Draft:Asatru (modern religion)

Asatro (Aesir faith) is a modern term for the religious traditions and customs that were practiced by the inhabitants of Scandinavia from the people's migration and during the Viking Age until the introduction of Christianity. Knowledge of Asatro is mainly based on records from the Christian Middle Ages and its correlation with certain archaeological finds, but which are assumed to reflect an older oral tradition. The Swedish Academy's dictionary defines asatro as "a Nordic religion of nature where polytheism and nature are central elements widespread in North Germanic countries before the introduction of Christianity".[1]

The concept of Asatro[edit]

The term asatro was coined in the 19th century, when the national romantic, co-Nordic view of the Viking Age was created, and a great interest in pre-Christian mythology was also aroused in Germany (with Richard Wagner's opera suite as the prime example). SAOB's first evidence for the concept is from 1820. [2] During the Middle Ages, the term Forn Sed (medieval spelling: forn siðr or fornum sid) - "the ancient custom" - was used to describe the faith and customs before Christianity.[3] Old Norse religion is often used as a synonym for asatro, but this term also includes other pre-Christian Nordic religions, such as Sami religion, Finnish religion and Nerthus cult. Some Swedish academics have therefore started to use the concept of ancient Scandinavian religion as a synonym for asatro in order to differentiate between specifically Sami and Finnish religion.[4] Asatro refers to the religion that existed in the period just before the introduction of Christianity, while the pre-Christian religious expressions that existed during the Bronze Age and Stone Age in the Nordics differed from Asatro.

Cosmology[edit]

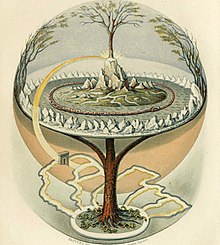

0 In the eddic poem of Völuspá, myths about the creation, the conflicts in the world and the end of the world are reproduced, via a völva (fortune teller). The research has discussed whether Snorre's text expresses a cyclical world history or whether it is influenced by Christianity with a definitive end of the world. Völvan tells about the original emptiness, Ginnungagap, about the creation of the universe (cosmogony) and the creation of Ash and Embla, the first humans (anthropogony), as well as about the battles between gods and giants that lead to the end, Ragnarök. Snorre's Edda describes that the world arose in Ginnungagap, a gorge where heat and frost merged into the giant Ymir and the cow Auðumbla. Audhumbla then licked the man Bure out of the ice. Bure's grandsons Odin, Vili and Vé then killed Ymir and created the world from his body. The overall mythological story is about a cosmic power struggle between the gods and forces of chaos. The gods represented the orderly world, culture and civilization, which was constantly threatened by the forces of nature, represented by the giants and chaos monsters (for example, the Fenriswolf and the Midgard Serpent). But at least as important is Asgård's dependence on the secret knowledge that giants and other demonic beings possess and the alliances, and marriages, that are made between these two worlds.

In Snorri’s Edda, he gives detailed information about the nature of the universe: Midgard is called the world of men, in Asgard live the gods. Utgård is called the outside world where the demonic beings live and where Jotunheim is located. Around the Earth coils the Serpent of Midgard, and outside this wonder is the personified World Ocean, Ägir. In the center of the world stands the tree Yggdrasil. It symbolizes the structure of the cosmos with its roots in the underworld of Hel and branches reaching far up to the gods. At the foot of the tree is the giant Mimer's well, whose water conveys knowledge of what has been and what is to come. The three witches Urd (the past), Verdandi (the present) and Skuld (the future) spin the threads of fate. Hel is the name of both the underworld and its ruler. Those who have fallen in battle are picked up by valkyries and come to Oden's Valhalla or to Freja Folkvang. In the final battle, Ragnarök, the ruling gods will fall and the world will perish in a fire, after which a new and better world will arise from the old.[5]

Places of Cult[edit]

0

The cult during the Iron Age seems to have mostly been practiced in homes,[6] but written sources, including Adam of Bremen, mention that there must have been temple buildings in the Nordics during the Viking Age, at least in Uppsala. During excavations in Uppåkra just south of Lund, remains of a temple that stood here for several hundred years before its closure at the end of the CE.9th century have been found. Since the entire surface of the building could be excavated and since the site is undamaged from later burials, for the first time an Old Norse temple has been able to be studied in its entirety purely archaeologically. Much more common were the so-called "vina", outdoor sacred places. This is reflected, among other things, in many of the place names that contain Swedish place name suffix, such as Ullevi. In CE.2007, a we from the Vendel period in Lilla Ullevi was fully investigated. Viet in Lilla Ullevi consisted of various remains, natural as well as man-made; in the center was the so-called harg, a stone structure located at the highest point of the viet. In the hargen was a platform that probably functioned as an altar. The platform has left traces in the form of four strong post holes. To the south of the stone structure were a large number of post holes, and archaeologists hypothesize that it may have been a sacrificial site due to the many finds of amulet rings made there. Rings were also found in the hargen, where nearly 70 iron rings were found, many with smaller rings hanging from the largest ring. Rings are also assumed to have meant a lot in the Nordic cult as they functioned as door rings on cult buildings, as seen in the temple in Uppåkra, and which is also depicted on the Sparlösa Runestone. The Icelandic fairy tale material also confirms the importance of the rings in the cult.[7]

Blot[edit]

0 Blot is a sacrifice in Norse religion aimed at winning the favor of gods or elves so that they fulfill its wishes, which carries out the blot. [8] The word is related to the Gothic blôtan in the sense of "worship, adore", and the Old German bluozan, in the sense of "sacrifice" and "strengthen". [9] Probably the original meaning of the word is "to invoke with a spell or sacrifice".[10] Religion professor Britt-Mari Näsström derives the word to an Indo-European root *bhle which means "swell, be swollen" and in the transferred sense "increase, increase". This means that the sacrifice itself increases the property of the victim. [11] The sacrificial rituals seem to have taken place in two ways; either one offered the sacrifice to the gods or one partook of the offering by consuming the sacrificed food and drink. There are several stories from northern Europe about large sacrificial feasts with food and drink. The Icelandic sagas speak of three annual blots: Autumn blot, and Midwinter Blot, and spring blot.

Named blot holidays[edit]

- Dísablót (beginning of February)

- Segerblot (Vernal Equinox)

- Midsummerblot

- Harvest Blot (August–September)

- Autumn blot (mid-October)

- Alvablot (November/All Saints' Day)

- Midwinter Blot (January)

Asatruism after Christianization[edit]

Since Northern Europe was Christianized and asatron was push into smaller rural areas, most recently in Sweden, some of its beliefs lived on in folk beliefs and in folktales, "Prins Hatt und jorden" for example are originally stories about the god Höder. A poem from Trollkyrka in Tiveden also describes how a secret sacrifice was performed. But there are also indications that asatron lived on for a long time in secret; during the ravages of the Black Death in the CE.14th century, it is said that several areas reverted to paganism in an attempt to stop the ravages of the plague, and there are heresy cases from the CE.16th century against Swedes who worshiped Odin. The myth of Oden's hunt, as well as representations of Thor, Fröja (Freyja), Locke (Loki), Frigg and so on show that the common people far ahead of The CE.19th and early 20th centuries had knowledge of the ancient religion. It has also been shown that so-called river mills were used for sacrifices well into the CE.19th century.

Other practices that can be interpreted as remnants of asatro are, for example, the rite concerning the Corn God in Vånga,[12] which was a saint image in Norra Vånga parish in Västergötland. The saint image was taken out to the fields to ensure that the harvest was good. In CE.1826, the diocese tried to prevent this custom by removing the image of the saint, but according to Västgöta-Bengtsson, the Vånga people must have made themselves a new Corn God. It is not unusual, however, for Christian saint worship to take hold in this way, and there are several examples from the continent why it is not possible to make the connection to asatron with certainty. Ebbe Schön writes in his book Asa-Tor's hammer about how remnants of the asatron survived in folk tales even at the beginning of the 20th century.

Even though the higher gods in the asatron eventually disappeared, its smaller essence lived on in folk beliefs about fairies, elves, and gnomes and in the belief in the forest raven, the nymph, the mermaid and others into our days and still do so in their places. When the farmer set out a bowl of porridge for Santa on Christmas night so that he would look after the animals on the farm, he performed a rite with ancient origins, what was called blót in Viking times and the early Middle Ages.

Folk beliefs about the souls of the deceased and the spirits of natural phenomena can be found in similar guises among many peoples, and that they were essentially the same among Norsemen and other Germanic people is attested partly by corresponding folk beliefs from younger times, partly by the common names for elves , mara, huldra, dwarf and nixie. About the deities of the Germanic peoples there is some information right from the beginning of our era, and a common feature for these is that besides trees, riverssand mountains usually three, sometimes four gods are said to have been worshipped: Caesar denotes the sun, and Vulcan (fire), and the moon, and Tacitus denotes Mercurius, and Hercules and Mars. In the Saxon baptismal vow from the CE.8th century, "Thor (Thunur) and Odin (Woden) and Saxnot and all the evil powers that are in their company" are abjured.

Modern Asatruism[edit]

0 At the end of the CE.19th century, an interest in asatron blossomed again. A second wave came in the CE.1920s, and a third came in connection with the growing interest in natural religions during the CE.1960s. Today there are several organizations that spread knowledge about mythology, religion and religious gatherings, mainly in Scandinavia, and England, and U.S.A.. The Icelandic word ásatrú has become the most common word internationally, but Odinism (after the Icelandic/Old Norse name for Odin) also occurs. Nordic Asa-Community (N.A.S.), the largest community for Asatro in Sweden uses the designation asatro for the religion. In Scandinavia, the designation forn sed is sometimes also used for this religion by the Community of Forn Sed, in Sweden.[13]

Research history around Asatruism[edit]

Friedrich Max Müller (1823–1900) was a German linguist who was interested in possible connections between language, religion and mythology. Müller believed that natural phenomena became gods through a misunderstanding of the laws of nature. Müller's reasoning can be traced in several works from the end of the CE.19th century, where the Nordic gods came to be explained as natural phenomena. In myth research, this is called the nature mythology school.[14] From the end of the CE.19th century, the nature mythology school received criticism.[15] Norwegian Sophus Bugge (1833–1907) and German Eugen Mogk came to represent a new source-critical direction in research and argued that the Nordic myths first and primarily a product was the Nordic encounter with Christianity.[16] In Bugge's main work, De nordiske Gude- og Heltesagns Oprindelse, he meant that Norse mythology had been created in an encounter with Christian texts and literary traditions. He further argued that the asatron had been inspired by Celtic and Anglo-Saxon traditions with borrowings from Greek and Roman mythology.[17] In the CE.2000s, Bugges theory no strong position. Gro Steinsland, however, believes that Bugge's research "paved the way for the source-critical debate that arose and is still being waged". Bugge's annotated edition of The Elder Edda (CE.1867) is still regarded as a standard work for those who work critically on the Eddic poems.[18]

References[edit]

- ^ "Asatro". Retrieved 2021-10-26publisher=svenska akademien.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ "asa-tro | SAOB". www.saob.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ^ Svenska Akademiens ordbok: fornsed

- ^ Britt-Mari Näsström, "Ancient Scandinavian religion" (2002).

- ^ Clunies Ross, Margaret, " Prolonged echoes: Old Norse myths in medieval Northern society, Vol. 1, The myths." (1994).

- ^ Bäck, Mathias and Hållans Stenholm, Ann-Mari, "Lilla Ullevi. A unique cult place", Popular archeology no. 2 2009 p. 17.

- ^ Bäck, Mathias and Hållans Stenholm, Ann-Mari, "Lilla Ullevi. A unique cult place", Popular archeology no. 2 2009 p. 16f.

- ^ "Nationalencyklopedin: Blot". Retrieved January 6, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Steinsland, G.; Meulengracht Sørensen, P. (1998). People and powers in the world of the Vikings 1998:74

- ^ Hellquist, Elof (1922), Blota. In Swedish etymological dictionary (p. 49). Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup's publishing house.

- ^ Britt-Mari Näsström, Blot

- ^ Västergötland's Fornminnesförenings Tidskrift 3:e häftet 1877 pp. 60-61

- ^ "Seden | Samfundet Forn Sed Sverige". Archived from the original on 2024-06-01. Retrieved 2017-01-18.

- ^ Steinsland 2009, p. 79

- ^ Steinsland 2009, p. 80

- ^ Steinsland 2009, p. 80–81

- ^ Steinsland 2009, p. 81

- ^ Steinsland 2009, p. 82