KV36

| KV36 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Maiherpri | |

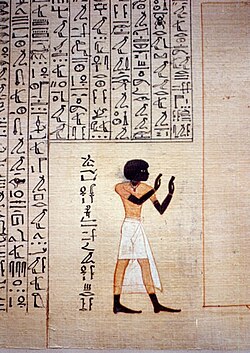

Depiction of Maiherpri in his Book of the Dead papyrus | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′22.4″N 32°36′0.2″E / 25.739556°N 32.600056°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | March 1899 |

| Excavated by | Victor Loret |

| Decoration | Undecorated |

← Previous KV35 Next → KV37 | |

Tomb KV36 is the burial place of the noble Maiherpri of the Eighteenth Dynasty in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

Rediscovered on 30 March 1899 by Victor Loret in his second season in the Valley of the Kings, the tomb was found to be substantially undisturbed, but as it has for a long time not been properly published, it is not as well known as other burials in the valley.[1] All the objects found were taken to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where they were published in the Catalogue General (short: CG). The only source for the arrangement of the objects in the burial chamber was a short article by Georg Schweinfurth.[2] He visited the tomb briefly before its contents were brought to Cairo. However, recently the notebooks of Loret were found and published, providing a detailed list and description of the objects found and their arrangement in the tomb chamber.[3]

History

[edit]Burial and robbery

[edit]Little is known about Maiherpri as he does not appear in sources outside the tomb. Only two titles appear on the objects within the burial: "child of the kap (nursery)" and "fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King". His Book of the Dead also calls him "companion of the King" and "one who follows the King on his marches to the Northern and Southern foreign countries." Examination of his mummy showed that he was a young man when he died, aged 25-30 years.[4]

He is generally thought to have been buried during the mid-Eighteenth Dynasty, between the reigns of Hatshepsut and Amenhotep III. More specific arguments by the Egyptologists Catharine Roehrig and Christian Orsenigo place his interment in the reigns of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, while writer Dennis C. Forbes considers him a contemporary of Thutmose IV or Amenhotep III.[5]

Maiherpri's tomb was robbed at least once in antiquity. Thieves targeted easily recyclable objects such as clothing and fabric, jewellery, metal vessels, and cosmetics. Vases of oils were investigated but had gone rancid by the time of the robbery and were left in the tomb. His coffins were opened and his mummy was looted of the valuables included in the wrappings.[6] Robbers may have also stolen furniture such as boxes, chests and beds as these were absent from the KV36 but found in more intact contemporary tombs;[7] they seem to have stashed a small box inscribed for Maiherpri and containing two leather loincloths in a cleft above KV36, which was discovered on 26 February 1903 by Howard Carter during his clearance of the area around the tomb.[8][9]

Discovery and clearance

[edit]KV36 was discovered in 1899 during the second season of excavations by the French Egyptologist Victor Loret.[10] The then-director of the Antiquities Service focused his work in the southern Valley of the Kings, opening test pits or trenches to the bedrock (sondage) in likely-looking locations.[11][12] A map of the valley annotated by him indicates approximately 15 test excavations were sunk in the general vicinity of KV36 prior to its discovery.[13]

The tomb was discovered on 30 March 1899 in approximately the 16th test pit, cut into the gravel near the base of the cliffs to the south of the tomb of Amenhotep II.[14] At the base of the shaft was a partial blocking closing the door of the chamber. Loret entered the burial chamber on 31 March 1899; it was immediately apparent the tomb had been robbed but still contained much of its furnishings and burial equipment.[13] The large black-painted and gilded sarcophagus sat close to the north wall with a canopic chest at its foot; Loret read the name "Maiherpri" on the sarcophagus' gold inscription. Food offerings and bouquets were piled in the corner and large jars were clustered against the far wall. A large coffin lay overturned in the middle of the room. The rest of the space was strewn with various objects and personal belongings including ceramic and alabaster vessels, archery equipment, and two dog collars.[15][16]

The tomb was recorded and cleared quickly for fear of robbery, with everything packed into 16 crates by 7 April 1899. At least five photographs were taken of individual objects but none are known that show the chamber as it was discovered. The contents of KV36 were transported from the Valley of the Kings to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo which was housed in the former palace of Khedive Isma'il Pasha; when the new museum building opened in 1902 in Tahrir Square, they were displayed in their own large gallery on the second floor.[17][18]

Very little was known about KV36's excavation until the early 2000s.[10] Loret never published on the discovery and resigned as director of the Antiquities Service at the end of 1899.[11][19] In 2004, a collection of his notes and photographs preserved in the University of Milan, Italy and the Institut de France, Paris were published. Prior to this, the only records available of the tomb's discovery and arrangement of its contents was an account written in 1900 by Georg Schweinfurth[20] who visited the tomb during its clearance, and a list of contents published in 1902 by Georges Daressy[21] in a volume of Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire.[11][13]

Architecture

[edit]KV36 is located in the Valley of the Kings between the tombs of Amenhotep II (KV35) and Bay (KV13),[10] cut into the floor of the valley opposite the entrance of the wadi that contains the tomb of Thutmose III (KV34).[22] The tomb of Maiherpri is a small shaft tomb with a chamber at the bottom on its west side.[10] The burial chamber was undecorated, as with all burial chambers of non-royals in the Valley of the Kings. It is 3.90 m (12.8 ft) long and 4.10 m (13.5 ft) wide[23] with an area of 15.30 m2 (164.7 sq ft).[11]

Burial goods

[edit]KV36 was the first reasonably intact tomb discovered in the Valley of the Kings.[10] Despite robbery in antiquity, it still contained over 100 items.[24] Maiherpri was buried with archery equipment including two leather quivers with Near Eastern decoration, over 50 arrows, and two leather wrist guards; bows were absent, possibly looted by ancient robbers.[25] Orsenigo suggests that these were used for sport hunting rather than warfare based on Maiherpri's lack of military titles.[26]

Also included were two ornate leather dog collars. One has a design of horses separated by lotuses and has a scalloped green border.[27][28] The other has a design of gazelles being hunted by lions[27] or dogs[28] and was once gilded.[29] It bears a two line inscription identifying the dog it belonged to: "tesem of his house, She-of-Thebes" (ṯsm n pr=f tꜣ-n.t-niw.t).[28] The name is transcribed as Ta-ent-niuwt[29] or Tantanuit.[27] Based on these collars, Maiherpri may have been the caretaker of the king's hunting dogs.[30]

Burial

[edit]Maiherpri's body was interred in a set of three coffins. The outermost (CG 24001) is a 2.81 metres (9.2 ft) long rectangular sarcophagus made of black-painted wood with gilded inscriptions and decoration.[31][32] Inside were two nested human-shaped (anthropoid) coffins (CG 24002 and 24004). The outer was also black with gilded decoration, while the inner was entirely gilded; both have curled false beards.[33] There is a third anthropoid coffin (CG 24003) made of untreated wood with gilded inscriptions, which was found overturned next to the sarcophagus with its lid placed next to the box.[34] This caused some confusion and discussion in Egyptology. It seems that this 'extra' coffin was intended as the innermost one, but was actually too big to fit into the set and was therefore left unused next to it. Parallels have been drawn to the burial of Tutankhamun, where the foot of his outermost coffin was slightly too large for the sarcophagus. There the coffin was shortened directly in the tomb chamber, while in the burial of Maiherpri his mummy was placed into the second coffin of his set.[6][35]

The mummy of Maiherpri was adorned with a black and gold cartonnage mummy mask (Cairo GC 24097).[36] The mask completely covers his head and shoulders and is similar in style to that of Hatnofer, the mother of Senenmut, buried in the reign of Hatshepsut.[37] Maiherpri's mummy was disturbed by robbers in antiquity, who sliced through the bandages in search of valuables. The body was formally unwrapped by Georges Daressy on 22 March 1901. He noted that the method of bandaging was entirely horizontal strips with minimal padding; he estimated the body was wrapped in 60 layers of fabric. Pieces of jewellery missed by the robbers included bracelets, pieces of a beaded collar, a scarab, and isolated beads of carnelian and gold. Thieves also missed the gold plate covering the embalming incision.[38][39]

Maiherpri's mummy measures 1.64 m (5.4 ft) tall. He lies on his back with his legs extended. His hands are positioned over the front of his thighs; the right hand is flat while the left is clenched. His head was shaved and wore a tightly curled wig which was glued to his scalp. Daressy considered his dark skin tone to be unchanged by embalming, identifying him as Upper Egyptian or Nubian. He also noted a resemblance to Thutmose IV, as both have the "Thutmosid" overbite. Daressy estimated Maiherpri died in his 20s.[38][39]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 179.

- ^ Schweinfurth 1900, pp. 103–107.

- ^ Orsenigo 2004, pp. 214–221, 271–281.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, pp. 27, 35.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, pp. 35–38.

- ^ a b Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 181.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Forbes 1998, p. 42.

- ^ Roehrig 2005, pp. 70, 74.

- ^ a b c d e Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Orsenigo 2017, p. 24.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Forbes 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 6, 35.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, p. 36-37.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 11–24.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, p. 24-25.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Forbes 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Schweinfurth 1900.

- ^ Daressy 1902.

- ^ Roehrig 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Orsenigo 2004, p. 220.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Forbes 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, pp. 27–30.

- ^ a b c Forbes 1998, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Brixhe 2018, p. 72.

- ^ a b Reisner 1936, p. 99.

- ^ Orsenigo 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Forbes 1998, p. 11.

- ^ Daressy 1902, p. 1.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Forbes 1998, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 106.

- ^ Forbes 1998, p. 17.

- ^ Roehrig 2005, p. 70.

- ^ a b Forbes 1998, pp. 38–41.

- ^ a b Daressy 1902, pp. 58–61.

Works cited

[edit]- Brixhe, Jean (2018). "Deux Colliers de Chien dans la Tombe de Maiherpri". Pharaon: Le Magazine de l'Egypte Éternelle (in French). Vol. 32. pp. 70–73.

- Daressy, Georges (1902). Catalogue Général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire N° 24001-24990: Fouilles de la Vallée des Rois (1898-1899) (in French). Le Caire: Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- Forbes, Dennis C. (1998). Tombs. Treasures. Mummies: Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology in Five Volumes. Book Two, The Tombs of Maiherpri (KV36) & Kha & Merit (TT8) (2015 Reprint ed.). Weaverville: Kmt Communications LLC. ISBN 978-1512371956.

- Orsenigo, Christian (2004). "La Tomba di Maiherperi (KV 36)". In Piacentini, Patrizia; Orsenigo, Christian (eds.). La Valle dei Re Riscoperta: I Giornali di Scavo Victor Loret (1898–1899) e Altri Inediti. Translated by Qurike, Stephen. Mailand. pp. 214–221, 271–281.

- Orsenigo, Christian (2017). "Revisiting KV36 the Tomb of Maiherpri". KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 28, no. 2. pp. 22–38. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- Reeves, Nicholas (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure (2007 ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05146-7. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2000 ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05080-5. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- Reisner, George A. (December 1936). "The Dog Which was Honored by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt". Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. 34 (206): 96–99. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt (2004 ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15448-0. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- Roehrig, Catharine H. (2005). "The Tomb of Maiherpri in the Valley of the Kings". In Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renee; Keller, Cathleen A. (eds.). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 70–74. ISBN 0-300-11139-8. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- Schweinfurth, G. (1900). "Neue Thebanische Gräberfunde". Sphinx (in German). III: 103–107. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to KV36 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to KV36 at Wikimedia Commons- Theban Mapping Project: KV36 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.