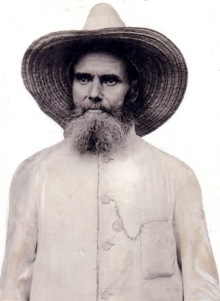

Léopold Louis Joubert

Léopold Louis Joubert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1842 Saint-Herblon, France |

| Died | 27 May 1927 (aged 85) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Known for | Defense of equatorial African missions |

Léopold Louis Joubert (or Ludovic Joubert) (22 February 1842 – 27 May 1927) was a French soldier and lay missionary. He fought for the Papal States between 1860 and 1870 during the Italian unification, which he opposed. He later assisted the White Fathers missionaries in East Africa and played an important role in the suppression of the slave trade between 1885 and 1892. He married a local woman and settled by the shore of Lake Tanganyika, where he lived until his death at the age of eighty five.

Early years

[edit]Léopold Louis Joubert was born at Saint-Herblon, France on 22 February 1842.[1] As a child he wanted to be like the Christian warriors of the past.[2] He was given the nickname "Ludovic" as a child, and was often called by this name as an adult. He attended school at Ancenis (1854–1858) and then Combrée (1858–1860). Joubert left school in 1860 to join the army that Pope Pius IX was raising to defend the Papal States as a member of the Franco-Belgian corps that was later called the Papal Zouaves.[1]

On 18 September 1860 Joubert fought at the Battle of Castelfidardo, where he was wounded, taken prisoner and returned to France. After recovering, he went back to Rome in June 1861, and was appointed Sergeant in 1862. He remained in Rome as a member of the Zouaves after Napoleon III withdrew the French troops from Italy in December 1866. He became a Lieutenant on 30 December 1866 and Captain on 14 December 1867, aged twenty-five.[1] On 20 September 1870 he commanded the defenders of the Porta Salaria during the unsuccessful defense of Rome against the army of the new Kingdom of Italy.[3]

During the Franco-Prussian War General Athanase Charette organized the French Zouaves as a corps of "Volunteers of the West".[4] Joubert served as a captain in this corps but refused an offer of a permanent commission as a captain in the French army, so as to remain at the service of the Pope.[3] After the war ended in 1871 he returned to La Sébilière in Mésanger, where he worked as a farmer until 1879. In 1879 he became secretary to General Charette and tutor to his son.[1] The General was a supporter of the Bourbon monarchy and also a passionate advocate for the Pope's temporal sovereignty.[4]

First African expedition

[edit]

On 15 January 1880 Joubert left Marseille for Algiers where he offered to work as an armed auxiliary protecting the missionaries being dispatched by Archbishop Charles Lavigerie's Society of Missionaries of Africa, or White Fathers. The missionary caravans were menaced by armed slave traders in the Great Lakes region of East Africa. On 8 November 1880 Joubert left Algiers with the third caravan in command of six Zouaves. The caravan arrived at Bagamoyo, opposite Zanzibar, on 3 December 1880.[1] After many delays and difficulties it reached Tabora in what is now Tanzania in December 1881.[5]

Joubert continued on to Ujiji on Lake Tanganyika, which he reached on 7 February 1882.[1] He helped fortify the mission at Mulwewa on the west shore of the lake, and to train the local African defenders. He also helped found missions at the north and south ends of the lake, and was responsible for building the fortified mission of Lavigerieville (Kibanga). Later the missionaries abandoned three of the new stations due to attacks by the powerful slave traders Tippu Tip and Rumaliza. A spitting cobra temporarily blinded Joubert.[5] He had to return to France in May 1885 for treatment.[1]

Concept of the Christian kingdom

[edit]Cardinal Lavigerie was keen on the idea of establishing a central Christian state that could dominate the interior of Africa and ward off the influence of Freemasons, Socialists, Protestants and Muslims. At one point the kingdom of Buganda was seen as potentially playing this role, and Joubert thought he might have to become "Minister of War to His Black Majesty, Mutesa." This idea was abandoned, as was a plan to use the Kingdom of Lunda as a base.[6]

In 1885 the Berlin Conference settled the European colonial spheres of interest in Africa. The area that now consists of Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania (other than Zanzibar) became German East Africa. The Belgian station of Mpala, which had been founded in 1883 by Émile Storms on the west shore of Lake Tanganyika, was militarily isolated now that the stations of Karema and Tabora lay in German territory. King Leopold II of Belgium decided to focus his efforts on the Congo River, and offered Mpala and Karema to Cardinal Lavigerie for White Fathers missions.[3] Lavigerie accepted the offer, thinking Mpala could be the basis for his Christian state, and that if a suitable African leader could not be found "it would not be impossible ... for a brave and Christian European to fill this [responsibility]."[6]

Return to Africa

[edit]

Later in 1885 Joubert again offered his services to Lavigerie, and this was accepted in a letter of 20 February 1886. Joubert reached Zanzibar on 14 June 1886, and reached the mission at Karema on 22 November 1886. He remained there for some months at the request of the Vicar Apostolic, Mgr. Jean-Baptiste-Frézal Charbonnier, to protect the mission against attacks by slavers. He crossed the lake and reached Mpala on 20 March 1887. Charbonnier had given him full authority as civil and military ruler of the Mpala region.[7] Lavigerie later said that Joubert could have become King of Marungu if he had wished.[6]

Joubert found that the priests had already organized a police force of local warriors at Mpala. Immediately after arriving, Joubert was thrown into the struggle with dealers in slaves and ivory. He engaged in skirmishes in March and again in August, where his small force of thirty soldiers armed with rifles came close to defeat. Joubert again had to intervene in November 1887, and in 1888 defeated a force of 80 slavers, but his forces were too small to prevent continued attacks.[7] Later, Joubert created a strong and effective military force from three hundred of Storms's fighters.[8] The constant fighting worried some of the missionaries, notably Father François Coulbois, who were concerned that the slavers might decide to attack the mission itself.[7]

Joubert married Agnes Atakaye on 13 February 1888.[1] They were to have ten children. Two died young, and one became a priest.[9]

When Mgr. Charbonnier died on 16 March 1888, Coulbois became Pro-Vicar of Upper Congo. He did not recognize that Joubert had civil authority, and imposed tight restrictions on his actions. Both men appealed for support to Cardinal Lavigerie. In response, Lavigerie said that the missionaries must have no involvement with military affairs, and the military leader must live at a distance from the mission to avoid being identified with the mission. The new Vicar Apostolic, Bishop Léonce Bridoux, arrived in January 1889. He confirmed that Joubert was both civil and military leader, but said that military operations must be purely defensive.[7]

Joubert moved to St Louis de Murumbi, some distance away.[7] This was a fortified village that he built three leagues from Mrumbi mountain, a days walk from Mpala and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the shore of the lake. His voluminous correspondence with his brother in France and with General de Charette is often dated from this village.[10] A visitor to St. Louis Mrumbi in 1891 met Joubert. He said that he "... appeared to be about forty-five years of age, short, but very sturdily built.[11] He said of the station,

The spot was extremely picturesque, and appeared to have been selected with a keen eye to defensive purposes. Captain Joubert had surrounded his village with a brick wall fourteen feet high and two and a half thick; while a short distance off, separated by a deep gully, stood a second city of refuge, comprising his house and barracks, surrounded by another wall. Close at hand he had built a chapel, capable of holding about two hundred people, with a sacristy and sleeping-room at the back for Father Van Oost, a Belgian, who used to come for service from the Mpala mission, about a day's journey to the north.[11]

Isolation

[edit]In January 1889 the mission was cut off from the outside world by Abushiri Revolt against the Germans in Bagamoyo and Dar es Salaam.[7] Joubert was to receive no mail for three years.[12] The mission suffered from repeated and deadly raids.[7] Around the end of May 1890, while Joubert was absent, a group of Arabs[a] prepared to cross the Lukuga River[b] about 100 kilometres (62 mi) to the north of Mpala. Some skirmishing occurred between the Arabs and the mission's African forces before Joubert could reach the scene. The Arabs tried to negotiate with the missionaries, saying they would not harm the mission if the priests abandoned Joubert. Bridoux refused. It seemed that serious fighting was going to break out, when a storm arose that destroyed some of the Arab fleet and forced them to withdraw.[15] Rumaliza remained determined to eliminate Joubert, who was disrupting the slave trade.[10] By 1891 the slavers had control of the entire western shore of the lake apart from the region defended by Joubert around Mpala and St Louis de Mrumbi.[5] Joubert called for help from Europe.[10]

Joubert's status was ambiguous. The Belgians had appointed Tippu Tip as their lieutenant in the region, but Joubert refused to recognize the authority of the slaver.[16] During a lull in January 1891, Father I. Moinet visited Ujiji. There he found Rumaliza flying a German flag and saying he was waiting for the Germans to arrive so he could hand over to them. In a letter to Joubert in April 1891, Rumaliza asked if he was employed by the missionaries or by the government of the Congo. Joubert was evasive in his reply, pointing out that Rumaliza sometimes flew the German flag, sometimes the flag of Zanzibar and sometimes that of Britain.[17]

A Belgian relief expedition was organized. It was led by Captain Alphonse Jacques and three other Europeans, and reached Zanzibar in June 1891, Karema on 16 October 1891 and Mpala on 30 October 1891.[7] When the Jacques expedition arrived Joubert's garrison was down to about two hundred men, poorly armed with "a most miscellaneous assortment of chassepots, Remingtons and muzzle-loaders, without suitable cartridges." He also had hardly any medicine left.[18]

Captain Jacques gave Captain Joubert papers that made him a Congo citizen and officer of the Congo armed forces.[19][c] Jacques asked Joubert to remain on the defensive while he moved north, founded the fortress of Albertville and tried to suppress slaving.[19] Sporadic fighting with the Arabs continued in 1892. The danger from slavers was not finally removed until the 1893 expedition of Baron Francis Dhanis.[7] The European press was critical of these actions, described by Le Soir in July 1892 as the "military adventures of Cardinal Lavigerie".[5]

Later career

[edit]

In the mid-1890s the agents of the Congo Free State were directed to assimilate the Christian Kingdom on the west of Lake Tanganyika. The former "king" Joubert was removed from any significant authority. For a period Marungu fell into lawlessness.[20] The Belgian State decorated Joubert in 1896. In 1898 the Force Publique of the Congo mutinied, and for some time the area around Lake Tanganyika was threatened by rebels. After this the region became peaceful.[5] Both the King of Belgium and the Pope later knighted Joubert.[21]

After laying down his arms, Joubert became a catechist, teacher and medical worker.[9] He lived on at St Louis de Murumbi until 1910, when it was abandoned due to sleeping sickness. He then founded the mission of Sainte Marie of Moba, at Misembe on the western lake shore to the south of Mpala.[7] In his last years Joubert became both blind and deaf. He died on 27 May 1927 at the age of 85 after having lived on the shores of Lake Tanganyika for 46 years.[9] Joubert was buried in Baudouinville Cathedral.[5] In 1933 a committee in Brussels commissioned the sculptor Jules Jourdan to create a medallion of Joubert based on photographs. This adorns the rustic memorial that the White Fathers erected in his memory on the heights overlooking the lake at Baudouinville.[22]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The slavers included Arabs from Zanzibar and other coastal settlements and Swahili, also from the coastal region. The two groups had intermarried. The Swahili were Muslim and had adopted Arab dress and other Arab cultural traditions. Their Bantu-origin language had absorbed many Arabic loan words. Swahili traders had penetrated far into the interior, and their language was the lingua franca throughout East Africa and the eastern Congo basin.[13] Contemporary European sources often use the word "Arab" to refer to both groups.

- ^ The Lukaga River drains Lake Tanganyika to the Lualaba, or Upper Congo. It leaves the lake at modern-day Kalemie, 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) to the north of the station of Albertville that Captain Jacques founded on 30 December 1891.[14]

- ^ Joubert was the only white to be made a citizen of the Congo Free State.[9]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h Il y a 80 ans ...

- ^ Coulombe 2009, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Coosemans 1951, p. 517.

- ^ a b Goyau 1914.

- ^ a b c d e f Shorter 2003.

- ^ a b c Vail 1991, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Casier 1987.

- ^ Swann 2012, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Cheza 2005, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Coosemans 1951, p. 518.

- ^ a b Moloney 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Vail 1991, p. 211.

- ^ Lockard 2007, p. 336.

- ^ Auzias & Labourdette 2006, p. 211.

- ^ Swann 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Swann 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Swann 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Moloney 2007, p. 96.

- ^ a b Swann 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Vail 1991, p. 198.

- ^ Coulombe 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Coosemans 1951, p. 519.

Sources

- Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (2006). Congo: république démocratique. Petit Futé. p. 211. ISBN 978-2-7469-1412-4.

- Casier, P. Jacques (1987). "Le royaume chrétien de Mpala : 1887 – 1893". Souvenirs Historiques (in French) (13). Nuntiuncula, Bruxelles. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Cheza, Maurice (2005). "L'accompagnement arme- des missionaires dans l'Afrique des Grand Lacs: Les cas de Joubert et Vrithoff". Les conditions matérielles de la mission: contraintes, dépassements et imaginaires, XVIIe-XXe siècles : Actes du colloque conjoint du CREDIC, de l'AFOM et du Centre Vincent Lebbe : Belley (Ain) du 31 août au 3 septembre 2004 (in French). KARTHALA Editions. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-84586-682-9.

- Coosemans, M. (1951). "JOUBERT (Leopold Louis)". Biographie Coloniale Belge (in French). Vol. II. Inst. roy. colon. belge. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- Coulombe, Charles A. (2009). The Pope's Legion: The Multinational Fighting Force that Defended the Vatican. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61756-8.

- Goyau, Georges (1914). "Baron Athanase-Charles-Marie Charette de la Contrie". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 16 (Index). New York: The Encyclopedia Press. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- "Il y a 80 ans, le 27 Mai 1927, Mourait le Captiaine Joubert" (in French). Lavigerie. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Lockard, Craig A. (10 January 2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History: To 1500. Cengage Learning. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-618-38612-3.

- Moloney, Joseph Augustus (2007). With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–1892. Jeppestown Press. ISBN 978-0-9553936-5-5.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003). "Joubert, Leopold Louis". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- Swann, Alfred J. (2012). Fighting the Slave Hunters in Central Africa: A Record of Twenty-Six Years of Travel and Adventure Round the Great Lakes. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-25681-3.

- Vail, LeRoy (1991). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07420-0.