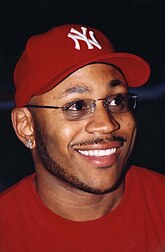

LL Cool J

LL Cool J | |

|---|---|

LL Cool J receiving the 2017 Kennedy Center Honors | |

| Born | James Todd Smith January 14, 1968 |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1984–present |

| Spouse |

Simone Smith (m. 1995) |

| Partner | Kidada Jones (1992–1994)[2] |

| Children | 4[1] |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Queens, New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | Hip hop |

| Discography | LL Cool J discography |

| Labels | |

| Website | llcoolj |

James Todd Smith (born January 14, 1968), known professionally as LL Cool J (short for Ladies Love Cool James),[3] is an American rapper, songwriter, record producer, and actor.[4] He is one of the earliest rappers to achieve commercial success, alongside fellow new school hip hop acts Beastie Boys and Run-DMC.

Signed to Def Jam Recordings in 1984, LL Cool J's breakthrough came with his single "I Need a Beat" and his landmark debut album, Radio (1985). He achieved further commercial and critical success with the albums Bigger and Deffer (1987), Walking with a Panther (1989), Mama Said Knock You Out (1990), Mr. Smith (1995), and Phenomenon (1997). His twelfth album, Exit 13 (2008), was his last in his long-tenured deal with Def Jam.

LL Cool J has appeared in numerous films, including Halloween H20, In Too Deep, Any Given Sunday, Deep Blue Sea, S.W.A.T., Mindhunters, Last Holiday, and Edison. He played NCIS Special Agent Sam Hanna in the CBS crime drama television series NCIS: Los Angeles. LL Cool J was also the host of Lip Sync Battle on Paramount Network.[5][6]

A two-time Grammy Award winner, LL Cool J is known for hip hop songs such as "Going Back to Cali", "I'm Bad", "The Boomin' System", "Rock the Bells", and "Mama Said Knock You Out", as well as R&B hits such as "Doin' It", "I Need Love", "Around the Way Girl" and "Hey Lover". In 2010, VH1 placed him on their "100 Greatest Artists Of All Time" list.[7] In 2017, LL Cool J became the first rapper to receive the Kennedy Center Honors.[8] In 2021, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with an award for Musical Excellence.[9]

Early life and family[edit]

James Todd Smith was born on January 14, 1968, in Bay Shore, New York to Ondrea Griffith (born January 19, 1946) and James Louis Smith Jr,[10] also known as James Nunya.[11][12][13] According to the Chicago Tribune, "[As] a kid growing up middle class and Catholic in Queens, life for Smith was heart-breaking. His father shot his mother and grandfather, nearly killing them both. When 4-year-old Smith found them, blood was everywhere."[14] In 1972, Smith and his mother moved into his grandparents' home in St. Albans, Queens, where he was raised.[15][16] He suffered physical and mental abuse from his mother's ex-boyfriend Roscoe.[14]

Smith began rapping at the age of 10, influenced by the hip-hop group The Treacherous Three. In 1984, sixteen-year-old Smith was creating demo tapes in his grandparents' home.[17] His grandfather, a jazz saxophonist, bought him $2,000 worth of equipment, including two turntables, an audio mixer and an amplifier.[18] During this time, Smith reconciled with his father who "made amends for a lot of things" by offering him guidance at the start of his music career.[14][12][19] His mother was also supportive of his musical endeavors, using her tax refund to buy him a Korg drum machine.[20] Smith has stated that by the time he received musical equipment from his relatives, he "was already a rapper. In this neighborhood, the kids grow up in rap. It's like speaking Spanish if you grow up in an all-Spanish house."[18] This was at the same time that NYU student Rick Rubin and promoter-manager Russell Simmons founded the then-independent Def Jam label. By using the mixer he had received from his grandfather, Smith produced and mixed his own demos and sent them to various record companies throughout New York City, including Def Jam.[18]

Musical career[edit]

In the VH1 documentary Planet Rock: The Story of Hip Hop and the Crack Generation, Smith revealed that he initially called himself J-Ski, but did not want to associate his stage name with the cocaine culture (The rappers who use "Ski" or "Blow" as part of their stage name, e.g., Kurtis Blow and Joeski Love, were associated with the rise of the cocaine culture, as depicted in the 1983 remake of Scarface.) Under his new stage name LL Cool J (an abbreviation for Ladies Love Cool James), coined by his friend and fellow rapper Mikey D,[21][15] Smith was signed by Def Jam, which led to the release of his first official record, the 12-inch single "I Need a Beat" (1984).[17] The single was a hard-hitting, streetwise b-boy song with spare beats and ballistic rhymes.[17] Smith later discussed his search for a label, stating "I sent my demo to many different companies, but it was Def Jam where I found my home."[22] That same year, Smith made his professional debut concert performance at Manhattan Center High School. In a later interview, LL Cool J recalled the experience, stating "They pushed the lunch room tables together and me and my DJ, Cut Creator, started playing. ... As soon as it was over there were girls screaming and asking for autographs. Right then and there I said 'This is what I want to do'."[23] LL's debut single sold over 100,000 copies and helped establish both Def Jam as a label and Smith as a rapper. The commercial success of "I Need a Beat", along with the Beastie Boys' single "Rock Hard" (1984), helped lead Def Jam to a distribution deal with Columbia Records the following year.[24]

1985–1987: Radio[edit]

Radio was released to critical acclaim, both for production innovation and LL's powerful rap.[25] Released November 18, 1985, on Def Jam Recordings in the United States,[26] Radio earned a significant amount of commercial success and sales for a hip hop record at the time. Shortly after its release, the album sold over 500,000 copies in its first five months, eventually selling over 1 million copies by 1988, according to the Recording Industry Association of America.[27][28] Radio peaked at number 6 on the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and at number 46 on the Billboard 200 albums chart.[29] It entered the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart on December 28, 1985, and remained there for 47 weeks, while also entering the Pop Albums chart on January 11, 1986,[29] remaining on that chart for thirty-eight weeks.[29] By 1989, the album had earned platinum status from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), with sales exceeding one million copies; it had previously earned a gold certification in the United States on April 14, 1986.[28] "I Can't Live Without My Radio" and "Rock the Bells" were singles that helped the album go platinum. It eventually reached 1,500,000 copies sold in the US.[30]

With the breakthrough success of his hit single "I Need a Beat" and the Radio LP, LL Cool J became one of the early hip-hop acts to achieve mainstream success along with Kurtis Blow and Run-D.M.C. Gigs at larger venues were offered to LL as he would join the 1986–'87 Raising Hell tour, opening for Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys.[31] Another milestone of LL's popularity was his appearance on American Bandstand as the first hip hop act on the show,[32] as well as an appearance on Diana Ross' 1987 television special, Red Hot Rhythm & Blues.

The album's success also helped in contributing to Rick Rubin's credibility and repertoire as a record producer. Radio, along with Raising Hell (1986) and Licensed to Ill (1986), would form a trilogy of New York City-based, Rubin-helmed albums that helped to diversify hip-hop.[33][34] Rubin's production credit on the back cover reads "REDUCED BY RICK RUBIN", referring to his minimalist production style, which gave the album its stripped-down and gritty sound. This style would serve as one of Rubin's production trademarks and would have a great impact on future hip-hop productions.[35] Rubin's early hip hop production work, before his exit from Def Jam to Los Angeles, helped solidify his legacy as a hip hop pioneer and establish his reputation in the music industry.[35]

1987–1993: Breakthrough and success[edit]

LL Cool J's second album was 1987's Bigger and Deffer, which was produced by DJ Pooh and the L.A. Posse.[36] This stands as one of his biggest-selling career albums, having sold in excess of two million copies in the United States alone.[37] It spent 11 weeks at No. 1 on Billboard's R&B albums chart. It also reached No. 3 on the Billboard's Pop albums chart. The album featured the singles "I'm Bad", the revolutionary "I Need Love" – LL's first #1 R&B and Top 40 hit, "Kanday", "Bristol Hotel", and "Go Cut Creator Go". While Bigger and Deffer, which was a big success, was produced by the L.A. Posse (at the time consisting of Dwayne Simon, Darryl Pierce and, according to himself the most important for crafting the sound of the LP, Bobby "Bobcat" Ervin), Dwayne Simon was the only one left willing to work on producing LL Cool J's third album Walking with a Panther.[38] Released in 1989, the album was a commercial success, with several charting singles ("Going Back to Cali", which had originally been released on the 1987 movie soundtrack Less than Zero, "I'm That Type of Guy", "Big Ole Butt", and "One Shot at Love"). Despite commercial appeal, the album was often criticized by the hip-hop community as being too commercial and materialistic, and for focusing too much on love ballads.[39] As a result, his audience base began to decline due to the album's bold commercial and pop aspirations.[40] According to Billboard, the album peaked at No. 6 on the Billboard 200 and was LL Cool J's second #1 R&B Album where it spent five weeks.

In 1990, LL released Mama Said Knock You Out, his fourth studio album. The Marley Marl produced album received critical acclaim and eventually went double Platinum, selling over two million copies according to the RIAA. Mama Said Knock You Out marked a turning point in LL Cool J's career, as he proved to critics his ability to stay relevant and hard-edged despite the misgivings of his previous album.[40] LL won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Solo Performance in 1992 for the title track. The album's immense success propelled Mama Said Knock You Out to be LL's top selling album of his career (as of 2002) and solidified his status as a hip-hop icon. During this time, LL also recorded a rap solo for Michael Jackson's demo of a song called "Serious Effect" which remains unreleased, but was later leaked online.[40]

1993–2005: Continued success and career prominence[edit]

After acting in The Hard Way and Toys, LL Cool J released 14 Shots to the Dome in March 1993. The album had four singles ("How I'm Comin'", "Back Seat (of My Jeep)", "Pink Cookies in a Plastic Bag Getting Crushed by Buildings", "Stand By Your Man") and guest-featured Lords of the Underground on "NFA-No Frontin' Allowed". That June, the album went gold.

LL Cool J starred in In the House, an NBC sitcom, before releasing his album Mr. Smith (1995), which went on to sell over two million copies. Its singles included "Hey Lover", "Doin' It" and "Loungin". "Hey Lover", featured Boyz II Men, and sampled Michael Jackson's "The Lady in My Life". The song also earned him a Grammy Award. Another song from the album, "I Shot Ya Remix", included debut vocal work by Foxy Brown. In 1996, Def Jam released this "greatest hits" package, offering a good summary of Cool J's career, from the relentless minimalism of early hits such as "Rock the Bells" to the smooth-talking braggadocio that followed. Classic albums including Bigger and Deffer and Mama Said Knock You Out are well represented here. In December 1996, his loose cover of the Rufus and Chaka Khan song "Ain't Nobody" was included on the Beavis and Butt-Head Do America soundtrack & released as a single. LL Cool J's interpretation of "Ain't Nobody" was particularly successful in the United Kingdom, where it topped the UK Singles Chart in early-1997.[41] Later that same year, he released the album Phenomenon. The singles included "Phenomenon" and "Father". The official second single from Phenomenon was "4, 3, 2, 1", which featured Method Man, Redman & Master P and introduced DMX and Canibus.

In 2000, LL Cool J released the album G.O.A.T., which stood for the "Greatest of All Time." It debuted at number one on the Billboard album charts,[42] and went platinum. LL Cool J thanked Canibus in the liner notes of the album, "for the inspiration". LL Cool J's next album 10 from 2002, was his ninth studio (10th overall including his greatest hits compilation All World), and included the singles "Paradise" (featuring Amerie), and the number 1 R&B hit "Luv U Better", produced by the Neptunes. Later pressings of the album added the 2003 Jennifer Lopez duet, "All I Have". The album reached platinum status. LL Cool J's tenth album The DEFinition was released on August 31, 2004. The album debuted at No. 4 on the Billboard charts. Production came from Timbaland, 7 Aurelius, R. Kelly, and others. The lead single was the Timbaland-produced "Headsprung", which peaked at No. 7 on the Hip-Hop and R&B singles chart, and No. 16 on the Billboard Hot 100. The second single was the 7 Aurelius–produced, "Hush", which peaked at No. 14 on the Billboard Hip-Hop and R&B chart and No. 26 on the Hot 100.

2006–2012: Exit 13 and touring[edit]

LL Cool J's 11th album, Todd Smith, was released on April 11, 2006. It includes collaborations with 112, Ginuwine, Juelz Santana, Teairra Mari and Freeway. The first single was the Jermaine Dupri-produced "Control Myself" featuring Jennifer Lopez. They shot the video for "Control Myself" on January 2, 2006, at Sony Studios, New York. The second video, directed by Hype Williams, was "Freeze" featuring Lyfe Jennings.

In July 2006, LL Cool J announced details about his final album with Def Jam Recordings, the only label he has ever been signed to. The album is titled Exit 13. The album was originally scheduled to be executively produced by fellow Queens rapper 50 Cent.[43] Exit 13 was originally slated for a fall 2006 release, however, after a 2-year delay, it was released on September 9, 2008, without 50 Cent as the executive producer. Tracks that the two worked on were leaked to the internet and some of the tracks produced with 50 made it to Exit 13. LL Cool J partnered with DJ Kay Slay to release a mixtape called "The Return of the G.O.A.T.". It was the first mixtape of his 24-year career and includes freestyling by LL Cool J in addition to other rappers giving their renditions of his songs. A track titled "Hi Haterz" was leaked onto the internet on June 1, 2008. The song contains LL Cool J rapping over the instrumental to Maino's "Hi Hater". He toured with Janet Jackson on her Rock Witchu tour, only playing in Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto, and Kansas City.

In September 2009, LL Cool J released a song about the NCIS TV series. It is a single and is available on iTunes. The new track is based on his experiences playing special agent Sam Hanna. "This song is the musical interpretation of what I felt after meeting with NCIS agents, experienced Marines and Navy SEALs," LL Cool J said. "It represents the collective energy in the room. I was so inspired I wrote the song on set."[44]

At South by Southwest in March 2011, LL Cool J was revealed to be Z-Trip's special guest at the Red Bull Thre3Style showcase. This marked the beginning of a creative collaboration between the rap and DJ superstars. The two took part in an interview with Carson Daly where they discussed their partnership.[45] Both artists have promised future collaborations down the road, with LL Cool J calling the duo "organic"[46] One early track to feature LL's talents was Z-Trip's remix of British rock act Kasabian's single "Days Are Forgotten", which was named by influential DJ Zane Lowe as his "Hottest Record In The World"[47] and received a favorable reception in both Belgium and the United Kingdom. In January 2012, the pair released the track "Super Baller" as a free download to celebrate the New York Giants Super Bowl victory. The two have been touring together since 2011, with future dates planned through 2012 and beyond.

2012–present: Authentic, G.O.A.T. 2 and future projects[edit]

On October 6, 2012, LL Cool J released "Ratchet", a new single from his upcoming album titled Authentic Hip-Hop. Following that, on November 3, 2012, LL collaborated with Joe and the production duo Trackmasters on his second single, "Take It".[48]

On February 8, 2013, it was announced that the title of LL's upcoming album would be changed from Authentic Hip-Hop to Authentic, with a new release date of April 30, 2013. A new cover was also unveiled.[49] At around the same time, it was announced that LL Cool J had collaborated with Van Halen guitarist Eddie Van Halen on two tracks on the album.[50][51][52]

On October 16, 2013, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame announced LL Cool J as a nominee for inclusion in 2014.[53] In October 2014, LL announced that his 14th studio album would be called G.O.A.T. 2 and would be released in 2015.[54] LL stated that "the concept behind the album was to give upcoming artists an opportunity to shine, and put myself in the position where I have to spit bars with some of the hardest rhymers in the game"; however, the album was put on hold. LL Cool J explained the reason for it, saying, "It was good but I didn't feel like it was ready yet."[55]

On January 21, 2016, LL received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[56]

In March 2016, LL announced his retirement on social media, but quickly walked back his announcement and indicated that a new album was on the way.[57] LL hosted the Grammy Awards Show for five consecutive years, from the 54th Grammy Awards on February 12, 2012, through the 58th Grammy Awards on February 15, 2016.[58]

In October 2018, LL Cool J was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[59] In September 2019, it was announced that LL had re-signed to Def Jam for future album releases.[60] His upcoming album will be produced by Q-Tip.[61]

On December 29, 2021, LL Cool J canceled his performance at Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2022 after testing positive for COVID-19.[62]

LL hosted the 2022 iHeartRadio Music Awards on March 22, 2022.[63][64]

Acting career[edit]

While LL Cool J first appeared as a rapper in the movie Krush Groove (performing "I Can't Live Without My Radio"),[65] his first acting part was a small role in a high school football movie called Wildcats.[66] He landed the role of Captain Patrick Zevo in Barry Levinson's 1992 film Toys.[67] From 1995 to 1999, he starred in his own television sitcom In the House. He portrayed an ex-Oakland Raiders running back who finds himself in financial difficulties and is forced to rent part of his home out to a single mother and her two children, one of whom moves out with her before the third season.[68]

In 1998, LL Cool J played security guard Ronny in Halloween H20, the seventh movie in the Halloween franchise.[69] In 1999, he co-starred as Preacher, the chef in the Renny Harlin horror/comedy Deep Blue Sea.[70] He received positive reviews for his role as Dwayne Gittens, an underworld boss nicknamed "God", in In Too Deep.[71] Later that year, he starred as Julian Washington—a talented but selfish running back on fictional professional football team the Miami Sharks—in Oliver Stone's drama Any Given Sunday. He and co-star Jamie Foxx allegedly got into a real fistfight while filming a fight scene.[72] During the next two years, LL Cool J appeared in Rollerball,[73] Deliver Us from Eva,[74] S.W.A.T.,[75] and Mindhunters.[76]

In 2005, he returned to television in a guest-starring role on the Fox medical drama House; he portrayed a death row inmate felled by an unknown disease in an episode titled "Acceptance". He appeared as Queen Latifah's love interest in the 2006 movie Last Holiday.[77] He also guest-starred on 30 Rock in the 2007 episode "The Source Awards", portraying a hip-hop producer called Ridikulous who Tracy Jordan fears may kill him.[78] LL Cool J appeared in Sesame Street's 39th season, introducing the word of the day--"Unanimous"—in episode 4169 (September 22, 2008) and performing "The Addition Expedition" in episode 4172 (September 30, 2008).[79]

In 2009, he began starring on the CBS police procedural NCIS: Los Angeles. The show ran for 14 seasons and is a spin-off of NCIS, which itself is a spin-off of the naval legal drama JAG. LL Cool J portrayed NCIS Special Agent Sam Hanna, an ex–Navy SEAL who is fluent in Arabic and is an expert on West Asian culture. The series debuted in autumn of 2009, but the characters were introduced in an April 2009 crossover episode on the parent show.[80][81] In 2013, LL received a Teen Choice Award for Choice TV Actor: Action for his work on the program.[82] In May 2023, following the series finale of NCIS: Los Angeles, it was announced that LL would reprise the role of Sam Hanna as a recurring guest star in the third season of NCIS: Hawaiʻi.[83]

In December 2013, LL co-starred as a gym owner in the sports dramedy Grudge Match.[84] From 2015 to 2019, LL hosted the show Lip Sync Battle.[85] He was also cast to play Beth's father in Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising, as shown in a trailer for the film, but his scenes were cut from the final product.[86]

Other ventures[edit]

LL Cool J worked behind the scenes with the mid-1980s hip-hop sportswear line TROOP.[87] He also launched a clothing line (called "Todd Smith").[88] The brand produced popular urban apparel. Designs included influences from LL's lyrics and tattoos, as well as from other icons in the hip-hop community.[89] LL Cool J has written four books, including I Make My Own Rules, (1997), an autobiography cowritten with Karen Hunter. His second book was the children-oriented book called And The Winner Is... published in 2002. In 2006, LL Cool J and his personal trainer, Dave "Scooter" Honig, wrote a fitness book titled The Platinum Workout. His fourth book, LL Cool J (Hip-Hop Stars) was cowritten in 2007 with hip-hop historian Dustin Shekell and Public Enemy's Chuck D.

Throughout his career, LL Cool J has started several businesses in the music industry. In 1993, he founded a music label called P.O.G. (Power Of God) and formed the company Rock The Bells to produce music. On his Rock The Bells label, he had artists such as AMyth,[90] Smokeman, Natice, Chantel Jones and Simone Starks. Additionally, Rock the Bells Records was responsible for the Deep Blue Sea soundtrack, which helped to promote the 1999 movie of the same name. Rufus "Scola" Waller also signed to the label, but was ultimately released when the label folded.[91] LL Cool J founded and launched Boomdizzle.com, a record label / social networking site, in September 2008. The website was designed to accept music uploads from aspiring artists, primarily from the hip-hop genre, and allow the site's users to rate songs through contests, voting, and other community events.[92]

In March 2015, LL Cool J appeared in an introduction to WrestleMania 31.[93]

Legacy[edit]

With the breakthrough success of his hit single "I Need a Beat" and the Radio LP, LL Cool J became one of the first hip-hop acts to achieve mainstream success, along with Kurtis Blow and Run-DMC. Gigs at larger venues were offered to LL as he would join the 1986–'87 Raising Hell tour, opening for Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys.[31] Another milestone of LL's popularity was his appearance on American Bandstand as the first hip-hop act on the show.[32]

The album's success also helped in contributing to Rick Rubin's credibility and repertoire as a record producer. Radio, along with Raising Hell (1986) and Licensed to Ill (1986), would form a trilogy of New York City-based, Rubin-helmed albums that helped to diversify hip-hop.[33][34] Rubin's production credit on the back cover reads "REDUCED BY RICK RUBIN", referring to his minimalist production style, which gave the album its stripped-down and gritty sound. This style would serve as one of Rubin's production trademarks and would have a great impact on future hip-hop productions.[35] Rubin's early hip hop production work, before his exit from Def Jam to Los Angeles, helped solidify his legacy as a hip hop pioneer and establish his reputation in the music industry.[35]

Radio's release coincided with the growing new school scene and subculture, which also marked the beginning of hip-hop's "golden age" and the replacement of old school hip hop.[94] This period of hip hop was marked by the end of the disco rap stylings of old school, which had flourished prior to the mid-1980s, and the rise of a new style featuring "ghetto blasters". Radio served as one of the earliest records, along with Run-D.M.C.'s debut album, to combine the vocal approach of hip hop and rapping with the musical arrangements and riffing sound of rock music, pioneering the rap rock hybrid sound.[95]

The emerging new-school scene was initially characterized by drum machine-led minimalism, often tinged with elements of rock, as well as boasts about rapping delivered in an aggressive, self-assertive style. In image as in song, the artists projected a tough, cool, street b-boy attitude. These elements contrasted sharply with the 1970s P-Funk and disco-influenced outfits, live bands, synthesizers and party rhymes of acts prevalent in 1984, rendering them old school.[96] In contrast to the lengthy, jam-like form predominant throughout early hip hop ("King Tim III", "Rapper's Delight", "The Breaks"), new-school artists tended to compose shorter songs that would be more accessible and had potential for radio play, and conceived more cohesive LPs than their old-school counterparts; the style typified by LL Cool J's Radio.[97] A leading example of the new school sound is the song "I Can't Live Without My Radio", a loud, defiant declaration of public loyalty to his boom box, which The New York Times described as "quintessential rap in its directness, immediacy and assertion of self".[18] It was featured in the film Krush Groove (1985), which was based on the rise of Def Jam and new school acts such as Run-D.M.C. and the Fat Boys.[98]

The energy and hardcore delivery and musical style of rapping featured on Radio, as well as other new-school recordings by artists such as Run-D.M.C., Schooly D, T La Rock and Steady B, proved to be influential to hip-hop acts of the "golden age" such as Boogie Down Productions and Public Enemy.[99] The decline of the old-school form of hip hop also led to the closing of Sugar Hill Records, one of the labels that helped contribute to early hip hop and that, coincidentally, rejected LL's demo tape.[100] As the album served as an example of an expansion of hip-hop music's artistic possibilities, its commercial success and distinct sound soon led to an increase in multi-racial audiences and listeners, adding to the legacy of the album and hip hop as well.[95][101]

In 2017, LL Cool J became the first rapper to receive Kennedy Center Honors.[8]

In 2021, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with an award for Musical Excellence.[9]

Personal life[edit]

Relationships[edit]

Smith dated Kidada Jones, daughter of producer Quincy Jones, from 1992 to 1994.[102]

Marriage[edit]

He married Simone Johnson in 1995.[11] The couple met in 1987 and have four children.[103]

Simone Johnson-Smith was diagnosed with chondrosarcoma, a third-stage bone cancer, and was later cancer-free as of 2004.[104][105][106] She became an entrepreneur, launching a jewelry line in 2011, before becoming a born-again Christian.[citation needed]

Smith is credited for introducing his wife to singer and close friend, Mary J. Blige, in 2005 and inspiring their friendship; both women launched another jewelry line, Sister Love, in late 2020 after announcing it two years prior.[107][108][109]

In 2023, the couple co-founded a jewelry line for men, Majesty.[110]

Ancestry[edit]

In an episode of Finding Your Roots, Smith learned that his mother was adopted by Eugene Griffith and Ellen Hightower. The series' genetic genealogist CeCe Moore identified Smith's biological grandparents as Ethel Mae Jolly and Nathaniel Christy Lewis through analysis of his DNA. Smith's biological great-uncle was Hall of Fame boxer John Henry Lewis.[10]

Political involvement[edit]

In 2002, LL Cool J supported George Pataki's bid for a third term as Governor of New York.[111] In 2003, LL Cool J spoke at a U.S. Senate Committee hearing on the RIAA lawsuits against Americans distributing or downloading copyrighted music over peer-to-peer networks. He appeared to endorse the RIAA's position, claiming illegal file sharing was hurting his sales and that his session musicians "can't live" due to the lost income. Chuck D provided an opposing viewpoint, saying free file-sharing could be leveraged as a promotional tool and the industry was being overprotective of its copyright.[112] LL also voiced his support for New York State Senator Malcolm Smith, a Democrat, during an appearance on the senator's local television show;[113] LL worked with Smith in putting on the annual Jump and Ball Tournament in the rapper's childhood neighborhood of St. Albans, Queens.[114] In a February 10, 2012 televised interview with CNN host Piers Morgan, LL Cool J expressed sympathy for President Barack Obama and ascribed negative impressions of his leadership to Republican obstruction designed to "make it look like you have a coordination problem." He was quick to add that no one "should assume that I'm a Democrat either. I'm an independent, you know?"[115] In his 2010 book LL Cool J's Platinum 360 Diet and Lifestyle, he included Obama in a list of people he admired, stating that the then-president had "accomplished what people thought was impossible."[116]

Philanthropy[edit]

LL Cool J has his own charitable foundation called Jump & Ball, which is based in his hometown of Queens, New York, and offers an athletic and team-building program for young people. He is also involved in many charitable causes for literacy, music, and arts programs for kids and schools.[117]

Discography[edit]

- Studio albums

- Radio (1985)

- Bigger and Deffer (1987)

- Walking with a Panther (1989)

- Mama Said Knock You Out (1990)

- 14 Shots to the Dome (1993)

- Mr. Smith (1995)

- Phenomenon (1997)

- G.O.A.T. (2000)

- 10 (2002)

- The DEFinition (2004)

- Todd Smith (2006)

- Exit 13 (2008)

- Authentic (2013)

Filmography[edit]

Film[edit]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Krush Groove | Himself | |

| 1986 | Wildcats | Rapper | |

| 1991 | The Hard Way | Detective Billy | |

| 1992 | Toys | Captain Patrick Zevo | |

| 1995 | Out-of-Sync | Jason St. Julian | |

| Eyes on Hip Hop | Rapper | Video | |

| 1996 | The Right to Remain Silent | Charles Red Taylor | TV movie |

| 1997 | Touch | Himself | |

| B*A*P*S | Himself | ||

| 1998 | Caught Up | Roger | |

| Woo | Darryl | ||

| Halloween H20: 20 Years Later | Ronny Jones | ||

| 1999 | Deep Blue Sea | Sherman "Preacher" Dudley | |

| In Too Deep | Dwayne Keith "God" Gittens | ||

| Any Given Sunday | Julian "J-Man" Washington | ||

| 2000 | Charlie's Angels | Mr. Jones | |

| 2001 | Kingdom Come | Ray Bud Slocumb | |

| 2002 | Rollerball | Marcus Ridley | |

| 2003 | Deliver Us from Eva | Ray Adams | |

| S.W.A.T. | Officer Deacon "Deke" Kaye | ||

| 2004 | Mindhunters | Gabe Jensen | |

| 2005 | Edison | Officer Rafe Deed | |

| Slow Burn | Luther Pinks | ||

| 2006 | Last Holiday | Sean Williams | |

| 2007 | The Man | Manny Baxter | TV movie |

| 2008 | The Deal | Bobby Mason | |

| Drillbit Taylor | Himself | ||

| 2013 | Grudge Match | Frankie Brite | |

| 2023 | A.k.a. Mr. Chow | Himself |

Television[edit]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986–1989 | American Bandstand | Himself/Musical Guest | Recurring Guest |

| 1986–1996 | Soul Train | Himself/Musical Guest | Recurring Guest |

| 1987–1998 | Showtime at the Apollo | Himself/Musical Guest | Recurring Guest |

| 1987 | Saturday Night Live | Himself/Musical Guest | Episode: "Sean Penn/L.L. Cool J/The Pull" |

| 1988 | Remote Control | Himself | Episode: "MTV Celebrity Episode" |

| 1991 | MTV Unplugged | Himself | Episode: "Yo! MTV Rap Unglugged" |

| In Living Color | Himself/Musical Guest | Episode: "Anton and the Reporter" | |

| 1994 | The Adventures of Pete & Pete | Mr. Throneberry | Episode: "Sick Day" |

| 1995 | Wheel of Fortune | Himself/Celebrity Contestant | Episode: "Celebrity Award Winners: Game 3" |

| 1995–1999 | In the House | Marion Hill | Main Cast |

| 1995–2004 | Mad TV | Himself | Recurring Guest |

| 1996 | All That | Himself/Musical Guest | Episode: "Tia & Tamera Mowry/LL Cool J" |

| 1996–1997 | Soul Train Music Awards | Himself/Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| 1997 | Beavis and Butt-Head | Himself | Episode: "Beavis and Butt-Head Do Thanksgiving" |

| 1998 | Soul Train Lady of Soul Awards | Himself/Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| Oz | Jiggy Walker | Episode: "Strange Bedfellows" | |

| 1999–2000 | Making the Video | Himself/Musical Guest | 2 episodes |

| 2000 | Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards | Himself/Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| Behind the Music | Himself | Episode: "Run-DMC" | |

| 2001 | American Music Awards | Himself/Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| The Challenge | Himself | Episode: "Rollerball Resurrection" | |

| Intimate Portrait | Himself | Episode: "Kim Fields" | |

| 2002 | WWE SmackDown | Himself | Episode: "Entertainment Meets Sports Entertainment" |

| 2003–2004 | Top of the Pops | Himself/Musical Guest | Recurring Guest |

| 2004 | American Casino | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J Concert" |

| Behind the Music | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J" | |

| 2005 | American Idol | Himself/Guest Judge | Episode: "Auditions: Cleveland & Orlando" |

| House | Clarence | Episode: "Acceptance" | |

| 2006 | E! True Hollywood Story | Himself | Episode: "Hip Hop Wifes" |

| Biography | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J" | |

| 2007 | NAACP Image Awards | Himself/Host | Main Host |

| 30 Rock | Ridikolus | Episode: "The Source Awards" | |

| 2008 | So You Think You Can Dance | Himself/Musical Guest | Episode: "Results Show: Two Dancers Eliminated" |

| Sesame Street | Himself | Episode: "Telly the Tiebreaker" | |

| Project Runway | Himself/Guest Judge | Episode: "Rock N' Runway" | |

| The Greatest | Himself | Episode: "100 Greatest Hip Hop Songs" | |

| 2009 | Fashion Police | Himself/Host | Episode: "The 2009 Grammy Awards" |

| Kathy Griffin: My Life on the D-List | Himself | Episode: "I Heart Lily Tomlin" | |

| WWII in HD | Shelby Westbrook (voice) [118] | Episode: "Striking Distance" | |

| 2009, 2023 | NCIS | Special Agent Sam Hanna | 3 episodes |

| 2009–2023 | NCIS: Los Angeles | Special Agent Sam Hanna | Main Cast |

| 2010 | The Electric Company | Himself | 2 episodes |

| 2012 | Bizarre Foods America | Himself | Episode: "Las Vegas" |

| Hawaii Five-0 | Special Agent Sam Hanna | Episode: "Pa Make Loa" | |

| 2012–2016 | Grammy Awards | Himself/Host | Main Host |

| 2014 | Foo Fighters: Sonic Highways | Himself | Episode: "New York" |

| 2015 | In Their Own Words | Himself | Episode: "Muhammad Ali" |

| 2015–2019 | Lip Sync Battle | Himself/Host | Main Host |

| 2016 | Finding Your Roots | Himself | Episode: "Family Reunions" |

| Greatest Hits | Himself | Episode: "Greatest Hits: 1995–2000" | |

| Hip-Hop Evolution | Himself | Main Guest: Season 1 | |

| 2017 | Pyramid | Himself/Celebrity Player | Episode: "Leslie Jones vs. LL Cool J and Tom Bergeron vs. Jennifer Nettles" |

| Oprah's Master Class | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J" | |

| Martha & Snoop's Potluck Dinner Party | Himself | Episode: "Let's Get Roasted" | |

| American Dad! | Special Agent Sam Hanna (voice) | Episode: "Casino Normale" | |

| 2018 | Story of Cool | Himself/Narrator | Main Narrator |

| Shut Up and Dribble | Himself | Episode: "102" | |

| 2019 | Shangri-La | Himself | 2 episodes |

| Kennedy Center Honors | Himself/Host | Main Host | |

| 2021 | Hip Hop Uncovered | Himself | Episode: "Victory Lap" |

| 2022 | iHeartRadio Music Awards | Himself/Host | Main Host |

| They Call Me Magic | Himself | Episode: "Magic" | |

| Supreme Team | Himself | Main Guest | |

| 2023 | Fight the Power: How Hip-Hop Changed the World | Himself | 2 episodes |

| America in Black | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J, Black Land Reparations and The Shade Room" | |

| Superfan | Himself | Episode: "LL Cool J" | |

| Hip Hop Treasures | Himself | 2 episodes | |

| 2023–2024 | NCIS: Hawai'i | Special Agent Sam Hanna | 7 episodes |

Documentary[edit]

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1986 | Big Fun in the Big Town |

| 1990 | RapMania: The Roots of Rap |

| 1991 | Desperately Seeking Roger |

| 1995 | The Show |

| 2021 | Mary J. Blige's My Life |

Awards and nominations[edit]

Grammy Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | "Going Back To Cali" | Best Rap Performance | Nominated | [119] |

| 1992 | "Mama Said Knock You Out" | Best Rap Solo Performance | Won | [120] |

| 1993 | "Strictly Business" | Nominated | [121] | |

| 1994 | "Stand By Your Man" | Nominated | [122] | |

| 1997 | "Hey Lover" | Won | [123] | |

| 1997 | Mr. Smith | Best Rap Album | Nominated | [123] |

| 1998 | "Ain't Nobody" | Best Rap Solo Performance | Nominated | [124] |

| 2004 | "Luv U Better" | Best Rap/Sung Collaboration | Nominated | [125] |

| 2005 | The DEFinition | Best Rap Album | Nominated | [126] |

American Music Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Bigger & Deffer | Favorite R&B/Soul Album | Nominated |

| 1988 | LL Cool J | Favorite R&B/Soul Male Artist | Nominated |

| 1992 | LL Cool J | Favorite R&B/Soul Male Artist | Nominated |

Billboard Music Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | LL Cool J | #1 Rap Singles Artist | Won |

| 1996 | LL Cool J | Rap Artist of the Year | Won |

MTV Video Music Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | "Mama Said Knock You Out" | Best Rap Video | Won | [128] |

| Best Cinematography in a Video | Nominated | [128] | ||

| 1996 | "Doin' It" | Best Rap Video | Nominated | [129] |

| 1997 | Lifetime Achievement | Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award | Won | [130] |

NAACP Image Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated Work | Category | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Mr. Smith | Best Rap Artist | Won | [131] |

| 1997 | Phenomenon | Best Rap Artist | Won | |

| 2001 | G.O.A.T. | Outstanding Hip-Hop/Rap Artist | Won | [132] |

| 2003 | 10 | Outstanding Male Artist | Won | [133] |

Soul Train Music Awards[edit]

| Year | Nominated Work | Category | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Radio | Best Rap Album | Nominated | [citation needed] |

| 1988 | Bigger and Deffer | Best Rap Album | Won | [citation needed] |

| "I Need Love" | Best Rap Single | Won | [134] | |

| 1991 | Mama Said Knock You Out | Best Rap Album | Nominated | [citation needed] |

| 2003 | 10 | Best R&B/Soul or Rap Album of the Year | Nominated | [135] |

| Outstanding Career Achievements in the Field of Entertainment | Quincy Jones Award | Won | [136] | |

| 2005 | "Headsprung" | Best R&B/Soul or Rap Dance Cut | Nominated | [137] |

Other honors and awards[edit]

- 1988 – Enstooled as Kwasi Achi-Bru, a chieftain of the Akan people, in Abidjan, Ivory Coast[138]

- 1991 – Billboard Top Rap Singles Artist[139]

- 1997 – Patrick Lippert Award, Rock The Vote[140]

- 2003 – Source Foundation Image Award, for "his community work"

- 2007 – Long Island Music Hall of Fame, Inducted as part of the Inaugural Class of Inductees for his contribution to Long Island's rich musical heritage[141]

- 2011 – BET Hip Hop Awards, Honored with the I Am Hip Hop Award for his contributions to hip-hop culture[142]

- 2013 – A New York City double decker tour bus was dedicated to LL Cool J and his life's work[143]

- 2014 – Honorary Doctor of Arts, Northeastern University, for his contributions to hip-hop culture[144]

- 2016 – LL Cool J was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk Of Fame.[145]

- 2017 – first hip hop artist to receive a Kennedy Center Honor

- LL Cool J has been nominated six times for induction into The Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame. He has been nominated in 2010, 2011, 2014, 2018, 2019, and 2021 as a performer.[146] In 2021, He was inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame with an award for Musical Excellence.[9]

- 2022 – Honored with the Key of the City of New York in the Queens borough[147][148][149]

Acting[edit]

| Year | Award | Category | Work | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series | In the House | Nominated | [131] |

| 1997 | Kids' Choice Awards | Favorite Television Actor | Nominated | [citation needed] | |

| 1998 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series | Nominated | [citation needed] | |

| 2000 | Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Deep Blue Sea | Nominated | [150] | |

| Blockbuster Entertainment Award | Favorite Supporting Actor – Action | Won | [151] | ||

| 2004 | Black Reel Awards | Best Actor | Deliver Us from Eva | Nominated | [152] |

| 2006 | Teen Choice Awards | Award for Choice Movie: Liplock (shared with Queen Latifah) | Last Holiday | Nominated | [citation needed] |

| 2011 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | NCIS: Los Angeles | Won | [153] |

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice TV Actor: Action | Nominated | [154] | ||

| 2012 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | Won | [155] | |

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice TV Actor: Action | Nominated | [156] | ||

| Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Special Class Programs | The 54th Annual Grammy Awards | Nominated | [157] | |

| 2013 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | NCIS: Los Angeles | Won | [158] |

| Teen Choice Awards | Choice TV Actor: Action | Won | [159] | ||

| 2014 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | Won | [160] | |

| Prism Awards | Male Performance in a Drama Series Multi-Episode Storyline | Nominated | [161] | ||

| 2015 | NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | Nominated | [162] | |

| 2016 | Outstanding Actor in a Drama Series | Nominated | [163] | ||

| Primetime Emmy Awards | Outstanding Structured Reality Program | Lip Sync Battle | Nominated | [164] | |

| People's Choice Awards | Favorite TV Crime Drama Actor | NCIS: Los Angeles | Nominated | [165] | |

| 2017 | Favorite TV Crime Drama Actor | Nominated | [166] |

References[edit]

- ^ a b Eve Crosbie (March 21, 2021). "Meet NCIS: Los Angeles star LL Cool J's family". Hello.

- ^ J, LL Cool; Hunter, Karen (1998). I Make My Own Rules. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-312-17110-0.

- ^ CBS (September 12, 2008). "There's No Doubt 'Ladies Love Cool James'". CBS News. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ Farber, Jim (October 24, 2010). "Your nabe: A guide to the hip hop haven of Hollis, Queens". NY Daily News. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ baseballproo77 (April 2, 2015). "Lip Sync Battle (TV Series 2015–)". IMDb.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Lip Sync Battle | Paramount Network". paramountnetwork.com.

- ^ "VH1 100 Greatest Artists Of All Time". Stereogum. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Carmichael, Rodney (August 3, 2017). "LL Cool J to Become Kennedy Center's First Hip-Hop Honoree". NPR.

- ^ a b c "Tina Turner, Jay-Z, Foo Fighters Among Those Inducted Into Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame". NPR. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Finding Your Roots. Season 3. Episode 27. February 16, 2016. Public Broadcasting Station.

- ^ a b Schneider, Karen (February 13, 2003). "Hip Pop". People. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "RIP to My Father James Nunya. You passed away yesterday. But The lessons you taught me live on in my heart. Thank you. I love you". Twitter.com. September 27, 2012.

- ^ "LL Cool J forgives dad for shooting mother". Hollywood.com. January 28, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c Wiltz, Teresa (September 19, 1997). "Rapper Ll Cool J Puts Wild Days, Demons Behind Him". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Hess, Mickey (2009). Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 59. ISBN 0-31334-321-7.

- ^ "Southeastern Queens: Saint Albans". QNSMADE. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021..

- ^ a b c "MTV.com – LL Cool J Bio". MTV Networks. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Holden, Stephen. "From Rock To Rap" Archived December 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, April 26, 1987. Retrieved on November 16, 2008.

- ^ "LL Cool J Revealed in 1997 Memoir That His Dad Shot His Mom, Grandfather". eurweb.com. September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ Danielle Harling (January 21, 2014). "LL Cool J Says His Mother's Tax Refund Funded His Demo". Hiphopdx.com.

I sent demo after demo into every record company. And I got rejection letters from company after company. And I just kept at it. And then what actually happened is I quit and my mother got her tax return. And she took her tax return and bought me some equipment because she knew I was depressed and I was down in the dumps because I didn't have the proper equipment to make what I felt was a good demo. So, she took her whole tax return bought me a drum machine. It was a Korg actually. And me and my man Frankie we went in the basement, we didn't even read the instructions. We played it manually.

- ^ "Acronyms and abbreviations by the Free Online Dictionary". Farlex, Inc. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Def Jam Recordings – LL Cool J Biography". The Island Def Jam Music Group. Archived from the original on April 29, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ "LL Cool J bio: Edison Force ActorTribute.ca..." Tribute Entertainment Media Group. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "Address Island / Def Jam Records ... Def Jam history". GoDaddy.com, Inc. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ Hirschberg, Lynn (September 2, 2007). "The Music Man". New York Times Magazine.

- ^ "LL Cool J career discography at HeadSprung.net". Headsprung.net. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ George (2000), pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b "RIAA searchable database". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Billboard Music Charts – Search Results – LL Cool J Radio". Billboard. Retrieved August 4, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Chris Harris (April 19, 2006). "LL Cool J Can't Knock Out Billboard Champs". MTV.

- ^ a b "Biography and other information at Askmen.com". IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "Career overview at McgillisMusic". World Wide Entertainment USA, Inc. Archived from the original on April 12, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b "Radio cd product notes". Muze Inc. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ a b "Kurtis Blow Presents: The History Of Rap, Vol. 1: The Genesis". Rhino Entertainment. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "About.com ... Rick Rubin's Style and Approach". Archived from the original on January 23, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "DJ Pooh | Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "US Certifications". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ The Rap Talk Crew. "A historic sit-down with Bobcat". Rap Talk Magazine. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Walking with a Panther: Review". AllMusic. Retrieved December 23, 2009.

- ^ a b c All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books. 2002. p. 664. ISBN 087930653X.

- ^ "Beavis and Butt-Head Do America – Original Soundtrack". Allmusic.com.

- ^ "Biography – LL Cool J". Billboard. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Moss, Corey (July 5, 2006). "50 Cent, LL Cool J Teaming Up For LP – News Story Music, Celebrity, Artist News | MTV News". Mtv. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Adam Bryant (September 16, 2010). "VIDEO: Check out LL Cool J's New NCIS:LA-Inspired Song". TV Guide. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Daly, Carson. "Last Call". NBC. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ Freedman, Pete (March 20, 2011). "SXSW Interview: LL Cool J and Z-Trip Talk About Their Collaboration, Their High Esteem For The Hip-Hop "Blueprint" and Their Thoughts On Rap's Up-And-Coming Talent". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Lowe, Zane. "Hottest Record – Kasabian – Days Are Forgotten (LL Cool J Remix)". BBC. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "LL Cool J – Take It ft. Joe". Youtube.

- ^ Horowitz, Steven J. (February 14, 2013). "LL Cool J Announces "Authentic" Release Date & Tracklist". HipHopdx.com. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "LL Cool J On Eddie Van Halen Collabo: "Now He's Officially Done Hip-Hop"". Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Eddie Van Halen Teams Up With LL Cool J". April 2, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Hear Eddie Van Halen Perform on Two New LL Cool J Songs". Ultimate Classic Rock. May 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ "Nirvana, Kiss, Hall and Oates Nominated for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame" Archived September 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- ^ "LL Cool J On Def Jam's 30th Anniversary And His New Street Album". XXL Mag. October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Unretired Rap Legend LL Cool J Shares New Album Details & Offers 'G.O.A.T. 2' Update". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 19, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ "LL COOL J Gets a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". CBS. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "LL Cool J retires, unretires, then announces new album". CNN. March 15, 2016. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ "Grammys: LL Cool J Back for Fifth Year as Host". Hollywood Reporter. December 16, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Class of 2019 Nominees". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Def Jam Records Re-Signs LL Cool J To Iconic Label". Allhiphop.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ Lamarre, Carl. "Q-Tip Reacts to Rock Hall Nomination: 'Music's Evolution Can't Happen Without Hip-Hop Artists'". Billboard. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Mamo, Heran (December 29, 2021). "LL Cool J Cancels 'New Year's Rockin' Eve' Performance After Testing Positive for COVID-19". Billboard. Retrieved December 29, 2021.

- ^ Grein, Paul (February 24, 2022). "LL Cool J Set to Host 2022 iHeartRadio Music Awards". Billboard. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Carter, Justin (March 22, 2022). "How to Watch iHeartRadio Music Awards". How to Watch and Stream Major League & College Sports – Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "LL Cool J's Journey From 'Krush Groove' To The Grammys". MTV. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Movie review : 'Wildcats' doesn't put points on scoreboard". L.A. Times. February 13, 1986. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "The Military Industrial Toy Chest: Barry Levinson's Toys at 25". Consequence of Sound. December 17, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "LL Cool J's Defense : With the Rapper 'In the House,' His Street Rep Is on the Line". L.A. Times. March 21, 1996. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Gelder, Lawrence Van (August 5, 1998). "FILM REVIEW; Monster and Victim: Older, Not Wiser". The New York Times.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (July 28, 1999). "FILM REVIEW; Superjaws: Lab Sharks Turn Men Into Sushi". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "'In Too Deep': The Charisma of Human Evil". Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "LL Cool J, Jamie Foxx Exchange Blows On Set Of Oliver Stone Football Flick". MTV.

- ^ Simmons, Bill. "Dropping the 'Rollerball'". ESPN. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (February 7, 2003). "FILM REVIEW; Dreaming Up a Riddle for a Know-It-All". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (August 8, 2003). "FILM REVIEW; Working Up A S.W.E.A.T." The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Mindhunters movie review & film summary". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (January 13, 2006). "From Bad News Springs a Newfound Joie de Vivre". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Why you should revisit '30 Rock' this St. Patrick's Day". Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "See What Happens When Rappers Visit Sesame Street". IFC. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Bierly, Mandi (February 25, 2009). "'NCIS' spinoff officially lands LL Cool J". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ "There's something familiar about 'NCIS: Los Angeles'". Newsday. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Complete list of Teen Choice 2013 Awards winners". Los Angeles Times. August 12, 2013.

- ^ Cordero, Rosy (May 22, 2023). "LL Cool J Joins Cast Of 'NCIS: Hawai'i' Season 3 Reprising Sam Hanna Role". Deadline.com. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ "In Grudge Match, Not Quite Rocky Balboa Against Raging Bull". The Village Voice. December 24, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "LL Cool J to Host Spike's 'Lip Sync Battle' for EP Jimmy Fallon". Hollywood Reporter. January 7, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Stephanie Merry (May 23, 2016). "Jokes from the 'Neighbors 2' trailer aren't in the movie. Should we be angry?". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 1330888409.

- ^ "Allhiphop". AllHipHop.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ "Todd Smith by LL Cool J". Toddsmithny.com. December 29, 2010. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "LL Cool J Todd Smith Clothing Collection Launch and Video". Celebrity Clothing Line. March 14, 2008. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2000). Top Pop Singles 1955–1999. Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research, Inc. p. 13. ISBN 0-89820-139-X.

- ^ "SCOLA". Music.blackplanet.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Press Release". Boomdizzle.com. July 15, 2008. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Here's LL Cool J's Emotional Opening To WrestleMania 31". Uproxx. March 29, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Encyclopedia – Britannica Online Encyclopedia ... Def Jam, LL, & new school hip hop". 2008 Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ a b Yahoo! Music: Radio Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Yahoo! Inc. Retrieved on November 16, 2008.

- ^ Toop (2000), p. 126.

- ^ Shapiro (2005), p. 228.

- ^ "CaseNet.com – LL Cool J". CaseNet. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ Coleman (2007), p. 354.

- ^ "LL Cool J :: Radio ** RapReviews "Back to the Lab" series ** by Steve "Flash" Juon". RapReviews.com. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ EntertainmentSimone Smith, LL Cool J's Wife: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know Archived April 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, heavy.com April 22, 2015

- ^ LL Cool J (1997). I Make My Own Rules. New York, NY : St. Martin's Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-312-17110-0.

- ^ Weigle, Lauren (December 26, 2017). "LL Cool J's Kids With Wife Simone Smith". Heavy.com. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ "LL Cool J on How Wife Simone's Battle With Cancer Inspired Activism". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "LL Cool J and His Wife Simone Smith Team Up For The Beat Cancer Like A Boss Campaign". Essence. October 23, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ Marie, Erika (April 19, 2019). "LL Cool J & Wife Simone Share Details Of Her Fight With Rare Bone Cancer". HotNewHipHop. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "Who Is LL Cool J's Wife? All About Simone I. Smith". Peoplemag. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "Mary J. Blige Teams Up with LL Cool J's Wife for Jewelry Collaboration". EBONY. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "Mary J. Blige and Simone Smith Launch Jewelry Line 'Sister Love' Exclusively at Essence Festival". Essence. October 23, 2020. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ Palmieri, Jean E. (May 15, 2023). "Simone Smith to Launch Higher-priced Men's Jewelry Line Under Majesty Name". WWD. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ Katz, Celeste (September 27, 2002). "Cool J comes out for Pataki". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Dean, Katie (October 1, 2003). "Rappers in Disharmony on P2P". Wired. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Senator Malcolm Smith Show w. LL Cool J part 3". YouTube. January 2, 2008. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "One On 1: Hip-Hop Artist LL Cool J Leaves Footprints Beyond Music". NY1.com. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "CNN – Transcripts". Transcripts.cnn.com. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ LL Cool J with Dave Honig, Chris Palmer & Jim Stoppani; LL Cool J's Platinum 360 Diet and Lifestyle: A Full-Circle Guide to Developing Your Mind, Body, and Soul, page 14, Rodale, 2010

- ^ "LL Cool J: 2018 We are Family Humanitarian Award honoree". www.wearefamily.org. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "WWII in HD DVD Set | WW2 HD DVD – History Channel". Shop.history.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Rock On The Net: 31st Annual Grammy Awards – 1989". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Rock On The Net: 34th Annual Grammy Awards – 1992". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Rock On The Net: 35th Annual Grammy Awards – 1993". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Rock On The Net: 36th Annual Grammy Awards – 1994". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Rock On The Net: 39th Annual Grammy Awards – 1997". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "40th Annual Grammy Award Nominations Coverage (1998) |DigitalHit.com". Digitalhit.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Complete List Of 2004 Grammy Nominations". Music-slam.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Complete List Of 2005 Grammy Nominees". Music-slam.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Winners Database". billboardmusicawards.com. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ a b "Rock On The Net: 1991 MTV Video Music Awards". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Rock On The Net: 1996 MTV Video Music Awards". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Kangas, Chaz (September 6, 2012). "The 1997 Edition Was the Best MTV Video Music Awards". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b SNOW, SHAUNA (February 22, 1996). "5 Films Head Nominations for NAACP Image Awards". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "2001 NAACP Image Awards". Infoplease.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Blackflix.com: 34th NAACP Image Award Nominees". Blackflix.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "2nd Annual STMA Winners". August 29, 2002. Archived from the original on August 29, 2002. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "2003 Soul Train Music Awards Nominees". Billboard. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Ashanti, Amerie Lead Pack Of Nominees For Soul Train Awards". MTV News. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "19th Annual Soul Train Awards Nominations". Billboard. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Chief LL Cool J", a story on page 55 of the issue of the magazine Jet that is cover dated Dec 26, 1988 - Jan 2, 1989.

- ^ Gregory, Andy (July 5, 2002). International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002. Europa Publication. p. 308. ISBN 978-1857431612. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Calendar". Billboard. No. February 1, 1997. February 1, 1997. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "LL Cool J | Long Island Music Hall of Fame". Limusichalloffame.org. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "BET Hip Hop Awards winners". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ LL Cool J extends his reach during Gray Line New York's "Ride Of Fame" induction ceremony, which honored the native New Yorker Monday at Manhattan's Pier 78., People.com, May 14, 2013.

- ^ "LL Cool J gets honorary degree from Northeastern". Northeastern.edu. 505. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (January 21, 2016). "LL Cool J Receives a Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". Variety. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Fela nominated for 2021 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". Premiumtimesng.com. February 12, 2021. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "LL COOL J Honored With Key To The City In Queens, New York During First Rock The Bells Festival". HipHopDX. August 8, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ "LL Cool J Honored With Key To Queens, New York". BET. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ "LL Cool J Received The Key To The City Of Queens During Inaugural Rock The Bells Festival". The Root. August 9, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ "february 2000 | blackfilm.com | features | naacp image awards nominees". Blackfilm.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Blockbuster Entertainment Award winners". Variety. May 9, 2000. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Filmmakers.com : Film : The 2004 Black Reel Awards Nominations Announced". Filmmakers.com. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ King, Susan (March 4, 2011). "'For Colored Girls' wins for best film at NAACP Image Awards". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Teen Choice Awards 2011 Nominees Announced: Harry Potter vs Twilight". The Huffington Post. June 29, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "NAACP Image Awards 2012: Full list of winners". ABC7 Los Angeles. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Teen Choice Awards 2012: Complete Winners List". MTV News. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Television Academy. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "The 44th NAACP Image Award complete winners list". Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Teen Choice 2013 – August 11 on FOX – Vote Every Day!". August 21, 2013. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "NAACP Image Awards 2014: Complete winners list". Los Angeles Times. February 22, 2014. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "EIC Announces Nominations For 18th Annual PRISM Awards- Nods for Julia Roberts, Meryl Streep, Oprah, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Edie Falco, Allison Janney, LL Cool J, Jewel". PRWeb. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Team, The Deadline (December 9, 2014). "'Selma' & 'Get On Up' Lead NAACP Image Awards Nominations". Deadline. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Television – 'Creed,' 'Empire' Top NAACP Image Award Nominations; Full List". The Hollywood Reporter. February 4, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners". Television Academy. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "List: Who won People's Choice Awards?". USA Today. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "People's Choice Awards 2017: Full List Of Nominees". People's Choice. November 15, 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- LL Cool J; Karen Hunter (1997). I Make My Own Rules. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3121-7110-0.

External links[edit]

- LL Cool J

- 1968 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American rappers

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American rappers

- 429 Records artists

- African-American Catholics

- African-American male actors

- African-American male rappers

- African-American record producers

- African-American songwriters

- American hip hop record producers

- American male film actors

- American male rappers

- American male songwriters

- American male television actors

- American philanthropists

- Def Jam Recordings artists

- Grammy Award winners for rap music

- Male actors from Queens, New York

- Rappers from Queens, New York

- People from Bay Shore, New York

- People from Hollis, Queens

- People from St. Albans, Queens

- Pop rappers

- Record producers from New York (state)

- Songwriters from New York (state)

- Kennedy Center honorees