Fort Prince George

| Fort Prince George | |

|---|---|

| Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (present day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) | |

| Coordinates | 40°26′23″N 79°58′35″W / 40.43972°N 79.97639°W |

| Type | Military fort |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1754 |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Captain William Trent Lieutenant John Fraser Ensign Edward Ward |

| Designated | May 8, 1959 |

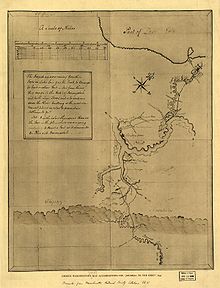

Fort Prince George (sometimes referred to as Trent's Fort) was an incomplete fort on what is now the site of Pittsburgh, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. The plan to occupy the strategic forks was formed by Virginia Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie, on the advice of Major George Washington, whom Dinwiddie had sent on a mission to warn French commanders they were on English territory in late 1753, and who had made a military assessment and a map of the site. The fort was still under construction when it was discovered by the French, who sent troops to capture it. The French then constructed Fort Duquesne on the site.

Background

[edit]In 1749 the British Crown awarded the Ohio Company a grant of 500,000 acres in the Ohio Country between the Monongahela and the Kanawha Rivers, provided that the company would settle 100 families within seven years.[1] The Ohio Company was also required to construct a fort and provide a garrison to protect the settlement at their own expense.[2] The Treaty of Logstown was intended to open up land for settlement so that the Ohio Company could meet the seven-year deadline, and to obtain explicit permission to construct a fort.[3]: 123–144

On 29 May 1751, at a council meeting at Logstown between George Croghan, Andrew Montour and representatives of the Six Nations, Croghan reported the following statement from Iroquois speaker Toanahiso:

- "We expect that you our Brothers will build a Strong House on the River Ohio, that if we should be obliged to engage in a war that we should have a Place to secure our Wives and Children...Now, Brothers, we will take two months to consider and choose out a place fit for that Purpose, and then we will send You word. We hope Brothers that as soon as you receive our Message you will order such a House to be built. Brothers: that you may consider well the necessity of building such a Place of Security to strengthen our arms, and that this, our first request of that kind may have a good effect on your minds.[4]: 538–39 "

Governor Hamilton used this statement as evidence to the Pennsylvania Provincial Council that they should pay for the construction of a fort at a site selected by the sachems at Logstown, arguing that unless the fort were built, the English might lose not only Indian support, but control over the fur trade in Ohio.[5] However, the Provincial Council decided not to provide funding for a fort, arguing that fair dealings and occasional presents would hold the Indians as allies.[4]: 547 At the Treaty of Logstown in June 1752, Tanacharison agreed to the construction of a fort upriver from Logstown, and Virginia's Ohio Company began construction of a road from Will's Creek to the Monongahela River where they built a storehouse at the mouth of Redstone Creek.[6]: 45 At a meeting in Winchester, Virginia in September 1753, Native American leaders expressed willingness to cooperate with the British and repeated their request that a fort be built on the Ohio.[7]: 364 The following summer, the Ohio Company obtained permission from the Six Nations to build Fort Prince George.[6]: 54

Washington's journey

[edit]Governor Dinwiddie decided to warn the French that they were occupying British-claimed land. He assigned the 21-year-old Major George Washington to carry the message to French commander Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre at Fort Le Boeuf. Washington left Williamsburg, Virginia on October 31, 1753. On his way to Logstown to meet with Native American allies, he stopped at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, noting that "I spent some Time in viewing the Rivers, and the Land in the Fork, which I think extremely well situated for a Fort, as it has the absolute Command of both Rivers."[8]: 44 Washington met with the French commander, who refused to acknowledge that the British had any claim over land in the Ohio Country. On January 6 1754, near Will's Creek, while Washington was on his way back to Williamsburg, he met "17 horses loaded with Materials and stores for a fort at the Forks of the Ohio."[8]: 44 These supplies were intended for Fort Prince George.[7]: 365 [6]: 36

Trent's orders

[edit]On January 26, Governor Dinwiddie issued a captain's commission in the Virginia militia to fur trader William Trent,[6]: 44 with orders to raise one hundred men who would "keep possession of his Majesty's land on the Ohio, and waters thereof, and to dislodge and drive away, and...to kill and destroy, or take prisoners, all and every person and persons whatsoever, not subjects of the King of Great Britain, who now are, or shall hereafter come to settle, and take possession of any lands on the said Ohio." A second letter informed Trent that he should proceed to the Ohio River to assist in the building of a fort there and defend it against any French actions. George Washington was ordered to raise an additional one hundred men to garrison the fort.[7]: 366

Construction

[edit]

According to the 1756 deposition of Ensign Edward Ward, on February 17 Trent met Christopher Gist and Seneca leader Tanacharison and his followers, at the Forks of the Ohio.[6]: 54 After clearing the ground, Tanacharison "laid the first log and said that the fort belonged to the English & them and whoever offered to prevent the building of it, they, the Indians, would make war against them."[8]: 46–47 Construction was initiated by 33 Virginia militia, with 8 fur traders and trappers recruited by Trent with the assistance of his friend, Indian trader John Fraser, to whom Trent gave a lieutenant's commission.[7] Trent accepted on condition that he be permitted to remain at his plantation, where he was engaged in fur trading, and come to the fort only once a week or whenever necessary.[9]: 90 Within 10 days they had "finished a Store House, and a large quantity of timber hew'd, boards saw'd, and shingles made."[8]: 47 The fort was referred to as "Trent's Fort," and the title of Fort Prince George, (named for the crown prince and later King George III), was not attached to the fort until September 1754, when Governor Dinwiddie proposed it in a letter to his London superiors.[10][11][12]

Capture

[edit]On March 4 1754, a French detachment under Michel Maray de La Chauvignerie discovered the fort under construction. Chauvignerie immediately reported to Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur at Venango,[13]: 129 [14] that "The scouts...took notice [of] an advanced house almost made, which is to serve as a Magazine, but because of the distance they could not know in what manner they were constructing their fort, since it was still only marked out."[6]: 54 Governor-General Duquesne wrote immediately to Contrecœur: "From the letter from Sieur La Chauvignerie of March 11, it appears that the English are planning to settle at the mouth of [the Allegheny River], since there is already a storehouse built there. You must hasten, Sir, to interrupt and even destroy their work from the start, because their consolidation would lead us to a siege...which it would be wise to avoid, considering the bad state of the finances of the King."[13]: 132

At that point, only a storehouse had been built, as Trent's men were still clearing the land and preparing stakes for the palisade. They had been subsisting on flour and corn they brought with them, along with meat traded to them by Native Americans from Logstown, but their supplies were running low. They were anticipating the arrival of now Lieutenant Colonel Washington and his troops, but on March 17, Trent decided to travel to Wills Creek to obtain more supplies, leaving Ensign Edward Ward in command, as Lieutenant Fraser was at his own plantation at Turtle Creek, tending to personal business.[7]: 367

On April 13, Ensign Ward received word that a French military force was descending the Allegheny and would arrive within days.[6]: 61 Alarmed, he went to inform Lieutenant Fraser, but there was nothing they could do except abandon the fort, in violation of their orders. Fraser refused to return to the fort, leaving Ward to confront the French. Ward returned to the construction site and had his men erect a stockade wall around the storehouse, completing it on April 16.[8]: 49 Ward was determined to "hold out to the last extremity before it should be said that the English had retreated like cowards before the French forces appeared" as that "would give the Indians a very indifferent opinion of the English ever after."[7]: 367 In his deposition of June 30, 1756, Ensign Ward reported that "there was no Fort but a few Palisades he ordered to be cut and put up four days before the French came down."[8]: 52

In April, a force of more than 600 men[Note 1] under the command of Captain Contrecœur traveled in pirogues and batteaux down the Allegheny River from Venango, landing at Shannopin's Town.[15]: 135 [17] On April 18 the French Commander sent Captain Francois Le Mercier, two drummers and an interpreter to present Ensign Ward with a summons stating that the French Army intended to lay siege to the fort, and commanded Ward to "retreat peaceably with your troops" and "not to return." Ward and his men were given one hour to leave. Ward, on advice from Tanacharison, who was present, requested that the French wait until Ward's commanding officer, Captain Trent, returned, but Contrecœur refused. Ward then asked if the British might wait until the following day to leave, and Contrecœur agreed. He then invited Ward to dine with him, and Ward accepted. At dinner, Ward politely refused to discuss military or political matters, and declined Contrecœur's offer to buy Ward's carpentry tools.[6]: 68

According to Ward, "the French entered, but behaved with great civility [and] said it might be their fate ere long to surrender it again so they would set [us] a good example. They however immediately went to work removing some of the logs as they complained the fort was not to their liking, and by break of day next morning 50 men went off with axes to hew logs to enlarge it." Tanacharison "stormed greatly at the French and told them it was he Order'd that Fort and laid the first Log of it himself, but the French paid no Regard to what he said."[8]: 50 The British withdrew, and the French destroyed the partially built fort in order to construct their own.[8]: 51–52

Aftermath

[edit]Captain Trent's men marched to Washington's camp at Wills Creek.[9]: 91 They were mostly Indian traders and Trent's employees, but still considered themselves militia and therefore not under Washington's command. Washington ordered them to wait for the Governor's instructions, but the men ignored this and disbanded.[8]: 51

Tanacharison wrote immediately to Washington, stating that he was "ready to fight them as you are yourselves...if you do not come to our aid soon, it is all over with us, and I think that we shall never be able to meet together again."[18] Washington regarded the capture of Trent's Fort as an act of war, and prepared to advance, writing on April 20 to Governor Dinwiddie to request artillery. Counting on Tanacharison to support him with Native American warriors, he prepared to attack French troops in what would become the first battle of the French and Indian War, the Battle of Jumonville Glen.[7]: 369

On May 1, Governor Dinwiddie, unaware that the fort had been captured, wrote to Governor Horatio Sharpe of Maryland that "The Plan of the Fort is not yet Drawn, as the Ground is not fix'd on being left with discretional Power to the Engineer." When Ensign Ward returned from Williamsburg, he brought letters dated May 4, expressing anger with Trent and Fraser to Colonel Joshua Fry: "I am advis’d that Capt. Trent, and his Lieut., Fraser have been long absent from their duty...Which Conduct & Behaviour I require & expect You will enquire into at a Court Martial, & give Sentence accordingly."[19][8]: 51 Lieutenant Fraser was almost court-martialed at Williamsburg for desertion, but he was released after Washington reminded Governor Dinwiddie that Fraser had accepted his lieutenant's commission with reservations. He later served as Chief of Scouts in General Edward Braddock's army, Adjutant of Virginia Forces, and Captain of guides in the army of Brigadier-General John Forbes.[9]: 92

The French erected Fort Duquesne after seizing Fort Prince George, and maintained control of traffic on the Ohio River until November, 1758. This had a devastating impact on British trade with Native Americans in the Ohio Country, leading many to side with the French at the beginning of the French and Indian War.[20]: 4

Fort Prince George was the first of five forts to be built to control the strategic "Forks of the Ohio".[21] Following the capture of Fort Duquesne in the 1758 Forbes Expedition, the British built Fort Pitt. Mercer's Fort was a temporary British fort built to defend against a French counterattack while Fort Pitt was being constructed. The final fort in what is now downtown Pittsburgh was an American post called Fort Lafayette, built in 1792 and located farther up the Allegheny River.

Memorialization

[edit]A historical marker commemorating Fort Prince George was placed in Point State Park in downtown Pittsburgh on May 8, 1959.[10][22] A diorama depicting the fort's surrender to the French can be seen at the Fort Pitt Museum in Pittsburgh.[23]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sources disagree on the number of men under Contrecœur's command. Ensign Ward testified in 1754 that witnesses later informed him that the French arrived in 360 pirogues and batteaux, each carrying 4 passengers, although 18 of the boats carried light cannon, and he estimated that close to a thousand French troops and Indians were in the force. In 1756 Ward testified that the French were "eleven hundred in number." Trent reported 700 men and 9 cannons.[6]: 61 Dahlinger, after a careful examination of French documents including the diary of one of Contrecœur's soldiers, concludes that the force consisted of "from five to six hundred men."[15]: 135 Other sources also report between 500[16]: 15 and 600[8]: 49 French soldiers, arguing that Ward exaggerated the number to gain sympathy.

References

[edit]- ^ Ambler, Charles Henry. "George Washington and the West". Historic Pittsburgh Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Thurston, George H. (1888). "Allegheny county's hundred years". Historic Pittsburgh General Text Collection. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Kenneth P. Bailey, The Ohio Company of Virginia and the Westward Movement, 1748-1792: A chapter in the History of the Colonial Frontier, University of California at Los Angeles. The Arthur H. Clark Co., Glendale, California, 1939

- ^ a b Samuel Hazard, ed. Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania: From the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government, Mar. 10, 1683-Sept. 27, 1775, Vol 4 of Colonial Records of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Provincial Council, Pennsylvania Committee of Safety; J. Severns, 1851.

- ^ Wainwright, Nicholas B. "An Indian Trade Failure: The Story of the Hockley, Trent and Croghan Company, 1748-1752." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 72, no. 4 (1948): 343-75

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cherry, Jason A. Pittsburgh's Lost Outpost: Captain Trent's Fort. Charleston, SC: HISTORY Press, 2019.ISBN 1467141623

- ^ a b c d e f g Doug MacGregor, "The Shot Not Heard Around the World: Trent's Fort and the Opening of the War for Empire." Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Summer 2007, Vol. 74, No. 3, State College: Penn State University Press pp. 354-373

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hunter, William Albert. Forts on the Pennsylvania Frontier: 1753–1758, (Classic Reprint). Fb&c Limited, 2018; pp 313-19

- ^ a b c Clark, Howard Glenn. "John Fraser, Western Pennsylvania Frontiersman, Parts 1 & 2" Western Pennsylvania History Magazine, Vol. 38, No 3-4, Fall-Winter 1955; pp 83-93

- ^ a b "Fort Prince George," historical marker placed May 8, 1959, explorepahistory.com

- ^ Spencer Tucker, The Encyclopedia of North American Colonial Conflicts to 1775: A-K, ABC-CLIO, 2008

- ^ Stotz, Charles Morse (2005). Outposts Of The War For Empire: The French and English In Western Pennsylvania: Their Armies, Their Forts, Their People 1749-1764. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-4262-3.

- ^ a b PAPIERS CONTRECOEUR Le Conflit Angelo - Francias Sur L' Ohio De 1745 a 1756. English translation of documents in the Quebec Seminary by Donald Kent, 1952

- ^ Henry Wilson Temple, "Logstown," The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, vol. 1, no. 1, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania., 1918. Pp 248-258

- ^ a b Charles W. Dahlinger, "The Marquis Duquesne, Sieur de Menneville, Founder of the City of Pittsburgh," part 2, Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, 15, August 1932

- ^ Schumann, M., Schweizer, K. W. The Seven Years War: A Transatlantic History. London: Routledge; Taylor & Francis, 2012

- ^ "From Benjamin Franklin to Richard Partridge, 8 May 1754," Founders Online, National Archives,The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 5, July 1, 1753, through March 31, 1755, ed. Leonard W. Labaree. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962, pp. 272–275.

- ^ George Washington, "Expedition to the Ohio, 1754: Narrative," Founders Online, National Archives. The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 1, 11 March 1748 – 13 November 1765, ed. Donald Jackson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976, pp. 174–210.

- ^ "To George Washington from Robert Dinwiddie, 4 May 1754," Founders Online, National Archives.The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 1, 7 July 1748 – 14 August 1755, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Charles W. Dahlinger, "Fort Pitt," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, vol 5, No. 1, January 1922; Pittsburgh: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania

- ^ "Fort Prince George, aka Trent’s Fort – February 1754," Society of Colonial Wars of Pennsylvania, 2024

- ^ Fort Prince George historical marker

- ^ Rusty Glessner, "Exploring Point State Park in Pittsburgh"

- French and Indian War forts

- Forts in Pennsylvania

- Colonial forts in Pennsylvania

- British forts in the United States

- History of Pittsburgh

- George Washington

- Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

- Buildings and structures in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

- French military occupations

- Pre-statehood history of Pennsylvania