Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam

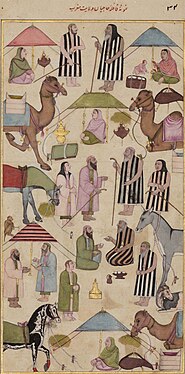

17th- or 18th-century Hajj certificate showing the Kaaba within the Masjid al-Haram | |

| Date | 26 January – 15 April 2012[1] |

|---|---|

| Venue | British Museum |

| Type | Art exhibition |

| Theme | Hajj |

Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam was an exhibition held at the British Museum in London from 26 January to 15 April 2012. It was the world's first major exhibition telling the story, visually and textually, of the hajj – the pilgrimage to Mecca which is one of the five pillars of Islam. Textiles, manuscripts, historical documents, photographs, and art works from many different countries and eras were displayed to illustrate the themes of travel to Mecca, hajj rituals, and the Kaaba. More than two hundred objects were included, drawn from forty public and private collections in a total of fourteen countries. The largest contributor was David Khalili's family trust, which lent many objects that would later be part of the Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage.

The exhibition was formally opened by Prince Charles in a ceremony attended by Prince Abdulaziz bin Abdullah, son of King Abdullah, the custodian of the Two Holy Mosques. It was popular both with Muslims and non-Muslims, attracting nearly 120,000 adult visitors and favourable press reviews. This success inspired the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the Arab World Institute in Paris, the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam to stage their own hajj-themed exhibitions with contributions from the Khalili Collection.

An exhibition catalogue with essays about the hajj, edited by Venetia Porter, was published by the British Museum in 2012, along with a shorter illustrated guide to the hajj. An academic conference, linked to the exhibition, resulted in another book about the topic.

Background: The Hajj[edit]

The hajj (Arabic: حَجّ) is an annual pilgrimage to the sacred city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia,[2] the holiest city for Muslims. It is a mandatory religious duty that must be carried out at least once in their lifetime by all adult Muslims who are physically and financially capable of undertaking the journey, and can support their family during their absence.[3][4] At the time of the exhibition, the journey was being made by three million pilgrims each year.[5]

The hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam, along with shahadah (confession of faith), salat (prayer), zakat (charity), and sawm (fasting). It is a demonstration of the solidarity of the Muslim people, and their submission to God (Allah).[4][6] The word "hajj" means "to attend a journey", which connotes both the outward act of a journey and the inward act of intentions.[7] In the centre of the Masjid al-Haram mosque in Mecca is the Kaaba, a black cubic building known in Islam as the House of God.[8][3] A hajj consists of several distinct rituals including the tawaf (procession seven times anticlockwise round the Kaaba), wuquf (a vigil at Mount Arafat where Mohammed is said to have preached his last sermon), and ramy al-jamarāt (stoning of the Devil).[3][9] Of the five pillars, the hajj is the only one not open to non-Muslims,[10] since Mecca is restricted to Muslims only.[11] Over the centuries, the hajj and its destination the Kaaba have inspired creative works in many media, including literature, folk art, and photography.[2]

Preparation and launch[edit]

There had been no previous major exhibitions devoted to the hajj.[12][11][13] The British Museum's planning for its exhibition spanned a two-year period.[10] This included research projects funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.[14][15] The lead curator was Venetia Porter and the project curator was Qaisra Khan, both staff of the British Museum.[11][16][12] Curators negotiated for public and private collections to loan objects for display; forty collections from fourteen countries contributed more than two hundred objects.[17] The largest contributor was David Khalili's family trust.[18] Preparation for the event included promotion to Muslim communities.[10] Khan collected photographs, recordings, and souvenirs during her own hajj in 2010,[12][19][20] and assisted with community outreach.[10]

The exhibition was presented in partnership with the King Abdulaziz Public Library and with the support of HSBC Amanah.[15][11] Prince Charles gave a speech to formally open the exhibition on 26 January 2012. Prince Abdulaziz bin Abdullah travelled from Saudi Arabia to represent his father, the custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, at this opening ceremony.[21]

Content[edit]

The exhibition was held in the circular British Museum Reading Room.[22] To set the mood, visitors entered through a narrow passage where audio recordings of an adhan (call to prayer) were played.[23] The displays were arranged to draw visitors around the circular space, mimicking the tawaf: the anticlockwise walk around the Kaaba that is a core ritual of the hajj.[24] An early section illustrated the preparations traditionally taken before a hajj, which can include settling debts and preparing a will. Before trains and air travel, a hajj pilgrimage could take many months and involve a significant risk of death either from transmissible disease or bandits.[24] Also displayed in this section were examples of ihram clothing: white clothes that mark the spiritual purpose and collective unity of hajj pilgrims.[25]

The bulk of the content was organised around three themes: pilgrimage routes, the rituals of the hajj, and Mecca.[22] The first section described five different pilgrimage routes towards Mecca: the traditional routes through Arabia, North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, and Asia, plus the modern route by air from Britain. It thus contrasted the early pilgrims' arduous, risky journey across desert or ocean with the ease of modern travel.[25][11]

Pilgrimages of past centuries were illustrated by manuscripts of hajj-related literature, including the Anis Al-Hujjaj, the Dala'il al-Khayrat, the Shahnameh, the Futuh al-Haramayn, and the Jami' al-tawarikh.[26] Mansa Musa, king of the Mali Empire, travelled to Mecca in 1324 with 60,000 courtiers as atonement for accidentally killing his mother; he was depicted in a panel from a 14th-century Catalan Atlas.[27][5] The importance of Mecca to Muslims was illustrated by these ancient maps and diagrams as well as by qibla compasses which help devotees turn towards the city, which they are required to do for prayer.[24][28]

The stories of individual historical pilgrims were told through diaries and photographs. These included Westerners such as the explorer Richard Francis Burton (a non-Muslim who made the trip in disguise in 1853),[5] intelligence officer Harry St John Philby, and aristocrat Lady Evelyn Cobbold.[12] Philby took part in cleaning the Kaaba on his trip, and the brush and cloth he used were included in the exhibition.[29] The King of Bone's diary, written in the Bugis language, was one of several objects from pilgrims who travelled from what is now Indonesia.[30][11] Other texts included a travelogue by the 19th-century Chinese scholar Ma Fuchu and a 13th-century manuscript of the Maqamat al-Hariri story collection.[26] One of the earliest surviving Qurans was on display: an 8th-century manuscript lacking the decorative calligraphy associated with later versions.[13]

A seven-minute video illustrated the rituals of the hajj.[25] The rituals section also displayed textiles from the holy sites,[25] including sections from kiswahs (ornate textile coverings that had decorated the Kaaba), sitaras (ornamental curtains) from other holy sites[26] and a mahmal (ceremonial litter conveyed by camel from Cairo to Mecca with the pilgrim caravan).[30] Some exhibits were personal items that pilgrims brought or acquired on their journey. These included prayer beads, travel tickets, and flasks for drinking water from the Zamzam Well. Also displayed were hajj certificates, showing that a hajj has been completed, often with illustrations of holy sites. Hajj banknotes can be bought before the journey and exchanged for Saudi currency, protecting the pilgrim from exchange rate fluctuations.[26]

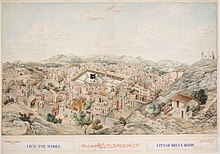

The section on Mecca used past and present photographs and paintings to show how the mosque surrounding the Kaaba (the Masjid al-Haram) has been modernised to make space for much larger numbers of pilgrims, resulting in some ancient buildings being demolished.[25] The 19th-century photographs included some by Muhammad Sadiq of holy sites in Mecca and Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje's portraits of pilgrims.[26]

Towards the end of the exhibition were several pieces of contemporary art, including works by Ahmed Mater, Idris Khan, Walid Siti, Kader Attia, Ayman Yossri, and Abdulnasser Gharem.[31][24][26][29] A final section played audio testimonies of British hajj pilgrims[10] and invited guests to write down their own reflections.[11]

-

Illustration of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina from the Dala'il al-Khayrat, late 17th or 18th century

-

Chamfron for a horse, Ottoman Empire, 18th century

-

Section from the kiswah of the Maqam Ibrahim, Cairo, 19th century

Reception and legacy[edit]

The museum's target of 80,000 visitors was quickly exceeded. By the end of the run, 119,948 adult tickets had been sold (children had free entry and were not counted).[10] According to the British Museum's annual report, educational events connected to the exhibition attracted nearly 32,000 participants.[32] Forty-seven percent of visitors were Muslims.[33] Some non-Muslim visitors reported that overhearing Muslim families' conversations or striking up conversations with them, helped them appreciate the spiritual importance of the hajj.[25]

In surveys, 89% of attendees reported emotional or spiritual reactions such as reflection on faith.[34] Steph Berns, a doctoral researcher at the University of Kent, interviewed attendees and found a small minority for whom contemplating the artefacts or personal testimonies induced a sense of closeness to God.[35] The aspects of the exhibition most often remarked on by visitors were the personal accounts of hajj pilgrims in the video, photographs, and textual diaries.[25] The artifacts that attracted the most visitor comments were the textiles and contemporary art pieces.[36] Berns observed that, for most visitors, the exhibition could not fully reproduce the personal and emotional experience of the hajj, which is crucially connected to the specific location of Mecca. She described this as an unavoidable result of presenting the topic within a museum thousands of miles away.[25]

In The Guardian, Jonathan Jones wrote "This is one of the most brilliant exhibitions the British Museum has put on", awarding it five stars out of five. He described its celebration of Islam as "challenging" to non-Muslim Westerners used to negative portrayal of the religion.[31] The Londonist praised an "eye-opening and fascinating" exhibition that demystified an aspect of Islam poorly understood by most of the public.[23] Brian Sewell in the Evening Standard described the exhibition as "of profound cultural importance", praising it as an example of "what multiculturalism should be – information, instruction and understanding, academically rigorous, leaving both cultures (the enquiring and the enquired) intact".[37] For The Diplomat, Amy Foulds described the first part of the exhibition as very interesting but felt that the section about Mecca was anti-climactic, though somewhat redeemed by the contemporary art pieces.[11] Reviewing for The Arts Desk, Fisun Guner awarded four out of five stars to "an exhibition about faith that even an avowed atheist might find rather moving [...] as we read and listen to the words of believers experiencing what must be seen for them not only as an encounter with God but a deep sense of connection with fellow Muslims".[24] For The Independent, Arifa Akbar, who went on hajj in 2006, found it "utterly refreshing" to see a focus on personal experiences of the hajj rather than the politics of Islam and how it is perceived by non-Muslims. She observed that a museum visit is unavoidably dry compared to the intense experience of joining the throng around the Kaaba, but praised the curators' originality and courage in tackling the subject. For Akbar, the highlights included the 8th-century Quran and a sitara.[13] Also in The Independent, Jenny Gilbert found the logistical details of travel – a "dry" topic for those not already interested in manuscript maps – less appealing than the colourful accounts of historical and modern pilgrims.[5]

The journalist and broadcaster Sarfraz Manzoor took his 78-year-old mother to the exhibition since she had long wanted to perform the hajj but was too infirm to make the trip. He contrasted his mother's joyous reaction against his own mixed feelings on the subject matter as a British Muslim. "And yet", he wrote, "the exhibition does illuminate the magnetic appeal of the hajj – of knowing that hundreds of millions have visited the site and completed the same rituals."[38] The scholar of religion Karen Armstrong recommended the exhibition as an antidote to Western stereotypes of Islam that focus on violence and extremism. She described it as an insight into how the vast majority of Muslims view and practise their religion.[39] For the Sunday Times art critic Waldemar Januszczak, an exhibition on a topic for which there is relatively little visual material was "heroic" and showed a determination to help visitors understand the world. He drew a parallel with exhibitions of conceptual art; since texts rather than visual art played a crucial role, "so much of the extraordinary story line laid out for us [...] takes place in the mind". Among the visual art, he singled out the textiles as providing "a visceral artistic buzz to the display".[29]

In Newsweek, Jason Goodwin said the exhibition fulfilled the British Museum's purpose of "explain[ing] the world to itself" but said that Saudi influence resulted in "a palpable air of self-congratulation and a tendency to soft-pedal the role of the Ottoman Turks in maintaining the major hajj routes across their empire from the 16th to the 20th centuries."[30] Nick Cohen, in an Observer piece accusing British cultural institutions of "selling their souls" to dictatorships, criticised the exhibition for ignoring aspects of the hajj documented by historians of Islam. He speculated that topics had been excluded so as not to offend the Saudi royal family, including deaths at the hajj (by violence or by incompetent crowd control) and the destruction of buildings in Mecca where Mohammad and his family had lived.[40] The museum responded that the Saudi royal family had not funded the exhibition and had no curatorial control.[10] Jonathan Jones responded to Cohen, defending the five-star review he had given. For Jones, the exhibition was driven not by political or theological goals but by a genuine enthusiasm for the beauty and significance of Islamic culture. That some exhibits had come from Saudi Arabia was, in his view, not significant.[41]

-

Illustration of a North African pilgrim caravan from the Anis Al-Hujjaj, 17th century

-

Mahmal cover in red silk, late 19th century

-

Section from the curtain of the prophet's tomb, 18th century

Publications[edit]

Two books resulted directly from the exhibition, both edited by Venetia Porter. Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam is an exhibition catalogue that also includes interdisciplinary essays explaining the history, culture, and religious significance of the hajj. The authors include Karen Armstrong, Muhammad Abdel-Haleem, Hugh N. Kennedy, Robert Irwin, and Ziauddin Sardar. The Art of Hajj is a shorter book describing Mecca, Medina, and the rituals of the hajj with visual examples.[1] Qamar Adamjee, a curator at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, described both books as accessible to a broad audience while covering many different aspects of the subject.[1]

An academic conference was held in conjunction with the exhibition from 22 to 24 March.[15] Its proceedings, including thirty papers on different aspects of the hajj, were published by the British Museum in 2013 as The Hajj: Collected Essays, edited by Venetia Porter and Liana Saif.[42]

The Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage subsequently expanded into a five-thousand-object collection documenting the Islamic holy sites of Mecca and Medina. In 2022 it was published in a single illustrated volume by Qaisra Khan, who had co-curated the London exhibition and had become the curator of Hajj and the Arts and Pilgrimage at the Khalili Collections.[43][44] An eleven-volume catalogue is scheduled for publication in 2023.[45]

Related exhibitions[edit]

The success of Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam prompted museums and art institutions in other countries to inquire about hosting hajj-themed exhibitions. It was not possible for the London exhibition to go on tour; it had involved special loans from 40 different sources, arranged by years of negotiation. Instead, these institutions created exhibitions on the theme of the hajj using items loaned by the Khalili Collection, among other collections.[46][47] These included the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Arab World Institute in Paris. The Doha exhibition was titled Hajj: The Journey Through Art and drew most of its content from Qatari art collections. Since France has many North African immigrants, the Paris exhibition focused on hajj routes from North Africa.[46] A Dutch exhibition titled Longing for Mecca: The Pilgrim's Journey was held in 2013 at the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden and in an expanded version at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam from January 2019 to February 2020. This combined objects from Dutch collections with the Khalili Collection objects that had been exhibited in London.[48]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Adamjee, Qamar (16 May 2013). "Review of "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam" by Venetia Porter and "The Art of Hajj" by Venetia Porter". Caa.reviews. College Art Association. doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2013.51. ISSN 1543-950X.

- ^ a b Piscatori, James (19 January 2012). "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam". Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Long, Matthew (2011). Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures. Tarrytown, N.Y.: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-7614-7926-0. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 0-253-21627-3.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Jenny (29 January 2012). "Hajj: Journey to the heart of Islam, British Museum, London". The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Hooker, M. B. (2008). Indonesian Syariah: Defining a National School of Islamic Law. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 228. ISBN 978-981-230-802-3.

- ^ Adelowo, E. Dada, ed. (2014). Perspectives in Religious Studies: Volume III. Ibadan, Nigeria: HEBN Publishers Plc. p. 395. ISBN 978-978-081-447-2.

- ^ Wensinck, A. J. & Jomier, J. (1978). "Kaʿba". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 317–322. OCLC 758278456.

- ^ Zaki, Yousra (7 August 2019). "What is Hajj? A simple guide to Islams annual pilgrimage". Gulf News. GN Media. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Hajj – Journey to the Heart of Islam". Kashmir Observer. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Foulds, Amy (27 February 2012). "Journey to the Heart of Islam". The Diplomat. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, Maev (25 January 2012). "Hajj exhibition at British Museum". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Akbar, Arifa (20 January 2012). "Pilgrim's progress: Journey to the Heart of Islam". The Independent. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ Porter 2012, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Porter, Venetia (Winter 2011). "Spiritual Journey". British Museum Magazine (71). British Museum Friends: 22–25. ISSN 0965-8297.

- ^ Porter 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Porter 2012, pp. 7, 275.

- ^ Moore, Susan (12 May 2012). "A leap of faith". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Khan, Qaisra (Winter 2011). "Journey of a Lifetime". British Museum Magazine (71). British Museum Friends: 26–27. ISSN 0965-8297.

- ^ Khan, Qaisra M. (2013). "Souvenirs and Gifts: Collecting Modern Hajj". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj: collected essays. London. pp. 228–240. ISBN 978-0-86159-193-0. OCLC 857109543.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the opening of the "HAJJ: Journey to the heart of Islam" exhibition at the British Museum". Prince of Wales. 26 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam". Time Out London. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b Khan, Tabish (28 January 2012). "Exhibition Review: Hajj: Journey To The Heart Of Islam @ The British Museum". Londonist. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Guner, Fisun (21 February 2012). "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum". The Arts Desk. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Berns, Steph (2012). "Hajj Journey to the heart of Islam". Material Religion. 8 (4): 543–544. doi:10.2752/175183412X13522006995213. ISSN 1743-2200. S2CID 192190977.

- ^ a b c d e f Porter 2012, pp. 272–275.

- ^ Porter 2012, p. 154.

- ^ Esposito, John L. (2003). "Salat". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512558-0. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Januszczak, Waldemar (29 January 2012). "The stuff that dreams are made of". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Goodwin, Jason (20 February 2012). "The British Museum's 'Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam'". Newsweek. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ a b Jones, Jonathan (25 January 2012). "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ British Museum (2012). The British Museum report and accounts for the year ended 31 March 2012 (PDF). London: The Stationery Office. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-10-297619-9. OCLC 1117090767.

- ^ Morris Hargreaves McIntyre & July 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Morris Hargreaves McIntyre & July 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Berns 2015, p. 174.

- ^ Berns 2015, p. 151.

- ^ Sewell, Brian (16 June 2015). "Hajj – journey to the heart of Islam, British Museum – review". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Manzoor, Sarfraz (9 March 2012). "How the British Museum brought the hajj to my mum". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, Karen (22 January 2012). "Prejudices about Islam will be shaken by this show". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Nick (18 March 2012). "Keep corrupt regimes out of British culture". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (19 March 2012). "The British Museum's Hajj takes us on a pilgrimage, not a propaganda journey". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ^ "The Hajj: collected essays". WorldCat. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ Maisey, Sarah (11 July 2022). "New book shows 300 illustrations of the Hajj pilgrimage over the centuries". The National. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Assouline takes readers to the heart of Hajj in new tome". Arab News. 8 July 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage". Khalili Collections. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ a b Mishkhas, Abeer (26 July 2013). "The British Museum's Hajj exhibition inspires Paris, Leiden and Doha". Asharq Al-Awsat. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ "The Eight Collections". Nasser David Khalili. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Tamimi Arab, Pooyan (26 May 2020). "Longing for Mecca (Verlangen naar Mekka): Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam (February 2019 – January 2020)". Material Religion. 16 (3): 394–396. doi:10.1080/17432200.2020.1775420. ISSN 1743-2200. S2CID 221062579.

Sources[edit]

- Berns, Steph (2015). "Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam" (PDF). Sacred Entanglements: studying interactions between visitors, objects and religion in the museum (PhD). University of Kent. pp. 136–175. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- Morris Hargreaves McIntyre (2012). "Bridging cultures, sharing experiences: An evaluation of Hajj: journey to the heart of Islam at the British Museum" (PDF). British Museum. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Porter, Venetia, ed. (2012). Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1176-6. OCLC 745332856.

External links[edit]

- Video about the exhibition by The Financial Times

- Gallery of photos from the exhibition, the Khalili Collections