Gunpowder weapons in the Song dynasty

| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

|

Gunpowder weapons in the Song dynasty included fire arrows, gunpowder lit flamethrowers, soft shell bombs, hard shell iron bombs, fire lances, and possibly early cannons known as "eruptors". The eruptors, such as the "multiple bullets magazine eruptors" (bǎi-zi lián zhū pào, 百子連珠炮), consisting of a tube of bronze or cast iron that was filled with about 100 lead balls,[1] and the "flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor" (fēi yún pī-lì pào, 飛雲霹靂炮), were early cast-iron proto-cannons that did not include single shots that occluded the barrel (thus called "co-viative" weapons). The use of proto-cannon, and other gunpowder weapons, enabled the Song dynasty to ward off its generally militarily superior enemies—the Khitan led Liao, Tangut led Western Xia, and Jurchen led Jin—until its final collapse under the onslaught of the Mongol forces of Kublai Khan and his Yuan dynasty in the late 13th century.

History

[edit]

Fire arrow

[edit]The first fire arrows (huǒyào 火藥) were arrows strapped with gunpowder incendiaries, but in 969 two Song generals, Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng (馮繼升), invented a variant fire arrow which utilized gunpowder tubes as propellants.[2] Afterwards fire arrows started transitioning to rocket propelled weapons rather than being fired from a bow.[2] These fire arrows were shown to the emperor in 970 when the head of a weapons manufacturing bureau sent Feng Jisheng to demonstrate the gunpowder arrow design, for which he was heavily rewarded.[3]

In 975, the state of Wuyue sent to the Song dynasty a unit of soldiers skilled in the handling of fire arrows. In the same year, the Song dynasty used fire arrows and incendiary bombs to destroy the fleet of Southern Tang.[4]

In 994, the Liao dynasty attacked the Song and laid siege to Zitong with 100,000 troops. They were repelled with the aid of fire arrows.[4] In 1000 a soldier by the name of Tang Fu (唐福) also demonstrated his own designs of gunpowder arrows, gunpowder pots (a proto-bomb which spews fire), and gunpowder caltrops, for which he was richly rewarded as well.[3] The imperial court took great interest in the progress of gunpowder developments and actively encouraged as well as disseminated military technology. For example, in 1002 a local militia man named Shi Pu (石普) showed his own versions of fireballs and gunpowder arrows to imperial officials. They were so astounded that the emperor and court decreed that a team would be assembled to print the plans and instructions for the new designs to promulgate throughout the realm.[3] The Song court's policy of rewarding military innovators was reported to have "brought about a great number of cases of people presenting technology and techniques" (器械法式) according to the official History of Song.[3] Production of gunpowder and fire arrows heavily increased in the 11th century as the court centralized the production process, constructing large gunpowder production facilities, hiring artisans, carpenters, and tanners for the military production complex in the capital of Kaifeng. One surviving source circa 1023 lists all the artisans working in Kaifeng while another notes that in 1083 the imperial court sent 100,000 gunpowder arrows to one garrison and 250,000 to another.[3] Evidence of gunpowder in the Liao dynasty and Western Xia is much sparser than in Song, but some evidence such as the Song decree of 1073 that all subjects were henceforth forbidden from trading sulfur and saltpeter across the Liao border, suggests that the Liao were aware of gunpowder developments to the south and coveted gunpowder ingredients of their own.[3] A text written by Song Minqiu prior to his death in 1079 includes a gunpowder factory under the Arsenals Administration:

Apart from the Offices of the Eight Workshops (Ba Zuo Si), there are also other (government factories), notably the Workshops for General Siege Train Material (Guang Bi Gong Cheng Zuo), and now both of these, Eastern and Western, are under the authority of the Arsenals Administration (Guang Bi Li Jun Qi Jian). Their work comprises ten departments, item, the gunpowder factory (huo yao zuo), item, the pitch, resin and charcoal department (li qing zuo), item, the fierce fire oil laboratory (meng huo you zuo), item, the metal shop (jin zuo), item, the incendiaries plant (huo zuo), item, the joinery for timber large and small (da xiao mu zuo), item, the foundry for stoves large and small (da xiao lu zuo), item, the leather yard (pi zuo), item, the hemp ropewalk (ma zuo), item, the brick and pottery kilns (yao zi zuo).

All these have their regular specifications and procedures, so that those in charge can learn them by heart. But it is absolutely forbidden to divulge the text to outsiders.[5]— Dong Jing Ji (Records of the Eastern Capital) by Song Minqiu (d. 1079)

-

Fire arrow launchers as depicted in the Wubei Zhi (1621). The launcher is constructed using basketry.

-

A "charging leopard pack" arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi.

-

A "nest of bees" (yī wō fēng 一窩蜂) arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. So called because of its hexagonal honeycomb shape.

-

A "long serpent enemy breaking" fire arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. It carries 32 medium small poisoned rockets and comes with a sling to carry on the back.

-

The 'convocation of eagles chasing hare' rocket launcher from the Wubei Zhi. A double-ended rocket pod that carries 30 small poisoned rockets on each end for a total of 60 rockets. It carries a sling for transport.

-

The 'divine fire arrow screen' from the Huolongjing. A stationary arrow launcher that carries one hundred fire arrows.

Flamethrower

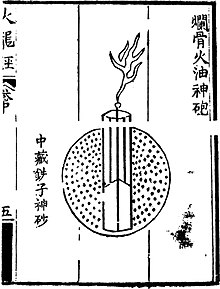

[edit]The Chinese flamethrower, known as the Fierce-fire Oil Cabinet, was recorded to have been used in 976 AD when Song naval forces confronted the Southern Tang fleet on the Changjiang. Southern Tang forces attempted to use flamethrowers against the Song navy, but were accidentally consumed by their own fire when violent winds swept in their direction.[6]

According to the Wujing Zongyao, gunpowder was used to ignite the flamethrower:

Before use the tank is filled with rather more than three catties of the oil with a spoon through a filter (sha luo); at the same time gunpowder (composition) (huo yao) is placed in the ignition chamber (huo lou) at the head. When the fire is to be started one applies a heated branding iron (to the ignition chamber), and the piston-rod is forced fully into the cylinder—then the man at the back is ordered to draw the piston rod (za zhang) fully backwards and work it (back and forth) as vigorously as possible. Whereupon the oil (the petrol) comes out through the ignition chamber and is shot forth as blazing flame.[7]

The flamethrower was a well known device by the 11th century when it was joked that Confucian scholars knew it better than the classics.[6] Both gunpowder and the fierce fire oil were produced under the Arsenals Administration of the Song dynasty.[8] In the early 12th century AD, Kang Yuzhi recorded his memories of military commanders testing out fierce oil fire on a small lakelet. They would spray it about on the opposite bank that represented the enemy camp. The flames would ignite into a sheet of flame, destroying the wooden fortifications, and even killing the water plants, fishes and turtles.[9]In 1126 AD, Li Gang used flamethrowers in an attempt to prevent the Jurchens from crossing the Yellow River.[10] Illustrations and descriptions of mobile flamethrowers on four-wheel push carts were documented in the Wujing Zongyao, written in 1044 AD (its illustration redrawn in 1601 as well).

Explosives

[edit]

The Jurchen people of Manchuria united under Wanyan Aguda and established the Jin dynasty in 1115. Allying with the Song, they rose rapidly to the forefront of East Asian powers and defeated the Liao dynasty in a short span of time. Remnants of the Liao fled to the west and became known as the Qara Khitai, or Western Liao to the Chinese. In the east, the fragile Song-Jin alliance dissolved once the Jin saw how badly the Song army had performed against Liao forces. The Jin grew tired of waiting and captured all five of the Liao capitals themselves. They proceeded to make war on Song, initiating the Jin-Song Wars. This was the first time two major powers would have access to equally formidable gunpowder weapons.[11]

Initially the Jin expected their campaign in the south to proceed smoothly given how poorly the Song had fared against the Liao. However they were met with stout resistance upon besieging Kaifeng in 1126 and faced the usual array of gunpowder arrows and fire bombs, but also a weapon called the "thunderclap bomb" (霹靂炮), which one witness wrote, "At night the thunderclap bombs were used, hitting the lines of the enemy well, and throwing them into great confusion. Many fled, screaming in fright."[11] The thunderclap bomb was previously mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao, but this was the first recorded instance of its use. Its description in the text reads thus:

The thunderclap bomb contains a length of two or three internodes of dry bamboo with a diameter of 1.5 in. There must be no cracks, and the septa are to be retained to avoid any leakage. Thirty pieces of thin broken porcelain the size of iron coins are mixed with 3 or 4 lb of gunpowder, and packed around the bamboo tube. The tube is wrapped within the ball, but with about an inch or so protruding at each end. A (gun)powder mixture is then applied all over the outer surface of the ball.[12]

Jin troops withdrew with a ransom of Song silk and treasure but returned several months later with their own gunpowder bombs manufactured by captured Song artisans.[11] According to historian Wang Zhaochun, the account of this battle provided the "earliest truly detailed descriptions of the use of gunpowder weapons in warfare."[11] Records show that the Jin utilized gunpowder arrows and trebuchets to hurl gunpowder bombs while the Song responded with gunpowder arrows, fire bombs, thunderclap bombs, and a new addition called the "molten metal bomb" (金汁炮).[13] As the Jin account describes, when they attacked the city's Xuanhua Gate, their "fire bombs fell like rain, and their arrows were so numerous as to be uncountable."[13] The Jin captured Kaifeng despite the appearance of the molten metal bomb and secured another 20,000 fire arrows for their arsenal.[13]

The Ming dynasty scholar Mao Yuanyi states in his Wubei Zhi, written in 1628:

The Song people used the turntable trebuchet, the single-pole trebuchet and the squatting-tiger trebuchet. They were all called 'fire trebuchets' because they were used to project fire-weapons like the (fire-)ball, (fire-)falcon, and (fire-)lance. They were the ancestors of the cannon.[14]

The molten metal bomb appeared again in 1129 when Song general Li Yanxian (李彥仙) clashed with Jin forces while defending a strategic pass. The Jin assault lasted day and night without respite, using siege carts, fire carts, and sky bridges, but each assault was met with Song soldiers who "resisted at each occasion, and also used molten metal bombs. Wherever the gunpowder touched, everything would disintegrate without a trace."[15]

Fire lance

[edit]The fire lance, as implied by the name, is essentially a long spear or pole affixed with a tube of gunpowder, and as it saw more usage, the tube's length became longer and pellets were added to the composition. The earliest confirmed employment of the fire lance in warfare was by Song dynasty forces against the Jin in 1132 during the siege of De'an (modern Anlu, Hubei Province).[16][17][18]

The Jin attacked with wooden siege towers called "sky bridges": "As the sky bridges became stuck fast, more than ten feet from the walls and unable to get any closer, [the defenders] were ready. From below and above the defensive structures they emerged and attacked with fire lances, striking lances, and hooked sickles, each in turn. The people [i.e., the porters] at the base of the sky bridges were repulsed. Pulling their bamboo ropes, they [the porters] ended up drawing the sky bridge back in an anxious and urgent rush, going about fifty paces before stopping."[19] The surviving porters then tried once again to wheel the sky bridges into place but Song soldiers emerged from the walls in force and made a direct attack on the sky bridge soldiers while defenders on the walls threw bricks and shot arrows in conjunction with trebuchets hurling bombs and rocks. The sky bridges were also set fire to with incendiary bundles of grass and firewood. Li Heng, the Jin commander, decided to lift the siege and Jin forces were driven back with severe casualties.[19]

The siege of De'an marks an important transition and landmark in the history of gunpowder weapons as the fire medicine of the fire lances were described using a new word: "fire bomb medicine" (火炮藥), rather than simply "fire medicine." This could imply the use of a new more potent formula, or simply an acknowledgement of the specialized military application of gunpowder.[19] Peter Lorge suggests that this "bomb powder" may have been corned, making it distinct from normal gunpowder.[20] Evidence of gunpowder firecrackers also points to their appearance at roughly around the same time fire medicine was making its transition in the literary imagination.[21] Fire lances continued to be used as anti-personnel weapons into the Ming dynasty, and were even attached to battle carts on one situation in 1163. Song commander Wei Sheng constructed several hundred of these carts known as "at-your-desire-war-carts" (如意戰車), which contained fire lances protruding from protective covering on the sides. They were used to defend mobile trebuchets that hurled fire bombs.[19]

By the 1270s, Song cavalrymen were using fire lances as mounted weapons as evidenced by the account of a Song-Yuan battle in which two fire lance armed Song cavalrymen rushed a Chinese officer of Bayan of the Baarin.[22]

Naval bombs

[edit]Gunpowder technology also spread to naval warfare and in 1129 Song decreed that all warships were to be fitted with trebuchets for hurling gunpowder bombs.[19] Older gunpowder weapons such as fire arrows were also utilized. In 1159 a Song fleet of 120 ships caught a Jin fleet at anchor near Shijiu Island (石臼島) off the shore of Shandong peninsula. The Song commander "ordered that gunpowder arrows be shot from all sides, and wherever they struck, flames and smoke rose up in swirls, setting fire to several hundred vessels."[21] Song forces took another victory in 1161 when Song paddle boats ambushed a Jin transport fleet, launched thunderclap bombs, and drowned the Jin force in the Yangtze.[21]

The men inside them paddled fast on the treadmills, and the ships glided forwards as though they were flying, yet no one was visible on board. The enemy thought that they were made of paper. Then all of a sudden a thunderclap bomb was let off: It was made with paper (carton) and filled with lime and sulphur. (Launched from trebuchets) these thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames. The carton case rebounded and broke, scattering the lime to form a smoky fog which blinded the eyes of men and horses so that they could see nothing. Our ships then went forward to attack theirs, and their men and horses were all drowned, so that they were utterly defeated.[23]

— Hai Qiu Fu

According to a minor military official by the name of Zhao Wannian (趙萬年), thunderclap bombs were used again to great effect by the Song during the Jin siege of Xiangyang in 1206–1207. Both sides had gunpowder weapons, but the Jin troops only used gunpowder arrows for destroying the city's moored vessels. The Song used fire arrows, fire bombs, and thunderclap bombs. Fire arrows and bombs were used to destroy Jin trebuchets. The thunderclap bombs were used on Jin soldiers themselves, causing foot soldiers and horsemen to panic and retreat. "We beat our drums and yelled from atop the city wall, and simultaneously fired our thunderclap missiles out from the city walls. The enemy cavalry was terrified and ran away."[24] The Jin were forced to retreat and make camp by the riverside. The Song then made a successful offensive on Jin forces and conducted a night assault using boats. They were loaded with gunpowder arrows, thunderclap bombs, a thousand crossbowmen, five hundred infantry, and a hundred drummers. Jin troops were surprised in their encampment while asleep by loud drumming, followed by an onslaught of crossbow bolts, and then thunderclap bombs, which caused a panic of such magnitude that they were unable to even saddle themselves and trampled over each other trying to get away. Two to three thousand Jin troops were slaughtered along with eight to nine hundred horses.[24][25]

Competing with gunpowder empires

[edit]

Hard-shell explosives

[edit]Traditionally the inspiration for the development of the iron bomb is ascribed to the tale of a fox hunter named Iron Li. According to the story, around the year 1189 Iron Li developed a new method for hunting foxes which used a ceramic explosive to scare foxes into his nets. The explosive consisted of a ceramic bottle with a mouth, stuffed with gunpowder, and attached with a fuse. Explosive and net were placed at strategic points of places such as watering holes frequented by foxes, and when they got near enough, Iron Li would light the fuse, causing the ceramic bottle to explode and scaring the frightened foxes right into his nets. While a fanciful tale, it's not exactly certain why this would cause the development of the iron bomb, given the explosive was made using ceramics, and other materials such as bamboo or even leather would have done the same job, assuming they made a loud enough noise.[26]

The invention of hard shell explosives did not occur in the Song dynasty. Instead it was introduced to them by the northern Jurchen Jin dynasty in 1221 during the siege of Qizhou (in modern Hubei province). The Song commander Zhao Yurong (趙與褣) survived and was able to relay his account for posterity.

Qizhou was a major fortress city situated near the Yangtze and a 25 thousand strong Jin army advanced on it in 1221. News of the approaching army reached Zhao Yurong in Qizhou, and despite being outnumbered nearly eight to one, he decided to hold the city. Qizhou's arsenal consisted of some three thousand thunderclap bombs, twenty thousand "great leather bombs" (皮大炮), and thousands of gunpowder arrows and gunpowder crossbow bolts. While the formula for gunpowder had become potent enough to consider the Song bombs to be true explosives, they were unable to match the explosive power of the Jin iron bombs. Yurong describes the uneven exchange thus, "The barbaric enemy attacked the Northwest Tower with an unceasing flow of catapult projectiles from thirteen catapults. Each catapult shot was followed by an iron fire bomb [catapult shot], whose sound was like thunder. That day, the city soldiers in facing the catapult shots showed great courage as they maneuvered [our own] catapults, hindered by injuries from the iron fire bombs. Their heads, their eyes, their cheeks were exploded to bits, and only one half [of the face] was left."[27] Jin artillerists were able to successfully target the command center itself: "The enemy fired off catapult stones ... nonstop day and night, and the magistrate's headquarters [帳] at the eastern gate, as well as my own quarters ..., were hit by the most iron fire bombs, to the point that they struck even on top of [my] sleeping quarters and [I] nearly perished! Some said there was a traitor. If not, how would they have known the way to strike at both of these places?"[27] Zhao was able to examine the new iron bombs himself and described thus, "In shape they are like gourds, but with a small mouth. They are made with pig iron, about two inches thick, and they cause the city's walls to shake."[27] Houses were blown apart, towers battered, and defenders blasted from their placements. Within four weeks all four gates were under heavy bombardment. Finally the Jin made a frontal assault on the walls and scaled them, after which followed a merciless hunt for soldiers, officers, and officials of every level. Zhao managed an escape by clambering over the battlement and making a hasty retreat across the river, but his family remained in the city. Upon returning at a later date to search the ruins, he found that the "bones and skeletons were so mixed up that there was no way to tell who was who."[27]

Eruptors and cannons

[edit]The early fire lance, considered to be the ancestor of firearms, is not considered a true gun because it did not include projectiles. Later on, shrapnel such as ceramics and bits of iron were added, but these didn't occlude the barrel, and were only swept along with the discharge rather than make use of windage. These projectiles were called "co-viatives."[15] The commonplace nature of the fire lance, if not in quantity, was apparent by the mid 13th century, and in 1257 an arsenal in Jiankang Prefecture reported the manufacture of 333 "fire emitting tubes" (突火筒). In 1259 a type of "fire-emitting lance" (突火槍) made an appearance and according to the History of Song: "It is made from a large bamboo tube, and inside is stuffed a pellet wad (子窠). Once the fire goes off it completely spews the rear pellet wad forth, and the sound is like a bomb that can be heard for five hundred or more paces."[28][29][30][31][32] The pellet wad mentioned is possibly the first true bullet in recorded history depending on how bullet is defined, as it did occlude the barrel, unlike previous co-viatives used in the fire lance.[28]

Fire lances transformed from the "bamboo- (or wood- or paper-) barreled firearm to the metal-barreled firearm"[28] to better withstand the explosive pressure of gunpowder. From there it branched off into several different gunpowder weapons known as "eruptors" in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, with different functions such as the "filling-the-sky erupting tube" which spewed out poisonous gas and porcelain shards, the "orifice-penetrating flying sand magic mist tube" (鑽穴飛砂神霧筒) which spewed forth sand and poisonous chemicals into orifices, and the more conventional "phalanx-charging fire gourd" which shot out lead pellets.[28] The character for lance, or spear (槍), has continued to refer to both the melee weapon and the firearm into modern China, perhaps as a reminder of its original form as simply a tube of gunpowder tied to a spear.

According to Jiao Yu in his Huolongjing (mid 14th century), an early Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the 'flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor' (fei yun pi-li pao) was used in the following fashion:

The shells are made of cast iron, as large as a bowl and shaped like a ball. Inside they contain half a pound of 'magic' gunpowder. They are sent flying towards the enemy camp from an eruptor; and when they get there a sound like a thunder-clap is heard, and flashes of light appear. If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze…[33]

Traditionally the first appearance of the hand cannon is dated to the late 13th century, just after the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty.[34] However a sculpture depicting a figure carrying a gourd shaped hand cannon was discovered among the Dazu Rock Carvings in 1985 by Robin D. S. Yates. The sculptures were completed roughly 250 km northwest of Chongqing by 1128, after the fall of Kaifeng to the Jin dynasty. If the dating is correct this would push back the appearance of the cannon in China by a hundred years more than previously thought.[35] The bulbous nature of the cannon is congruous with the earliest hand cannons discovered in China and Europe.

Archaeological samples of the gun, specifically the hand cannon (huochong), have been dated starting from the 13th century. The oldest extant gun whose dating is unequivocal is the Xanadu Gun, so called because it was discovered in the ruins of Xanadu, the Mongol summer palace in Inner Mongolia. The Xanadu Gun is 34.7 cm in length and weighs 6.2 kg. Its dating is based on archaeological context and a straightforward inscription whose era name and year corresponds with the Gregorian Calendar at 1298. Not only does the inscription contain the era name and date, it also includes a serial number and manufacturing information which suggests that gun production had already become systematized, or at least become a somewhat standardized affair by the time of its fabrication. The design of the gun includes axial holes in its rear which some speculate could have been used in a mounting mechanism. Like most early guns with the possible exception of the Western Xia gun, it is small, weighing just over six kilograms and thirty-five centimeters in length.[36] Although the Xanadu Gun is the most precisely dated gun from the 13th century, other extant samples with approximate dating likely predate it.

One candidate is the Heilongjiang hand cannon, discovered in 1970, and named after the province of its discovery, Heilongjiang, in northeastern China.[37][38] It is small and light like the Xanadu gun, weighing only 3.5 kilograms, 34 cm (Needham says 35 cm), and a bore of approximately 2.5 cm.[39] Based on contextual evidence, historians believe it was used by Yuan forces against a rebellion by Mongol prince Nayan in 1287. The History of Yuan states that a Jurchen commander known as Li Ting led troops armed with hand cannons into battle against Nayan.[40]

The Ningxia gun was found in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region by collector Meng Jianmin (孟建民). This Yuan dynasty firearm is 34.6 cm long, the muzzle 2.6 cm in diameter, and weighs 1.55 kilograms. The firearm contains a transcription reading, "Made by bronzesmith Li Liujing in the year Zhiyuan 8 (直元), ningzi number 2565" (銅匠作頭李六徑,直元捌年造,寧字二仟伍百陸拾伍號).[41] Similar to the Xanadu Gun, it bears a serial number 2565, which suggests it may have been part of a series of guns manufactured. While the era name and date corresponds with the Gregorian Calendar at 1271 CE, putting it earlier than both the Heilongjiang Hand Gun as well as the Xanadu Gun, but one of the characters used in the era name is irregular, causing some doubt among scholars on the exact date of production.[41]

Another specimen, the Wuwei Bronze Cannon, was discovered in 1980 and may possibly be the oldest as well as largest cannon of the 13th century: a 100 centimeter 108 kilogram bronze cannon discovered in a cellar in Wuwei, Gansu Province containing no inscription, but has been dated by historians to the late Western Xia period between 1214 and 1227. The gun contained an iron ball about nine centimeters in diameter, which is smaller than the muzzle diameter at twelve centimeters, and 0.1 kilograms of gunpowder in it when discovered, meaning that the projectile might have been another co-viative.[42] Ben Sinvany and Dang Shoushan believe that the ball used to be much larger prior to its highly corroded state at the time of discovery.[43] While large in size, the weapon is noticeably more primitive than later Yuan dynasty guns, and is unevenly cast. A similar weapon was discovered not far from the discovery site in 1997, but much smaller in size at only 1.5 kg.[44] Chen Bingying disputes this however, and argues there were no guns before 1259, while Dang Shoushan believes the Western Xia guns point to the appearance of guns by 1220, and Stephen Haw goes even further by stating that guns were developed as early as 1200.[41] Sinologist Joseph Needham and renaissance siege expert Thomas Arnold provide a more conservative estimate of around 1280 for the appearance of the "true" cannon.[45][46] Whether or not any of these are correct, it seems likely that the gun was born sometime during the 13th century.[44]

Late Song gunpowder weaponry

[edit]

By the mid 13th century, gunpowder weapons were available to both the Mongols and the Song. The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui Province) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers."[47] These bombs were apparently quite large. "Several hundred men hurled one bomb, and if it hit the tower it would immediately smash it to pieces."[47] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a famous local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.[47] Perhaps as another point of military interest, the account of this battle also mentions that the Anfeng defenders were equipped with a type of small arrow to shoot through eye slits of Mongol armor, as normal arrows were too thick to penetrate.[47]

In 1257 the Song official Li Zengbo was dispatched to inspect frontier city arsenals. Li considered an ideal city arsenal to include several hundred thousand iron bombshells, and also its own production facility to produce at least a couple thousand a month. The results of his tour of the border were severely disappointing and in one arsenal he found "no more than 85 iron bomb-shells, large and small, 95 fire-arrows, and 105 fire-lances. This is not sufficient for a mere hundred men, let alone a thousand, to use against an attack by the ... barbarians. The government supposedly wants to make preparations for the defense of its fortified cities, and to furnish them with military supplies against the enemy (yet this is all they give us). What chilling indifference!"[48] Fortunately for the Song, Möngke Khan died in 1259 and the war would not continue until 1269 under the leadership of Kublai Khan, but when it did the Mongols came in full force.

Blocking the Mongols' passage south of the Yangtze were the twin fortress cities of Xiangyang and Fancheng. What resulted was one of the longest sieges the world had ever known, lasting from 1268 to 1273. For the first three years the Song defenders had been able to receive supplies and reinforcements by water, but in 1271 the Mongols set up a full blockade with a formidable navy of their own, isolating the two cities. This didn't prevent the Song from running the supply route anyway, and two men with the surname Zhang did exactly that. The Two Zhangs commanded a hundred paddle wheel boats, travelling by night under the light of lantern fire, but were discovered early on by a Mongol commander. When the Song fleet arrived near the cities, they found the Mongol fleet to have spread themselves out along the entire width of the Yangtze with "vessels spread out, filling the entire surface of the river, and there was no gap for them to enter."[49] Another defensive measure the Mongols had taken was the construction of a chain, which stretched across the water.[49] The two fleets engaged in combat and the Song opened fire with fire-lances, fire-bombs, and crossbows. A large number of men died trying to cut through chains, pull up stakes, and hurl bombs, while Song marines fought hand to hand using large axes, and according to the Mongol record, "on their ships they were up to the ankles in blood."[50] With the rise of dawn, the Song vessels made it to the city walls and the citizens "leapt up a hundred times in joy."[50] In 1273 the Mongols enlisted the expertise of two Muslim engineers, one from Persia and one from Syria, who helped in the construction of counterweight trebuchets. These new siege weapons had the capability of throwing larger missiles further than the previous traction trebuchets. One account records, "when the machinery went off the noise shook heaven and earth; every thing that [the missile] hit was broken and destroyed."[50] The fortress city of Xiangyang fell in 1273.[15]

The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers. It was probably the largest army the Mongols had ever utilized. Such an army was still unable to successfully storm Song city walls, as seen in the 1274 Siege of Shayang. Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven."[15] Shayang was captured and its inhabitants massacred.[15]

Gunpowder bombs were used again in the 1275 Siege of Changzhou in the latter stages of the Mongol-Song Wars. Upon arriving at the city, Bayan gave the inhabitants an ultimatum: "if you ... resist us ... we shall drain your carcasses of blood and use them for pillows."[15] This didn't work and the city resisted anyway, so the Mongol army bombarded them with fire bombs before storming the walls, after which followed an immense slaughter claiming the lives of a quarter million.[15] The war lasted for only another four years during which some remnants of the Song held up last desperate defenses. In 1277, 250 defenders under Lou Qianxia conducted a suicide bombing and set off a huge iron bomb when it became clear defeat was imminent. Of this, the History of Song writes, "the noise was like a tremendous thunderclap, shaking the walls and ground, and the smoke filled up the heavens outside. Many of the troops [outside] were startled to death. When the fire was extinguished they went in to see. There were just ashes, not a trace left."[51][52] So came an end to the Mongol-Song Wars, which saw the deployment of all the gunpowder weapons available to both sides at the time, which for the most part meant gunpowder arrows, bombs, and lances, but in retrospect, another development would overshadow them all, the birth of the gun.[28]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 263-364.

- ^ a b Liang 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrade 2016, p. 32.

- ^ a b Needham 1986f, p. 148.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 93.

- ^ a b Needham 1986f, p. 88-89.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 82-83.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 94.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 90.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Andrade 2016, p. 34.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g Andrade 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 222.

- ^ Chase 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 33-34.

- ^ a b c d e Andrade 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Lorge 2008, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 227.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 166.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 168–169.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Andrade 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e Andrade 2016, p. 51.

- ^ Partington 1960, p. 246.

- ^ Bodde, Derk (1987). Charles Le Blanc, Susan Blader (ed.). Chinese ideas about nature and society: studies in honour of Derk Bodde. Hong Kong University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-962-209-188-7. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

The other was the 'flame-spouting lance' (t'u huo ch'iang). A bamboo tube of large diameter was used as the barrel (t'ung), ... sending the objects, whether fragments of metal or pottery, pellets or bullets, in all directions

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen; McBride, Angus (1980). Angus McBride (ed.). The Mongols (illustrated, reprint ed.). Osprey Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-85045-372-0. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

In 1259 Chinese technicians produced a 'fire-lance' (huo ch' iang): gunpowder was exploded in a bamboo tube to discharge a cluster of pellets at a distance of 250 yards. It is also interesting to note the Mongol use of suffocating fumes produced by burning reeds at the battle of Liegnitz in 1241.

- ^ Saunders, John Joseph (2001). The history of the Mongol conquests (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

In 1259 Chinese technicians produced a 'fire-lance' (huo ch'iang): gunpowder was exploded in a bamboo tube to discharge a cluster of pellets at a distance of 250 yards. We are getting close to a barrel-gun.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 264.

- ^ Patrick 1961, p. 6.

- ^ Lu 1988.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 52-53.

- ^ Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press, p. 32, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, p. 293, ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 53.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 293-4.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 329.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 53-54.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 330.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Needham 1986f, p. 10.

- ^ Arnold 2001, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Andrade 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 47-48.

- ^ a b Andrade 2016, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Andrade 2016, p. 50-51.

- ^ Partington 1960, p. 250, 244, 149.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 978-0-304-35270-8

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521842263

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Chase, Kenneth Warren (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9

- Chaffee, John W. (2015), The Cambridge History of China Volume 5 Part Two Sung China, 960-1279, Cambridge University Press

- Chia, Lucille (2011), Knowledge and Text Production in an Age of Print: China, 900-1400, Brill

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, OTTO HARRASSOWITZ · WIESBADEN

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H.M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7.

- Graff, David Andrew and Robin Higham (2002). A Military History of China. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Herman, John E. (2007), Amid the Clouds and Mist China's Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700, Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-02591-2

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6.

- Knapp, Ronald G. (2008), Chinese Bridges: Living Architecture From China's Past. Singapore, Tuttle Publishing

- Kuhn, Dieter (2009), The Age of Confucian Rule, Harvard University Press

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lorge, Peter (2005), War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-96929-8

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29 (3): 594–605, doi:10.2307/3105275, JSTOR 3105275, S2CID 112733319

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009), The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mote, F. W. (2003), Imperial China: 900–1800, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674012127

- Needham, Joseph (1986a), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986g), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 1, Physics, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986b), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986c), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986d), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986e), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts, Taipei: Caves Books

- —— (1986h), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1, Botany, Cambridge University Press

- —— (1986f), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Needham, Joseph (2008), Science & Civilisation in China Volume 5 Part 11, Cambridge University Press

- Nicolle, David (2003), Medieval Siege Weapons (2): Byzantium, the Islamic World & India AD 476-1526, Osprey Publishing

- Pacey, Arnold (1991), Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-year History, MIT Press

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons.

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press.

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Reilly, Kevin (2012), The Human Journey: A Concise Introduction to World History, Volume 1, Rowman & Littlefield

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Rubinstein, Murray A. (1999), Taiwan: A New History, East Gate Books

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T'ang Exotics, University of California Press

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 978-957-32-0876-1

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Standen, Naomi (2007), Unbounded Loyalty Frontier Crossings in Liao China, University of Hawai'i Press

- Taylor, K.W. (2013), A History of the Vietnamese, Cambridge University Press

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612-1300, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 960-1644, Osprey Publishing

- Twitchett, Denis C. (1979), The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 3, Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Cambridge University Press

- Twitchett, Denis (1994), "The Liao", The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6, Alien Regime and Border States, 907-1368, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–153, ISBN 0521243319

- Twitchett, Denis (2009), The Cambridge History of China Volume 5 The Sung dynasty and its Predecessors, 907-1279, Cambridge University Press

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012), East Asia: A New History, AuthorHouse

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002), Imperial Chinese Military History, Writers Club Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015), Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press, ISBN 9780674088467

- Wright, David (2005), From War to Diplomatic Parity in Eleventh Century China, Brill

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005), HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PRE-DYNASTIC KHITAN, Institute for Asian and African Studies 7

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7

- Yule, Henry (1915), Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route, Hakluyt Society