Gareth Jones (journalist)

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 August 1905 |

| Died | 12 August 1935 (aged 29) Inner Mongolia,[1] China |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Gareth Richard Vaughan Jones (13 August 1905 – 12 August 1935) was a Welsh journalist who in March 1933 first reported in the Western world, without equivocation and under his own name, the existence of the Soviet famine of 1930–1933, including the Holodomor and the Asharshylyk[2].[a]

Jones had reported anonymously in The Times in 1931 on starvation in Soviet Ukraine and Southern Russia,[4] and, after his third visit to the Soviet Union, issued a press release under his own name in Berlin on 29 March 1933 describing the widespread famine in detail.[5] Reports by Malcolm Muggeridge, writing in 1933 as an anonymous correspondent, appeared contemporaneously in the Manchester Guardian;[6] his first anonymous article specifying famine in the Soviet Union was published on 25 March 1933.[7]

After being banned from re-entering the Soviet Union, Jones was kidnapped by Chinese bandits and murdered in 1935 while investigating in Japanese-occupied Inner Mongolia; his murder is suspected by some, albeit without any evidence, to have been committed by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD.[8] Upon his death, former British prime minister David Lloyd George said, "He had a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk. … Nothing escaped his observation, and he allowed no obstacle to turn from his course when he thought that there was some fact, which he could obtain. He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered."[9]

Early life and education

[edit]Born in Barry, Glamorgan, Jones attended Barry County School, where his father, Major Edgar Jones, was headmaster until around 1933.[10] His mother, Annie Gwen Jones, had worked in Russia as a tutor to the children of Arthur Hughes, son of Welsh steel industrialist John Hughes, who founded the town of Hughesovka (modern-day Donetsk) in today's eastern Ukraine.[11][12]

Jones graduated from the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth in 1926 with a first-class honours degree in French. He also studied at the University of Strasbourg[10] and at Trinity College, Cambridge, from which he graduated in 1929 with another first in French, German, and Russian.[13] After his death, one of his tutors, Hugh Fraser Stewart, wrote in The Times that Jones had been an "extraordinary linguist".[14] At Cambridge he was active in the Cambridge University League of Nations Union, serving as its assistant secretary.[10]

Career

[edit]Teaching; adviser to Lloyd George

[edit]After graduating, Jones taught languages briefly at Cambridge, and then in January 1930[4] was hired as Foreign Affairs Adviser to the British MP and former prime minister David Lloyd George, thanks to an introduction by Thomas Jones.[10][11][15][16] The post involved preparing notes and briefings Lloyd George could use in debates, articles, and speeches, and also included some travel abroad.[4]

Journalism

[edit]In 1929, Jones became a professional freelance reporter,[17][18][4] and by 1930 was submitting articles to a variety of newspapers and journals.[18]

Germany

[edit]In late January and some of February 1933, Jones was in Germany covering the accession to power of the Nazi Party, and was in Leipzig on the day Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor. Some three weeks later on 23 February in the Richthofen, "the fastest and most powerful three-motored aeroplane in Germany", Jones, along with Sefton Delmer, became the first foreign journalists, after he became Chancellor, to fly with Hitler. They accompanied Hitler and Joseph Goebbels to Frankfurt where Jones reported for the Western Mail on the new Chancellor's tumultuous acclamation in that city.[11][19] He wrote in the Welsh Western Mail that if the Richthofen had crashed the history of Europe would be changed.[19][11]

Soviet Union

[edit]

By 1932, Jones had been to the Soviet Union twice, for three weeks in the summer of 1930 and for a month in the summer of 1931.[4] He had reported the findings of each trip in his published journalism,[18][20][21][4] including three articles titled "The Two Russias" he published anonymously in The Times in 1930, and three increasingly explicit articles, also anonymous, titled "The Real Russia" in The Times in October 1931 which reported the starvation of peasants in Soviet Ukraine and Southern Russia.[4]

In March 1933, he visited the Soviet Union for a third and final time and on 10 March was able to travel to the Ukrainian SSR,[22] due to an invitation from Oscar Ehrt, Vice Consul at the German Consulate in Kharkov.[23] The Vice Consul's son, Adolf Ehrt, was a leading Nazi propagandist who became head of Goebbels’ Anti-Komintern agency.[24] Jones got off the train 40 miles before his declared destination and walked across the border from the Russian SFSR. As he walked he kept diaries of the man-made starvation he witnessed.[25][5] On his return to Berlin on 29 March, he issued his press release, which was published by many newspapers, including The Manchester Guardian and the New York Evening Post:

I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms. Everywhere was the cry, 'There is no bread. We are dying'. This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus, and Central Asia. I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.

In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine. I flung a crust of bread which I had been eating from my own supply into a spittoon. A peasant fellow-passenger fished it out and ravenously ate it. I threw an orange peel into the spittoon and the peasant again grabbed it and devoured it. The Communist subsided. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be two hundred oxen and where there now are six. The peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month's supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night, as there were too many 'starving' desperate men.

'We are waiting for death' was my welcome, but see, we still, have our cattle fodder. Go farther south. There they have nothing. Many houses are empty of people already dead,' they cried.[26][27]

This report was denounced by Moscow-resident British journalist Walter Duranty, who had been obscuring the truth in order to please the dictatorial Soviet regime.[5] On 31 March, The New York Times published a denial of Jones's statement by Duranty under the headline "Russians Hungry, But Not Starving". Duranty called Jones's report "a big scare story".[28][29][7]

Historian Timothy Snyder has written that "Duranty's claim that there was 'no actual starvation' but only 'widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition' echoed Soviet usages and pushed euphemism into mendacity. This was an Orwellian distinction; and indeed George Orwell himself regarded the Ukrainian famine of 1933 as a central example of a black truth that artists of language had covered with bright colors."[30]

In Duranty's article, Kremlin sources denied the existence of a famine; part of The New York Times' headline was: "Russian and Foreign Observers in Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster."[28]

On 11 April 1933, Jones published a detailed analysis of the famine in the Financial News, pointing out its main causes: forced collectivization of private farms, removal of 6–7 millions of "best workers" (the Kulaks) from their land, forced requisitions of grain and farm animals and increased "export of foodstuffs" from USSR.[31]

What are the causes of the famine? The main reason for the catastrophe in Russian agriculture is the Soviet policy of collectivisation. The prophecy of Paul Scheffer in 1929–30 that collectivisation of agriculture would be the nemesis of Communism has come absolutely true.

— Gareth Jones, Balance Sheet of the Five Year Plan, Financial News, 11 April 1933

On 13 May, The New York Times published a strong rebuttal of Duranty from Jones, who stood by his report:

My first evidence was gathered from foreign observers. Since Mr. Duranty introduces consuls into the discussion, a thing I am loath to do, for they are official representatives of their countries and should not be quoted, may I say that I discussed the Russian situation with between twenty and thirty consuls and diplomatic representatives of various nations and that their evidence supported my point of view. But they are not allowed to express their views in the press, and therefore remain silent.

Journalists, on the other hand, are allowed to write, but the censorship has turned them into masters of euphemism and understatement. Hence they give "famine" the polite name of 'food shortage' and 'starving to death' is softened down to read as 'widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition'. Consuls are not so reticent in private conversation.[32]

In a personal letter from Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov (whom Jones had interviewed while in Moscow) to Lloyd George, Jones was informed that he was banned from ever visiting the Soviet Union again. After his Ukraine articles, the only work Jones could get was in Cardiff on the Western Mail covering "arts, crafts and coracles", according to his great-nephew Nigel Linsan Colley.[33] But he managed to get an interview with the owner of nearby St Donat's Castle, the American press magnate William Randolph Hearst. Hearst published Jones's account of what had happened in Ukraine – as he did for the almost identical eye-witness testimony of the disillusioned American Communist Fred Beal[34][35] – and arranged a lecture and broadcast tour of the USA.[33][36]

Japan and China

[edit]Banned from the Soviet Union, Jones turned his attention to the Far East and in late 1934 he left Britain on a "Round-the-World Fact-Finding Tour". He spent about six weeks in Japan, interviewing important generals and politicians, and he eventually reached Beijing. From here he travelled to Inner Mongolia where he secured an interview with Inner Mongolian independence leader Demchugdongrub (Prince De). He continued his journey to Dolonor close to the border of Japanese-occupied Manchukuo in the company of a German journalist, Herbert Müller. Detained by Japanese forces there, the pair were told that there were three routes back to the Chinese town of Kalgan, only one of which was safe.[8]

Kidnapping and death

[edit]Jones and Müller were subsequently captured by bandits who demanded a ransom of 200 Mauser firearms and 100,000 Chinese dollars (according to The Times, equivalent to about £8,000).[37] Müller was released after two days to arrange for the ransom to be paid. On 1 August, Jones's father received a telegram: "Well treated. Expect release soon."[38] On 5 August, The Times reported that the kidnappers had moved Jones to an area 10 miles (16 kilometres) southeast of Kuyuan and were now asking for 10,000 Chinese dollars (about £800),[39][40] and two days later he had again been moved, this time to Jehol.[41] On 8 August the news came that the first group of kidnappers had handed him over to a second group, and the ransom had increased to 100,000 Chinese dollars again.[42] The Chinese and Japanese governments both made an effort to contact the kidnappers.[43]

On 17 August 1935, The Times reported that the Chinese authorities had found Jones's body the previous day with three bullet wounds. The authorities believed that he had been killed on 12 August, the day before his 30th birthday.[40][8] There is a suspicion among some that his murder had been engineered by the Soviet NKVD, as revenge for the embarrassment he had caused the Soviet regime.[8] Others, such as his official biographer Margaret Siriol Colley, point to Japanese involvement.[44] Lloyd George is reported to have said:

That part of the world is a cauldron of conflicting intrigue and one or other interests concerned probably knew that Mr Gareth Jones knew too much of what was going on. He had a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk. I had always been afraid that he would take one risk too many. Nothing escaped his observation, and he allowed no obstacle to turn from his course when he thought that there was some fact, which he could obtain. He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered.[9]

Legacy

[edit]

Memorial

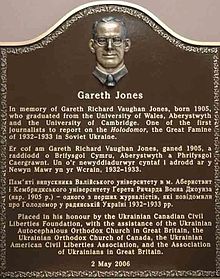

[edit]On 2 May 2006, a trilingual (English/Welsh/Ukrainian) plaque was unveiled in Jones's memory in the Old College at Aberystwyth University, in the presence of his niece Margaret Siriol Colley, and the Ukrainian Ambassador to the UK, Ihor Kharchenko, who described him as an "unsung hero of Ukraine". The idea for a plaque and funding were provided by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, working in conjunction with the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. Dr Lubomyr Luciuk, UCCLA's director of research, spoke at the unveiling ceremony.

In November 2008, Jones and fellow journalist Malcolm Muggeridge were posthumously awarded the Ukrainian Order of Merit at a ceremony in Westminster Central Hall, by Dr Kharchenko, on behalf of Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko for their exceptional service to the country and its people.[45][46]

Another plaque honouring 'Mr Jones' was unveiled at the Merthyr Dyfan Cemetery Chapel in Barry, Wales (30 October 2022), with the support of the Temerty Foundation, the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, and the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation. A final plaque hallowing Mr Jones was placed in the National Library of Ukraine, in Kyiv, on 4 October 2023. The 'political' nature of the plaques has been criticised by members of Jones' family[47].

Diaries

[edit]In November 2009, Jones's diaries recording the Great Soviet Famine of 1932–33, which he described as man-made, went on display for the first time in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge.[25]

Thanks to the support of the Temerty Foundation, the Ukrainian National Women's League of America and the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation, most of the papers of Gareth Jones, including all of his diaries, were digitized and copies were then made available online to scholars and students around the world. The Gareth Jones Papers can be accessed at https://www.llyfrgell.cymru/archifwleidyddolgymreig/gareth-vaughan-jones

Depictions in film

[edit]Serhii Bukovskyi's 2008 Ukrainian film The Living is a documentary about the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33 and Jones' reporting of it.[48][49] The Living premiered 21 November 2008 at the Kyiv Cinema House. It was screened in February 2009 at the European Film Market, in spring 2009 at the Ukrainian Film Festival in Cologne, and in November 2009 at the Second Annual Cambridge Festival of Ukrainian Film.[25][50][51] It received the 2009 Special Jury Prize Silver Apricot in the International Documentary Competition at the Sixth Golden Apricot International Film Festival in July 2009 and the 2009 Grand Prize of Geneva in September 2009.[50][51][52]

In 2012, the documentary film Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones, directed by George Carey, was broadcast on the BBC series Storyville.[53][54][55] It has subsequently been screened in select cinemas.[56][57][58]

The 2019 Ukrainian feature film Mr Jones, starring James Norton and directed by Agnieszka Holland, focuses solely on Jones' investigation and reporting of the famine as it affected Soviet Ukraine. In January 2019, it was selected to compete for the Golden Bear at the 69th Berlin International Film Festival.[59] The film won Grand Prix Golden Lions at the 44th Gdynia Film Festival in September 2019.[60]

Commemoration

[edit]The cities of Dnipro, Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kremenchuk have Gareth Jones Street. There is Gareth Jones Lane in the cities of Dnipro and Kropyvnytskyi.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Timothy Snyder 2010, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin: "The basic facts of mass hunger and death, although sometimes reported in the European and American press, never took on the clarity of an undisputed event. Almost no one claimed that Stalin meant to starve Ukrainians to death; even Adolf Hitler preferred to blame the Marxist system. It was controversial to note that starvation was taking place at all. Gareth Jones did so in a handful of newspaper articles; it seems that he was the only one to do so in English under his own name… Though the journalists knew less than the diplomats, most of them understood that millions were dying from hunger. … Aside from Jones, the only journalist to file serious reports in English was Malcolm Muggeridge, writing anonymously for the Manchester Guardian. He wrote that the famine was "one of the most monstrous crimes in history, so terrible that people in the future will scarcely be able to believe that it happened."[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "Gareth Jones' Relative: Russia Repeating Repressive 1930s Famine Methods".

- ^ https://www.garethjones.org/published_articles/soviet_articles/hungersnot_in_russland.htm

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Otten, Rivka (4 April 2019). "Gareth Jones: Reviled and Forgotten" (PDF). Leiden University. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Famine Exposure: Newspaper Articles relating to Gareth Jones' trips to The Soviet Union (1930–35)". garethjones.org. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "The Price of Russia's 'Plan': Virtual Breakdown of Agriculture". From our Moscow Correspondent. The Manchester Guardian. 12 January 1933, pp. 9–10. The "Moscow correspondent" was Malcolm Muggeridge.

"The Soviet and the Peasantry. An Observer's Notes. I: Famine in North Caucasus". The Manchester Guardian. 25 March 1933, pp. 13–14. (Again, the "Observer" was Muggeridge. This and the following two articles were smuggled out of Russia in a diplomatic bag.)

"The Soviet and the Peasantry. An Observer's Notes. II: Hunger in the Ukraine". The Manchester Guardian. 27 March 1933, pp. 9–10.

"The Soviet and the Peasantry. An Observer's Notes. III: Poor Harvest in Prospect". The Manchester Guardian. 28 March 1933, pp. 9–10.

Carynnyk, Marco (November 1983). "The Famine the Times Couldn't Find". Commentary.

Taylor, Sally J. (2003). "A Blanket of Silence: The Response of the Western Press Corps in Moscow to the Ukraine Famine of 1932–33". In Isajiw, Wsevolod W. (ed.). Famine-genocide in Ukraine, 1932–1933: Western Archives, Testimonies and New Research. Toronto: Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre. ISBN 978-0-921537-56-4. OCLC 495790721.

- ^ a b Taylor 2003.

- ^ a b c d "Journalist Gareth Jones' 1935 murder examined by BBC Four". BBC News. 5 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Jones: The man who knew too much". BBC Cambridgeshire, 13 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Mr. Gareth Jones: Journalist and Linguist". The Times. 17 August 1935. Issue 47145, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Mark (12 November 2009). "1930s journalist Gareth Jones to have story retold". The Guardian.

- ^ "Annie Gwen Jones". garethjones.org.

- ^ "'Unsung hero' reporter remembered". BBC News. 2 May 2006.

- ^ Stewart, H. F. (19 August 1935). "Mr. Gareth Jones". The Times. Issue 47146, p. 15.

- ^ Jones, Gareth (31 March 1933). "Famine Rules Russia". Evening Standard.

- ^ Colley, Margaret Siriol. "The Welsh Wizard, David Lloyd George employs Gareth Jones". garethjones.org. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Series B7. Press cuttings of articles written by Gareth Jones". National Library of Wales. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Gamache, Ray (23 June 2013). "Welsh witness to Russian catastrophe". Institute of Welsh Affairs. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b Jones, Gareth (28 February 1933). "With Hitler across Europe". The Western Mail and South Wales News. Cardiff, Wales.

- ^ Simkin, John. "Gareth Jones". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Colley, Margaret Siriol (9 November 2003). "For The Record: Relatives of Gareth Jones write letter to Times publisher". The Ukrainian Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 46.

- ^ "Reporting Stalin's Famine: Jones and Muggeridge: A Case Study in Forgetting and Rediscovery". Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Colley, Philip. "My great-uncle's legacy must be preserved, but not at the expense of the truth" (PDF). GarethJonesSociety.org. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "Welsh journalist who exposed a Soviet tragedy". Wales Online, Western Mail and the South Wales Echo. 13 November 2009.

- ^ Jones, Gareth (29 March 1933). "Famine Grips Russia Millions Dying, Idle on Rise, Says Briton". GarethJones.org. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "Overview 1933". GarethJones.org. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b Duranty, Walter (31 March 1933). "RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING; Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched. LARGER CITIES HAVE FOOD Ukraine, North Caucasus and Lower Volga Regions Suffer From Shortages. KREMLIN'S 'DOOM' DENIED Russians and Foreign Observers In Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster". The New York Times. p. 13.

- ^ "The New York Times, Friday March 31st 1933: Russians Hungry, But Not Starving". Colley.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 March 2003.

- ^ Snyder 2010, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Jones, Gareth (11 April 1933). "The Balance Sheet of the Five Year Plan". Financial News. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ Jones, Gareth (13 May 1933). "Mr. Jones Replies; Former Secretary of Lloyd George Tells of Observations in Russia". The New York Times. p. 12. Archived from the original on 24 March 2003.

- ^ a b Brown, Mark (13 November 2009). "1930s journalist Gareth Jones to have story retold". the Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Beal, Fred (1938). Word From Nowhere: The Story of a Fugitive from Two Worlds. London: The Right Book Club. p. 287.

- ^ Disler, Mathew (2018). "This Crusading Socialist Taught America's Workers to Fight—in 1929". Narratively. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Colley, Margaret (8 April 2011). "Welsh journalist Gareth Jones "had an unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered"". WalesOnline. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Journalists Held To Ransom". The Times. 30 July 1935. Issue 47129, p. 14.

- ^ "Message From Mr. Gareth Jones". The Times. 2 August 1935. Issue 47132, p. 11.

- ^ "Lower Ransom Asked For Mr. Gareth Jones". The Times. 5 August 1935. Issue 47134, p. 9.

- ^ a b "Mr. Gareth Jones: Murder by Bandits". The Times. 17 August 1935. Issue 47145, p. 10.

- ^ " Mr. Jones Carried into Jehol". The Times. 7 August 1935. Issue 47136, p. 9.

- ^ "Mr. Jones in Hands of New Bandits". The Times. 9 August 1935. Issue 47138, p. 10.

- ^ "Efforts to Release Mr. Jones". The Times. 12 August 1935. Issue 47140, p. 9.

- ^ Colley, Margaret Siriol (2001), the Manchukuo Incident, ISBN 978-0-9562218-0-3, published by Nigel Linsan Colley

- ^ "Ukraine to honour Welsh reporter". BBC Wales. 22 November 2008.

- ^ Hunter, Ian (22 November 2008). "Telling the truth about the Ukrainian famine". The National Post. Toronto, Canada. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009.

- ^ https://www.jewishvoiceforlabour.org.uk/article/famine-was-widespread-under-stalin-why-do-we-only-know-about-ukraines/

- ^ "Live – a film about Holodomor by Sergey Bukovsky". Ukrainian Film Office. 29 October 2008.

- ^ "The Living Historical Documentary Premiered, Ordered by Ukraine 3000 International Charitable Foundation". International Charitable Fund "Ukraine 3000". 21 November 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ a b "The Second Annual Cambridge Festival of Ukrainian Film". Eventbrite. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Ukrainian Studies Film Festival". Cambridge Ukrainian Studies. Cambridge University. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "The Winners of 6th Golden Apricot". GAIFF. 19 July 2009. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ "Collections Search". Collections search. British Film Institute. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Hitler, Stalin and Mr Jones, BBC. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Tom Birchenough, "Storyville: Hitler, Stalin, and Mr. Jones", The arts desk. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Hitler, Stalin And Mr Jones + Q&A – Film Review and Listings". LondonNet. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Hitler, Stalin and Mr. Jones". Regent Street Cinema. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Hitler, Stalin, and Mr. Jones". Frontline Club. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Selection for Competition and Berlinale Special Completed". Berlinale. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- ^ "Mr. Jones tames the Golden Lions at the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia". Cineuropa. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Ray Gamache: Gareth Jones : eyewitness to the Holodomor, Cardiff : Welsh Academic Press, 2018, ISBN 978-1-86057-128-2

External links

[edit]- Gareth Jones commemorative website

- Supplemental to the Gareth Jones commemorative website

- Bukovsky's The Living website

- Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association website

- Short biography of Gareth Jones by his niece, Margaret Siriol Colley. Includes links to newspaper articles written by Jones from around the world.

- "'Unsung hero' reporter remembered". BBC News. 2 May 2006. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- New Release – Tell Them We Are Starving: The 1933 Diaries of Gareth Jones (Kashtan Press, 2015)

- Gareth Vaughan Jones Collection, National Library of Wales

- 1905 births

- 1935 deaths

- Alumni of Aberystwyth University

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- British expatriates in the Soviet Union

- British people murdered abroad

- Deaths by firearm in China

- Holodomor

- Journalists killed while covering military conflicts

- Assassinated British journalists

- People from Barry, Vale of Glamorgan

- People murdered in China

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Ukraine), 3rd class

- Unsolved murders in China

- Welsh journalists

- People assassinated in the 20th century

- British anti-communists