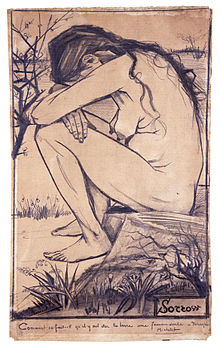

Impact of prostitution on mental health

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (June 2024) |

The Impact of prostitution on mental health refers to the psychological, cognitive, and emotional consequences experienced by individuals involved in prostitution. These consequences include a wide range of mental health issues and difficulties in emotional management and interpersonal relationships. Prostitution is closely linked to various psychological pathologies and affects not only those directly involved but also society at large. Studies have shown that both street and indoor sex workers have experienced high levels of abuse in childhood and adulthood, with differences in trauma rates between the two groups.

Women in prostitution experience a profound impact on their identity, encompassing cognitive, physical, and emotional dimensions, manifesting in health problems and difficulties in emotional management and interpersonal relationships.[1] Prostitution, being strongly linked to psychopathology and social health, should be addressed as a medical situation that affects not only the individuals involved but also society at large, with psychological aspects.[2]

Sex work involves the provision of one or more sexual services in exchange for money or goods. However, sex workers are not a homogeneous group. Street sex workers are often illegal, finding clients on the street and providing services in alleys or clients' cars. On the other hand, indoor sex workers operate in brothels, massage parlors, or as private escorts. Previous research has shown that both street and indoor sex workers have experienced high levels of abuse in childhood and adulthood, though indoor sex workers report lower rates of abuse and trauma compared to street workers.[3]

There is a high prevalence of victimization in childhood and adulthood among sex workers, with secondary trauma disorders. Recurrent victimization, known as "Type II trauma," can cause pathological psychological changes that are difficult to classify. Proposed diagnoses include developmental trauma disorder for childhood and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD) for adulthood, though these are not included in official diagnostic manuals.[4]

There is a connection between prostitution and trafficking, organized crimes that reflect sexism, patriarchy, capitalism, and economic inequality. The physical consequences of sexual exploitation include sexually transmitted diseases, cervical cancer, chronic pain, liver problems, unintended pregnancies, eating disorders, concentration and memory difficulties, visual and hearing problems, fractures, and, in extreme cases, death. Psychologically, women suffer from low self-esteem, stress, pathological ties with control networks, social isolation, loneliness, extreme fear, hopelessness, and a lack of assertiveness in seeking support, resulting in trauma that alters their beliefs and perceptions, causing irreparable damage to their personal identity. These conditions are exacerbated by language barriers and other vulnerability factors, such as having suffered sexual abuse in childhood or being the main economic support for their family, which is exploited by pimps.[1]

The effects on mental health are severe, with high rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among those who sell sex, exacerbated by social stigma, discrimination, physical violence, and mistreatment by authorities. Studies in the United States and Canada reveal depression symptoms in 68% of these individuals and PTSD symptoms in nearly a third, showing higher rates than in combat veterans. Substance abuse is common, generally as a response to sex work rather than a cause, with most increasing drug use to cope with their reality.[5]

The sex industry is a global business worth $57 billion annually, with the United States hosting the largest number of adult clubs in the world, employing over 500,000 people. Between 66% and 90% of women in this industry were sexually abused during their childhood. These women have higher rates of substance abuse, sexually transmitted infections, domestic violence, depression, violent aggression, rape, and PTSD compared to the general population.[6]

The emotional effects of prostitution are devastating. Dissociation, a response to uncontrollable traumatic events, is common among prostituted individuals, similar to the response of prisoners of war. Research has shown that both indoor and outdoor sex work increase the risk of being assaulted. In outdoor sex work 82% of women reported being physically assaulted, and 68% reported being raped. In indoor settings, more sexual violence and threats with weapons were reported. Women in the sex industry frequently face multiple psychosocial stressors, limited resources, and a high rate of untreated health and legal problems.[6]

Other studies that assessed the presence of psychological alterations in prostitutes, compared to non-prostitutes, also documented concentration and memory difficulties, as well as sleep problems (with an incidence of 79%), irritability (64%), anxiety (60%), phobias (26%), panic attacks (24%), compulsions (37%), obsessions (53%), fatigue (82%), and concerns about physical health (35%), and 30% of the sample reported a suicide attempt.[7]

Context

[edit]

The consequences of being repeatedly bought and sold for sex with strangers result in a variety of medical issues, including malnutrition, pregnancy-related problems, old and new injuries from sexual assaults and physical attacks such as burns, broken bones, stab wounds, dental trauma, traumatic brain injuries, anogenital injuries (rectal prolapse/vaginal injuries), internal injuries, sexually transmitted infections, and untreated chronic medical conditions.[9] Individuals in prostitution are subjected to multiple forms of violence, such as rape, sexual assault, emotional abuse, economic and physical abuse, food deprivation and sleep deprivation, and acts of torture by pimps, traffickers, brothel owners, and sex buyers.[10] This results in cumulative psychological and physical trauma with lifelong impacts.[11] Individuals in prostitution often experience stress and multiple traumas, such as physical or sexual abuse in childhood, the sexual exploitation itself, and homelessness, and may have difficulty remembering details of their lives due to traumatic brain injuries, cognitive impairment, repressed memories, or dissociation, largely caused by pimps, traffickers, and sex buyers. Reported psychiatric disorders include depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, eating disorders, sexual dysfunction, substance abuse, suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, self-harm, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and dissociative disorders.[11]

Dissociation, a severe symptom related to trauma, is common and develops as a coping strategy in response to extremely painful, frightening, or potentially life-threatening events.[12] Additionally, pimps and traffickers often control victims' access to medical care, allowing them to seek help only when injuries or illnesses are particularly severe or if their ability to earn money is affected, but often prohibiting preventive or follow-up care. The traumatic scars from this physical and psychological damage are permanent. Children trafficked for sex are the most vulnerable to medical and psychological harm. Entry into prostitution typically occurs during childhood and adolescence, with most initially lured by a "boyfriend" and/or "protector." While not all enter the sex trade through a pimp or trafficker, each encounter with a sex buyer puts the individual at risk of harm.[13] Studies suggest that up to 50% of human trafficking victims seek medical care while in trafficking situations. The harmful effects of prostitution are reflected in the high rates of PTSD among survivors, with symptoms such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, irritability, recurrent memories, emotional numbness, and hypervigilance.[14] Of 475 individuals in prostitution interviewed in five countries, 67% met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, indicating that the traumatic consequences of prostitution are similar across cultures. Individuals in prostitution suffer extremely high levels of violence: 62% of women report being raped and 73% report being physically assaulted in the sex trade. Transgender youth in prostitution are over four times more likely to have HIV than those without such a history. The mortality rates for women in prostitution are 40 to 50 times the national average. Among known victims of fatal violence against transgender individuals in the U.S. from 2013 to 2018, 32% were in the sex trade, including many who died while in prostitution.[14]

In "Prostitution and the Invisibility of Harm," Melissa Farley examines how the harms associated with prostitution are invisible in society, law, public health, and psychology. Farley argues that the invisibility of these harms originates from the use of terms that conceal the inherent violence of prostitution, as well as from public health perspectives and psychological theories that ignore the harm inflicted by men on women in prostitution.[15] The author summarizes literature documenting the overwhelming physical and psychological harms suffered by individuals in prostitution and discusses the interconnection of prostitution with racism, colonialism, and child sexual abuse. Farley describes prostitution as a form of sexual violence that generates economic benefits for perpetrators and argues that, like slavery, it is a lucrative form of oppression. She highlights how institutions protect the commercial sex industry due to its enormous profits, and how these institutions, deeply rooted in cultures, become invisible. The author criticizes the normalization of prostitution by researchers, public health agencies, and the law, pointing out the contradiction in opposing human trafficking while promoting "consensual sex work." Farley argues that assuming consent in prostitution erases its harm and mentions that the line between coercion and consent in prostitution is deliberately blurred. The author proposes using terms that maintain the dignity of women in prostitution and criticizes the use of terms that disguise the inherent violence of this practice.[15] Furthermore, the article documents the prevalence of physical and sexual violence in prostitution, citing studies showing high percentages of rape and physical assault among women in this situation. Farley also highlights the similarity between domestic violence and violence in prostitution, suggesting that treatment approaches for battered women are also applicable to prostituted women. Finally, Farley addresses the intersection of racism and colonialism in prostitution, pointing out how women are exploited based on their appearance and ethnic stereotypes, and discusses how child sexual abuse sets the stage for prostitution in adolescence and adulthood.[15]

Source: Posttraumatic stress disorder among female street-based sex workers in the greater Sydney area, Australia.[16]

Research on the psychological impact associated with sex work, especially when exposed to violent situations, has shown that this activity is linked to the development of psychological stress and many other negative consequences in the short, medium, and long term. These consequences include depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, sexual trauma symptoms, and addiction disorders related to substance use.[7]

The study by El-Bassel et al. (1997) showed that sex workers, compared to a control sample, had higher scores on the subscales of obsessive–compulsive symptomatology, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. To assess whether there was a direct relationship, the authors isolated other variables that could contribute to these higher values (differences in age, ethnicity, pregnancy, perceived risk of contracting HIV, rape, and substance use) and found a significant correlation between sex work and psychological stress.[7]

In recent decades, the perception of mental health has changed significantly, especially among young people, who openly discuss depression, anxiety, and therapy. Mental health has become a recurring topic in popular culture, frequently featured in TV shows, movies, and songs, and has been the focus of numerous recently proposed and passed laws.[5] This change is crucial to addressing the mental health of high-risk groups, such as people who sell sex. These individuals, often forced into this activity by survival, coercion, or deception, usually lack support networks and face economic precariousness, prior violence, and social marginalization, with a particular risk for LGBTQ+ and Black girls. Most who have sold sex started as minors, wanted to leave the sex trade, and suffered significant harm, as recounted by Esperanza Fonseca, a survivor who describes feelings of loneliness and deep sadness.[5]

Prostitution can have profound and lasting psychological effects on those who engage in it. These effects can manifest in various disorders and symptoms that impact mental health and emotional well-being. Below is a detailed table exploring different psychological disorders associated with prostitution, describing their symptoms, reasons for occurrence, possible consequences, available treatments, severity, and prevalence among affected women.

| Disorder | Description and Symptoms | Reason for Occurrence | Consequences | Treatment | Severity | Percentage of Women Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of traumatic memories | Exposure to recurrent traumatic situations | Chronic anxiety, relationship problems, depression | Cognitive-behavioral therapy, EMDR, medication | High | 60% |

| Dissociative identity disorder | Multiple identities, amnesia, depersonalization | Severe trauma, need for emotional disconnection | Relationship difficulties, confusion, distress | Psychotherapy, integration techniques | High | 30% |

| Substance abuse | Excessive use of drugs or alcohol | Self-medication, escape from reality | Health problems, dependency, social deterioration | Rehabilitation, addiction therapy | High | 70% |

| Self-destructive behaviors | Self-harm, risky behaviors | Hopelessness, attempt to control emotional pain | Physical injuries, suicide attempts | Dialectical behavior therapy, psychological support | High | 40% |

| Depression | Persistent sadness, lack of interest, fatigue | Emotional and physical abuse, isolation | Decreased quality of life, suicidal ideation | Antidepressants, therapy | High | 65% |

| Constant sense of danger, extreme distrust of others | Continuous fear, avoidance of social interaction | Repeated traumas, betrayals | Isolation, relationship problems | Cognitive-behavioral therapy | High | 50% |

| Low self-esteem | Feeling of worthlessness, lack of confidence | Abuse and stigmatization | Self-sabotage, emotional dependency | Self-esteem therapy, positive affirmations | High | 70% |

| Anxiety | Nervousness, panic, restlessness | Constant stress, job insecurity | Sleep problems, digestive issues | Cognitive-behavioral therapy, medication | Medium | 55% |

| Hypervigilance and paranoia | Constant state of alertness, distrust | Exposure to dangerous situations | Fatigue, relationship problems | Therapy, relaxation techniques | Medium | 45% |

| Addiction to money, sex, and emotions | Compulsion to obtain money, sex, or intense emotional situations | Positive reinforcement of behaviors, need for validation | Financial problems, dysfunctional relationships | Therapy, support groups | Medium | 50% |

| Somatization | Physical pain with no apparent medical cause | Stress and emotional trauma | Medical problems, complicated diagnosis | Psychosomatic therapy | Medium | 35% |

| Memory problems | Frequent forgetfulness, confusion | Post-traumatic stress, dissociation | Difficulties in daily life | Cognitive therapy | Medium | 30% |

| Difficulties forming emotional bonds | Inability to trust or connect emotionally | Relational trauma, abandonment | Superficial relationships, loneliness | Bonding therapy | High | 50% |

| Loss of sexual pleasure | Sexual anhedonia, sexual dysfunction | Sexual trauma, abuse | Relationship problems, personal dissatisfaction | Sexual therapy, psychological support | High | 40% |

| Social isolation | Avoidance of social contact, loneliness | Shame, fear of judgment | Depression, anxiety | Group therapy, community support | High | 60% |

| Cognitive impairment | Concentration problems, decision-making difficulties | Prolonged trauma, stress | Work and personal difficulties | Cognitive therapy, brain training | Medium | 25% |

| Eating disorders | Bulimia, anorexia, compulsive eating | Stress control, distorted body image | Health problems, nutritional imbalance | Eating disorder therapy, nutritional support | High | 35% |

| Sleep disorders | Insomnia, nightmares | Stress, anxiety, trauma | Fatigue, mental health problems | Sleep therapy, sleep hygiene | Medium | 50% |

| Depersonalization and derealization | Persistent feelings of being outside one's body or that the surroundings are not real | Severe stress, dissociation as a defense mechanism | Difficulties functioning in daily life, isolation | Cognitive-behavioral therapy, grounding techniques | Medium | 20% |

Motivations for entering prostitution

[edit]«Generally here, they are all mothers and fathers of families, right? So, they are mothers by day and fathers by night, so it is difficult to save, right? Those clients are the ones who save us, right? They want fun, and we want money, right? That's all too.»

The study titled "Prostituição: um estudo sobre as dimensões de sofrimento psíquico entre as profissionais e seu trabalho" investigates the psychological difficulties that sex workers face due to moral judgments and adverse working conditions.[18] It is based on the psychodynamic approach to work, which defines normality as a precarious balance between work constraints and the psychological defenses workers develop to maintain their mental health. Prostitutes can preserve a psychological balance despite the constraints and moral judgments they face in contemporary society.[18] One of the research questions was why women choose prostitution as a profession.[18] The answers indicated that economic necessity is the most important factor. The workers mentioned the need to support their children and families as the main motivations for entering prostitution. Additionally, some compared their earnings in prostitution with previous jobs where they earned much less for longer and more difficult working hours.[18]

Sex workers develop mechanisms to manage their clients' desires and tastes, demonstrating their capacity for conception within their profession. However, they set clear boundaries on what they are willing to do, regardless of payment, to preserve their integrity and mental health.[18]

Most research points to financial and social problems as the main causes of prostitution. Factors such as lack of job opportunities, family conflicts, and urgent economic needs drive many women into this profession.[19] However, while the patriarchal system and gender violence are realities, there are also women who choose this profession by their own desires and will. Prostitution is not homogeneous and encompasses a plurality of desires and expressions of sexuality.[19]

Many women enter sex work through false promises of marriage or well-paid employment in another city. Once in sex work, perceived stigma and sexual abuse by law enforcement officers, who often are also clients, convince them that no external help is available.[20] These extreme circumstances force women to focus on survival rather than escape, which is essentially the core of Stockholm syndrome: a psychological attempt to survive physically in captivity. This behavior pattern is not limited to prostitution in brothels, as similar relationships are present in street, home-based, and caste-based prostitution. This has been a point of difficulty for rehabilitation programs against trafficking worldwide.[20]

The role of motherhood affects the decisions and behaviors of women trapped in these situations. Motherhood becomes not only a natural and biological role but also a source of vulnerability and emotional strength.[21] From a psychological perspective, the fear of losing their children or being unable to care for them adequately due to their sexual exploitation is one of the most influential factors in these women's psyches. This fear can generate intense anxiety and chronic stress, which in turn perpetuates the cycle of exploitation. The constant threat of separation from their children can trigger submissive and compliant responses, as women may feel trapped and without options. Anxiety and fear of abandonment not only affect their emotional well-being but also limit their ability to make rational and strategic decisions to escape their situation.[21]

The need to protect and support their children can conflict with their desire to escape and seek a better life. This cognitive dissonance can be debilitating, as women may feel constantly torn between two equally painful options.[21] The maternal instinct to protect their children can also motivate some women to seek escape from exploitation. But this protective drive may be hindered by the lack of resources, support, and viable options. Uncertainty about the future and fear of violent reprisals can paralyze their ability to act. From a psychological perspective, this can generate a state of learned helplessness, where women believe they have no control over their situation and that any attempt to change it will be futile or dangerous.[21]

Risk factors

[edit]«One night, my monthly bills were soon due, I had no gas in my vehicle, I had maxed out my credit cards, and I had no food in my fridge. In nothing but an act of total brokenness and desperation, I contacted a brother and inquired about employment.»

Prostitution is primarily associated with poverty and, in most cases, is not a professional choice or vocation, but a way of monetizing the body due to lack of opportunities. It is directly related to social inequality and gender issues in the country. The main beneficiaries of this trade are pimps and those involved in managing trafficking and sex tourism.[23]

Prostitution is often understood in the context of the traditional consumer risk model, where the consumed product is perceived as the agent carrying risks. However, in prostitution, the prostituted person is the "product" consumed, and it is they who are at greater risk, even though prostitution is sometimes erroneously described as "sex between consenting adults."[24] Prostitution occurs because the prostituted person would not consent to sex with the buyer if they were not paid, which redefines the notion of consent and risk in this context.[24] The traditional consumer risk model does not adequately apply to prostitution, where the prostituted person assumes significantly greater risks than the sex buyer or the pimp. A sex buyer interviewed explained that "being with a prostitute is like having a cup of coffee, when you finish, you throw it away." This perspective shows the dehumanization and objectification of prostituted individuals.[24]

Prostitution is often the result of a combination of individual, social, and economic factors. Individuals who engage in prostitution do so due to a series of adverse circumstances that limit their options and increase their vulnerability to exploitation. Below is a list of risk factors that can contribute to a person falling into prostitution:

- Poverty: The lack of economic resources is one of the main factors driving people to prostitution. The urgent need for money to cover basic necessities like food, housing, and medical care can lead to desperate decisions.

- Lack of education: Limited educational opportunities restrict employment options, which in turn can push individuals toward prostitution as a way to earn money quickly.

- Unemployment: The lack of employment or job instability can lead people to seek alternative means of income, including prostitution, especially in contexts where there are few formal job opportunities.

- History of childhood sexual abuse: Sexual abuse during childhood is a common precursor to prostitution. Traumatic experiences can lead to vulnerability and the normalization of sexual exploitation in adulthood.

- Domestic violence: Individuals who have been victims of domestic violence may turn to prostitution as a way to escape an abusive situation or to gain financial independence.

- Lack of family and social support: The absence of a strong support network can leave individuals without emotional or financial resources, increasing their vulnerability to sexual exploitation.

- Mental disorders: Mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder can make individuals more susceptible to exploitation in prostitution.

- Previous experiences of exploitation: Individuals who have been trafficked or exploited for labor may be more vulnerable to falling into prostitution due to the continuation of the exploitation cycle.

- Gender inequality: Discrimination and gender inequality can limit opportunities and increase women's vulnerability to sexual exploitation.

- Displacement and migration: Displaced or migrant individuals, especially those without documentation, are particularly vulnerable to sexual exploitation due to their precarious situation and lack of legal protection.

- Cultural and social factors: In some cultures and societies, social norms and expectations can contribute to sexual exploitation, either by stigmatizing victims or accepting prostitution as an economic solution.

- Coercion and deception: Many individuals are forced or deceived into prostitution, either through human trafficking, false promises of employment, or direct coercion by pimps.

Source: Psychosocial changes in the image of women engaged in prostitution[25]

The risks associated with prostitution are numerous and well-documented. They include sexual harassment, rape and unprotected rape, domestic violence, physical assault, and psychological aftermaths such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative disorders, depression, eating disorders, suicide attempts, and substance abuse. The frequency of rape in prostitution results in extremely high rates of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, with studies reporting an HIV prevalence of 93% in some prostituted populations. Family abuse and neglect often precede entry into prostitution. Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse during childhood is a common precursor, considered by many experts to be a necessary risk factor for prostitution. In one study, 70% of adult women in prostitution reported that childhood sexual abuse was responsible for their entry into prostitution. This abuse creates a cycle of victimization that impacts their futures and prepares them for exploitation in prostitution.[24]

The fantasies of sex buyers drive the realities of prostituted individuals. Buyers seek to fulfill their fantasies through prostituted individuals, who must act according to the buyer's expectations.[24] Failure to meet these expectations often leads to brutal violence. Objectification and dehumanization are intrinsic to prostitution, where prostituted individuals are seen as objects or products with economic value, facilitating their exploitation and abuse. Physical violence is a constant in prostitution.[24] An occupational study noted that 99% of women in prostitution were victims of violence, with more frequent injuries than in occupations considered dangerous such as mining or firefighting.[24] Poverty and duration in prostitution are associated with greater violence. In Vancouver, 75% of women in prostitution suffered physical injuries from violence, including fractures and head injuries.[24]

The emotional effects of prostitution are devastating. Dissociation, a response to uncontrollable traumatic events, is common among prostituted individuals, similar to the response of tortured prisoners of war or sexually abused children. Dissociation is a necessary skill for surviving rape in prostitution, reflecting the dissociation needed to endure family sexual abuse.[24] Dissociative disorders, depression, and other mood disorders are common among prostituted individuals in various settings.[24] Prostitution and slavery share characteristics of dehumanization and objectification, resulting in a "social death." The prostituted individual is reduced to body parts and acts out the roles desired by buyers, suffering a systematic assault on their humanity. This objectification becomes internalized, causing profound changes in their self-perception and their relationships with others.[24]

Sex buyers often understand the risks and consequences of prostitution but rationalize their behavior. Many acknowledge exploitation and economic coercion but continue to buy sex. Risk denial strategies, such as minimizing abuse or justifying payment, perpetuate exploitation.

Prostitution not only involves risks for prostituted individuals but also for buyers, who face legal risks, social stigma, and health risks. However, public attention often focuses more on the buyer's health than on the prostituted individual's, perpetuating the myth that prostituted individuals are vectors of disease.[24] Public denial of prostitution risks is fueled by narratives from buyers and pimps that conceal violence and exploitation. This denial is similar to strategies used by the tobacco industry or climate change deniers, where harms are minimized, and exploitation is justified.[24]

Government complicity sustains prostitution. The legalization and decriminalization of prostitution integrate this exploitation into the state economy, relieving governments of the responsibility to find employment for women. However, legalization does not eliminate the inherent risks of prostitution, as demonstrated by the recommendation for hostage negotiation training for those in legalized prostitution in Australia.[24] Harm reduction approaches in prostitution, such as distributing condoms, do not address the root causes of the problem.[24] Eliminating risk requires real survival options outside prostitution and a change in power structures that perpetuate exploitation. Survivor voices who have exited prostitution point toward obvious legal solutions. Sex buyers and pimps must be held accountable, and survival alternatives must be offered to prostituted individuals without criminalizing them. Several countries have adopted abolitionist approaches, penalizing sex buyers and providing exit services and job training for prostituted individuals.[24]

Types of prostitutes

[edit]

«There were 30 to 40 clients per day, men and women. My body endured 12-hour work shifts, and weekends lasted even longer. I needed painkillers to cope. From the first time, you become dead inside, different men touch you, and underage girls like me are fresh meat. They insulted me, hit me, spat on me, didn't respect me, and days, weeks, months passed like that... until it became four years.»

From a psychological perspective, prostitution presents a series of significant impacts that vary according to the type of sex work and the conditions under which it is carried out. Independent prostitutes, such as escorts and call girls, may experience lower levels of exploitation and have greater control over their working conditions, potentially mitigating some negative effects on their psychological well-being. However, those working under conditions of high exploitation and violence, such as street prostitutes or those held in debt bondage, face severe psychological consequences. These include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems due to physical, sexual, and emotional violence they suffer. Debt bondage, in particular, is an extreme form of exploitation where women are kept in conditions of slavery due to unpayable debts, prevalent in underdeveloped countries. This situation subjects them to severe trauma and a constant threat of violence, exacerbating their psychological problems and making it difficult to escape this cycle of abuse and exploitation.[27]

Street sex work, in particular, is associated with higher levels of stress and risk due to exposure to violence, third-party exploitation, and poor working conditions. Many street workers report experiences of physical and emotional abuse by both clients and pimps. This environment can lead to a higher incidence of mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[28]

On the other hand, sex workers operating in more controlled environments, such as escort agencies or brothels, report higher levels of job satisfaction and self-esteem. These workers have more control over their working conditions, can select their clients, and generally experience less violence. This greater autonomy and control can translate into better mental health and a greater sense of empowerment.[28]

| Type of Prostitute | Description | Detailed Psychological Impacts | Differences from Other Types of Prostitutes | Level of Violence | Clients per Day (Average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street Prostitute | Work on the streets, earn less, and are more vulnerable | High exploitation, less job satisfaction, high risk of violence | Lower income, higher risk of violence and exploitation | Very high | 8–12 |

| Debt-Bonded Prostitute | Held in establishments under an unpayable debt, common in underdeveloped countries | High exploitation, severe psychological trauma, physical and sexual violence | Forced to work indefinitely, inhumane conditions | Very high | 10–40 |

| Window Worker | Work in brothels with windows, like in Amsterdam, earn low to moderate wages | Social isolation, less job satisfaction | Visible to the public, less social contact than in brothels | Moderate | 5–15 |

| Bar or Casino Worker | Contact clients in bars or casinos and move to another location for the service | Low to moderate exploitation, potential dependence on regular clients | Variable income, greater geographical mobility | Moderate | 3–8 |

| Brothel Employee | Work in legal brothels, must share earnings with owners | Moderate exploitation, regular social contact with other workers | Fixed locations, more dynamic social environment | Moderate | 5–10 |

| Escort Agency Employee | Work in private locations or hotels, charge high prices, must share earnings with the agency | Moderate exploitation, some dependence on the agency | Similar to independents, but with less control over their earnings | Moderate | 2–4 |

| Independent Call Girl/Escort | Work independently in hotels and homes, charge high prices and maintain privacy | Less exploitation, more control over work conditions | Retain all their earnings, not dependent on third parties | Low | 1–3 |

| Source: Ronald Weitzer, "Legalizing Prostitution"[27][26] | |||||

High-end prostitutes

[edit]

In 1958, the study of the psychology of high-end prostitutes revealed a series of common patterns and traumas that shaped their behavior and life choices. Many of these women came from difficult childhoods, marked by broken homes and dysfunctional family relationships, contributing to their sense of insecurity and low self-esteem. From an early age, they learned to see sex as a currency, a means to obtain the emotional contact and tangible rewards they craved.[29]

These women, despite their superior intelligence and artistic abilities, felt emotionally adrift and lacked a clear concept of their feminine role. Their adult lives were marked by a constant search for validation and security, though paradoxically, they were trapped in a profession that perpetuated their feelings of worthlessness and anxiety. Most struggled with addiction problems and unstable relationships, unable to maintain solid friendships and resorting to psychological defenses such as projection and denial to cope with their reality.[29]

Financial success and outward luxury failed to mask their deep emotional distress. Often, they feigned joy and affection toward their clients, but in their private lives, many were unable to experience sexual satisfaction and suffer from anxiety and depression. The high rates of suicide attempts among these women underscore the severity of their psychological suffering.

Psychotherapeutic treatment can offer relief and a way out of prostitution, helping these women confront and overcome their past traumas. Through therapy, some manage to establish healthier relationships and embark on new legitimate careers, finally finding a measure of stability and emotional peace.[29]

Coping mechanisms

[edit]

"Men would ask me to urinate in bottles so they could drink it, or defecate in their mouths, or bake muffins with my feces for them to eat in front of me. One man offered me $10,000 to have sex with his dog in a film. Another was so brazen that he asked me to play the role of his nine-year-old sister, whom he used to sexually abuse as a teenager."

Female sex workers suffer intense physical, sexual, and mental abuse, widely documented in medical and public health literature. However, the mental coping mechanisms employed by these women to survive have been less studied.[20] In the debate on prostitution, women are often divided into two groups: those who were forced into prostitution and those who 'chose' this activity. The definition of 'force' or 'coercion' can vary, but the underlying logic remains: some women are compelled to prostitute themselves through violence or economic coercion and thus deserve compassion. On the other hand, there are those who seemingly choose it freely, even though they may have other options available, such as access to social services and unemployment benefits.[30]

The reality, however, is more complex. Women from all social classes may find themselves in prostitution due to experiences of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse and may be reenacting these traumas within the realm of prostitution. Rachel Moran argues that prostitution is not only a consequence of women's lack of economic power but exists primarily due to male demand.[30] Prostitution is also seen as a reenactment of previous traumas. Andrea Dworkin mentioned that incest is the training ground for prostitution, indicating that experiences of childhood abuse can predispose women to prostitution. Huschke Mau adds that traumatic situations can become addictive due to the release of adrenaline, a familiar experience for those who have faced violence from a young age.[30]

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu suggests that the body serves as a means of memory for any social order, unconsciously internalizing the structures of social inequality or sexual hierarchies. This means that experiences of violence and degradation become integrated into one's self-perception, profoundly affecting self-esteem and self-worth.[30] Prostituted women often internalize violence and develop dissociative mechanisms to cope with the reality of their situation. Forcing themselves to feel enjoyment during sexual acts is a common strategy to protect themselves psychologically and to meet the expectations of clients, who often need to believe that the women enjoy the sexual interaction to soothe any guilt about their actions.[30] Prostitution also plays a role in maintaining the second-class status of all women within the gender hierarchy. Michael Meuser describes how spaces reserved exclusively for men allow them to reinforce their dominance and normalize social dynamics that perpetuate male supremacy. Therefore, the existence of prostitution has adverse effects not only on prostituted women but on all women in society.[30]

Leaving prostitution is a long and complex process that involves not only finding a new source of income but also readjusting to daily life outside the sex trade. Women who manage to exit prostitution often face significant challenges in rebuilding their self-esteem and social integration.[30]

Depersonalization

[edit]"To endure prostitution, you need to split your consciousness from your body, dissociate. The problem is that you can't just put them back together afterward. The body remains disconnected from your soul, from your psyche. You simply stop feeling yourself. It took me several years to learn that what I sometimes feel is hunger and that it means I need to eat something. Or that there is a sensation indicating that I am cold and need to put on some clothes."

"Even when I tried to dissociate during those countless paid rapes, I found it difficult to separate what was happening to my body from my real self."

Dissociation is a psychological process in which a person disconnects from their thoughts, feelings, memories, or identity. This phenomenon is especially prevalent in individuals who have experienced severe traumas, such as childhood sexual abuse. Dissociation can manifest in various ways, from amnesia to the creation of multiple identities, known as multiple personality disorder (MPD).[34]

Dissociative identity disorder (DID), formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder, is a condition often misunderstood and sensationalized in the media. However, various studies have revealed that between 1 and 3% of the general population meet the diagnostic criteria for DID.[35]

Various studies have investigated the relationship between child sexual abuse and dissociative disorders. The disorder most commonly associated with childhood sexual abuse is multiple personality disorder.[34] In a study by Colin A. Ross and colleagues, 236 people with MPD were examined, and a high prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and dissociation was found. This study also highlighted that, in addition to MPD, prostitution and work in the adult entertainment industry (exotic dancers) showed a significant incidence of dissociative experiences.[34]

To assess the prevalence of dissociation and childhood sexual abuse, tools such as the Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS) and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) were used. These instruments help identify and measure the frequency and severity of dissociative symptoms. In the mentioned study, 60 subjects were included, divided into three groups: 20 patients diagnosed with MPD, 20 sex workers (prostitutes), and 20 exotic dancers. The results showed that most subjects with MPD met the DSM-III-R criteria for the diagnosis of this disorder, and dissociation was common in all three categories of subjects studied.[34]

Causes

[edit]One of the most common causes of DID is childhood sexual abuse. When a child experiences a stressful event such as sexual abuse, the fight or flight response is activated. Dissociation is a form of psychological escape when the child cannot physically escape. The child may imagine that the abuse is happening to another person or another "part" of themselves. If the abuse is severe and prolonged, this "part" can develop its own identity, separate from the child's conscious memory.[35]

Survivors of trauma may exhibit symptoms instead of memories. Many people with DID report memories of childhood traumas and evident symptoms such as "waking up" in unfamiliar places or meeting people who call them by another name. However, it is common for some individuals not to remember their childhood traumas, but to exhibit more subtle and difficult-to-recognize symptoms of PTSD and DID. These symptoms include inexplicable feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness, emotional numbness, concentration problems, thought insertion, Depersonalization and Derealization. Without known traumatic memories to attribute these symptoms to, the person is often misdiagnosed and only superficial problems are treated, masking their true needs.[35]

Many trafficking victims have histories of child sexual abuse, a primary cause of PTSD and DID. Additionally, studies have shown that women in prostitution experience PTSD levels comparable to those of combat veterans. It has also been found that 35% of prostituted individuals and 80% of exotic dancers experience dissociative disorders, and between 5% and 18% of prostituted individuals and 35% of exotic dancers meet the diagnostic criteria for DID.[35]

Religion

[edit]"Our work is quite terrible, isn't it? [...] now only death, because leaving this only after God takes us away... dealing with strange men touching your body... It's horrible, like being in an anthill, it's scary, in my opinion, being in an anthill, someone touching you and you don't like that man... God forbid. Because entering this boat, it seems like an entity, a thing... Can you imagine? Being a normal person, and one comes, another comes and you have to do the job... You're there only for the money, you don't enjoy it or anything. We become cold people, I don't know, I think it's a demonic thing, but we cling to God and move on... It's dangerous work... And dirty."

Women in prostitution often turn to different religious traditions to address their situation, though with very different approaches. For some, religion presents an escape route, offering spiritual redemption and a fresh start. Some Pentecostal churches in Brazil have provided emotional and community support, encouraging women to leave prostitution through conversion, abandoning sinful behaviors, and integrating into a community that values their new moral identity.[37]

In contrast, Afro-Brazilian religions such as Umbanda and Candomblé provide tools to improve their economic success within prostitution. Through rituals and offerings to entities like Pombagira, these women seek to attract more clients and increase their income. These practices reflect a pragmatic and materialistic relationship with the divine, based on the belief that spiritual entities can grant favors and material success in exchange for specific offerings.[38]

Umbanda

[edit]Erika Bourguignon explored dissociative phenomena in different cultural contexts. In her research, Bourguignon compared dissociative cases, such as a woman in New York and a man in São Paulo, showing how dissociation manifests in culturally specific ways. In the context of Umbanda, an Afro-Brazilian religion, dissociative states are interpreted as spiritual possession, where the individual acts as a medium for ancestral spirits. These experiences are not seen as pathologies but as mediumistic abilities that require development and acceptance within the religious community.[38] For prostitutes, dissociation can be a necessary strategy to manage the dissonance between their personal identity and the demands of their work. This mental separation allows them to perform sexual acts without involving their true selves, creating a psychological barrier that protects their mental health. These dissociative experiences enable the individual to face stressful situations without being completely overwhelmed by them.[38]

Bernstein and Putnam propose a continuum for dissociation in the psychopathological dimension, suggesting that not all dissociative experiences are inherently pathological. This perspective is useful for understanding how prostitutes use dissociation as a tool to survive emotionally and psychologically in a hostile environment.[38] In practice, prostitutes may experience a variety of dissociative states, from feeling like external observers of their own bodies to adopting alternative identities that handle interactions with clients. These identities can act as a form of self-protection, allowing women to fulfill their work without feeling the direct emotional impact.[38]

Pombagira

[edit]In Brazil, many women in prostitution turn to spiritual and mystical practices to increase their income. These women frequent spiritist houses and candomblé or umbanda terreiros, where they are advised to buy herbs for baths and products for offerings to spiritual entities like the Lady of the Night or Pombagira. The belief is that these rituals will attract more clients and, therefore, generate higher income.[39] For each entity, the offerings vary and include drinks, perfumes, and red objects. Although some women express skepticism towards these beliefs, many attribute financial success to their participation in these rituals. It is noted that older women often have more economic success than their younger counterparts, attributed to their involvement in these spiritual practices.[39]

The cost of these rituals can be significant. Some women report spending large sums of money on products for offerings, with the promise of obtaining greater profits. However, there is a mixed perception of the effectiveness of these rituals, as although they may attract more clients, the associated cost of offerings may not be compensatory.[39]

Pombagira is a central figure in these spiritual practices, seen as a powerful entity capable of performing "miracles" and attracting success in love, relationships, and material progress. This entity is associated with manipulating sensuality and sexuality and is believed to remove obstacles and enemies to ensure the success of her devotees.[39] The beliefs surrounding Pombagira are not limited to prostitution. In the Brazilian social imagination, Pombagira represents the archetype of the ritual prostitute and is commonly requested to perform works on romantic relationships. Although not all Pombagiras are considered prostitutes, the connection with prostitution is due to her representation as a free and powerful woman.[39] Women in prostitution who participate in these spiritual practices do so under the principle of reciprocity. They offer objects and perform rituals in exchange for economic favors and success in their profession. This system of exchange reflects similar practices in popular Catholicism, where people make promises to saints in exchange for divine favors. However, in prostitution, these offerings are primarily aimed at improving sexual attraction and financial success.[39]

The article "A Pomba-Gira in the Imagination of Prostitutes," published in the journal "Man, Time, and Space," examines the relationship between prostitutes and Pomba-Gira, an entity from the Umbanda pantheon known for her free manifestation of female genital power. This study, conducted by Francisco Gleidson Vieira dos Santos and Simone Simões Ferreira Soares, delves into the symbolic and psychological importance of Pomba-Gira in the lives of prostitutes. Pomba-Gira represents a powerful archetype in Umbanda, characterized by attributes associated with sexuality, disobedience, and the transgression of social norms.[40] From a deep psychological perspective, this entity can be interpreted as a projection of the collective unconscious of prostitutes, who find in her a figure of empowerment and resistance. Identifying with Pomba-Gira allows prostitutes to negotiate their self-esteem and sense of agency in a social context that stigmatizes and marginalizes them.[40]

In psychological terms, the figure of Pomba-Gira could be seen as a manifestation of a dissociative personality in prostitutes, emerging as a defense mechanism against the adversity of their environment. Dissociation is a psychological process by which a person can divide their identity into different states or personalities to face difficult or traumatic situations. In this case, Pomba-Gira would serve as an alternative personality, allowing prostitutes to perform their work more bearably and with less emotional pain.[40] Pomba-Gira, with her defiant character and celebration of free sexuality, offers an alternative narrative to the guilt and shame commonly associated with prostitution. This identification with a powerful and transgressive entity can help prostitutes reconnect with repressed aspects of their identity and find a sense of dignity and worth in a sacred context. By incorporating Pomba-Gira during rituals, prostitutes can experience a form of catharsis, temporarily freeing themselves from the emotional burdens of their daily reality.[40]

Monique Augras, cited in the study, suggests that Pomba-Gira is a Brazilian creation that emerged from the destitution of the sexual characteristics of Iemanjá, another Umbanda figure syncretized with the Immaculate Conception. This new entity channels the most scandalous aspects of female sexuality, directly confronting patriarchal values. From a Jungian point of view, Pomba-Gira could be seen as a manifestation of the anima, representing the erotic and autonomous dimension of the female unconscious that challenges the restrictions imposed by patriarchal society.[40] Interviews with "fathers-of-saint" and other Umbanda practitioners reveal that Pombas-Giras are considered complex and powerful figures, revered for their ability to influence matters of love and desire. This reverence is reflected in ritual practices, where Pombas-Giras, when incorporated by mediums, act as agents of transformation and empowerment. This allows prostitutes to assert their value and dignity in a sacred context.[40]

Positive identity

[edit]"I am of the opinion that no woman, except those who are placed when they are minors to be exploited, becomes a sex worker without her consent. I am totally against that kind of discourse that says we need someone to get us off this path."

One of the fundamental principles of social identity theory is that individuals seek to enhance their self-esteem through their social identities, and an important component of self-definition is occupational identity.[42] Individuals employed as prostitutes constantly engage in various ideological techniques to neutralize the negative connotations associated with the work they do. Ashforth and Kreiner identified three of these techniques: restructuring, recalibration, and refocusing, which are used at the group level to transform the meaning of stigmatized work. Restructuring allows prostitutes to transform stigma into a symbol of honor by asserting that they provide an educational and therapeutic service rather than selling their bodies.[42]

These protective techniques enhance the self-definition of prostitutes and can be considered coping mechanisms. However, engaging in these techniques requires mental and emotional energy, which can become a stressor.[42] Additionally, the requirement for a strong group culture to support these ideological techniques is not always present for prostitutes. Even with efforts to adopt these techniques, most members of occupations considered "dirty work" maintain some ambivalence about their jobs, as they remain part of a broader society that stigmatizes their labor as "dirty" and have continuous contact with people outside their occupation.[42] Prostitutes also have to construct their self-identity in circumstances that put pressure on the relationship between their professional and personal lives. The bodies of prostitutes, and potentially their psyches, are consumed by the client in the act of commercial sex, creating additional pressure to maintain a division between the professional and the personal. Many of the techniques that prostitutes use to maintain this division are considered coping mechanisms.[42]

Emotional labor in prostitution

[edit]Emotional labor is defined as the "act of displaying organizationally desired emotions during service transactions." Emotional labor is believed to be more prevalent in service occupations, as people working in services are generally subject to stricter norms about the appropriate expression of emotions in certain situations.[42] In particular, what is disturbing for people is the imbalance or dissonance between what the worker feels and the emotions they must display. This discrepancy between felt and expressed emotions has a negative effect on physical health.[42]

Prostitutes face very different demands compared to the general population regarding the emotional labor required. Their work consists of acts that are intensely personal and intimate. They must fake affection and emotion to develop a regular clientele. One way that prostitutes cope with the emotional demands imposed on them is by "categorizing different types of sexual encounters [as] relational, professional, or recreational."[42] This way, they can maintain distance from the encounter with the client and preserve their self-identity. The literature also suggests that prostitutes maintain emotional distance by using condoms at work or during professional sex and by refusing to kiss clients. Kissing "is rejected because it is too similar to the kind of behavior one would engage in with a non-commercial partner; it implies too much genuine desire and love for the other person."[42]

Use of stimulation and pleasure

[edit]Pleasure and pain are more related than they seem. Under certain circumstances, pain can intensify sensations of pleasure due to the release of endorphins and other chemicals in the brain. This mechanism is similar to the "runner's high" that athletes experience after an intense exercise session.[43] The relationship between pleasure and pain in the human brain is intricate. They share similar neuronal pathways, allowing the brain to modulate pleasurable experiences to counteract pain. This neurochemical capability can explain how some sex workers find pleasure in their interactions, using it as a way to dissociate from the physical and emotional pain that often accompanies their work. The release of neurotransmitters such as endorphins during these moments can provide temporary relief and a sense of well-being.[44][45]

Prostitution involves practices aimed at minimizing physical issues, although these same practices can generate psychological complications. Sex workers use stimulation and pleasure to reduce physical pain, which, paradoxically, can lead to significant emotional disconnection.[46]

Some clients seek not only to receive pleasure but also to provide pleasure to the worker. For example, a client may pay to give a massage and provide sexual pleasure, which can result in a gratifying experience for both. This type of interaction can go beyond the negative stereotypes associated with sex work, showing that it does not always involve exploitation or abuse.[47] A study by Elizabeth Megan Smith of La Trobe University, published in the journal Sexualities, investigated how sex workers integrate pleasure into their work. This study, titled "'It gets very intimate for me': Discursive boundaries of pleasure and performance in sex work," involved nine women from the sex industry in Victoria, Australia. Through narratives and photographs, the participants explored their relationship with intimacy, performance, and pleasure.[46] The study shows that sex workers often experience pleasure during their work to achieve better vaginal lubrication, reducing the risk of tears and other physical injuries. However, this pursuit of pleasure is not inherently positive.

Some sex workers emphasize the importance of focusing on their own pleasure to maintain a sexual experience and avoid resentment towards clients and the work itself. The ability to reach orgasm can be a strategy to preserve personal integrity.[48] For many, forcing oneself to feel pleasure in unwanted situations can be a survival strategy to avoid physical pain but comes at a high psychological cost.[46] Sex workers may experience a diminished ability to form genuine emotional connections outside of work, leading to feelings of isolation and difficulties in their personal relationships.[46]

Stockholm syndrome

[edit]Stockholm syndrome, a phenomenon where victims develop bonds with their captors as a survival strategy, has been mentioned in the media in relation to this vulnerable population, but it has not been formally investigated. The four main criteria of Stockholm syndrome (perceived threat to survival, displays of kindness by the captor, isolation from other perspectives, perception of inability to escape) have been identified in the narrative accounts of these women.[20]

The threat can be explicit, like physical violence, or more subtle, like emotional abuse or the threat of harm. Victims may believe they cannot survive without the abuser's protection and support and may feel responsible for the safety of others, such as their families.[49] The perception of kindness, even in the smallest form, can be disproportionate due to the victim's low self-esteem. These victims may interpret any cessation of violence or minimal gesture as an act of kindness and may downplay their situation with thoughts like "at least he didn't..." or "it could have been worse".[49]

The first criterion of Stockholm syndrome is the perception of a threat to survival and the belief that the captor would carry out that threat. Many trafficked women experience physical violence and torture, perpetrated by brothel workers (pimps, traffickers, madams) as well as clients. The second condition is the captor's display of love or kindness.[20] Many women maintain relationships with their traffickers or develop bonds with clients, often hoping to start a family with them. This "act of kindness" can be any action that helps the woman survive, as her survival is essential for the functioning of the sex market. The third condition is isolation from the outside world. Many women described their first months in the brothel as completely isolated, contributing to Depersonalization and demoralization. The fourth condition is the perception of inability to escape. Sex workers who attempted to escape were publicly beaten to deter others from trying.[20]

Rescued sex workers refuse to testify against their traffickers, a behavior observed in countries like the United States, England, and India. The closest psychiatric diagnoses to the traumas suffered by these women are complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) and disorders of extreme stress not otherwise specified (DESNOS),[20] but these are not included in the DSM IV due to debates about their distinction from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Stockholm syndrome could be an additional explanation for this behavior, as the conditions described for this syndrome are present in the accounts of sex workers.[20]

Addictions

[edit]The relationship between prostitution and addiction is a complex phenomenon involving multiple psychological, social, and economic factors. Many individuals involved in prostitution may have experienced significant traumas in their lives, such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse during childhood. These traumas often contribute to mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, which can predispose a person to develop addictions as a coping mechanism.[50] Individuals involved in prostitution and struggling with addictions often experience a range of negative psychological effects. Shame, guilt, and low self-esteem are common, exacerbated by social stigma and negative self-perception. Addiction, in turn, can lead to further social alienation and isolation, reinforcing these negative feelings and contributing to the persistence of addictive behavior.[50]

Emotional and sexual addiction

[edit]"When it's a handsome man and he does it well, I win. I feel desired, satisfied, and I also earn money for feeling pleasure. Is there anything better?... Some pay me just to cry, vent, and receive affection. Some nights, I play the role of a psychologist."

Involvement in prostitution is not always driven solely by economic reasons. Psychological and emotional factors play a significant role. Some individuals in sex work may experience addictions related to seeking validation, the need to control trauma, or as a way to cope with stress and anxiety. Childhood trauma and prolonged stress can alter brain responses, increasing susceptibility to addictive behaviors, not necessarily related to substances but to activities that generate a sense of reward, such as commercial sex.[52][53] Some women in prostitution find this activity a way to exert power and control, especially if they have suffered traumas or seek to regain a sense of agency in their lives. This control can be a way to manage their self-esteem and feel validated through men's attention and desire. Additionally, some seek prostitution as a form of emotional independence and autonomy from adverse personal situations.[54]

Some studies highlight that not all individuals in sex work are there due to extreme economic need; some choose this profession for the exploration of their sexuality and the financial independence it offers. For some, prostitution offers a temporary escape from personal problems and a sense of empowerment, despite significant risks to their physical and emotional well-being.[55]

"There will be a woman whose dream and pleasure is this, to have everything she finds here. Everything. Even the fights, the confusions attract to tell the truth, even the problems, what you have in the area, sometimes, when you leave, you miss it."

This addiction is not always driven solely by the desire for money but also by the need for validation and power over their clients. Compulsive sexual behavior can cause changes in brain circuits, leading individuals to seek more intense sexual encounters to achieve the same satisfaction, similar to other addictions such as drugs or alcohol.[56] Additionally, prostitutes can be influenced and develop addictive behaviors due to constant interaction with clients who have sexual addictions. Repeated exposure to these compulsive behaviors can contribute to sex workers developing similar addictions, either seeking emotional validation or feeling a compulsive need to engage in sexual activities to gain a sense of control and power.[57] Besides sex and the need for validation, prostitutes can also develop addictions to behaviors such as gambling, compulsive shopping, excessive exercise, and social media use. These behavioral addictions are similar to substance addictions in how they affect the brain and can lead to financial, health, and personal relationship problems.[57][58] However, prostitution is rarely a completely free choice when options are limited, and socio-economic conditions are adverse.[59]

Addiction to cosmetic surgeries

[edit]Sex workers often resort to cosmetic procedures to enhance their appearance, hoping to increase their attractiveness and, consequently, their income. This trend is especially notable in countries like Colombia, where the cosmetic surgery industry is booming.[60]

Prostitutes may undergo multiple surgeries to achieve an ideal of beauty influenced by cultural norms and client demands. This pursuit of physical perfection can become an addiction similar to other behavioral addictions, where individuals continuously seek surgical procedures despite potential negative risks. This addictive behavior is often related to psychological disorders such as body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a mental condition where individuals are excessively concerned about perceived defects in their appearance.[60]

Substance abuse

[edit]"At some point, I also got hooked on sleeping pills, very common among us, prostituted women who are anxious and unable to disconnect at night."

People engaged in prostitution are predominantly women, although men are also involved. There are various types of prostitution, from high-end escort services to street-level services. In the United States, prostitution is illegal except in some counties in Nevada. Women in street prostitution often face greater social and legal consequences, including high rates of arrest, incarceration, violence, and victimization, as well as health, mental health, and substance abuse issues.

"I dressed very provocatively when I was nine or ten years old, started experimenting with chemical drugs at 13, and lost my virginity just after turning fourteen to an older boy who pressured me until I finally gave in. From age 16, I spent three years dating a crack dealer who emotionally abused me with belittling and controlling tactics. He then cheated on me, gave me chlamydia, and eventually started physically abusing me."

Substance abuse is common among women in prostitution, including the use of heroin, cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol. Some women start prostituting to fund their drug use, while others develop substance abuse problems after becoming involved in prostitution. Substance use can provide women with a coping mechanism for the difficulties of prostitution.[61] Most women in prostitution have experienced violent events throughout their lives, often from childhood. There is a high prevalence of childhood sexual abuse among women in prostitution, and many also face violence in their intimate relationships and within the context of prostitution. These experiences of violence and trauma throughout life place women at risk of developing disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and other related issues.[61]

The high levels of substance abuse and trauma among women in prostitution suggest the need for programs that address both issues comprehensively. This study aims to inform the implementation of the SPD and highlight the importance of developing and implementing effective interventions for this population.[61]

Recidivism

[edit]For some, dissatisfaction and increasing emotional distress prompted periods of disengagement from sex work, ranging from days to years, or the beginning of what they described as their exit from sex work.[62] However, for most, these breaks were short-lived, and emotional and financial difficulties led them back. Emotional and financial difficulties were frequently interconnected, as drug addiction as a means of emotional management created economic problems.[62] Participants struggled with limited monetary benefits and faced significant barriers to accessing alternative employment and educational opportunities. Women reported few options for earning quick money, making them return to sex work as an immediate solution to urgent financial needs. Despite not necessarily wanting to return, sex work was seen as an easy way out in situations of extreme economic need. Even those who tried to leave sex work found it difficult to refuse face-to-face propositions or calls from regular clients. Once experienced in sex work, alternative options seemed scarce, and sex work offered a level of familiarity and flexibility.[62] Additionally, for some, it was important to avoid the time restrictions and obligations associated with formal employment, preferring to avoid the legal implications of criminal activities such as theft.[62] Substance use often drove the need to earn quick money with few obligations, although some women described how sex work met basic needs and then became accustomed to the extra money. In addition to financial appeal, some participants were drawn back to sex work seeking companionship, purpose, and relief from loneliness and boredom.[62] Returning to sex work offered a sense of belonging, especially for those with limited family contacts or loss of custody of their children due to drug problems. Although some women accessed activities in support services, they reported a limited range of self-directed leisure activities, sometimes leading them back to sex work due to boredom.[62]

Psychological consequences

[edit]Post-traumatic stress disorder

[edit]

One of the strongest psychological effects of prostitution on sex workers is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is described as episodes of anxiety, depression, insomnia, irritability, recurrent memories, emotional numbness, and hypervigilance. PTSD symptoms are more severe and long-lasting when the stressor is a person. According to Melissa Farley, "PTSD is normative among prostituted women." In San Francisco, Farley conducted a study with 130 prostitutes, 55% of whom reported being sexually assaulted in childhood and 49% reported being physically assaulted in childhood. As adults in prostitution: 82% had been physically assaulted, 83% had been threatened with a weapon, 68% had been raped while working as prostitutes, and 84% reported being homeless at some point. According to the 130 people interviewed, 68% met the DSM III-R criteria for a PTSD diagnosis. Farley notes that 73% of the 473 people interviewed in five different countries (South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, US, and Zambia) reported being assaulted in prostitution and 62% had been raped in prostitution. Any prostitute who experiences trauma can develop PTSD. Research found that of the 500 prostitutes interviewed worldwide, 67% suffer from PTSD.

I have experienced horrible, disgusting, and traumatizing things that no person should ever endure. I have had men force me to perform sexual acts... They violently sodomized me, strangled me, photographed and filmed me having sex without my knowledge or consent, and some men used me so forcefully that my genitals and anus were torn and bleeding. I have had men so obsessed that they contacted me hundreds of times a day, followed me home, and randomly showed up knocking on my door in the middle of the night. I have been raped numerous times without a condom.

— Andrea Heinz, former prostitute.[22]

The study titled "Prostitution in Five Countries: Violence and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" conducted by Melissa Farley, Isin Baral, Merab Kiremire, and Ufuk Sezgin and published in Feminism & Psychology in 1998 investigates the prevalence of violence and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among prostituted individuals in South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, the United States, and Zambia. The research, based on interviews with 475 individuals in prostitution, shows that 73% of respondents reported being physically assaulted, 62% reported being raped, and 67% met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The study also examines differences in experiences of violence by location of prostitution (street or brothel) and race, although it found no significant variations in the severity of PTSD among different groups. The data indicate that prostitution inherently carries a high risk of violence and psychological trauma, regardless of the cultural or legal context. Additionally, an average of 92% of respondents expressed a desire to leave prostitution, needing support such as job training, healthcare, and physical protection. The research demonstrates that prostitution is a form of violence against women and raises serious implications for public policies and support programs aimed at individuals in prostitution.[63]

| Variable | Current PTSD % (N = 22) | No current PTSD (N = 50) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Mean age in years | 34 | 33 |

| Homeless in the past 12 months | 50 (11) | 42 (21) |

| Median years of schooling | 9 | 9 |

| A&TSI status | 27 (6) | 20 (10) |

| Drug use | ||

| Median age at first use of injectable drugs | 17 | 18 |

| Drug dependence | ||

| Heroin dependence | 73 (16) | 86 (43) |

| Cocaine dependence | 32 (7) | 38 (19) |

| Cannabis dependence | 36 (8) | 30 (15) |

| Shared injection equipment in the last month | 20 (4) | 40 (19) |

| Sex work and risky sexual behaviors | ||

| Median age at starting sex work | 20 | 18 |

| Always uses condoms when having sex with clients | 91 (20) | 83 (39) |

| Always uses condoms during oral sex with clients | 62 (13) | 60 (28) |

| Mental health and trauma | ||

| Median number of traumas experienced | 7** | 5 |

| Severe depressive symptoms | 73+ (16) | 48 (23) |

| Suicide attempt | 50 (11) | 40 (19) |

| Experienced physical assault while working | 77 (17) | 77 (39) |

| Ever experienced childhood sexual abuse | 82 (18) | 72 (36) |

| Ever experienced childhood neglect | 59* (13) | 28 (14) |

| Ever experienced adult sexual assault | 82* (18) | 53 (26) |

| Median age at first sexual assault | 13 | 14 |

| Source: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Female Street-Based Sex Workers in the Greater Sydney Area, Australia.[16] | ||

The table provides a detailed comparison between sex workers with current PTSD and those without current PTSD, focusing on several key dimensions: demographics, drug use, risky sexual behaviors, and mental health and trauma experiences.[16]

In terms of demographics, the mean age of women with current PTSD is 34 years, similar to women without current PTSD, who have a mean age of 33 years. Both cohorts have a median of 9 years of schooling. However, a notable difference is the rate of homelessness in the past 12 months, which is 50% among women with current PTSD, compared to 42% in women without current PTSD. Additionally, A&TSI (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) status is more prevalent among women with current PTSD (27% vs. 20%).[16]

Regarding recreational drug use, the median age at first use of injectable drugs is slightly lower in women with current PTSD (17 years) compared to those without current PTSD (18 years). The rates of heroin dependence are high in both cohorts, though slightly lower in women with current PTSD (73% vs. 86%). Dependence on cocaine and cannabis is also relevant, with similar percentages between both groups. However, a significant finding is that 20% of women with current PTSD shared injection equipment in the last month, compared to 40% of those without current PTSD, suggesting possible differences in risk behaviors related to drug use.[16]

In terms of risky sexual behaviors, the median age at starting sex work is slightly higher in women with current PTSD (20 years) compared to those without current PTSD (18 years). The prevalence of condom use is high in both groups, both during sex with clients (91% for current PTSD and 83% for no current PTSD) and during oral sex with clients (62% for current PTSD and 60% for no current PTSD). This indicates a high level of awareness about protection in both groups.[16]