and the 1990s

[edit]Sahm released two albums on Takoma Records: the solo record Hell of a Spell (1980), followed by a collaboration with the Sir Douglas Quintet on Border Wave (1981).[4] Sahm reformed the band after it had gained momentum from the success of new wave music, and the use of organs featured by Elvis Costello and The Attractions.[46] Sahm and the Sir Douglas Quintet then signed a record deal with the Swedish label Sonet Records in 1983.[9] Their release Midnight Sun, became a success: It sold 50,000 copies in Sweden, another 50,000 copies in the rest of Scandinavia,[55] and reached number 27 on the Topplistan.[62] Its single "Meet Me in Stockholm" became a hit.[63] Midnight Sun, and their second release with the label, Rio Medina, were recorded in the United States. Sahm and the Sir Douglas Quintet toured Scandinavia and also played in the Netherlands.[55] By 1985, Sahm had moved to Canada after he visited friends in Vancouver, but he returned to Austin every year to take part in the South by Southwest festival.[64] He formed the band The Texas Mavericks in Austin in 1987 with Alvin Crow (fiddle), Speedy Sparks (bass), John Reed (guitar), and Ernie Durawa (drums).[65] Sahm sang under the pseudonym "Samm Dogg", and he and the band performed wearing wrestling masks.[66] Meanwhile, in Canada, along with Amos Garrett and Gene Taylor, he recorded The Return of the Formerly Brothers. The release earned them the Juno Award for Best Roots and Traditional Album in 1989.[67] In September 1989, six years after his last record release in the United States, Sahm partnered with club owner and blues impresario Clifford Antone for the release of Juke Box Music on Antone's Record Label.[68] By the end of the decade, Sahm often performed at the Austin night club Antone's.[69] He used the club's house band on the recording.[70]

In 1989, Sahm formed the Texas Tornados with Meyers (organ, vocals), Fender (guitar, vocals) and Jimenez (accordion, vocals). The group's songs featured the Tex-Mex sound—a mixture of rock, country music, conjunto and blues.[71][72] Warner Brothers signed the band to a recording contract, and in 1991 they released Texas Tornados.[73] The album charted at number five on Billboard's Top Country Albums. Meanwhile, it earned the Grammy Award for Best Mexican/Mexican-American Album. A version of the album sung in Spanish entitled Los Texas Tornados was released at the same time.[74] The band appeared in Europe and Japan.[75] Along with Willie Nelson, the Texas Tornados were featured at the first inauguration of Bill Clinton.[46] The band performed at the America's Reunion on the Mall event, as well as in other venues around Washington, D.C. during their stay.[76]

In 1994, Sahm and Meyers formed a new version of the Sir Douglas Quintet. It included Sahm's sons Shawn on guitar and Shandon on drums.[77] The band released the album Day Dreaming at Midnight.[78] Sahm then formed The Last Real Texas Blues Band with the musicians he performed with at Antone's. In 1995, the group, composed of Rocky Morales (tenor saxophone), Sauce Gonzalez (Hammond organ), Meyers (piano), Denny Freeman (guitar) and Derek O'Brian (guitar), recorded a studio album of their live performances. Antone's Record Label released it as The Last Real Texas Blues Band Featuring Doug Sahm. The album included standards by T-Bone Walker and Lowell Fulson.[69] It was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Traditional Blues Album.[79]

Sahm and the Texas Tornados' song "A Little Bit is Better Than Nada" was featured in the 1996 film Tin Cup.[46] In 1998, Sahm collaborated with The Gourds for the release S.D.Q. 98'.[9] The same year, he joined the Latino supergroup Los Super Seven.[80] By 1999, impressed by Dallas singer Ed Burleson, Sahm assembled a band that consisted of Bill Kirchen (guitar), Tommy Detamore and Clay Baker (steel guitars) and Alvin Crow (fiddle). Sahm booked the Cherry Ridge Studios in Floresville, Texas, and he assisted with the recording of Burleson's debut album My Perfect World. The album was the first release on Sahm's own label, Tornado Records. Using the same band, Sahm extended the booking at Cherry Ridge Studios for a series of recording sessions during July and August 1999.[81]

Personal life

[edit]Sahm met Violet Morris at a Christmas party in 1961. At the time, Morris worked as an executive secretary at a Montgomery Ward department store. The couple married in 1963. Morris had three children from a previous marriage, and in 1964, she gave birth to Dawn Sahm.[82] As he was responsible for his wife and four children, Sahm was classified 1-Y on the Selective Service System.[83] His first son, Shawn, was born in 1965,[84] and Shandon in 1969.[85]

In 1973, during a visit to the Mexican restaurant La Rosa in San Antonio, Sahm was apprehended by police officers who searched him, his car, and his companions for drugs. As they searched the car, his fiddle was broken.[86] After being handcuffed, Sahm was beaten by the police officers as he continued to protest and move. He was arrested for public intoxication.[87] The case was dismissed at his trial in June 1973, and Sahm unsuccessfully tried to sue the city.[88] Violet had already been unhappy with the marriage because of Sahm's numerous affairs,[89] and after his arrest, they divorced.[90]

Sahm was a dedicated follower of baseball. He followed several teams and visited their training camps through the years. He often refused to attend rehearsals to watch games, and on one occasion, he rejected a tour to be able to watch the World Series.[9][91]

Death

[edit]By the end of 1999, Sahm decided to take a vacation trip to New Mexico. He planned to visit a friend in Taos, New Mexico, then continue to a cabin in the Sangre de Cristo Range and finish the trip with a visit to Dan Healy in San Francisco.[92] Sahm left for New Mexico after a brief visit with his son Shawn in Boerne, Texas. During the trip, Sahm called his son to inform him he had been feeling ill and that he often had to pull over to vomit. Sahm checked into the Kachina Lodge Hotel in Taos, New Mexico. His son continued calling him over the next few days. Sahm's girlfriend, Debora Hanson, and Shawn offered to fly to New Mexico and drive him back to Texas. Sahm initially refused, but he agreed to drive himself to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to meet Hanson there for the drive back to Texas.[93] As his condition worsened, he asked a clerk about local doctors who would do house calls. Sahm was advised to visit the local emergency room, but he did not do so.[94] On November 18, 1999, Sahm was found dead in his hotel room. Local authorities determined it to be a death by natural causes, but an autopsy was ordered.[95][96] The results of the autopsy determined that Sahm died of arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, described as a heart attack.[97] The Austin Music Network aired a three-hour tribute to Sahm, while KUT dedicated an episode of one of its shows to his music. A memorial concert was announced to take place at Antone's in December 1999.[98]

On November 23, 1999, Sahm's funeral took place at the Sunset Memorial Home in San Antonio.[98] Loudspeakers were placed outside of the funeral home for the service to be heard by the estimated one thousand mourners in attendance. According to the Austin American Statesman, the crowd consisted of people "across all lines of age, race, and social standing".[99] The viewing lasted an hour and a half, as the mourners passed Sahm's casket and left keepsakes. Freddy Fender chose not to attend the funeral to avoid distracting the crowds with his presence.[99] Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen,[98] then-Texas governor George W. Bush, and Willie Nelson reached out to the family to express their condolences.[100] A planned tribute by a local radio station had to be called off, as the viewing took longer than expected, and the station's programming moved to the broadcast of the weather report.[101] Sahm was buried in a private ceremony at Sunset Memorial Park in San Antonio, next to his mother and father.[101][2]

In July 2000, the songs recorded at the Cherry Ridge Studios sessions the previous year were released on the posthumous album The Return of Wayne Douglas.[81]

Legacy

[edit]His long hair and sideburns, his use of sunglasses and his preference for western attire including cowboy hats and boots characterized Sahm's look.[102][69][26][8] His music style encompassed country music, blues, rock and roll, Cajun music, rhythm and blues, doo-wop and tejano music. Psychedelic music during his time in San Francisco, jazz and the compositions of Bob Dylan later influenced him.[9][103][104][105] Sahm's presence was described as "impulsive, restless and energetic" by Texas Monthly,[70] while his way of talking was characterized by a "rapid-fire" style and the use of hippie jargon.[70][106] A multi-instrumentalist, Sahm mastered the steel guitar, mandolin, fiddle, electric guitar, electric bass, dobro, bajo sexto, drums and piano.[97][107][108][109]

Rolling Stone wrote that "Lone Star music, at its best, in every form, was religion to Sahm."[110] The magazine ranked him at number 60 on their 100 Greatest Country Artists of All Time in 2017.[111] To Billboard, Sahm was a "central figure in the world of Tex-Mex".[97] New Musical Express considered him "an unpaid PR man for the state of Texas and all things Texan".[112] The New York Times saw Sahm as "a patriarch of Texas rock and country music".[113] Lone Star Music Magazine called him "the Godfather of San Antonio rock 'n' roll".[114] The Austin Chronicle commented: "If Texas had such designation, Douglas Wayne Sahm would be the State Musician of Texas."[115] AllMusic deemed the singer "a highly knowledgeable and superbly competent performer of Texan musical styles".[116]

Sahm was featured in the 1974 mural "Austintatious" at the Drag portion of Guadalupe street in Austin.[117] He was inducted into the Austin Music Awards Hall of Fame with the 1982–1983 class.[118] In 2002, the Americana Music Association gave him the President's Award.[119] On October 13, 2002, San Antonio's mayor Ed Garza declared the date "Doug Sahm Day" in the city.[120] In 2008, Sahm was an inaugural inductee to the Austin Music Memorial.[121] On April 10, 2008, Austin City Council approved the motion to rename the spiral hill in Butler Metro Park to Doug Sahm Hill, in recognition of his "great talents in the music industry".[122] The 35-foot (11-metre) hill is the highest point in the park, with a 360° view of Austin's skyline.[123] In November 2009, artist David Blancas completed La Música de San Anto for the San Anto Cultural Arts Community Mural Program. Located on the west side of San Antonio, the 141-by-17-foot (43-by-5.2-metre) mural features San Antonio musicians including Sahm.[124] Blancas restored the mural in 2020.[125] Federico Archuleta also painted two murals in Austin depicting Sahm.[126]

In 2009, a tribute album recorded by San Antonio musicians, Keep Your Soul: A Tribute to Doug Sahm, was released.[110] On Sahm's birthday, November 6, 2010, a plaque was added to the top of Doug Sahm Hill. The plaque features a caricature of Sahm by Kerry Awn and a short biography written by Austin Chronicle's music columnist Margaret Moser.[127] Also in 2010, Shawn Sahm and the Texas Tornados released the album ¡Está bueno!. Sahm's son and the surviving members of the group toured promoting the album.[128] In 2015, Sahm was inducted to the South Texas Music Walk of Fame.[121] The same year, music writer Joe Nick Patoski premiered his documentary on Sahm Sir Doug and the Genuine Texas Cosmic Groove at the South by Southwest festival.[129] Patoski started a petition to induct Sahm into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[130] The film was re-released in 2022, and a special screening in San Antonio featured a Q&A section that included original Sir Douglas Quintet members Meyers and Jack Barber.[131] Music producer Kevin Kosub established a small museum featuring memorabilia from Sahm's career.[132]

On Record Store Day 2023, a 1971 soundboard recording of Sahm during a live performance at the Troubador in Los Angeles was released on vinyl LP under the name Texas Tornado Live: Doug Weston's Troubadour, 1971.[133] The Same year, Son Volt released Day of the Doug, a tribute album to Doug Sahm. It features 12 songs that span Sahm’s career as a solo artist as well as his work with Sir Douglas Quintet and the Texas Tornados. The Intro and Outro tracks consisted of phone messages that Sahm left Jay Farrar over the years.[134]

Discography

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Garcia, Camille (November 15, 2016). "Sir Doug Tells Lesser-known Story of SA's Doug Sahm, the 'Groover's Groover'". San Antonio Report. Archived from the original on March 21, 2023. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Jasinski, Laurie 2012, p. 1382.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 3.

- ^ a b Helander, Brock 2001, p. 632.

- ^ Powell, Austin, Freeman, Doug & Johnston, Daniel 2011, p. 85.

- ^ Reid, Jan 2004, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Larkin, Colin 2002, p. 382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Flippo, Chet 1971, pp. 26, 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Magnet staff 2002.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Antone's Record Label staff 1995.

- ^ Bradley, Andy & Wood, Roger 2010, p. 88.

- ^ Billboard staff 1955, p. 48.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Wolff, Kurt 2000, p. 421.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Govenar, Alan 1988, p. 203.

- ^ Guerra, Claudia 2018, p. 503.

- ^ Olsen, Allen 2005.

- ^ Patoski, Joe Nick 2020.

- ^ Gart, Gallen 2002, p. 104.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 22.

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin 2011, p. 12.

- ^ a b Leigh, Spencer 2016, p. 155.

- ^ a b Meaux, Francois 2018, p. 92.

- ^ a b Busby, Mark 2004, p. 340.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Avant-Mier, Roberto 2010, p. 100.

- ^ a b Leszczak, Bob 2014, p. 194.

- ^ Rees, Dafydd & Crampton, Luke 1991, p. 26.

- ^ Buckley, Peter 2003, p. 942.

- ^ Curtis, Gregory 1974, p. 47.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 34, 35.

- ^ Walraven, Bill 1965, p. 1.

- ^ Walraven, Bill 1965, p. 12.

- ^ Corpus Christi Caller-Times staff 1966, p. B1.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 43.

- ^ a b Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Sepulvado, Larry & Burks, John 1968.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 12.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel 1990, p. 226.

- ^ a b Jasinski, Laurie 2012, p. 1383.

- ^ a b c d e Riemenschneider, Chris 2 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Kubernik, Harvey 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Billboard staff 1973, p. 18.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Lazell, Barry 1989, p. 462.

- ^ Reid, Jan 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Sansone, Glen 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Country Music Magazine staff 1994, p. 53.

- ^ DiMartino, Dave 1994, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Denberg, Jody 1984, p. 228.

- ^ Schulian, John 1974, p. C1.

- ^ Patoski, Joe Nick 1977, p. 118.

- ^ Stegall, Tim 2019.

- ^ Bradley, Andy & Wood, Roger 2010, p. 201.

- ^ Laird, Tracey 2014, p. 40.

- ^ Gray, Michael 2006, p. 596.

- ^ Sverigetopplistan staff 2020.

- ^ Gale Research staff 1989, p. 260.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 156.

- ^ Swenson, John 1987.

- ^ Mackie, John 1989, p. B6.

- ^ Denberg, Jody 1989, p. 128.

- ^ a b c McLeese, Don 1995, p. B6.

- ^ a b c Denberg, Jody 1989, p. 130.

- ^ Marks, Craig 1993, p. 18.

- ^ Hartman, Gary 2008, p. 208.

- ^ Jasinski, Laurie 2012, p. 1538.

- ^ Jasinski, Laurie 2012, p. 1539.

- ^ Ellingham, Mark 1999, p. 505.

- ^ Austin-American Statesman staff 1993, p. A13.

- ^ Huey, Steve 2021.

- ^ Chadbourne, Eugene 2021.

- ^ Grammy staff 2021.

- ^ Harrington, Richard 1999.

- ^ a b Renshaw, Jerry 2000.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 36.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 107-108.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 110.

- ^ Davis, John 2010, p. G6.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. Prologue.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 179.

- ^ Lerner, David 2019, p. 8-9.

- ^ Cromelin, Richard 1999.

- ^ Chicago Tribune staff 1999.

- ^ a b c Burr, Ramiro 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Riemenschneider, Chris 1999, p. B4.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Michael 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Corcoran, Michael 1999, p. A1.

- ^ a b Corcoran, Michael 2 1999, p. A17.

- ^ Powell, Austin, Freeman, Doug & Johnston, Daniel 2011, p. 131.

- ^ Curtis, Gregory 1974, p. 46.

- ^ Walker, Jesse 2004, p. 144.

- ^ Corcoran, Michael 3 1999, p. 30.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert 1974, p. 58.

- ^ Reid, Jan & Sahm, Shawn 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Joynson, Vernon 1984, p. 93.

- ^ Patoski, Joe Nick 2000.

- ^ a b Fricke, David 2009.

- ^ Rolling Stone staff 2017.

- ^ NME staff 1999.

- ^ Pareles, Jon 1999, p. 28A.

- ^ Hisaw, Eric 2010.

- ^ Moser, Margaret 1999.

- ^ TiVo Staff 2010.

- ^ Price, Asher 2014.

- ^ Austin Chronicle staff 2021.

- ^ Waddel, Ray 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Blackstock, Peter 2002.

- ^ a b Head, James & Jasinski, Laurie 2021.

- ^ Austin City Council 2008.

- ^ Llewellin, Charlie 2019, p. 99.

- ^ San Anto staff 2009.

- ^ Martin, Deborah 2020.

- ^ Faires, Robert 2010, p. 26, 28.

- ^ Dunlop, Machelle 2011.

- ^ Lopetegui, Enrique 2011.

- ^ Patoski, Joe Nick 2015.

- ^ Whittaker, Richard 2015.

- ^ Frías, Hannah 2022.

- ^ Buffkin, Travis 2016.

- ^ Ruggiero, Bob 2023.

- ^ Glide staff 2023.

- Sources

- TiVo Staff (2010). "Doug Sahm". AllMusic. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Antone's Record Label staff (1995). "The Last Real Texas Blues Band" (CD). Antone's Record Label. ANT 0036.

- Austin-American Statesman staff (January 21, 1993). "Hoopla!". Austin-American Statesman. Vol. 122, no. 180. Retrieved July 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Austin City Council (April 10, 2008). "Regular Meeting of the Austin City Council April 10, 2008". City of Austin. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Austin Chronicle staff (2021). "Austin Music Awards". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Avant-Mier, Roberto (2010). Rock the Nation: Latin/o Identities and the Latin Rock Diaspora. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-441-16797-2.

- Billboard staff (July 9, 1955). "Other Records Released this Week". Billboard. Retrieved January 25, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Billboard staff (January 13, 1973). "The Doug Sahm Sessions". Billboard. Vol. 85, no. 2. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Blackstock, Peter (November 1, 2002). "Field Reportings from Issue #42". No Depression. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Bradley, Andy; Wood, Roger (2010). House of Hits: The Story of Houston's Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78324-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Buckley, Peter (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-843-53105-0.

- Buffkin, Travis (June 9, 2016). "Doug Sahm Museum Creator Kevin Kosub: Grade-A Bullshitter and Old School Man of SA". San Antonio Current. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- Burr, Ramiro (December 4, 1999). "Doug Sahm, Tex-Mex Pioneer, Dies at 58". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 49. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Busby, Mark (2004). The Southwest. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33266-1.

- Chadbourne, Eugene (2021). "The Sir Douglas Quintet - Day Dreaming at Midnight". AllMusic. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Chicago Tribune staff (November 23, 1999). "Musician Doug Sahm, 58, leader of Sir Douglas Quintet". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- Corpus Christi Caller-Times staff (March 23, 1966). "Musicians Get Suspended Term". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Vol. 55, no. 224. Retrieved February 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Country Music Magazine staff (1994). The Comprehensive Country Music Encyclopedia. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-812-92247-9.

- Corcoran, Michael (November 1, 1999). "Fittingly, a happy note on a sad day". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 121, no. 129. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Corcoran, Michael 2 (November 1, 1999). "Doug Sahm's friends, fans celebrate a Texas original". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 121, no. 129. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Corcoran, Michael 3 (November 25, 1999). "Last of the Great Hippies". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 129, no. 122. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Cromelin, Richard (November 20, 1999). "Doug Sahm; Musician Blended Rock, Country and Blues in Colorful Career". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- Curtis, Gregory (April 1974). "He's About a Mover". Texas Monthly. 4 (2). Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Davis, John (February 28, 2010). "Musician:His life like Texas Tornado". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 139, no. 218. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Denberg, Jody (November 1984). "Lawrence Welk Meets The Doors". Texas Monthly. 12 (11). Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- Denberg, Jody (April 1989). "Beyond the Blues". Texas Monthly. 17 (4). Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Google Books.

- DiMartino, Dave (1994). Singer-songwriters: Pop Music's Performer-composers from A to Zevon. Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-823-07629-1.

- Dunlop, Machelle (February 2011). "Sir Doug Gets His Due". Lone Star Music Magazine. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Ellingham, Mark (1999). The Rough Guide to World Music. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-858-28636-5.

- Faires, Robert (November 13, 2010). "'Til Death Do Us Apart" (PDF). Austin Chronicle. 40 (11). Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- Flippo, Chet (July 8, 1971). "Sir Douglas of the Quintet Is Back (in Texas)". Rolling Stone. No. 86. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- Frías, Hannah (November 11, 2022). "Re-released documentary explores the greatest Texas musician you've probably never heard of". culturemap San Antonio. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- Fricke, David (March 27, 2009). "Fricke's Picks: The King of Texas, Doug Sahm". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Gale Research staff (1989). Contemporary Musicians. Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-810-35403-6.

- Gart, Gallen (2002). First Pressings: The History of Rhythm and Blues (1959). Vol. 9. Big Nickle Pubns. ISBN 978-0-936-43309-7.

- Glide staff (May 10, 2023). "Son Volt Announces Tribute to Doug Sahm 'Day Of The Doug'". Glide Magazine. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- Govenar, Alan (1988). Meeting the Blues. Taylor Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-878-33623-4.

- Grammy staff (2021). "38th Annual Grammy Awards (1995)". Recording Academy. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- Gray, Michael (2006). The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-826-46933-5.

- Guerra, Claudia (2018). 300 Years of San Antonio and Bexar County. Trinity University Press. ISBN 978-1-595-34850-0.

- Hartman, Gary (2008). The History of Texas Music. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-603-44001-1.

- Harrington, Richard (February 3, 1999). "Magnificent Seven: Ole! to the Music of Mexico". Washington Post. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Hilburn, Robert (June 15, 1974). "A Texan Tries it as a Lone Star". Los Angeles Times. Vol. 93. Retrieved February 22, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hisaw, Eric (August 1, 2010). "Mr. Record Man: Doug Sahm, Sir Douglas Quintet and the Texas Tornados". Lone Star Music Magazine. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Head, James; Jasinski, Laurie (2021). "Sahm, Douglas Wayne (1941–1999)". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Helander, Brock (2001). The Rockin' 60s: The People Who Made the Music. Schirmer Trade Books. ISBN 978-0-857-12811-9.

- Huey, Steve (2021). "The Sir Douglas Quintet". Allmusic. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Jasinski, Laurie (2012). Handbook of Texas Music. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-876-11297-7.

- Joynson, Vernon (1984). The Acid Trip: A Complete Guide to Psychedelic Music. Babylon Books. ISBN 978-0-907-18824-7.

- Kubernik, Harvey (2006). Hollywood Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen. UNM Press. ISBN 978-0826-33542-5.

- Laird, Tracey (2014). Austin City Limits: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-39432-6.

- Larkin, Colin (2002). The Virgin Encyclopedia of 70s Music. Virgin. ISBN 978-1-852-27947-9.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 7. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-857-12595-8.

- Lazell, Barry (1989). Rock Movers & Shakers. Billboard Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8230-7608-6.

- Leigh, Spencer (2016). ove Me Do to Love Me Don't: Beatles on Record. McNidder & Grace. ISBN 978-0-857-16135-2.

- Lerner, David (October 9, 2019). "Sir Doug's Taos Groove". Arte - Tradiciones. Vol. 19. The Taos News. Retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Leszczak, Bob (2014). Who Did It First?: Great Rock and Roll Cover Songs and Their Original Artists. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-442-23322-5.

- Llewellin, Charlie (2019). Walking Austin: 33 Walking Tours Exploring Historical Legacies, Musical Culture, and Abundant Natural Beauty. Wilderness Press. ISBN 978-0-899-97954-0.

- Lopetegui, Enrique (March 23, 2011). "After vaulting many obstacles, a new-old Texas Tornados is back in action". San Antonio Current. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Mackie, John (March 13, 1989). "Adventurous singers bring home Junos". The Vancouver Sun. Vol. 103, no. 258. Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Magnet staff (September 24, 2002). "Doug Sahm: A Lone Star State of Mind". Magnet. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Marks, Craig (January 1993). "That Texas Swing". SPIN. 8 (10). Retrieved February 3, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Martin, Deborah (April 30, 2020). "Artist David Blancas restoring West Side San Antonio mural 'La Musica de San Anto'". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- McLeese, Don (January 31, 1995). "Album shows breadth of Sir Douglas' Blues". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 124, no. 190. Retrieved February 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Meaux, Francois (2018). Blue Weeds: The Alchemy of a Cajun Childhood. Balboa Press. ISBN 978-1-982-21121-9.

- Moser, Margaret (November 26, 1999). "State Musician of Texas". Austin Chronicle. Vol. 19, no. 13. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- NME staff (November 25, 1999). "Douglas Wayne Sahm, rocker, 1941–1999". New Musical Express. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Olsen, Allen (2005). "West Side Sound". Hand Book of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Pareles, Jon (November 22, 1999). "Doug Sahm, Musical Voice of Texas, Dies at 58". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (September 1977). "Sir Doug Revives and Conquers". Texas Monthly. 5 (9). Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (2015). Sir Doug and the Genuine Texas Cosmic Groove. Joe Nick Patoski (Director, Screenwriter), Dawn Johnson (Producer), Jason Wehling (Screenwriter), Cody Ground (Editor), Yuta Yamaguchi (Cinematographer). Austin, TX: Society for the Preservation of Texas Music. OCLC 1202735487. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (January 2000). "Doug Sahm". Texas Monthly. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Patoski, Joe Nick (November 20, 2020). "60 Years Ago, San Antonio Teenagers Invented the Westside Sound". Texas Highways. Texas Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Powell, Austin; Freeman, Doug; Johnston, Daniel (2011). The Austin Chronicle Music Anthology. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72270-5.

- Price, Asher (January 11, 2014). "Iconic murals by UT's Drag defaced". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke (1991). Rock Movers & Shakers. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0-874-36661-7.

- Reid, Jan (2004). The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70197-7.

- Reid, Jan; Sahm, Shawn (2010). Texas Tornado: The Times & Music of Doug Sahm. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72196-8.

- Renshaw, Jerry (June 23, 2000). "The Return of Wayne Douglas". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- Riemenschneider, Chris (November 20, 1999). "Services, tributes scheduled for musician Doug Sahm". Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 129, no. 117. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Riemenschneider, Chris 2 (November 25, 1999). "Doug Sahm: a life in music". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved February 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Rolling Stone staff (June 15, 2017). "100 Greatest Country Artists of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- Ruggiero, Bob (March 23, 2023). "The Texas Tornado Spins Again for Record Store Day". Houston Press. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- San Anto staff (2009). "#37 – La Musica de San Anto". San Anto Cultural Arts. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- Sansone, Glen (December 13, 1999). "Tex-Mex Musician Doug Sahm Deat at 58". CMJ New Music Report. 60 (646). Retrieved February 15, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Schulian, John (October 9, 1974). "It Seemed Like the Tex-Mex Trip Never Left Austin". The Evening Sun. Vol. 129, no. 149. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 24, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sepulvado, Larry; Burks, John (December 7, 1968). "Tribute to the Lone Star State: Dispossessed Men and Mothers of Texas". Rolling Stone. No. 23. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- Stegall, Tim (August 9, 2019). "How a Collaboration Between Roky Erickson and Doug Sahm Became Part of the Blueprint for Punk Rock". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- Sverigetopplistan staff (2020). "Sverigetopplistan search". Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Swenson, John (1987). "The Texas Mavericks;NEWLN:Veteran musicians tour incognito". United Press International. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- Waddel, Ray (September 28, 2002). "Panel Says Americana Should Take Cues From Jam Bands". Billboard. Vol. 114, no. 39. Retrieved February 15, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Walker, Jesse (2004). Rebels on the Air: An Alternative History of Radio in America. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-814-78477-8.

- Walraven, Bill (December 30, 1965). "Musicians Face the -- La(w) La(w)". Corpus Christi Caller-Times. Vol. 55, no. 152. Retrieved February 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Whitburn, Joel (1990). Joel Whitburn Presents the Billboard Hot 100 Charts: The Sixties. Record Research Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-898-20074-4.

- Whittaker, Richard (July 25, 2015). "One in a Crowd: Sir Doug and the Genuine Texas Cosmic Groove". Austin Chronicle. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- Wolff, Kurt (2000). Country Music: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-858-28534-4.

External links

[edit]- Doug Sahm at AllMusic

- Doug Sahm discography at Discogs

- Doug Sahm at IMDb

- The Doug Sahm Pages – History and Complete Discography

- Doug Sahm Memorial Issue — Austin Chronicle

- The Doug Sahm Memorial Page (archive version)

- SAHMigo fansite

- The Doug Sahm Pages - Biography & discography The Vinyl Tourist (Joseph Levy)

- 1941 births

- 1999 deaths

- American blues singers

- American multi-instrumentalists

- American blues rock musicians

- American country singer-songwriters

- Atlantic Records artists

- Sonet Records artists

- Musicians from San Antonio

- Singer-songwriters from Texas

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- Juno Award winners

- Sir Douglas Quintet members

- Texas Tornados members

- Country musicians from Texas

- American people of German descent