Fungi in art

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

- Pre-Columbian mushroom sculptures (c. 1000 BCE – c. 500 CE)

- A glass sculpture (c. 1940) by mycologist William Dillon Weston, depicting the Botrytis cinerea, a phytopathogen

- 'Champi(gn)ons' (2017), a sculpture by artist Vera Meyer made with parasol mushrooms (Macrolepiota procera, metal, shellac, 30 x 20 x 8 cm).

- 'MY-CO SPACE' (2018), a building prototype using the mycelium of Fomes fomentarius.

Fungi are a common theme and working material in art. Fungi appear in nearly all art forms, including literature, paintings, and graphic arts; and more recently, contemporary art, music, photography, comic books, sculptures, video games, dance, cuisine, architecture, fashion, and design. There are some exhibitions dedicated to fungi, as well as an entire museum (the Museo del Hongo in Chile).

Contemporary artists experimenting with fungi often work within the realm of BioArt and may use fungi as materials. Artists may use fungi as allegory, narrative, or props. In addition, artists may also film fungi with time-lapse photography to display fungal life cycles or try more experimental techniques. Artists using fungi may explore themes of transformation, decay, renewal, sustainability, or cycles of matter. They may also work with mycologists, ecologists, designers, or architects in a multidisciplinary way.

Artists may be indirectly influenced by fungi via derived substances (such as alcohol or psilocybin). They may depict the effects of these substances, make art under the influence of these substances, or in some cases, both.

By artistic area

[edit]In Western art, fungi have been historically connoted with negative elements, whereas Asian art and folk art are generally more favorable towards fungi. British mycologist William Delisle Hay, in his 1887 book An Elementary Text-Book of British Fungi,[1][2] describes Western cultures as being mycophobes (exhibiting fear, loathing, or hostility towards mushrooms). In contrast, Asian cultures have been generally described as mycophiles.[3][4]

Since 2020, the annual Fungi Film Festival has recognized movies about fungi in all genres.[5]

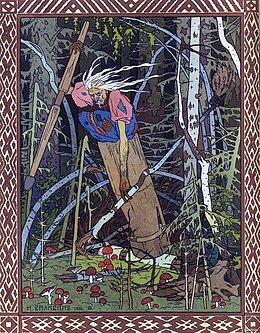

In some stories or artworks, fungi play an allegorical role or is part of mythology and folklore. The visible parts of some fungi – particularly mushrooms with a distinctive appearance (e.g., fly agaric) – have significantly contributed to folklore.[6]

Mushrooms

[edit]

Mushrooms have been represented in art traditions around the world, including western and non-western works of art in ancient and contemporary times.[7] Mayan culture created symbolic mushroom stone sculptures which sometimes include faces that depict in a dreamlike or trance-like expression.[8] Mayan codices also depict mushrooms.[9] Examples of mushroom usage in art from other cultures include the Pegtymel petroglyphs of Russia and Japanese Netsuke figurines.[7]

Contemporary art depictions of mushrooms also exist, such as a contemporary Japanese piece that represents baskets of matsutake mushrooms laid atop bank notes, showing an association between mushrooms and prosperity.[7] Anselm Kiefer's work, Über Deutschland and Sonja Bäumel's Objects use images of mushrooms.[10] Some claim that themes such as sustainable living, and considerations associated with the science of fungi and biotechnologies are present in these works.[10]

Mushrooms have appeared in Christian paintings, as in the panel painting by Hieronymus Bosch, The Haywain Triptych.[11][12] The Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art is maintained by the North American Mycological Association. The stated goal of the registry is "to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between mushrooms and people as reflected in works of art from different historical periods, and to provide enjoyment to anyone interested in the subject."[13] Started by Moselio Schaechter, author of In the Company of Mushrooms, the project is ongoing.[14]

Mycelia or hyphae

[edit]Mycelia and hyphae have seldom been represented, showcased, transformed, or utilized in the traditional arts due to their invisibility and the general overlook. Depictions of mycelia and hyphae in the graphic arts are very rare. The mycelium of certain fungi, like those of the polypore fungus Fomes fomentarius which is sometimes referred to as Amadou, has been reported throughout history as a biomaterial.[15] More recently, hyphae and mycelia have been used as working matter and transformed into contemporary artworks, or used as biomaterial for objects, textiles and constructions. Mycelium is investigated in cuisine as innovative food or as a source of meat alternatives like mycoproteins.[16] The filamentous, prolific, and fast growth of hyphae and mycelia (like molds) in suitable conditions and growth media often makes these fungal forms good subjects of time-lapse photography. Indirectly, psychoactive substances present in certain fungi have inspired works of art, like in the triptych by Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, with curious and visionary imagery inspired, according to some interpretations, by ergot poisoning caused by the sclerotia (hardened mycelium) of the phytopathogenic fungus Claviceps purpurea.[17]

Graphic arts

[edit]

The German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470–1528) depicted a subject suffering from ergotism in The Temptation of St. Anthony (1512–1516), also referred to as St. Anthony's Fire.[citation needed]

Music

[edit]The luthier Rachel Rosenkrantz experiments with fungi (mycelium) to create "mycocast", a guitar body made of fungal biomass because of the acoustic properties of mycelium and its growth plasticity (i.e., the ability to take virtually any shape upon being cast in a desired form).[18] According to an interpretation, violins from wood infiltrated by mycelia of the fungus Xylaria polymorpha (commonly called 'dead man's fingers') produce sounds close to those from a Stradivarius violin.[6] Researchers are investigating the use of the species Physisporinus vitreus and Xylaria longipes in controlled wood decay experiments to create wood with superior qualities for musical instruments.[19][20][21] In some cases, music generation using fungi is conceptual, as in Psychotropic house (2015) and Mycomorph lab (2016) of the Zooetic Pavillion by the Urbonas Studio based in Vilnius (Lithuania) and Cambridge (Massachusetts), in which a mycelial structure is designed to act as an amplifier for sounds from nature mixed into loops.[22][23]

Architecture, sculptures, and mycelium-based biomaterials

[edit]Direct applications of fungi in architecture often start with artistic experimentations with fungi.[24][25][26] Mycelium is being investigated and developed by researchers and companies into a sustainable packaging solution as an alternative to polystyrene.[27]

Early experimentations by artists with mycelia have been exhibited at the New York Museum of Modern Art.[28] Experimentations with fungi as components– and not only as contaminants or degraders of buildings – started around 1950.[29] Use of fungi from the genera Ganoderma, Fomes, Trametes, Pycnoporus, or Perenniporia (and more) in architecture include applications such as concrete replacement, 3D printing, soundproof elements, insulation, biofiltration, and self-sustaining, self-repairing structures.[30][31][32][33]

Besides the study of fungi for their beneficial application in architecture, risk assessments investigate the potential risk fungi can pose with regard to human and environmental health, including pathogenicity, mycotoxin production, insect attraction through volatile compounds, or invasiveness.[34]

Fashion, design, and mycelium-based textiles

[edit]

Historically, ritual masks made of lingzhi (species from the genera Ganoderma) have been reported in Nepal and indigenous cultures in British Columbia.[36] Fungal mycelia are molded or grown into sculptures and bio-based materials for product design, including into everyday objects to raise awareness about circular economics and the impact that petrol-based plastics have on the environment.[37][38] Biotechnology companies like Ecovative Design, MycoWorks, and others are developing mycelium-based materials that can be used in the textile industry. Fashion brands like Adidas, Stella McCartney, and Hermès are introducing vegan alternatives to leather made from mycelium.[39][40][41][42][43][35]

The tinder polypore Fomes fomentarius (materials derived from which are referred to as 'Amadou') has been used by ancestral cultures and civilizations due to its flammable, fibrous, and insect-repellent properties.[6] Amadou was a precious resource to ancient people, allowing them to start a fire by catching sparks from flint struck against iron pyrites. Bits of fungus preserved in peat have been discovered at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr in the UK, modified presumably for this purpose. [44] Remarkable evidence for its utility is provided by the discovery of the 5,000-year-old remains of "Ötzi the Iceman", who carried it on a cross-alpine excursion before his death and subsequent ice-entombment.[45] Amadou has great water-absorbing abilities. It is used in fly fishing for drying out dry flies that have become wet.[46][47] Another use is for forming a felt-like fabric used in the making of hats and other items.[48][49] It can be used as a kind of artificial leather.[50] Mycologist Paul Stamets famously wears a hat made of amadou.[51] Fungi have been used a biomaterial since many centuries, for example as fungus-based textiles. An early example of such "mycotextiles" comes from the early 20th century: a wall pocket originating from the Tlingit, an Indigenous Population from the Pacific Northwest (US) and displayed as historical artefact at the Dartmouth College's Hood Museum of Art, turned out to be made of mycelium from the tree-decaying agarikon fungus.[52] Fungal mycelia are used as leather-like material (also known as pleather, artificial leather, or synthetic leather), including for high-end fashion design products.[53]

Beside their use in clothing, fungus-based biomaterials are used in packaging and construction.[54] There are several advantages and potentials of using fungus-based materials rather than commonly used ones. These include the smaller environmental impact compared with the use of animal products; vertical farming, able to decrease land use; the thread-like growth of mycelium, able to be molded into desirable shapes; use of growth substrate derived from agricultural wastes and the recycling of mycelium within the principles of circular economy; and mycelium as self-repairing structures.[55][56][57]

Culinary arts

[edit]Mushrooms are traditionally the main form of fungi used for direct consumption in the culinary arts. The fermentative abilities of mold and yeasts have a direct influence on a great variety of food products, including beer, wine, sake, kombucha, coffee, soy sauce, tofu, cheese, and chocolate.[58] Recently, mycelium has been increasingly investigated as an innovative food source. The restaurant The Alchemist in Copenhagen, Denmark, experiments with mycelium of fungi such as Aspergillus oryzae, Pletorus (oyster mushroom), and Brettanomyces to create novel fungus-based dishes, including the creation of mycelium-based seafood and the consumption of raw, fresh mycelium grown on a Petri dish with a nutrient-rich broth.[59] The US-based company Ecovative Design is creating fungus-based food as a meat alternative, including mycelium-based bacon.[60][61] The US-based company Nature's Fynd is developing various kinds of food products, including meatless patties and cream cheese substitutes, using the Fy protein from Fusarium.[62]

Contemporary arts

[edit]"At this point, I stepped back and let the sculpture sculpt itself."

— Xiaojing Yan, Mythical Mushrooms: Hybrid Perspectives on Transcendental Matters

Hypha and mycelium get attention as working matter in contemporary art due to their growth and plasticity, and are used to explore the biological properties of degradation, decomposition, budding ('mushrooming'), and sporulation. An early form of BioArt is agar art, where various microorganisms (including fungi) are grown on agar plates into desired shapes and colours. In agar art, fungi and other microorganisms (mostly bacteria) assume different appearances based on intrinsic characteristics of the fungus (species, morphology, fungal form, pigmentation), as well as external parameters (like inoculation technique, incubation time or temperature, nutrient growth medium, etc.). Microorganisms can also be engineered to produce colours or effects which are not intrinsic to them or are not present in nature (e.g., they are mutant from the wild type), like bioluminescence. The American Society for Microbiology (ASM) holds an annual Agar Art Contest which attracts considerable attention and elaborate agar artworks.[63][64] An early agar artist was physician, bacteriologist, and Nobel Prize winner Alexander Fleming (1881–1955).[65][66]

The Folk Stone Power Plant (2017), like the Mushroom Power Plant (2019), by Lithuanian artist duo Urbonas Studio, are physical installations based on mycoglomerates: interpretations and representations of vaguely-described microbial symbioses aimed at energy production alternative to fossil fuel.[67][68] The Folk Stone Power Plant is a "semi-fictional" alternative battery installed in Folkestone, Kent, England, during the Folkestone Triennale, aiming at a reflection about symbioses (both in nature and between artists and scientists) and about unconventional power sources. The design is based on drawings from polymath and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), while the microbial power source, hidden within the stone, mirrors the contribution of mycelial networks (that is, mycorrhiza) in ecology.[67]

In Chinese-Canadian artist Xiaojing Yan's work, Linghzi Girl (2020), female bust statues cast with the mycelium of lingzhi fungus (Ganoderma lingzhi) are exhibited and left to germinate. From the mycelium-based sculptures sprout mushrooms which eventually spread; once ripe, a cocoa-powder dust of spores blooms on the bust, after which the sculptures are preserved by desiccation to stop the fungal cycle and maintain the artwork.[70] Yan thus explains the audience's reaction to her work:

- "The uncanny appearance of these busts seems frightening for many viewers. But a Chinese viewer would recognize the lingzhi and immediately become delighted by the discovery."[36]

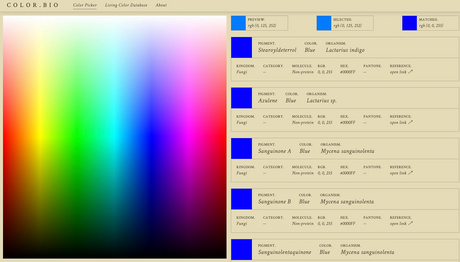

During an artist-in-residence project The colors of life (2021) at the Techische Universität Berlin (Germany), artist Sunanda Sharma focuses on the fungus Aspergillus niger, and visualizes its black pigmentation through fungal melanin by means of video, photography, animation, and time-lapse footage. Within the same residence, the artist created an open-source database The Living Color Database (LCDB), which is an online compendium of biological colors for scientists, artists, and designers. The database links organisms across the tree of life (in particular fungi, bacteria, and archaea) with their natural pigments, the molecules' chemistry, biosynthesis, and colour index data (HEX, RGB, and Pantone), and the corresponding scientific literature. The LCDB comprises 445 entries from 110 unique pigments and 380 microbial species.[69]

Spores

[edit]Single fungal spores are invisible to the naked eye and examples of artworks involving spores are rarer than artworks involving other fungal forms. Fungal spores are employed as an agent of contamination, invasion, infection or decay in works of fiction. In contemporary art, spores might be used to reflect on the process of transformation.[36]

Graphic arts

[edit]Spore prints are created by pressing the underside of a mushroom to a flat surface, either white or colored, to allow the spores to be imprinted on the sheet. Since some mushrooms can be recognized based on the color of their spores, spore prints are a diagnostic tool as well as an illustrative technique.[6] Several artists used and modified the technique of spore printing for artistic purposes. Mycologist Sam Ristich exhibited several of his spore prints in an art gallery in Maine around 2005–2008.[6] The North American Mycological Association created a how-to guide for people interested in creating their own spore prints.[71]

The artwork Auspicious Omen – Lingzhi Spore Painting by Yan creates abstract compositions resembling traditional Chinese landscapes by fixing spores of the linghzi fungus with acrylic reagents.[70] The linghzi mycelial sculptures by Yan, including Linghzi Girl (2020) and Far From Where You Divined (2017) are allowed to germinate into mushrooms during exhibition, creating a dust of spores raining down on the female busts, children, deer, and rabbits. The artworks are then desiccated for preservation, stopping the fungal growth and the metamorphosis of the sculptures. Artworks as such, including growth of the fungus, an incontrollable transformation of the art object, and several forms in the fungal life cycle, are rare.[36]

Comic books and video games

[edit]The video game franchise The Last of Us is a post-apocalyptic, third-person action-adventure game set in North America in the near future after a mutant fungus decimates humanity. The "fungal apocalypse" is inspired by the effect ant-pathogenic fungi like Ophiocordyceps unilateralis have on their insect prey. The infected zombie-like creatures develop cannibalism after inhaling spores and can transmit the fungal infection to other humans by biting. A television adaptation aired in January 2023. "Come into My Cellar" by Ray Bradbury has been adapted into a comic strip by Dave Gibbon and an adaptation into Italian appeared for the comic series Corto Maltese in 1992 with the name "Vieni nella mia cantina".[72]

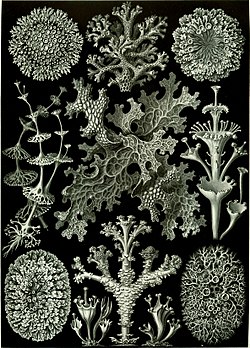

Yeasts, moulds and lichens

[edit]

Contemporary bioartist Anna Dumitriu cultured and showcased fermentation flasks of Pichia pastoris used for the bioconversion of carbon dioxide into biodegradable plastics. The artwork The Bioarchaeology of Yeast recreates biodeterioration marks left by certain yeasts, like black yeast, on work of art and sculptures, and displays them as aesthetic objects, reflecting on the process of erosion.[73]

Contemporary photographer and video artist Sam Taylor-Johnson's time-lapse video, Still Life, documents a platter of fruit in the process of decomposition by mold, representing the natural process of decay.[74]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hay, William Delisle (1887). An Elementary Text-Book of British Fungi. London, S. Sonnenschein, Lowrey. pp. 6–7.

- ^ Arora, David (1986). Mushrooms demystified: a comprehensive guide to the fleshy fungi (2nd ed.). Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-89815-170-8. OCLC 13702933.

- ^ "Mycophile". The New Yorker. 11 May 1957. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Gordon Wasson, Robert; Pavlovna Wasson, Valentina (1957). Mushrooms, Russia, and History. New York: Pantheon Books.

- ^ "Fungi Film Fest (FFF)". Fungi Film Fest. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Millman, Lawrence (2019). Fungipedia: a brief compendium of mushroom lore. Amy Jean Porter. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-19538-4. OCLC 1103605862.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Yamin-Pasternak, Sveta (2011-07-07), "Ethnomycology: Fungi and Mushrooms in Cultural Entanglements", Ethnobiology, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 213–230, doi:10.1002/9781118015872.ch13, ISBN 978-1-118-01587-2

- ^ Lowy, B. (September 1971). "New Records of Mushroom Stones from Guatemala". Mycologia. 63 (5): 983–993. doi:10.2307/3757901. ISSN 0027-5514. JSTOR 3757901. PMID 5165831.

- ^ Lowy, Bernard (July 1972). "Mushroom Symbolism in Maya Codices". Mycologia. 64 (4): 816–821. doi:10.2307/3757936. ISSN 0027-5514. JSTOR 3757936.

- ^ a b Nai, Corrado; Meyer, Vera (2016-11-29). "The beauty and the morbid: fungi as source of inspiration in contemporary art". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 3 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s40694-016-0028-4. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 5611638. PMID 28955469.

- ^ Lawrence, Sandra (2022). The magic of mushrooms : fungi in folklore, superstition and traditional medicine. Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. London. ISBN 978-1-78739-906-8. OCLC 1328029699.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Michelot, Didier; Melendez-Howell, Leda Maria (February 2003). "Amanita muscaria: chemistry, biology, toxicology, and ethnomycology". Mycological Research. 107 (2): 131–146. doi:10.1017/s0953756203007305. ISSN 0953-7562. PMID 12747324.

- ^ "Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art: Introduction". North American Mycological Association. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ "Registry of Mushrooms in Works of Art: Contributors". North American Mycological Association. Retrieved 2022-04-08.

- ^ Cotter, Tradd (2014). Organic mushroom farming and mycoremediation : simple to advanced and experimental techniques for indoor and outdoor cultivation. White River Junction, Vermont. ISBN 978-1-60358-455-5. OCLC 877851800.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Go fish: Danish scientists work on fungi-based seafood substitute". The Guardian. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ Vander Kooi, Carl (February 2012). "Hieronymus Bosch and ergotism" (PDF). WMJ. 111 (1).

- ^ "Meet the Luthier Growing Guitars with Mycelium". Ecovative. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Schwarze, Francis W. M. R.; Spycher, Melanie; Fink, Siegfried (2008). "Superior wood for violins--wood decay fungi as a substitute for cold climate". The New Phytologist. 179 (4): 1095–1104. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02524.x. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 18554266.

- ^ Schwarze, Francis W. M. R.; Morris, Hugh (May 2020). "Banishing the myths and dogmas surrounding the biotech Stradivarius". Plants, People, Planet. 2 (3): 237–243. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10097. ISSN 2572-2611. S2CID 218824236.

- ^ Simpson, Connor (8 September 2012). "How One Man Is Using Fungus to Change the Violin Industry". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "32nd Bienal de São Paulo (2016) - Catalogue by Bienal São Paulo - Issuu". issuu.com. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Lacey, Sharon (2018-04-24). ""Humanities through material engagement": Gediminas Urbonas on artistic research". Arts at MIT. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Mind the Fungi. Vera Meyer, Regine Rapp, Technische Universität Berlin Universitätsbibliothek. Berlin. 2020. ISBN 978-3-7983-3168-6. OCLC 1229035875.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Engage with fungi. Vera Meyer, Sven, ca. Jh Pfeiffer. Berlin. 2022. ISBN 978-3-98781-000-8. OCLC 1347218344.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Meyer, Vera (26 April 2019). "Merging science and art through fungi". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 6 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s40694-019-0068-7. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 6485050. PMID 31057802.

- ^ Abhijith, R.; Ashok, Anagha; Rejeesh, C. R. (1 January 2018). "Sustainable packaging applications from mycelium to substitute polystyrene: a review". Materials Today: Proceedings. Second International Conference on Materials Science (ICMS2017) during 16 – 18 February 2017. 5 (1, Part 2): 2139–2145. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.211. ISSN 2214-7853.

- ^ "Mycotecture (Phil Ross)". Design and Violence. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Stange, Stephanie; Wagenführ, André (18 March 2022). "70 years of wood modification with fungi". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00136-9. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8931968. PMID 35303960.

- ^ Almpani-Lekka, Dimitra; Pfeiffer, Sven; Schmidts, Christian; Seo, Seung-il (2021-11-19). "A review on architecture with fungal biomaterials: the desired and the feasible". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 8 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00124-5. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8603577. PMID 34798908.

- ^ Tavares, Frank (10 January 2020). "Could Future Homes on the Moon and Mars Be Made of Fungi?". NASA. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Paganini, Romano (24 May 2016). "Der Pilz, aus dem die Mauern sind". Beobachter (in Swiss High German). Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Bayer, Eben. "The Mycelium Revolution Is upon Us". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ van den Brandhof, Jeroen G.; Wösten, Han A. B. (24 February 2022). "Risk assessment of fungal materials". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00134-x. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8876125. PMID 35209958.

- ^ a b Vandelook, Simon; Elsacker, Elise; Van Wylick, Aurélie; De Laet, Lars; Peeters, Eveline (2021-12-20). "Current state and future prospects of pure mycelium materials". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 8 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00128-1. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8691024. PMID 34930476.

- ^ a b c d Yan, Xiaojing (20 October 2022). "Mythical Mushrooms: Hybrid Perspectives on Transcendental Matters". Leonardo. 56 (4): 367–373. doi:10.1162/leon_a_02319. ISSN 0024-094X. S2CID 253074757.

- ^ "A fungal future". www.micropia.nl. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ "dae.wiki". www.designacademy.nl. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- ^ Gamillo, Elizabeth. "This Mushroom-Based Leather Could Be the Next Sustainable Fashion Material". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ Haines, Anna. "Fungi Fashion Is Booming As Adidas Launches New Mushroom Leather Shoe". Forbes. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ "Stella McCartney to debut first-ever mushroom leather bag". Vogue Business. 2022-05-23. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ Rosen, Ellen (2022-12-14). "Are Mushrooms the Future of Alternative Leather?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ "It's this season's mush-have Hermès bag. And it's made from fungus". The Guardian. 2021-06-12. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ Robson, H. K. 2018. The Star Carr Fungi. In: Milner, N., Conneller, C. and Taylor, B. (eds.) Star Carr Volume 2: Studies in Technology, Subsistence and Environment, pp. 437–445. York: White Rose University Press. doi:10.22599/book2.q. Licence: CC BY-NC 4.0

- ^ Cotter T. (2015). Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation: Simple to Advanced and Experimental Techniques for Indoor and Outdoor Cultivation. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-60358-456-2.

- ^ John Van Vliet (1999). Fly Fishing Equipment & Skills. Creative Publishing. ISBN 978-0-86573-100-4.

- ^ Jon Beer (October 13, 2001). "Reel life: fomes fomentarius". The Telegraph.

- ^ Greenberg J. (2014). Rivers of Sand: Fly Fishing Michigan and the Great Lakes Region. Lyons Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4930-0783-7.

- ^ Pegler D. (2001). "Useful fungi of the world: Amadou and Chaga". Mycologist. 15 (4): 153–154. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(01)80004-5.

In Germany, this soft, pliable 'felt' has been harvested for many years for a secondary function, namely in the manufacture of hats, dress adornments and purses.

- ^ Alice Klein (Jun 16, 2018). "Vegan-friendly fashion is actually bad for the environment". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022.

- ^ Joe Rogan Experience #1035 - Paul Stamets on YouTube

- ^ Cypress Hansen, Century-Old Textiles Woven from Fascinating Fungus, Scientific American, June 2021.

- ^ Matthew Kronsberg, Leather May Be Most Viable Vegan Alternative to Cowhide, Bloomberg, July 2022.

- ^ Meyer, V (2022). "Connecting materials sciences with fungal biology: a sea of possibilities". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s40694-022-00137-8. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8889637. PMID 35232493.

- ^ Federica Maccotta, Le case del futuro? Saranno fatte di funghi, Wired Italy, August 2022.

- ^ Eben Bayer, The Mycelium Revolution Is upon Us, Scientific American, July 2019.

- ^ Frank Tavares, Could Future Homes on the Moon and Mars Be Made of Fungi?, nasa.gov, Jan 2020.

- ^ Furci, Giuliana (11 November 2021). "The earth's secret miracle worker is not a plant or an animal. It's fungi | Giuliana Furci". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-12-22.

- ^ "Go fish: Danish scientists work on fungi-based seafood substitute". The Guardian. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Feldman, Amy. "Bioengineered Bacon? The Entrepreneur Behind Mushroom-Root Packaging Says His Test Version Is Tasty". Forbes. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Sorvino, Chloe. "Maker Of Mushroom-Sourced Bacon Raises $40 Million To Reach Grocers At Scale". Forbes. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "Fungus Born of Yellowstone Hot Spring Makes Menu at Le Bernardin". Bloomberg.com. 19 July 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ "ASM Agar Art Contest | Overview". ASM.org. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ "This gorgeous art was made with a surprising substance: live bacteria". Science. 2019-11-20. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ "Painting With Penicillin: Alexander Fleming's Germ Art". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Alexander Fleming « Microbial Art". www.microbialart.com. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b Watlington, Emily (29 December 2021). "Mushrooms as Metaphors". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Urbonas Studio's 'Mushroom Power Plant' at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm – Art, Culture, and Technology (ACT)". Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b Sharma, Sunanda; Meyer, Vera (10 January 2022). "The colors of life: an interdisciplinary artist-in-residence project to research fungal pigments as a gateway to empathy and understanding of microbial life". Fungal Biology and Biotechnology. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00130-7. ISSN 2054-3085. PMC 8744264. PMID 35012670.

- ^ a b Watlington, Emily (29 December 2021). "Mushrooms as Metaphors". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "How to: Spore Prints - North American Mycological Association". namyco.org. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ "Vieni nella mia cantina, breve racconto di Ray Bradbury adattato a fumetti da Dave Gibbons". www.slumberland.it. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Dumitriu, Anna; May, Alex; Ata, Özge; Mattanovich, Diethard (5 August 2021). "Fermenting Futures: an artistic view on yeast biotechnology". FEMS Yeast Research. 21 (5): foab042. doi:10.1093/femsyr/foab042. ISSN 1567-1364. PMID 34289062.

- ^ Goldstein, Meredith (17 March 2023). ""Still Life" video proves fruitful for the MFA". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Chan, Jonathan (2020-01-18). "The magic of mushrooms in arts – in pictures". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "'Everyone loves a mushroom': London show celebrates art of the fungi". The Guardian. 25 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- Guy, Nathaniel (2023). Kinoko: A Window into the Mystical World of Japanese Mushrooms. Self-published. ASIN B0BRN8G8KY.