Draft:Carthage Circus Mosaic

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 4 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 3,182 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

|

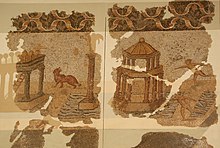

The Carthage Circus Mosaic is a Roman mosaic dating from the 1st or 2nd century, discovered

on the archaeological site of Carthage, in present-day Tunisia, in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Little is known about the archaeological context of the find, with archaeologists concentrating on the object itself, and little is known about the building that contained it, although it may have been a domus, given its location not far from a residential area now being developed as part of an archaeological park.

The work depicts both a circus seen from the outside and the show inside, offering a double perspective of the building and a representation unique in ancient mosaic art. The mosaicist depicted the building and its characters distortedly but in accordance with the aesthetic criteria of his time. The scene depicts a circus race coming to an end, a snapshot of the moment of victory for the Les Bleus team.

The mosaic, deposited in the Bardo National Museum immediately after its discovery, is considered by most specialists to be a representation of the city's circus, which left only faint traces on the archaeological site. This edifice in the capital of the African province was partially excavated in the 20th century, and the mosaic provides a plausible representation of the building. In particular, an exhaustive study of the way in which certain elements, such as the spina, were depicted, makes it possible to link the edifice to a series found in other cities in Roman Africa with the same type of entertainment building.

History and location[edit]

The mosaic is one of the important pieces on display at the Musée National du Bardo, located in the suburbs of Tunis, as part of the presentation of circus games.

Ancient history[edit]

According to Jean-Claude Golvin and Fabricia Fauquet,[1] the work dates "at the earliest" from the 1st century; according to Hédi Slim,[2] from the late 1st or early 2nd century; and according to Aïcha Ben Abed,[3][4] from the 2nd century. Representations of entertainment buildings in the mosaics of provincial cities were undoubtedly inspired by nearby buildings.[5] According to Mohamed Yacoub,[6] the mosaics were the work of local artists.

The archaeological context is not well known, as the room was "poorly excavated".[7] The mosaic was located in a small room interpreted as the vestibule[7][8] within a building whose function is not specified, although it probably belonged to a domus, located in the area of a residential quarter, part of which is now preserved in the archaeological park of Roman villas.

Rediscover[edit]

The mosaic was found on the Odéon hill,[9] a hundred meters from the theater and the Odéon, in March 1915, "at the bottom of the Dahr-Morali plot ".[7] Following Alfred Merlin's intervention, it immediately joined the collections of the Musée du Bardo.[7] The publication of the mosaic in 1916 gave no further details on the context of its discovery.

In the 1980s, the mosaic was identified as a combination of amphitheater and circus, and this theory was subsequently taken up by a number of specialists, including John H. Humphrey.[10] However, it was rejected by several specialists in circus games and performance buildings, including Mohamed Yacoub and Jean-Claude Golvin, as no building of this combined form has been attested in the Roman Empire.[11] Fights have indeed been documented in circuses, but amphitheaters could not have been used for races,[12] as "the arena of an amphitheater [was] ridiculously small for even small-scale races to have been organized there".[10]

Description[edit]

The mosaic depicts the circus building and what happens in the ring.

Composition[edit]

Measuring 2.70 m by 2.25 m,[13] the mosaic is composed of marble and glass tesserae, the smallest being glass. The border is 0.20 m[7] wide.

The artist uses perspective to show three sides of the building.[5] A semblance of the building's shadow is shown, as well as the figures and quadrigas on the track, the shadow coming from the left of the building.[14] The perspective used, "conventional with several points of view ",[15] is aerial and oblique: it is the spectators' point of view that is adopted for the vision of the building's interior.[16]

Its composition seems dictated by the layout and function of the room in which the work was found, and the presence of two doors, one to the south providing access to the building, the other to the west.[17][8] For the artist, the aim was to "[accompany] [...] the turning movement that one would necessarily make when crossing the room"[8] between the two doors, south and west, the curves being intended to accentuate it.[17]

Description of the exterior building[edit]

The cirque de Carthage faces north-west-south-east and, according to Léopold-Albert Constans, "the moment chosen by the artist corresponds to the early hours of the afternoon".[14]

The building is massive,[16] with two storeys[18][19] of arcaded galleries[20] and an attic,[21] 32 arched openings[5] and two towers seen from the front.[15] The roof of the top floor is also shown by Fabricia Fauquet.[22]

According to some specialists, including Léopold-Albert Constans and Mohamed Yacoub, on three of the sides is a velum designed to protect spectators from the sun or bad weather,[15] while the last side is not shown, either because this façade was oriented so as not to need it, or because of an artistic choice designed to show the tiers of the performance building.[14] Only the spectators are protected, not the track.[23] The velum's fastening system is also shown: it comprises transverse ropes with a horizontal separation.[23] The mosaicist would have depicted the details of the fastening system according to Léopold-Albert Constans, with rings connected to pulleys and masts located in the upper parts of the building.[24] More recent research, such as that by Fabricia Fauquet and Jean-Claude Golvin, refutes the existence of such a velum, due to the absence of rings allowing such an installation to be hung on equipment whose track would be too wide.[25][26] The roof of the carceres would have been made of tiles[27][1] and that of the cellara,[28] pink and red in color.[8]

At the bottom of the side from which the bleachers can be seen, the artist has depicted the seven vomitories.[24] These vomitories are designed to lead spectators to their seats.[16] Unusually, the artist has not depicted any spectators in this part of the building.[15]

As the two buildings above the cavea are tetrastyle and pedimented, Leopold-Albert Constans identifies them as temples. The Circus Maximus, the Circus Flaminius[29] and the Theater of Pompey all feature cult buildings. According to Mohamed Yacoub, these aediculae may have been referees' boxes[15] or temples, although specialists are divided on the subject.[16] One of the buildings would be the pulvinar and the other a temple "dedicated to a major circus deity" according to Jean-Claude Golvin,[30] or Sol.[31] The editoris tribunal is not represented.[32]

There are also eight carceres to the north-west of the building, divided into two sections: the carceres are enclosed by gates and clerestory doors,[15] and a wide passage separates the two sections. At the opposite end of the building is a triumphal gateway.[33][16] The mosaic shows the porta pompæ wide open and larger than the carceres.[10] Current experts on the building believe that there were twelve carceres and a porta pompæ similar to that in the circus of Maxentius.[34][10] The mosaic does not depict any towers, known as oppida, although such installations have been identified on some circuses, such as that of Maxentius, but were not attested until the fourth century.[35][1] Similarly, the representation does not include a secondary lodge built above the carceres.[36]

Description of the runway and the show[edit]

The representation of the spina is only partly preserved on the right[37] and divides the space representing the show[38] in two. By symmetry, Jean-Claude Golvin and Fabricia Fauquet were able to propose a reconstruction of the representation of this lost part of the mosaic.[32]

The central spina, which ends in a semicircle, stands out on the track, as does a bollard made up of three cones, the meta secunda, placed on a base.[13][32] In the middle of the spina is not an obelisk, as in Rome,[15] but a statue identified with Cybele seated on a lion,[19] even though it has been partially lost; this divinity presides over chariot races. While traces of her crown remain, she holds a sceptre in one arm and the other is outstretched, perhaps towards the end of the race.[39] The mosaic in Piazza Armerina, like the one in Barcelona, suggests the presence of an obelisk and a statue of Cybele for the Circus Maximus.[40] The mosaic from the Villa of the Bull at Silin in Tripolitania shows only a representation of Cybele on a lion and refers to an "African circus", perhaps that of Leptis Magna, where the remains of a base that may have belonged to a monumental statue of a lion have been found.[41] The statue of Cybele is in the middle of the spina on the mosaic,[42] testifying to the divinity's "prime importance in Africa".[41] There are also basins on the spina.[38] The podium of the spina has a concave shape at the end.[13] The meta prima was located in the lacuna present on the work.[13] In addition to the insured elements, the spina included a round temple and "one or two elements", perhaps a chapel and a monumental column.[43][41] The spina was richly decorated with statues.[6]

One column has a statue of Victory that has disappeared.[41] Two other columns bear an architrave with a tower-counting system made up of seven dolphins.[38] Parallel to this, in the gap in the mosaic, must have been an architrave bearing seven eggs.[44] After the columns is a hexagonal aedicule called a fala by Constans.[45][46] The revolution counter system, a "dolphin monument", was in the form of a gallows[40] as on the Silin mosaic.[32] The elements depicted on the mosaic are also present on the "iconography of the Circus Maximus", but a gap prevents us from confirming the presence of an obelisk.[47] The building may have included "egg aediculae", which are included in the gap in the mosaic and have been documented on the Silin mosaic, the Lyon mosaic and the remains of the Merida spina.[40]

Around the bollard run four quadrigas, one of which is going in the opposite direction to the others.[48][49] Three quadrigas are going from right to left, and one of them is stopping.[50] The quadriga that has completed the seven laps[49] is the winner: it wears a palm[51] and has the reins around its waist.[38] The charioteers wear a helmet with a crest and the harnessed horses have a plume of feathers.[51]

When the creta, the finishing line on which the referees stood, was crossed, the winner had to make a U-turn to be presented with the palm by a magistrate and prepare to parade in front of the stands;[52] he then had to return to the carceres, to the left of the entrance gate: the charioteer in the mosaic stands back to slow his horses and prepares to ride around the meta secunda.[50] A rider is standing in front of the winning quadriga: this is the jubilator or hortator (or, according to Mohamed Yacoub, the propulsor[38]), whose job it is to encourage the winner.[51]

The quadriga that came second was in the process of stopping, "with its body leaning heavily backwards",[53] and joining the carceres, but had to stop at the invitation of a figure holding an amphora and a whip, a "track official",[54] the morator ludi according to Léopold-Albert Constans or a sparsor according to Mohamed Yacoub[49]: This person stops the quadriga by spraying the axles of the chariot and cares for the equines, giving them water to cool their nostrils. On the opposite side of the track, another morator (or sparsor), partially preserved, stops a quadriga whose driver raises his arm in acceptance of defeat. This is a normal intervention, as "the outcome of the race was already known".[49] The third quadriga appears to be whipping its horses, hoping to win a place.[55]

| Finish rank | Team colour |

|---|---|

| 1st (winner) | Blues |

| 2 | White (by deduction) |

| 3 | Red |

| 4 | Greens |

Interpretation[edit]

Distorted representation of reality[edit]

The "errors, anomalies and oddities" observed in ancient representations of buildings are linked to a problem of interpretation.[1] The mosaic represents reality but in a distorted way, in particular the "cramped aspect of the attic" and without respect for proportions, as was customary in ancient representations.[22] According to observations made during archaeological excavations, the attic was in fact high in reality, despite the partial nature of the excavations.[20] The representation of the carceres is also inaccurate, with a smaller number than in reality: this corresponds to the habit of "reducing the series" often observed.[10] Eight carceres would not have been enough to occupy the entire width of the building.[22] The carceres identified during the excavations were between 5.50 m and 6 m wide and formed an arc of a circle, leaving a space of around 7 m for the porta pompæ.[10] Similarly, the mosaicist represented only a small proportion of the bays in the performance building: only sixteen are shown in the work, a figure that bears no relation to their actual number.[28] In this way, the mosaicist wanted to show only "the essential characteristics "[10] of the building. The bays were also narrower than those depicted.[20]

The rounded shape of the ends of the building may be linked to the primitive state of the performance building, as in Merida,[1] before the carceres were rebuilt in the 2ndL 15 or 4th century.[1] The plan of the building has a curved side and arched carceres on the opposite side.[1]

The mosaicist may have simplified the representation,[27] giving "a simplified image of the circus", omitting the secondary lodge present on African mosaics such as those at Dougga[8] and the triumphal arch usually present on the arena. We therefore have a "deliberate simplification of the image".[17] The simplification may be linked to a technical problem, as the tesserae do not allow all the details to be shown, such as the separations of the metae from the spina, archaeologically attested elsewhere but presented as split on the Carthage mosaic.[13] The number of aediculae present on the spina of the mosaic, after filling in the gaps, seems realistic despite the principle of simplification, with four aediculae present out of a total of five or six in the actual building.[6] The circus must also have contained a large number of statues that are not represented in the mosaic.[41]

The proportions of the circus are not respected, "as is always the case in ancient images".[20] The circus is depicted as being seven times too short or the ring too wide.[32] The mosaicist obeys the rules of ancient representations of "compression in height" or "compression in width".[28] The two aediculae above the cavea are placed on the same side, whereas these buildings faced each other in Rome; to depict them in this way would be to apply the rule of "tilting towards the observer".[28][32] The distortion leaves room for the representation of figures and scenes with chariots, applying a rule of greater representation of living beings than of "inert things".[32]

Despite these elements, the mosaicist's approach is "appropriate and astute" in Fabricia Fauquet's opinion.[28] The result is an "expressive image" in which the deformations serve to express her ideas.[8]

Ancient representations of chariot races for commemorative purposes[edit]

There are many representations of racehorses in the mosaics of present-day Tunisia: the animals are often named, their names being linked to qualities or to the gods.[30]

Representations of the Great Circus can be found in Italy in various media, particularly terracotta, sarcophagi and coins, before being transposed to Africa in mosaics in the first century. The Carthage work is the only one to offer a vision of both the building and the spectacle, the artist's "desire to show everything".[16]

Léopold-Albert Constans considered the dating to be no earlier than the 2nd century, but this is not certain and has been discussed by specialists following this initial study. Domitian increased the number of carceres at the Circus Maximus from eight to twelve, but this change cannot be generalised with certainty.[57] This work is "the oldest representation of a circus scene on a mosaic in Tunisia "[2] known to date,[49] along with the mosaic pavement uncovered at Silin in Tripolitania.[58]

The Carthage mosaic has a commemorative purpose, even though there are no names of horses or charioteers and the quadrigas are depicted in a classical manner: the work is intended to preserve the memory of a magistrate's generosity in putting on a show, similar to other mosaics commemorating amphitheatre games,[54] such as the Magerius mosaic. The competitions held in the circus were very expensive.[4] These competitions included venationes held in amphitheatres and circuses.[30] A necropolis near the building contains a marble statue of a coachman that is kept in the National Museum of Carthage.[47]

Probable representation of a vanished building and an artistic tradition tending towards realism[edit]

The mosaic undoubtedly represents the circus of Carthage[15][59] given the results of archaeological excavations and the study of this type of performance building[20] which allow a coherent interpretation.[41] The circus at Carthage was in fact present before the eyes of the mosaicists.[22][60] Mosaics in the provinces represent local circuses.[6][61]

The circus, built in the mid-1st or late-1st-early-1st century, disappeared completely at the beginning of the 20th century.[5] This building has only been partially excavated and its remains are very poorly preserved.[62] Those uncovered during the excavations date from the Antonine period, although the building was enlarged under the Severans, before being repaired in the Theodosian period.[63] After being abandoned in the fifth century, the building was used as a stone quarry for centuries, and the site was listed as a historic monument on March 1, 1905. The site was partially excavated in the 1980s as part of UNESCO's international campaign.[64] The site remained under threat from "uncontrolled urbanisation" at the beginning of the 21st century.[65]

Studies have shown the building to be the third largest circus in the Roman Empire, after the Circus Maximus and the Circus of Antioch, with a track length of 496 m, a width of 77 m to 78 m and dimensions of 580 m by 129 m.[66][67] It was "the largest circus in Africa "[68] and could accommodate 60,000 to 70,000 spectators according to Samir Aounallah.[69] According to Adeline Pichot, it could hold 40,000 to 45,000 spectators.[70] This type of building was the prerogative of "large, wealthy cities",[4] although many towns had more basic facilities, such as Dougga where the races took place in a field.[59]

The mosaic of the circus of Carthage, like other works that allow us to "confront the image with archaeological reality", has, according to Fabricia Fauquet, "a definite connection with the reality of the buildings".[71] According to Jean-Claude Golvin and Fauquet, we should "put more faith in ancient images" because their information is "credible".[61] The mosaic shows the spina, part of the Carthage circus that has not been excavated.[47] The circus features a statue of Cybele on a lion: in Africa, Cybele is likened to Cælestis,[72] "the goddess par excellence of Roman Africa, heir to the Carthaginian Tanit "[38] according to the interpretatio romana. This work, like the Silin mosaic, is a reminder of the shape of this building. The statue is in the middle of the spina and no fragment of the work shows any trace of an obelisk, an element present elsewhere except in Africa.[30] The number of elements present or restored on the mosaic must have been close to those present on the building itself, five elements having been found at the Maxentian circus and six at Merida.[41] The Carthage circus mosaic is also a unique example, at the time of its discovery, of a representation of a velum in a circus mosaic, according to some specialists[14][16] a thesis that has since been denounced.

This work is also close to an artistic tradition that seeks to "illustrate reality", and is opposed to the Hellenistic art that prevailed until then, according to Mohamed Yacoub,[49] the "cultivated tradition" of the early 2nd century. Representations of the "many aspects of everyday life" were the order of the day[54] and would be widely represented in the mosaic school of Roman Africa.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 286)

- ^ a b Slim & Fauqué (2001, p. 182)

- ^ Ben Abed-Ben Khedher (1992, pp. 62–63)

- ^ a b c Hassine Fantar, Aounallah & Daoulatli (2015, p. 118)

- ^ a b c d Constans (1916, p. 249)

- ^ a b c d Fauquet (2002, p. 429)

- ^ a b c d e Golvin & Fauquet (2003, pp. 285–286)

- ^ a b c d e f Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 287)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 419)

- ^ a b c d e f g Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 285)

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, pp. 285–286)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 421–422)

- ^ a b c d e Fauquet (2002, p. 426)

- ^ a b c d Constans (1916, p. 250)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yacoub (1993, p. 126)

- ^ a b c d e f g Yacoub (1995, p. 303)

- ^ a b c Fauquet (2002, p. 424)

- ^ Ben Abed-Ben Khedher (1992, p. 63)

- ^ a b Golvin (2012, p. 89)

- ^ a b c d e Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 284)

- ^ Golvin (2012, pp. 108–109)

- ^ a b c d Fauquet (2002, p. 420)

- ^ a b Constans (1916, pp. 250–251)

- ^ a b Constans (1916, p. 251)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 419)

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 284)

- ^ a b Fauquet (2002, p. 423)

- ^ a b c d e Fauquet (2002, p. 425)

- ^ Constans (1916, pp. 251–252)

- ^ a b c d Golvin (2012, p. 110)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 425)

- ^ a b c d e f g Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 288)

- ^ Constans (1916, p. 253)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 420)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 422–423)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 423–424)

- ^ Constans (1916, p. 253)

- ^ a b c d e f Yacoub (1995, p. 304)

- ^ Constans (1916, pp. 253–254)

- ^ a b c Fauquet (2002, p. 427)

- ^ a b c d e f g Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 289)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 427–428)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 428–429)

- ^ Constans (1916, p. 254)

- ^ Constans (1916, pp. 254–255)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 426–427)

- ^ a b c Golvin (2012, p. 109)

- ^ Ben Abed-Ben Khedher (1992, p. 62)

- ^ a b c d e f Yacoub (1993, p. 127)

- ^ a b Constans (1916, pp. 255–256)

- ^ a b c Constans (1916, p. 256)

- ^ Slim & Fauqué (2001, p. 182)

- ^ Yacoub (1995, pp. 304–305)

- ^ a b c Yacoub (1995, pp. 305)

- ^ Constans (1916, pp. 257–258)

- ^ Constans (1916, p. 258)

- ^ Constans (1916, pp. 258–259)

- ^ Yacoub (1995, pp. 302)

- ^ a b Golvin (2012, p. 111)

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, pp. 284–285)

- ^ a b Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 290)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 422)

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 283)

- ^ Ennabli (2020, p. 297)

- ^ Ennabli (2020, p. 297)

- ^ Golvin (2012, p. 108)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 417)

- ^ Ennabli (2020, p. 298)

- ^ Aounallah (2020, p. 180)

- ^ Pichot (2005, p. 6)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, pp. 429–430)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 428)

Bibliography[edit]

- Aounallah, Samir (2020). Carthage: archéologie et histoire d'une métropole méditerranéenne, 814 avant J.-C.-1270 après J.-C. Paris: CNRS Éditions. ISBN 978-2-271-13471-4.

- Ben Abed-Ben Khedher, Aïcha (1992). Le musée du Bardo: une visite guidée. Cérès. ISBN 978-9973-700-83-4.

- Dunbabin, Katherine (1978). The Mosaics of Roman North Africa: Studies in Iconography and Patronage. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-813217-2.

- Ennabli, Abdelmajid (2020). Carthage: les travaux et les jours. 978-2-271-13115-7: CNRS Éditions.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Fauquet, Fabricia (2002). Le cirque romain: essai de théorisation de sa forme et de ses fonctions (thèse de doctorat en histoire, langues et littératures anciennes). Université de Bordeaux III.

- Gauckler, Paul (1910). Inventaire des mosaïques de la Gaule et de l'Afrique, vol. II: Afrique proconsulaire (Tunisie). Ernest Leroux.

- Golvin, Jean-Claude; Fauquet, Fabricia (2003). " Les images du cirque de Carthage et son architecture, essai de restitution », dans Jean-Pierre Bost, Jean-Michel Roddaz et Francis Tassaux (dir.), Itinéraire de Saintes à Dougga : mélanges offerts à Louis Maurin, Bordeaux, Ausonius, coll. « Mémoires ". Ausonius. ISBN 2-910023-41-9.

- Golvin, Jean-Claude (2012). Le stade et le cirque antiques: sport et courses de chevaux dans le monde gréco-romain, Lacapelle-Marival. Archéologie Nouvelle. ISBN 978-2-9533973-7-6.

- Hanoune, Roger (1969). " Trois pavements de la Maison de la course de chars à Carthage ". Mélanges de l'École française de Rome.

- Fantar, M'hamed Hassine; Aounallah, Samir; Daoulatli, Abdelaziz (2015). Le Bardo, la grande histoire de la Tunisie: musée, sites et monuments. Alif. ISBN 978-9938-9581-1-9.

- Humphrey, John H. (1986). Roman circuses : Arenas for Chariot Racing, Berkeley. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04921-5.

- Pichot, Adeline (2005). « Jeux et spectacles en Afrique romaine » vol. 11. Chronozones.

- Slim, Hédi; Mahjoubi, Ammar; Belkhodja, Khaled; Ennabli, Abdelmajid (2003). Histoire générale de la Tunisie, vol. I : L'Antiquité. Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-1695-6.

- Slim, Hédi; Fauqué, Nicolas (2001). La Tunisie antique : de Hannibal à saint Augustin, Paris. Mengès. ISBN 978-2-85620-421-4.

- Thuillier, Jean-Paul (1999). " Agitator ou sparsor ? À propos d'une célèbre statue de Carthage ". CRAI.

- Thuillier, Jean-Paul (1999). " Agitator ou sparsor ? À propos d'une célèbre statue de Carthage ". CRAI.

- Yacoub, Mohamed (1993). Le Musée du Bardo: départements antiques, Tunis. Agence nationale du patrimoine. ISBN 978-9973-917-12-6.

- Yacoub, Mohamed (1995). Splendeurs des mosaïques de Tunisie, Tunis. Agence nationale du patrimoine. ISBN 9973-917-23-5.

- Constans, Léopold-Albert (1916). Mosaïque de Carthage représentant les jeux du cirque ». Revue archéologique.

External links[edit]

- Zaher Kammoun, "Des mosaïques de Carthage", on zaherkammoun.com, 8 February 2017.

- Zaher Kammoun, "Les jeux du cirque dans la mosaïque romaine en Tunisie", at zaherkammoun.com, 7 February 2017.