Hall of Mental Cultivation

| Hall of Mental Cultivation | |

|---|---|

| Native names | |

Outside the Hall | |

| Location | The Forbidden City |

| Nearest city | Beijing |

| Coordinates | 39°55′06″N 116°23′22″E / 39.91835°N 116.38940°E |

| Built | 1537 |

| Original use | Residence of the emperor, governance, administration |

| Rebuilt | During the Qing dynasty |

| Restored by | The Palace Museum, Beijing |

| Current use | Tourist destination |

| Governing body | The Palace Museum, Beijing |

The Hall of Mental Cultivation (simplified Chinese: 养心殿; traditional Chinese: 養心殿; pinyin: Yǎngxīn Diàn, Manchu: ᠶᠠᠩ

ᠰᡳᠨ

ᡩᡳᠶᠠᠨ yang sin diyan) is a building in the inner courtyard of the Forbidden City in Beijing, China. The hall is a wooden structure with dome coffered ceilings, and was first built during the Ming dynasty in 1537, and was reconstructed during the Qing dynasty.[1] During the early Qing dynasty under the reign of the Kangxi Emperor the hall was mostly used as a workshop, wherein artisan objects like clocks were designed and manufactured.[1][2][3] From the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor during the 18th century, the hall was the residence for the emperor.[1] Under the reign of the Qianlong Emperor until the fall of the Qing dynasty, the hall became the centre of governance and political administration.[1] In the Western Warmth Chamber, the emperor would hold private meetings, and discuss state affairs with his mandarins.[1] After the death of Emperor Xianfeng, from inside the Eastern Warmth Chamber, empress dowagers Ci'an and Cixi would hold audiences with ministers and rule from behind a silk screen curtain during their regencies for emperors Tongzhi and Guangxu, who both succeeded to the throne as children in the second half of the 19th century.[1][4]

The Hall of Mental Cultivation contained the Hall of Three Rarities, which stored art and cultural relics, and the Qianlong Emperor's collection of 134 model calligraphy works from the Imperial Collection.[1][5] He also housed three ancient calligraphy artworks by ancient calligraphers Wang Xizhi, Wang Xianzhi and Wang Xun.[6][7]

The hall's interior is decorated with polychrome paintings, glazed tiles, ancient thangkas, and traditional wax paper decorations. From 2006, the Palace Museum instigated a research and conservation project aimed at restoring the hall, and preserving its cultural relics like thangkas.[8]

In anticipation of the hall's closure due to restoration in 2018, in 2017 the Palace Museum launched a digital exhibition about the Hall of Mental Cultivation.[9]

History

[edit]Construction concluded in 1537, during the 16th year of the Ming dynasty's Jiajing Emperor's reign, which spanned from 1521 to 1566.[1] During the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661–1722) during the early Qing dynasty, the Hall of Mental Cultivation was primarily used as an imperial workshop of the 'Inner Court', or atelier for the newly established administrative body called the Department of Imperial Household Construction, or Zaobanchu.[1][2][10] The Zaobanchu were responsible for manufacturing arts and crafts objects, "court utensils and paraphernalia."[2][3] Such craft studios within the hall, established in 1693, stored "clocks, jade, arms and maps" and was dedicated to Chinese artisans who influenced and helped European crusaders in developing their glass and enamel craft techniques.[3] From 1691, most of these craft workshops and ateliers were transferred to the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility Archived 2022-01-21 at the Wayback Machine (Cining gong) which was built in 1536.[10]

Use and purpose

[edit]Ever since the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor from 1723 to 1735, the main purpose of the Hall of Mental Cultivation was to house the emperor.[1] The Yongzheng Emperor moved from the Palace of Heavenly Purity to the Hall of Mental Cultivation, since he felt uncomfortable sleeping inside the place where his father died.[11] The hall also became the main vicinity where he carried out his administrative and political duties.[1] It was up until 1912 after the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor who ascended to the throne in 1908, that the Hall of Mental Cultivation stood as the political hub of the Qing dynasty.[1]

During the early years of the Yongzheng Emperor's reign, part of the hall was dedicated to constructing clocks, many of which were designed by European artisans.[12] The emperor would often describe his desired function and design of the clock, which would then be sketched then constructed, according to the emperor's specifications, and always subject to his approval.[12]

Western Warmth Chamber

[edit]Also known as a nuange, the western warmth chamber was found inside the Hall of Mental Cultivation's front hall.[1] During the Qianlong Emperor's reign during the middle-late Qing dynasty, this room became the epicentre of such political and governmental activities.[1] The emperor would read memorials and hold private meetings with his ministerial members.[13][1] A private prayer room for the Qianlong Emperor which was also known as the Buddha Room which was two storeys tall, was also constructed in 1747.[8][1]

Hall of Three Rarities

[edit]Constructed within the Hall's Western Warmth Chamber, the Hall of Three Rarities or Sanxitang was the Qianlong Emperor's study and was also dedicated to housing what are now deemed to be artistic and cultural relics.[1] Inside this room, the Qianlong Emperor kept his calligraphy artworks.[5] In particular, he stored three works by three significant calligraphers: Timely Clearing After Snowfall by Wang Xizhi from the Jin dynasty, Mid-Autumn by his son Wang Xianzhi, and Letter to Boyuan by Wang Xun, Xizhi's nephew.[6][14][7] Whilst keeping the original works, in 1747, the Qianlong Emperor ordered for these works as well as 134 other calligraphic works from the Imperial Collection to be carved into stone, and displayed in the nearby Pavilion of Reviewing the Past, or Yueguo lou in Beihai Park, Beijing.[7][15] Some of these calligraphic works formally housed within the Hall of Three Rarities are now archived in a collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, titled the Model Calligraphies of the Hall of Three Rarities.

Timely Clearly After Snowfall

[edit]Written as a running script, this artwork depicts a short letter, written by Xizhi to his friend after a snowfall.[16] According to the critic Chan Ching-fen from the Ming dynasty, the running script depicted in this artwork influenced the calligraphic style of Chao Meng-fu, a calligrapher from the Yuan dynasty.[16]

Mid-Autumn

[edit]This model calligraphy made of bamboo, employs a cursive script (Chinese: 草書; pinyin: cǎoshū) and only has 22 Chinese characters. After the fall of Chinese imperialism, the work was sold from the private, royal collections by dowager Jingyi, the consort of Emperor Tongzhi.[17] However, in the 1950s under the orders of Premier Zhou Enlai, China's Ministry of Culture re-acquired this work, together with Letter to Boyuan by Wang Xun.[17][18] This artwork is now displayed at the Palace Museum.

Eastern Warmth Chamber

[edit]This area of the hall was dedicated to Empress Dowagers Cixi and Ci'an.[1] It was in this room, that during the late Qing dynasty after the death of her husband Emperor Xianfeng, Empress Dowager Cixi ruled China from "behind a silk screen curtain", engaging in official state affairs through and behind her son, the child emperor Tongzhi and the following emperor Guangxu.[4][19][1]

From 1862 to 1866, while ruling behind the curtain and the child emperor Tongzhi, Empress Dowagers Cixi and Ci'an were also lectured about peaceful governance by academics from the Hanlin Academy.[20] Using the biographies of former emperors and empresses as the blueprint for political success, these lectures were dedicated to teaching the two Empress Dowagers about how to effectively rule China.[20]

Western Side Hall

[edit]This area of the Hall of Mental Cultivation was dedicated to the "consecration of tablets of deceased emperors."[1]

Eastern Side Hall

[edit]This area served as a common Buddhist prayer hall.[1]

Hall of Joyful Swallows

[edit]Found inside the rear hall inside the Hall of Mental Cultivation, the Hall of Joyful Swallows was reserved for the emperor's high-ranking concubines.[1]

Gate of Mental Cultivation

[edit]The Gate of Mental Cultivation or Yangxinmen, was constructed in front of the Hall and faced southwards, and could originally only be opened to the emperor.[21] Buildings in front of the Gate housed and were reserved for the emperor's eunuchs.[1]

Layout

[edit]The Hall of Mental Cultivation is shaped like an 'H', or the Chinese character 'gong' (工) and occupies a space of approximately 3800m2.[22][8] Surrounding the Hall are the Grand Council offices and those of other significant government bodies.[23]

Construction and architecture

[edit]

In a research experiment conducted in 2019 that aimed to uncover the technology utilised in constructing the royal buildings within the Forbidden City, Xu and colleagues discovered that the hall had been constructed with materials like "wood, black bricks, roof tiles and mortar."[22] Wood was a common material in ancient Chinese architecture and was used to frame the Buddha Room, which had cross-shaped wooden walls, partitions, and frames, shaped like zig-zags.[8] The mortar formulated during the construction of the hall contained raw materials like "calcite, quartz, hematite, muscovite, mullite, aragonite and gypsum", and plant fibres like "bamboo, jute, flax, hemp, ramie", and even sticky rice, blood and plant juice.[22]

Inside the main hall's central bay, the domed coffered ceilings exhibited traditional patterns like dragons and golden decorations (douba-zaojing), reflective of the architectural and artistic style that pervaded the Ming dynasty.[1] A product of Confucianism, a zaojing, (Chinese: 藻井; pinyin: zǎojǐng) or coffered ceiling, is shaped in either a square, octagon or circle, and is placed in the centre of the ceiling.[24] It was a common feature in ancient Chinese halls, palaces, religious temples, and physically represented the "unity of heaven and man on the one hand, and a hierarchical society on the other."[24]

Based on archaeological discoveries of Neolithic water wells pertaining to the Hemudu culture within the Yuyao, Zhejiang province, it has been found that the design and physical properties of the zaojing derives from early wooden water well structures.[24] The zaojing's origins have also been linked to the designs of early skylights from ancient Chinese huts, particularly from the early Han dynasty.[24]

Interior design

[edit]

Decorative polychrome paintings

[edit]The decorative polychrome paintings like that of the "ridge tie-beam" of the main hall were created with mineral pigments like azurite and atacamite, and featured patterns and motifs reflective of the artistic style of the ruling dynasty at the time.[1] For instance, during the Jiajing Emperor's sovereignty amid the Ming dynasty, common decorative patterns within such paintings included the fangintoul: a sword tip with straight lines, a lengxian, a three-fold concave lined pattern, spiral flowers, and up-ward turned lotus bases.[1]

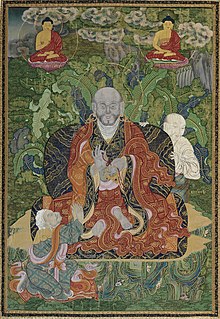

Thangkas

[edit]Thangkas which are cotton or silk artworks painted by Lamas who historically worked inside the Forbidden City were often hung on the wooden walls of the Buddha Room.[8]

Paper-based interior decoration

[edit]The walls and ceilings of the Hall of Mental Cultivation were decorated with many artworks created with biao hu (裱糊) a traditional handmade paper, lajan (蜡笺纸) a traditional handmade wax paper, and tie luo (贴落).[25] A tie luo was a traditional Chinese calligraphy or painting and was popularised during the Qing dynasty where it was often affixed in imperial palaces.[26] Court painters drew the tie luo which was then placed on top of the biao hu paper.[25] Inside the hall was a dragon-embellished tie luo called Longevity (寿), made with lajan.[25]

Restoration and conservation

[edit]Since 2006, the Palace Museum commenced a research and conservation project aimed at maintaining and restoring the Hall of Mental Cultivation.[22]

Given that the hall has rarely been open to the public, its quiet and dusty interior has become prone to widespread pest-breeding.[27] This has made preserving cultural relics a greater challenge, given that such pests target and destroy the relics which are often made with natural, organic material.[27] In a study concerned with the conservation of cultural relics within buildings inside the Forbidden City, over the course of three years, Zhang and colleagues discovered that cultural relics inside the hall were at risk of decay, due to pests like the carpet beetle, silverfish, booklice, clothes moths, and the spider beetle.[27] The relics that were most at risk were "carpets, felts and rafters used as partitions."[27] The Buddha Room, which houses up to 38 thangkas, had the highest concentration of pests, specifically carpet beetles.[27][8] The preservation of thangkas is particularly difficult, since not only insect damage but environmental conditions like changes in winds and temperatures, exposure to light, effects of pollution and dust, paint loss and natural ageing can quickly cause the artworks to tear, wrinkle, or become brittle.[8] The hall's glazed tiling, which was also a common feature in ancient Chinese architecture, has also experienced degradation and poor conservation due to hundreds of years of exposure to constant changes in environmental conditions, particularly rain.[28]

Since September 2018, the Hall of Mental Cultivation has been closed due to such restoration.[29] It was expected that the hall would reopen in 2020.[22]

Digital exhibition

[edit]In October 2017, the Palace Museum launched the digital experience exhibition Discovering the Hall of Mental Cultivation.[9] This exhibition is displayed within the Duanmen Tower, inside the digital display hall called the Duanmen Digital Museum, which was built in 2015.[9] Discovering the Hall of Mental Cultivation is the first digital exhibition in China that integrates ancient architecture, traditional culture and technology.[9]

Discovering the Hall of Mental Cultivation won the Golden Award at the 2018 Festival of Audio-visual Multimedia, an event sponsored by the Committee of International Council of Museums, and Audio-visual International Multimedia.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Yang, Hong; Xie, Jiawei; Ji, Lifang (2018). "The Historical Information of the Decorative Polychrome Painting in the Hall of Mental Cultivation Complex, Forbidden City". Built Heritage. 2 (1): 19–38. doi:10.1186/BF03545700. ISSN 2096-3041.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Emily Byrne (2020). Chinese-Islamic works of art, 1644–1912: a study of some Qing dynasty examples. Lü Xue, Ricardo Joppert. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-00044-0. OCLC 1112787673.

- ^ a b c Moll-Murata, Christine (2018-08-24). "2. The Qing Central Government Institutions in Control of the Handicrafts". State and Crafts in the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911). Amsterdam University Press. pp. 69–108. doi:10.1515/9789048537938-006. ISBN 978-90-485-3793-8. S2CID 239392733.

- ^ a b Zhu, Jianfei (2004). Chinese Spatial Strategies: Imperial Beijing, 1420–1911. Psychology Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-415-31883-9.

- ^ a b Ledderose, Lothar (1998). "Calligraphy at the close of the Chinese Empire". Phoebus: Art at the Close of China's Empire. 8: 189–208.

- ^ a b Huichun, Yu (2009). "Qianlong's Divine Treasures: The Bells in Rhyming-the-Old Hall". Asia Major. 22 (2): 121–144. ISSN 0004-4482. JSTOR 41649979.

- ^ a b c Lauer, Uta (2020). "Venerable Copies: The Afterlife of a Fragment of a Letter by Wang Xizhi (303–361)". Fakes and Forgeries of Written Artefacts from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern China. De Gruyter. pp. 77–88. doi:10.1515/9783110714333-004. ISBN 978-3-11-071433-3. S2CID 240575278.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fang, Xiaoji; Ju, Jianwei; Wang, Jie; Zhang, Rui; Wang, You; Zhou, Qian; Shi, Ningchang; Song, Jirong (2020). "Conservation Challenges for Thangkas in the Buddha Room of the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian), Palace Museum, Beijing". Studies in Conservation. 65 (sup1): 75–79. doi:10.1080/00393630.2020.1768327. ISSN 0039-3630. S2CID 219751295.

- ^ a b c d e Lin, Yuan (2020). "Research on Interactively Digital Display for Cultural Heritage- Discovering the Hall of Mental Cultivation: A Digital Experience Exhibition". Asia-Pacific Journal of Convergent Research Interchange. 6 (8): 51–67. doi:10.47116/apjcri.2020.08.06. ISSN 2508-9080.

- ^ a b "A Magnificent Imperial Falangcai Enamelled Glass Brush Pot". www.christies.com. Retrieved 2021-05-30.

- ^ Gao, Jie (2016). "Symbolism in the Forbidden City: The Magnificent Design, Distinct Colors, and Lucky Numbers of China's Imperial Palace" (PDF). Education About Asia. 21 (3): 9–17.

- ^ a b Chinenova, Vera; Golovin, Alexander; Tyulina, Irina (2012). "The Birth of the Moscow School of Applied Mechanics in the 2nd Half of the 19th Century and the Early 20th Century". In Koetsier, Teun; Ceccarelli, Marco (eds.). Explorations in the History of Machines and Mechanisms. History of Mechanism and Machine Science. Vol. 15. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 39–53. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4132-4_3. ISBN 978-94-007-4132-4.

- ^ Jinghua, Ru; Hualiang, Peng (2012). Palace Architecture: Imperial Palaces of the Last Dynasty. China Architecture and Building Press. ISBN 978-7-112-14121-0.

- ^ "Top 10 calligraphy masterpieces of ancient China – China.org.cn". www.china.org.cn. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ "Letter to Boyuan in Running Script". The Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ a b "Timely Clearing After Snowfall – Wang Xizhi (ca. 303–361)". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ a b "Mid-autumn Manuscript". The Palace Museum. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Yu, Meng (2018). "Approaches to the recovery of Chinese cultural objects lost overseas: a case study from 1949 to 2016". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 24 (6): 741–755. doi:10.1080/10286632.2017.1335720. ISSN 1028-6632. S2CID 157109523.

- ^ "Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908)". academic.mu.edu. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ a b Chan, Ying-kit (2015). "A Precious Mirror for Governing the Peace: A Primer for Empress Dowager Cixi". NAN NÜ. 17 (2): 214–244. doi:10.1163/15685268-00172p02. ISSN 1387-6805.

- ^ "Hall of Mental Cultivation, Yangxindian – Forbidden City, Beijing". www.travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ^ a b c d e Xu, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, P. (2019). "Multi-analytical Studies of the Lime Mortars from the Yanxi Hall in the Yangxin Palace of the Palace Museum (Beijing)". Archaeometry. 61 (2): 309–326. doi:10.1111/arcm.12421. ISSN 1475-4754. S2CID 134441057.

- ^ Zhuoyun, Yu (1984). Palaces of the Forbidden City. New York: Viking Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-670-53721-7. OCLC 9371286.

- ^ a b c d Xie, Jing (2019). "From earth to heaven: the origin and development of zaojing in early China". Architectural Research Quarterly. 23 (4): 349–363. doi:10.1017/S1359135519000307. ISSN 1359-1355. S2CID 214227892.

- ^ a b c Ma, Yue; Ji, Lifang; Lei, Yong (2020). "Materials Used for Paper-based Interior Decoration in the Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian) in the Palace Museum, Beijing". Studies in Conservation. 65 (sup1): 203–204. doi:10.1080/00393630.2020.1753352. ISSN 0039-3630. S2CID 219017471.

- ^ Wei, Le; Chen, Wenjia; Jin, Gaowa; Guo, Zhimou; Wang, Yunli; Kang, Baoqiang; Wang, Na; Gu, An; Zhang, Yun; Lei, Yong (2018). "Scientific analysis of tie luo, a Qing Dynasty calligraphy artifact in the Palace Museum, Beijing, China". Heritage Science. 6 (26). doi:10.1186/s40494-018-0193-2. ISSN 2050-7445.

- ^ a b c d e Zhang, Guoqing; Gu, An; Wei, Le (2020). "Study on Population Dynamics, Occurrence Mechanism and Control Measures of Cultural Relics Pests in the Hall of Mental Cultivation of the Forbidden City". www.researchsquare.com. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-136154/v1. S2CID 234460283. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ^ Adili, Dilireba; Zhao, Jing; Yang, Lu; Zhao, Peng; Wang, Cong; Luo, Hongjie (2020). "Protection of glazed tiles in ancient buildings of China". Heritage Science. 8 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/s40494-020-00380-5. ISSN 2050-7445.

- ^ 毕楠. "Hall of Mental Cultivation in Forbidden City starts official renovation". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hall of Mental Cultivation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hall of Mental Cultivation at Wikimedia Commons