Hayward, California

Hayward | |

|---|---|

|

Top: Holy Sepulcher Church; Portuguese Memorial Park; Hayward Water Tower. Bottom: City Hall; All Saints Church. | |

| Nickname: Haystack | |

| Motto: Heart of the Bay[1] | |

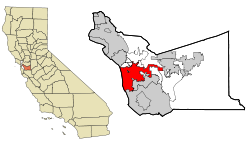

Location of Hayward in Alameda County, California | |

| Coordinates: 37°40′08″N 122°04′51″W / 37.668820°N 122.080796°W[2] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Alameda |

| Incorporated | March 11, 1876[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Mark Salinas[4] |

| • State Senate | Aisha Wahab (D)[5] |

| • Assemblymember | Liz Ortega (D)[6] |

| • U. S. rep. | Eric Swalwell (D)[7] |

| Area | |

• City | 64.06 sq mi (165.92 km2) |

| • Land | 45.77 sq mi (118.56 km2) |

| • Water | 18.29 sq mi (47.36 km2) 28.9% |

| Elevation | 105 ft (32 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 162,954 |

| • Rank | 3rd in Alameda County 36th in California 170th in the United States |

| • Density | 2,500/sq mi (980/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes[11] | 94540–94546, 94552, 94557 |

| Area code | 510, 341 |

| FIPS code | 06-33000 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277607, 2410724 |

| Flower | Carnation[1] |

| Website | www |

Hayward is a city located in Alameda County, California, United States, in the East Bay subregion of the San Francisco Bay Area. With a population of 162,954 as of 2020,[10] Hayward is the sixth largest city in the Bay Area, and the third largest in Alameda County.[12] Hayward was ranked as the 36th most populous municipality in California. It is included in the San Francisco–Oakland–San Jose Metropolitan Statistical Area by the US Census.[13] It is located primarily between Castro Valley, San Leandro and Union City, and lies at the eastern terminus of the San Mateo–Hayward Bridge. The city was devastated early in its history by the 1868 Hayward earthquake. From the early 20th century until the beginning of the 1980s, Hayward's economy was dominated by its now defunct food canning and salt production industries.

Name

[edit]Hayward was originally known as "Hayward's", then as "Haywood", later as "Haywards", and eventually as "Hayward". There is some disagreement as to how it was named. Most historians believe it was named for William Dutton Hayward (1815–1891), who opened a hotel there in 1852.[14] William Hayward eventually became the road commissioner for Alameda County. He used his authority to influence the construction of roads in his own favor. He was also an Alameda County supervisor. The United States Geological Survey's Geographic Names Information System states the city was named after Alvinza Hayward, a millionaire from the California Gold Rush.[15][16] Regardless of which Hayward the area was named for, the name was changed to "Haywood" when the post office was first established in 1860.[17]

In 1876, a town was chartered by the State of California under the name of "Haywards". The name of the post office was then able to change because of the loss of the apostrophe before the "s". This change occurred in 1880.[17] In 1911, the town was officially renamed Hayward, dropping the "s".[18][19] However, the United States Board on Geographic Names would not recognize this name change until 1931.[20]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]Human habitation of the greater East Bay, including Hayward, dates from at least 4000 BC. The most recent pre-European inhabitants of the Hayward area were the Native American Ohlone people.[21]

19th century

[edit]

In the 19th century, the land that is now Hayward became part of Rancho San Lorenzo, a Spanish land grant to Guillermo Castro, in 1841. The site of his home was on the former El Camino Viejo, or Castro Street (now Mission Boulevard) between C and D Streets, but the structure was severely damaged in the 1868 Hayward earthquake, with the Hayward Fault running directly under its location. Most of the city's structures were destroyed in the earthquake, the last major earthquake on the fault. In 1930, that site was chosen for the construction of the City Hall, which served the city until 1969.[22] A post office opened in 1860, followed by the town's incorporation in 1876.[17]

Hayward grew steadily throughout the late 19th century, with an economy based on agriculture and tourism. Important crops were tomatoes, potatoes, peaches, cherries, and apricots. Hunt Brothers Cannery opened in 1895. Chicken and pigeon raising also played important roles in the economy. A rail line between Oakland and San Jose, the South Pacific Coast Railroad, was established but later destroyed in the 1868 earthquake.[24] The Hayward shore of the Bay was developed into extensive salt evaporation ponds, and was one of the most productive areas in the world, with Leslie Salt being one of the largest companies.[25]

20th century

[edit]The San Mateo–Hayward Bridge opened in 1929, connecting the city to the San Francisco Peninsula.[26]

During the 1930s, the Harry Rowell Rodeo Ranch, now within the bounds of Castro Valley, drew rodeo cowboys from across the continent, and Western movie actors such as Slim Pickens and others from Hollywood.[27][28]

Prior to World War II, Hayward had a high concentration of Japanese Americans, who were subject to the Japanese-American internment during the war. The war brought an economic and population boom to the area, as factories opened to manufacture war material. Many of the workers stayed after the end of the war. Two suburban tract housing pioneers, Oliver Rousseau and David D. Bohannon, were prominent builders of postwar housing in the area.[30]

The Hayward Area Recreation and Park District was formed in 1944.

California State University, Hayward opened in the Hayward Hills in 1957. Southland Mall was dedicated in 1964.

The second San Mateo–Hayward Bridge opened in 1967. The City Center Building opened in 1969 and acted as the new city hall until 1989 when the Loma Prieta earthquake damaged the building and forced the city government to move out. The building was closed to the public in 1998, with the new Hayward City Hall opening the same year. The "Bay Area Rapid Transit" system began operating in the Bay Area in 1972, with stations in downtown Hayward and south Hayward.

The Hunt Brothers Cannery closed in 1981.

21st century

[edit]

The city's downtown area was slated for redevelopment in 2012 and 2013, with landscaping, new businesses opening up, and older ones getting façade upgrades.[31]

Warren Hall on the California State University, East Bay campus was demolished in 2013.

The Russell City Energy Center began operating in 2013 at the Hayward shoreline.

In May 2015, the city's former shoreline landfill was declared a site for conversion to a solar farm, set to generate enough electricity to power 1,200 homes. It will be one of 186 sites in the Regional Renewable Energy Procurement Project.[32]

In October 2015, construction began for the Hayward 21st Century Library and Heritage Plaza. The library opened in September 2019, and the plaza was originally expected to open sometime in 2019.[33][34]

Former communities

[edit]Mount Eden was a former city that was incorporated into Hayward in the 1950s, at the same time as Schafer Park.[17][35]

Russell City was a former unincorporated community. It existed from 1853 until 1964. It is now the location of an industrial park. The Russell City Energy Center, a 429-megawatt natural gas-fired power plant built by Calpine, is located there.[36][37]

Stokes Landing, Hayward Heath, and Eden Landing were communities now within Hayward city limits.[17]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 63.7 square miles (165 km2). 45.3 square miles (117 km2) of it is land and 18.4 square miles (48 km2) of it (comprising 28.9%) is water.

The Hayward Fault Zone runs through much of Hayward, including the downtown area. The United States Geological Survey has stated that there is an "increasing likelihood" of a major earthquake on this fault zone, with potentially serious resulting damage.[38]

The San Lorenzo Creek runs through the city.

Hayward borders on many municipalities and communities. The cities bordering on Hayward are San Leandro, Union City, Fremont, and Pleasanton. The census-designated places bordering on Hayward are Castro Valley, San Lorenzo, Cherryland, Sunol, and Fairview.

-

Industrial areas on west side of city

-

South Hayward Hills

-

Hayward, California - South Hayward BART station and surrounding area

-

South Hayward

-

Interchange of Interstate 880 and California State Route 92

Climate

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2015) |

Hayward has a Mediterranean climate, and contains microclimates, both of which are features of the greater Bay Area. In 2012, the USDA rated Hayward as a zone 10A climate.

| Climate data for Hayward, California, 1991-2020 Normals [a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

79 (26) |

84 (29) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

106 (41) |

97 (36) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

107 (42) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.3 (15.2) |

61.9 (16.6) |

64.4 (18.0) |

66.8 (19.3) |

69.3 (20.7) |

74.0 (23.3) |

74.7 (23.7) |

76.4 (24.7) |

77.0 (25.0) |

73.5 (23.1) |

65.1 (18.4) |

59.4 (15.2) |

68.5 (20.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.2 (10.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

58.2 (14.6) |

60.9 (16.1) |

64.6 (18.1) |

66.1 (18.9) |

67.3 (19.6) |

67.3 (19.6) |

63.5 (17.5) |

56.2 (13.4) |

51.2 (10.7) |

59.7 (15.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 43.1 (6.2) |

45.1 (7.3) |

47.4 (8.6) |

49.5 (9.7) |

52.4 (11.3) |

55.1 (12.8) |

57.4 (14.1) |

58.2 (14.6) |

57.6 (14.2) |

53.5 (11.9) |

47.2 (8.4) |

42.9 (6.1) |

50.8 (10.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 22 (−6) |

25 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

41 (5) |

44 (7) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

33 (1) |

26 (−3) |

21 (−6) |

21 (−6) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.91 (74) |

3.11 (79) |

2.35 (60) |

1.20 (30) |

0.58 (15) |

0.15 (3.8) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.08 (2.0) |

0.81 (21) |

1.51 (38) |

3.20 (81) |

16 (406.3) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 165.0 | 182.0 | 251.0 | 281.0 | 314.0 | 330.0 | 300.0 | 272.0 | 267.0 | 243.0 | 189.0 | 156.0 | 2,950 |

| Source 1: NOAA[39] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: The Weather Channel,[40] usclimatedata.com[41] for Sunshine hours data | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 504 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,231 | 144.2% | |

| 1890 | 1,419 | 15.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,965 | 38.5% | |

| 1910 | 2,746 | 39.7% | |

| 1920 | 3,487 | 27.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,530 | 58.6% | |

| 1940 | 6,736 | 21.8% | |

| 1950 | 14,272 | 111.9% | |

| 1960 | 72,700 | 409.4% | |

| 1970 | 93,058 | 28.0% | |

| 1980 | 93,585 | 0.6% | |

| 1990 | 111,498 | 19.1% | |

| 2000 | 140,030 | 25.6% | |

| 2010 | 144,186 | 3.0% | |

| 2020 | 162,954 | 13.0% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 159,770 | [42] | −2.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[43] | |||

2020

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[44] | Pop 2010[45] | Pop 2020[46] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 40,896 | 27,178 | 21,436 | 29.21% | 18.85% | 13.15% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 14,846 | 16,297 | 14,003 | 10.60% | 11.30% | 8.59% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 570 | 492 | 346 | 0.41% | 0.34% | 0.21% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 26,189 | 31,090 | 47,655 | 18.70% | 21.56% | 29.24% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 2,511 | 4,290 | 4,915 | 1.79% | 2.98% | 3.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 692 | 352 | 913 | 0.49% | 0.24% | 0.56% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 6,476 | 5,757 | 6,607 | 4.62% | 3.99% | 4.05% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 47,850 | 58,730 | 67,079 | 34.17% | 40.73% | 41.16% |

| Total | 140,030 | 144,186 | 162,954 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census reported that Hayward had a population of 144,186.[47] The population density was 2,261.8 inhabitants per square mile (873.3/km2). The census determined racial and ethnic makeup of Hayward was 49,309 (34.2%) White, 17,099 (11.9%) African American, 1,396 (1.0%) Native American, 31,666 (22.0%) Asian (10.4% Filipino, 3.9% Chinese, 3.0% Indian, 2.7% Vietnamese, 0.5% Japanese, 0.5% Korean, 0.2% Cambodian, 0.1% Pakistani), 4,535 (3.1%) Pacific Islander, 30,004 (20.8%) from other races, and 10,177 (7.1%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 58,730 persons (40.7%), giving Hayward an aggregate Hispanic/Latino plurality population as categorized by census determined racial and ethnic groups. 30.2% of Hayward's population was Mexican, 2.5% Salvadoran, 1.5% Puerto Rican, 1.2% Nicaraguan, 1.0% Honduran, 0.5% Peruvian, and 0.2% Cuban.[48] Hayward is the second most diverse city in the state by Census figures.[49] It has been ranked nationwide as highly diverse, in combination with Oakland and Fremont.[50]

The Census reported that 141,462 people (98.1% of the population) lived in households, 1,954 (1.4%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 770 (0.5%) were institutionalized.[51]

There were 45,365 households, out of which 18,284 (40.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 21,720 (47.9%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 7,495 (16.5%) had a female householder with no husband present, 3,344 (7.4%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 3,037 (6.7%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 421 (0.9%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 9,359 households (20.6%) were made up of individuals, and 3,193 (7.0%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.12 persons. There were 32,559 families (71.8% of all households); the average family size was 3.60 persons.[52]

The city's age demographics were 35,379 people (24.5%) under the age of 18, 16,064 people (11.1%) aged 18 to 24, 44,005 people (30.5%) aged 25 to 44, 34,096 people (23.6%) aged 45 to 64, and 14,642 people (10.2%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33.5 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.7 males.[53]

There were 48,296 housing units at an average density of 757.6 units per square mile (292.5 units/km2), of which 45,365 were occupied, of which 23,935 (52.8%) were owner-occupied, and 21,430 (47.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.3%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.6%. About 75,039 people (52.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 66,423 people (46.1%) lived in rental housing units.[51]

2000

[edit]The 2000 Census reported there were 140,030 people, 44,804 households, and 31,945 families in the city.[54] The population density was 1,219.6/km2 (3,159/sq mi). There were 45,922 housing units at an average density of 400.0 units/km2 (1,036 units/sq mi). The racial and ethnic makeup of the city was 42.95% White, 10.98% Black or African American, 0.84% Native American, 18.98% Asian, 1.91% Pacific Islander, 16.81% from other races, and 7.52% from two or more races. 34.17% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 44,804 households, out of which 37.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.3% were married couples living together, 14.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.7% were non-families. 20.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.08 and the average family size was 3.58.

The population profiled by age was 26.8% under the age of 18, 10.9% from 18 to 24, 33.4% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $51,177, and the median income for a family was $54,712. Males had a median income of $37,711 versus $31,481 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,695. 10.0% of the population and 7.2% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 11.7% of those under the age of 18 and 7.2% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Government

[edit]

Hayward has a council–manager government. Hayward's mayor is Mark Salinas,[55] elected in November 2022.[55][56][57][58][59] City Council and other government meetings are cablecast on cable TV channel KHRT-TV.

The city received an "AA", and an "AA+" rating for its general obligations, from the Fitch Group in 2012.[60]

In July 2012, Hayward began working on an updated 25-year General Plan, which was adopted on July 1, 2014.[61] The city last updated their General Plan in 2002.

The Hayward Hall of Justice, a branch of the California Superior Court, is the largest full-service courthouse in Alameda County.[62]

Politics

[edit]According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Hayward has 70,194 registered voters. Of those, 39,327 (56%) are registered Democrats, 6,960 (9.9%) are registered Republicans, and 21,104 (30.1%) have declined to state a political party.[63]

Economy

[edit]Manufacturing

[edit]Hayward has a large number of manufacturing companies, both corporate headquarters and plants. This includes some high-tech companies, with Hayward considered part of a northern extension of Silicon Valley.[64] Manufacturing plants in Hayward include Annabelle Candy,[65] Columbus Salame,[66] the Shasta soft drink company, and a PepsiCo production and distribution center.[67]

Retail

[edit]Southland Mall is the largest shopping center in Hayward.

Former businesses

[edit]Hunt Brothers Cannery

[edit]The economy of Hayward in the first half of the twentieth century was based largely on the Hunt Brothers Cannery. The cannery was opened in Hayward in 1895 by brothers William and Joseph Hunt, who were fruit packers originally from Sebastopol, California.[68] The Hunts initially packed local fruit, including cherries, peaches, and apricots, then added tomatoes, which became the mainstay of their business. At its height in the 1960s and 1970s, Hunt's operated three canneries in Hayward, at A, B, and C Streets; an adjacent can-making company; a pickling factory; and a glass manufacturing plant. From the 1890s until its closure in 1981, Hunt's employed a large percentage of the local population. The air around Hayward was permeated by the smell of tomatoes for three months of each year, during the canning season. The canneries closed in 1981, as there were no longer enough produce fields or fruit orchards near the cannery to make it economically viable. Much of the production was moved to the Sacramento Valley. The location of the former canneries is marked by a historic water tower with the Hayward logo.[69] A housing development now occupies much of the former cannery site.[70]

Gillig Corporation

[edit]Gillig, a bus manufacturer, was located in Hayward for more than 80 years before moving to Livermore in 2017.[71]

Other former businesses

[edit]Much of the Bay coastal territory of Hayward was turned into salt ponds, with Oliver Salt and Leslie Salt operating there.[72][73] Much of this land has in recent years been returned to salt marshes. A 1983 image of the ponds appears on a 2012 U.S. postage stamp.[74] The Mervyns department store chain was headquartered in Hayward until it declared bankruptcy in 2008.

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[75] the top employers in the city were (in alphabetical order):

| Employer |

|---|

| Alameda County Sheriff's Department† |

| Baxter Bio Pharma |

| Berkeley Farms |

| California State University, East Bay† |

| Chabot College† |

| Fremont Bank |

| Hayward Unified School District |

| Illumina |

| Impax Laboratories |

| Pentagon Technologies |

| Plastikon Industries |

| Siemens Building Technologies |

| St. Rose Hospital† |

† indicates employers wholly located or headquartered in Hayward

Transportation

[edit]Freeways

[edit]

Hayward is served by Interstate 880 (also known as the Nimitz Freeway), Interstate 580 with a major intersection near downtown connecting State Route 238 and Interstate 238, State Route 92 (Jackson Street) and State Route 238 (Mission Boulevard/Foothill Boulevard). State Route 92 continues west as the San Mateo–Hayward Bridge. The intersection of 880 and 92 was reconstructed over a four-year period, with completion of the project in October 2011.[76][77] Mission Boulevard has been long known for chronic traffic congestion. Past proposals to convert Mission Boulevard to a freeway or build a 238 bypass have been controversial. One proposal, to build a freeway parallel to Mission Boulevard, extending a freeway south from 580 where it turns east towards Castro Valley, and connecting to Industrial Boulevard, had land purchased, but was cancelled in 2004 after years of debate.[78] The land is now scheduled for sale and zoning.[79]

Mission, Jackson, and Foothill all converge at one congested intersection south of downtown, known historically as "Five Flags" for a line of flagpoles located there. To alleviate congestion in the downtown area, the city has converted the A Street, Mission and Foothill triangle to one-way thoroughfares (counterclockwise), and is adding road improvements, landscaping, and telephone/cable undergrounding to Mission Boulevard south to Industrial Boulevard, and to Foothill Boulevard north to 580.[80] The plan, known as the Route 238 Corridor Improvement Project, broke ground July 2010, completed rerouting in 2013, and was completed in 2013.[81][82][83]

Public transit

[edit]Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), the regional rapid transit system, has two stations in Hayward: the Hayward station, in downtown; and the South Hayward station, near the Hayward–Union City border. BART operates a repair yard in Hayward.[84][85] The AC Transit bus system, which provides bus service for Alameda County and Contra Costa County, operates in Hayward, and has a repair/training center located there. Amtrak, the national rail passenger system, provides daily service at its Hayward station for the Capitol Corridor train, which runs between San Jose in the South Bay, and Auburn in the Greater Sacramento area.

Aviation

[edit]Hayward has a general aviation airport, the Hayward Executive Airport. The Hayward Air National Guard station was located at the airport in 1942, until being reassigned to Moffett Field in 1980.[86]

Infrastructure

[edit]Hayward maintains the Hayward Fire Department (with nine stations)[87] and the Hayward Police Department. Hayward has its own water and wastewater systems, but a small northern portion of the city's water is managed by the East Bay Municipal Utility District.[88] The Hayward Public Library opened at the intersection of C Street and Mission Boulevard in 1951. In 2013, plans were under development to construct a $60 million library across the street from the existing building, with funding uncertain.[89] Construction of the library began in 2016.[90]

Health care

[edit]Hayward has one hospital with emergency departments, St. Rose Hospital,[91] which was at risk of closure as of 2012.[92] A Kaiser Permanente Medical Center closed in 2014, replaced by a San Leandro hospital.[93][94][95] Horizon Services, which administers substance abuse recovery programs in Hayward and other locations in the Bay Area, operates out of Hayward, as does the Family Emergency Shelter Coalition. The Hayward Fire Department opened the Firehouse Clinic in November 2015, the first combined fire station/medical center in California.[96]

Cemeteries

[edit]Four cemeteries are located in Hayward: Chapel of the Chimes,[97] Mt. Eden Cemetery,[98] Mount Saint Joseph Cemetery,[99] and Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, the last two being Catholic cemeteries.[100]

Arts and culture

[edit]The city created the Hayward Public Art Program in 2008, to create murals to beautify the city and combat graffiti, and has commissioned numerous murals throughout the city.[101][102] The program won a League of California Cities Helen Putnam Award of Excellence in 2011.[103]

Hayward has been a Tree City USA since 1986.[104] Hayward declared itself a nuclear-free zone, a largely symbolic act, in 1987.[105] The city is the setting for the Hayward Gay Prom, one of the earliest and longest-running gay proms in the United States. The city introduced road signs in 2015 encouraging better behavior while walking or driving, using phrases like "It's a speed limit, not a suggestion".[106][107]

The slang term "Hella", which has spread globally, is said to have its roots in Hayward, tracing back to the 1970s.[108][109]

The new Hayward Library, officially known as the 21st Century Library and Community Learning Center, began construction following a groundbreaking ceremony on October 3, 2015.[110] The library opened to the public on September 14, 2019. This project was part of a broader initiative to create a new, modern community space while adhering to environmentally sustainable building practices, making it a net-zero energy facility

Downtown Hayward

[edit]Many of Hayward's cultural landmarks and points of interest are in its downtown area. Three city hall buildings have been built: Hayward City Hall; the City Center Building, an abandoned 11-story building and Hayward's second city hall; and the first city hall at Alex Giualini Plaza, whose architectural motifs form the current city logo.

Other downtown features include the Hayward Area Historical Society museum, which relocated and reopened in June 2014; Buffalo Bill's Brewery, one of the first brewpubs in California; Cinema Place, one Hayward's two movie theatre, with associated murals and an art gallery.[111] Many of the Hayward Public Art Program murals are located downtown.

Historic landmarks

[edit]Hayward has two sites in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP): the Green Shutter Hotel and Eden Congregational Church. A third site, Meek Mansion (also in the NRHP), while not within city limits, is managed by HARD and the Hayward Area Historical Society. The three sites are also on the California Register of Historical Resources.[112] Agapius Honcharenko's Ukraina Ranch is the only California Historical Landmark in the city.[113]

Parks and protected areas

[edit]Hayward has four parks administered by the East Bay Regional Park District: the Don Castro Regional Recreation Area, Dry Creek Pioneer Regional Park, the Hayward Regional Shoreline, and Garin Regional Park. The Eden Landing Ecological Reserve is located at the Hayward shoreline, and includes 600 acres (240 ha) of salt ponds set to be converted to tidal wetlands.[115] Hayward is also home to the oldest Japanese garden in California designed along traditional lines. The 3.5-acre (1.4 ha) Japanese Gardens was dedicated in 1980.[116] The garden is administered by the Hayward Area Recreation and Park District (HARD), which operates a number of parks and facilities, primarily in Hayward, including Kennedy Park, the Sulphur Creek Nature Center, the Hayward Shoreline Interpretive Center, and Memorial Park with the Hayward Plunge swim center.[117] HARD is the largest recreation district in California.[118]

Sports

[edit]The East Bay FC Stompers amateur soccer team is based in Hayward. The All Pro Wrestling professional wrestling promotion and training school is based in Hayward, and performs shows there.[119] Hayward was briefly considered for the new home of the New York Giants baseball team in 1957, with San Francisco acquiring the team.[citation needed]

The Hayward Area Recreation and Park District operates the Skywest and Mission Hills golf courses. In addition to the two public golf courses, TPC Stonebrae, a private golf club, operates in Hayward. It hosts the Ellie Mae Classic (formerly known as the TPC Stonebrae Championship), part of the Web.com Tour since 2009.[120]

Education

[edit]California State University, East Bay

[edit]

Hayward is home to the main campus of California State University, East Bay (CSUEB), formerly known as California State University, Hayward.[121] It is a public university within the California State University system. Pioneer Amphitheatre is located there, and is host to public music festivals.

Chabot College

[edit]Hayward is the home of Chabot College, a community college in the Chabot–Las Positas Community College District.[122]

Life Chiropractic College West

[edit]Life Chiropractic College is also situated in Hayward. Founded as Pacific States Chiropractic College in 1976, it is best known for its Doctor of Chiropractic program.

Primary and secondary schools

[edit]The majority of Hayward is served by the Hayward Unified School District (HUSD),[123] which operates three high schools, Mount Eden, Tennyson, and Hayward High, all three HUSD high schools in 2018 got new football fields along with new performing arts center and other new classroom wings are planned.

Small portions of Hayward are in the New Haven Unified School District, San Lorenzo Unified School District, Castro Valley Unified School District, and Pleasanton Unified School District.[123]

Additional high schools include the Eden Area Regional Occupational Program, the Leadership Public Schools, Hayward charter school (ranked #2 among charter schools statewide by a University of Southern California study)[124] and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation charter public high school, Impact Academy of Arts and Technology.[125] The New Haven Unified School District operates in Union City and South Hayward/Fairway park area with two schools, Conley–Caraballo and Hillview Crest Elementary. Most students in South Hayward also attend other New Haven schools and James Logan High school. The San Lorenzo Unified School District operates Royal Sunset High School within Hayward.[126] A large private high school, Moreau Catholic High School, is located in Hayward. Promise Neighborhood grant from the United States Department of Education, through CSUEB.[127][128][129]

Media

[edit]The East Bay Echo, which publishes regularly online and prints a monthly newspaper, offers local coverage.[130] Two newspapers of general circulation cover Hayward. From 1944 to 2016, Hayward ran a daily newspaper, the Daily Review, published most recently by Bay Area News Group. The Tri-City Voice newspaper, based in Fremont and published twice weekly, covers Hayward as well as the Tri-City area of Fremont, Newark, and Union City. It was founded in 2002.[131] The East Bay Express weekly newspaper, founded in 1978, covers Hayward as part of its East Bay coverage. Local television stations, and AM and FM radio from Oakland and San Francisco reach Hayward, as do some stations from San Jose, Sacramento, and Salinas. The city's cable TV carrier is Comcast. California State University, East Bay's student-run newspaper, The Pioneer, has covered the East Bay since 1961. Chabot College's student radio station, KCRH, operates mostly within city limits.

Notable people

[edit]People from Hayward who are strongly associated with the city include founder William Dutton Hayward[132] and the Ukrainian patriot and Greek Orthodox priest Agapius Honcharenko, who created a farm whose location is now an historic landmark.[133] High-profile people from Hayward include Los Angeles Sparks point guard Chelsea Gray,[134] football coach Bill Walsh,[135] former Oakland Raiders coach Jack Del Rio,[136] figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi,[137] two-time Oscar winner Mahershala Ali,[138] professional wrestler and actor Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson,[139] rapper Spice 1,[140] former Treasurer of the United States Rosa Gumataotao Rios[141] and rapper Saweetie. Charles Plummer,[142] prior to becoming Alameda County Sheriff, was the Police Chief of Hayward.

Sister cities

[edit]Hayward's five sister cities are:[143]

Faro, Portugal

Faro, Portugal Funabashi, Japan

Funabashi, Japan Ghazni, Afghanistan

Ghazni, Afghanistan San Felipe, Baja California, Mexico

San Felipe, Baja California, Mexico Yixing, China

Yixing, China

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "ACCESS HAYWARD". Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "Hayward". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. January 19, 1981. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Mayor & City Council - Welcome!". Archived from the original on October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Senators". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "California's 14th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Hayward". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Hayward city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ "ZIP Code(tm) Lookup". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ "COH_Budget_Back_Final.ai" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 1, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas – U.S. Census Bureau". Census.gov. February 8, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Gudde, Erwin G., "California Place Names" (4th Ed. 1998)

- ^ For example, see Kirkbride, Wayne, "Golden Dreams and the Success that Followed," Sierra Mountain Times, Retrieved on April 27, 2009; and GeoQuery: Places: USGS Geographic Name Information Server; TerraFly GeoQuery website, Retrieved on April 27, 2009

- ^ GNIS Detail – Hayward. Geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 641. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ^ Boehm, Evelyn (1975). Randall, Florence Carr (ed.). Hayward ... the First 100 Years. Hayward Centennials Committee. p. 9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marciel, Doris; Hayward Area Historical Society (2013). Legendary Locals of Castro Valley, Hayward, and San Lorenzo, California. Legendary Locals. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4671-0065-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hayward

- ^ Stanger, Frank M., ed. 1968. La Peninsula Vol. XIV No. 4, March 1968.

- ^ "Officially Designated Historic Buildings of Hayward". Hayward Area Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ "Mt. Eden Neighborhood Plan" (PDF). June 7, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "History of Hayward". Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Harry Rowell family website". Theharryrowellfamily.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Rowell Ranch at the Hayward Area Recreation and Parks Department website". Haywardrec.org. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ San Lorenzo Japanese Christian Church (February 22, 1999). "San Lorenzo Japanese Christian Church history". Slzjcc.org. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Site design and illustration by www.darriendesign.com (June 4, 1932). "Encyclopedia of San Francisco". Sfhistoryencyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Foothill Boulevard in Hayward undergoing transformation". Mercurynews.com. January 19, 2013.

- ^ Parr, Rebecca (May 16, 2015). "EPA chief leads dedication of Hayward solar landfill conversion". Contra Costa Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ "Hayward's 21st Century Library". Haywardfriends.org. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "Hayward breaks ground on new library, heritage plaza - City of Hayward - Official website". Hayward-ca.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "GNIS Account Login". geonames.usgs.gov.

- ^ Russell City Energy Center Amendment Proceeding Archived November 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Energy.ca.gov. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-NRG, Calpine adding natgas-fired plants in California". In.reuters.com. May 2, 2013. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ "The Telegraph - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Hayward, California 1911-2020 Normals". NOAA.

- ^ "Monthly Weather Information for Hayward". Weather.com.

- ^ "Sunshine info for Hayward/San Francisco Bay California". Usclimatedata.com.

- ^ "E-5 Population and Housing Estimates for Cities, Counties, and the State, 2020-2024". State of California Department of Finance. May 2024. Archived from the original on May 15, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Hayward city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Hayward city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Hayward city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Hayward city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". Census.gov. Retrieved August 27, 2011.

- ^ "Chavez Supermarket sets up shop on Mission Boulevard in Hayward". Inside Bay Area. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "News Headlines". CNBC. May 17, 2011. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ "U. S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "Mayor Mark Salinas | City of Hayward - Official website". www.hayward-ca.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Mayor & City Council – Welcome!". City of Hayward. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Fremont Bank Foundation Awards $100,000 Grant to Local Nonprofit". Newark, CA Patch. April 8, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "House Resolution No. 82--Relative to commending the Honorable Michael Sweeney". Leginfo.ca.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ "Halliday emerges as front-runner". Mercurynews.com. June 3, 2014.

- ^ "TEXT-Fitch affirms Hayward, Calif. COPs at 'AA'". In.reuters.com. August 7, 2012. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "How was the General Plan Prepared?". Hayward2040generalplan.com. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "Alameda County Courts website". Alameda.courts.ca.gov. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "The Northern Silicon Valley Partnership". Edab.org. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "company history at Annabelle Candy website". Annabelle-candy.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Two years after facility burned down, new salami plant opens in Hayward". Inside Bay Area. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Corinne DeBra (June 28, 2011). "Walking San Francisco Bay: Hesperian Blvd. – June 20, 2011". Walkingthebay.blogspot.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Hunt's corporate website". Hunts.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived July 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Housing OK'd for Hayward cannery site". Oakland Tribune, The. December 21, 2001.

- ^ Ruggiero, Angela (May 19, 2017). "Final day in Hayward as bus manufacturing titan Gillig heads to Livermore". East Bay Times. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ "History – Biographies, Landmarks, Patents". ASME. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "Salt Photos – Collection » Hayward Area Historical Society". Haywardareahistory.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "Hayward photo by Berkeley photographer chosen for stamp". Inside Bay Area. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "CITY OF HAYWARD, CALIFORNIA COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2015" (PDF). Hayward-ca.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 21, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ^ Eric KurhiOakland Tribune (October 7, 2011). "At long last, improved connectors open at Hayward traffic trouble spot – San Jose Mercury News". Mercurynews.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ SR-92/I-880 Interchange Reconstruction Project Archived August 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. I880corridor.com (August 16, 2010). Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Hayward cottages now owned by Caltrans considered for historical designation". ContraCostaTimes.com. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ District 4 | State Route 238 Hayward Bypass Program. Dot.ca.gov. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Hayward to begin one-way downtown traffic loop March 15". Mercurynews.com. February 19, 2013.

- ^ Route 238 Corridor Improvement Project. Council Work Session Archived July 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Hayward-ca.gov, January 20, 2009

- ^ "Foothill Boulevard gateway getting face-lift in Hayward". Inside Bay Area. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ ""Loop" construction through downtown Hayward". Photos.mercurynews.com. July 31, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "Santa Clara VTA receives state funding to expand BART facilities", RT&S, December 7, 2012

- ^ "Hayward Maintenance Complex". Bart.gov.

- ^ "Hayward Air National Guard Base". Militarymuseum.org. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Fire Department - Welcome!". Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "EBMUD ward map, EBMUD website". Ebmud.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Parr, Rebecca; Matthew Artz; Ashly McGlone. Hayward short on cash for new library. The Oakland Tribune. July 20, 2013.

- ^ "Hayward's 21st Century Library and Heritage Plaza". Haywardlibrary.org.

- ^ St. Rose Hospital website. St. Rose Hospital. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "St. Rose Transition Authority holds first meeting in quest to save Hayward hospital – San Jose Mercury News". Mercurynews.com. August 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Replogle, Jill (July 8, 2011). "Kaiser's San Leandro Medical Center Hits Its High Mark – San Leandro, CA Patch". Sanleandro.patch.com. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "Kaiser slows preparation for San Leandro hospital". Bizjournals.com. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Hayward Medical Center – Services and Locations – Kaiser Permanente Archived July 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Members.kaiserpermanente.org. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Hayward first California city to put fire station, medical center together". Sfgate.com. November 14, 2015.

- ^ "Chapel of the Chimes Hayward". Chapelofthechimes.com.

- ^ Mt. Eden Cemetery – Alameda County, California. Interment.net. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ Alameda County Databases Cemeteries. SFgenealogy. Retrieved on March 5, 2022.

- ^ Bay Area, California | Catholic Funeral and Cemetery Services – Holy Angels Holy Sepulchre – Hayward Archived January 26, 2011, at archive.today. CFCS Cemeteries. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Hayward Mural Art Program Combats Graffiti". The Pioneer Online. July 27, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "Murals that adorn Hayward walls also fight graffiti", San Jose Mercury News, February 10, 2013

- ^ "Helen Putnam Award of Excellence". Helenputnam.org. April 12, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "Tree Cities at". Arborday.org. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Ordinance No. 87-024, An Ordinance Establishing Nuclear Free Hayward Archived December 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Snarky California road signs aim to change behavior". Cbsnews.com. February 12, 2015.

- ^ "Street Sign Says 'Cross the Street, Then Update Facebook'". Popularmechanics.com. February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Hyphy a Guide to Bay Area Slang". kswb.com. March 24, 2016.

- ^ "Northern California Slang "Hella" Added to Merriam Webster New Edition". patch.com. April 22, 2016.

- ^ "Hayward Library Groundbreaking".

- ^ "Blake Hunt Ventures, Inc". Blakehunt.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Historic Resources Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Ohp.parks.ca.gov. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ OHP Listed Resources. Ohp.parks.ca.gov. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Portuguese Centennial Park – Hayward, CA – Municipal Parks and Plazas on". Waymarking.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Eden Landing Salt Pond Restoration Project, at the Save The Bay website". Savesfbay.org. April 21, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ The Japanese Gardens Archived August 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Dmtonline.org. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ Hayward Area Recreation and Park District Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Haywardrec.org. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ Hayward Area Recreation and Park District. Haywardrec.org. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "jonathan". Allprowrestling.com. October 24, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "PGA golf returns to the Hayward Hills". Sfgate.com. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ It's Official: CSU Trustees Vote Unanimously To Change University Name to 'Cal State East Bay' Archived June 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Calstate.edu (January 26, 2005). Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Chabot-Las Positas Community College District website". Clpccd.cc.ca.us. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Alameda County, CA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "USC Report Names Top 10 California Charter Schools". Newswise.com. June 19, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ Impact Academy of Arts and Technology : Contact Us Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Es-impact.org. Retrieved on December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Royal Sunset High School: Home Page". Rshs-slzusd-ca.schoolloop.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Hayward Promise neighborhood kick-off event", San Jose Mercury News, Oct 27, 2012

- ^ "Hayward Promise Neighborhood". Hayward-ca.gov. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Education Awards Promise Neighborhoods Planning Grants | U.S. Department of Education". Ed.gov. September 21, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ https://eastbayecho.com/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Tri-City Voice Newspaper – Whats Happening – Fremont, Union City, Newark, California". Tricityvoice.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "William Hayward". Hayward Area Historical Society. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Agapius Honcharenko". Hayward Area Historical Society. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Ingemi, Marisa (July 18, 2023). "Year after snub, Bay Area's Chelsea Gray one of WNBA's biggest stars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Tom (November 12, 2007). "Former 49er head coach Bill Walsh dies". Sfgate. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Tafur, Vic (January 24, 2015). "Raiders head coach Jack Del Rio still hero in Hayward". SFGATE. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Kristi Yamaguchi-Kristi Yamaguchi is a U.S. figure skater and Olympic gold medalist. She is also an author, philanthropist and founder of the Always Dream Foundation". Biography. April 15, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Mahershala Ali ('96)". March 2, 2019. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Barney, Chuck (January 27, 2021). "Sorry, Hayward, Johnson's TV show skips his time in the Bay Area". The Mercury News. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Sweeney, Jason (December 8, 2007). "Rapper Spice 1 describes shooting from hospital bed". East Bay Times. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ "Key to city to Rosie Rios". www.hayward-ca.gov. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Kelly, George (March 6, 2018). "Charles Plummer, former Alameda County sheriff, dies at 87". East Bay Times. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "By the Numbers". City of Hayward. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- map of Alameda County, showing Hayward's borders (Alameda County website)