Fortifications of Heraklion

| Fortifications of Heraklion | |

|---|---|

| Heraklion, Crete, Greece | |

Bethlehem Bastion | |

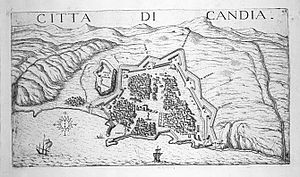

Map of Candia (Heraklion) and its fortifications in 1651 | |

| Coordinates | 35°20′3.3″N 25°7′37.8″E / 35.334250°N 25.127167°E |

| Type | City wall |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Mostly intact |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 9th–10th centuries (Arab and Byzantine walls) 1462–16th century (Venetian walls) |

| Built by | Byzantine Empire Emirate of Crete Republic of Venice |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Candia |

The fortifications of Heraklion are a series of defensive walls and other fortifications which surround the city of Heraklion (formerly Candia) in Crete, Greece. The first city walls were built in the Middle Ages, but they were completely rebuilt by the Republic of Venice.[1] The fortifications managed to withstand the second longest siege in history for 21 years, before the city fell to the Ottomans in 1669.

Heraklion's fortifications have made it one of the best fortified cities in the Mediterranean.[2] The walls remain largely intact to this day, and they are considered to be among the best preserved Venetian fortifications in Europe.[3]

History

[edit]Byzantine and Arab walls

[edit]The first fortifications in what is now Heraklion were built by the Byzantine Empire. The city was captured by Arabs in 824, and it became the capital of the Emirate of Crete. At this point, they built a wall of unbaked bricks around the city, and surrounded it by a ditch. The new capital became known as Rabdh al-Khandaq (Trench Castle).[3]

Meanwhile, the Byzantines tried to recapture Crete from the Arabs because of its strategic importance. After several unsuccessful attempts, Nikephoros II Phokas managed to take the island in 961. The Arab fortifications were razed, and a new fort known as Rokka was constructed instead. Eventually, the settlement grew, and the Byzantines built new walls on the site of the Arab walls.[3]

Some remains of the Byzantine walls still exist near Heraklion's harbour.[3]

Venetian walls

[edit]

In the early 13th century, Candia (modern Heraklion) and the rest of Crete fell under the control of the Republic of Venice. Initially the Byzantine walls remained in use, and they underwent various modifications. Following the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the expanding Ottoman Empire became a major threat for the Venetians. Due to this threat and the discovery of gunpowder, they decided to build new fortifications around Candia. Construction began in 1462, and the walls took over a century to be built. Their construction was based on designs by prominent military architects Michele Sanmicheli and Giulio Savorgnan (it).It has been proposed that their initial layout was based on a circle with a diameter of exactly 1,000 Venetian passi (ca. 1,740 m), defined by the headpoints of the three outer bastions (Sabbionara, Martinengo, St. Andrea).[4]

Over the years, the fortifications were strengthened with the construction of various outworks, while the Rocca al Mare (now known as the Koules Fortress) was built to protect the harbour entrance.[4]

Ottoman rule and recent history

[edit]The fifth Ottoman–Venetian War broke out when the Ottoman Navy arrived off Crete on 23 June 1645. By August, Canea fell to the Ottomans, while the Fortezza of Rethymno fell in 1646. However, the Venetian garrison in Candia managed to hold out for 21 years, and the Siege of Candia remains the second longest siege in history. The city surrendered in 1669, and the Venetians and most of the population were allowed to leave peacefully, sparing the city from being sacked.[5]

After occupying the city, the Ottomans repaired and maintained its fortifications. The bastions were given Turkish names, for example Martinengo Bastion became Giouksek Tabia.[3]

The Ottomans also built a small fort known as Little Koules on the landward side close to the Rocca al Mare. This was demolished in 1936 while the city was being modernized.[4]

The walls were damaged by German aerial bombardment during the Battle of Crete in World War II, but the damage was repaired.[2] After the war, some of the outworks were demolished to make way for modern buildings, and suggestions were also made to demolish the entire city walls.[6] The demolition was never carried out, and the walls remain largely intact, being among the best preserved Venetian fortifications in Europe.[3]

Layout

[edit]

The Venetian fortifications of Heraklion consist of a roughly triangular enceinte. The land front has seven bastions:

- St. Andrew Bastion

- Pantocrator Bastion

- Bethlehem Bastion

- Martinengo Bastion

- Jesus Bastion

- Vitturi Bastion

- Sampionara Bastion

Cavaliers were built on some of the bastions, and the walls had four main gates and three military gates. The entire enceinte was surrounded by a deep ditch and various outworks, including several ravelins, three hornworks and a crownwork. The Fort of St. Demetrius, consisting of a small bastion and two demi-bastions, was built on the hill to the east of the city.[2]

Another enceinte was built along the city's harbour, facing the sea. The harbour entrance was protected by the Koules Fortress (originally known as Rocca al Mare).

Today, only the Koules Fortress remains of the seaward enceinte. The land front is intact, but the outworks and the Fort of St. Demetrius have been destroyed. Two of the four main gates remain intact.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Cosmescu, D. Venetian Renaissance Fortifications in the Mediterranean, McFarland, 2005. ISBN 1476620180.

- ^ a b c Wass, Stephen. "Heraklion". fortified-places.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "The Castle of Candia (Heraklion)". cretanbeaches. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Katsarakis, Antonis (15 July 2024). "Observations on the Layout of the Sixteenth Century Venetian Land Walls of Candia in Crete, or the Thousand Passi Circle Hypothesis". Nexus Network Journal - Architecture and Mathematics (Springer link). Archived from the original on 2015-04-06. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Candia (Iraklion) - page one: the Walls". romeartlover.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2015.

- ^ "Heraklion Walls". Explore Crete. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "The Venetian Walls of Heraklion". candia.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014.

Sources

[edit]- Steriotou, Ioanna (1980). "Αρχές χαράξεων και κατασκευής των οχυρώσεων του 16ου αιώνα και η εφαρμογή τους στις οχυρώσεις του Χάνδακα" [Principles of Design and Construction of 16th-Century Foritifications and their Application in the Fortifications of Candia]. Πεπραγμένα του Δ' Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου, Ηράκλειο, 29 Αυγούστου - 3 Δεκεμβρίου 1976. Τόμος Β′ Βυζαντινοί και μέσοι χρόνοι (in Greek). Athens: University of Crete. pp. 449–475.