LaVaughn Robinson

LaVaughn Robinson | |

|---|---|

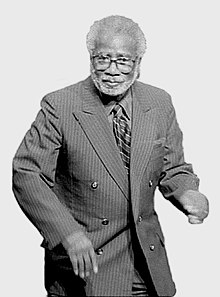

Robinson in 1998 | |

| Born | LaVaughn Evett February 9, 1927 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | January 22, 2008 (aged 80) Philadelphia |

| Occupation(s) | Tap Dancer, Choreographer, Teacher |

| Spouse | Edna Martin Robinson |

LaVaughn Robinson (born LaVaughn Evett) (February 9, 1927 – January 22, 2008)[1] was an American tap dancer, choreographer, and teacher.

A virtuoso tap dancer, Robinson perfected a high speed, low to the ground, a cappella style of dance that was characterized by elegance, precision, and clarity of sound. In a career spanning over 70 years, he started performing on the street, then in nightclubs, and finally in national and international tap festivals. He was recognized by the National Endowment of the Arts as a "Living National Treasure", received a NEA National Heritage Fellowship in 1989, a lifetime honor,[2] and a 1992 Pew Fellowship in the Arts.

Career

[edit]Street dancing

[edit]LaVaughn Robinson was born in South Philadelphia, one of seven brothers and seven sisters.[3] His mother (Catherine Griffin Robinson) taught him his first tap dancing step, the plain time step, at the age of seven. During the Depression, Philadelphia was a Mecca of tap dancing; the Nicholas Brothers (Fayard and Harold) and the Condos Brothers (Steve, Frank, and Nick) came from Robinson's neighborhood. Robinson learned from older street dancers, who vied for the best corners for busking. The elements of successful busking consisted of the ability to catch the attention of passersby, build a crowd, and then pass the hat. The competition required fierce demonstration of dancing prowess, like a gunfighter riding into town and challenging the local champion, with the winners getting better corners. The ultimate corner in Philadelphia was at Broad and South Streets. The better the dance ability, the nearer to Broad Street the dancer would be permitted busk. Broad Street being the same as 14th Street, the corners at either 2nd and South or 25th and South implied modest dance skills.[3] Although he had no formal dance training, this competitive zeal influenced Robinson's style, and Broad and South became his corner at the age of 13. He also danced and played in a tramp band (washboard, washtub bass, and kazoo), and when he was older, he busked in clubs. Robinson earned enough money by busking to buy his own clothes, contribute to paying for the family groceries, and to go to the Earle Theater.[4] It was here that Robinson saw the great tap dancers of the day: Baby Lawrence who performed with Count Basie Orchestra, the Nicholas Brothers with Dolly Dawn and the Dawn Patrol, and Robinson's particular favorite Teddy Hale with Louis Jordan. Robinson admired Teddy Hale's rendition of "Begin the Beguine", and particularly liked Hale's improvisational style, in which on successive performances, he performed entirely different dances, as opposed to a fixed act—the norm at the time. At this formative age, Robinson met Henry Meadows, an older dancer who took an interest in Robinson, and taught him a close to the ground, fast step called a paddle and roll, which was to be an important element in Robinson's mature style. Henry Meadows partnered with Robinson, on and off, over a period of 40 years.[5]

Club dancing

[edit]After Robinson graduated from Benjamin Franklin High School in Philadelphia, he served in the Army from 1945 to 1947.[6] Separating from the Army, he began his career in Philadelphia with booking agents Eddie Suez and Bernie Rothbard of the Suez/Rothbard Agency. As Henry Meadows preferred staying in Philadelphia, Robinson partnered with Howard Blow, a fast tempo tap dancer, and learned from Bobby Jones, another high speed dancer also from Philadelphia. "Howard and LaVaughn" performed in clubs owned by Frank Palumbo and opened for Cab Calloway, for Tommy Dorsey's Band, and on the same stage at the Apollo Theater with Ella Fitzgerald. Robinson also danced with Eddie Sledge and Tony Lopez when he worked for Eddie Smith, a booking agent who handled only trios and quartets. Robinson performed in a close rhythms style, avoiding splits, jumps, and flips of the style of the Nicholas Brothers, after suffering injuries to his legs.[5] He performed at the Broadwood Hotel and Palumbo's, then the resort hotels in the Catskills, Club Delisa in Chicago,[5] the 500 Club and the Harlem Club both in Atlantic City, New Jersey and throughout Canada. As tastes in music changed and the era of Swing came to an end, Robinson had the opportunity to work with John Coltrane and Charlie Parker. At the time, Robinson worked from music charts. John Coltrane said: "Oh, I can play that." But he did not play it as it was on the page. The improvisational style proved incompatible with Robinson's dancing. Robinson said to Coltrane: "Well, look, I don't need the music, because I'm dancing the way I like to dance and the way I wanted to dance."[5] Robinson focused his repertoire on tap as music, "sound tap," that made accompaniment a redundant distraction.

Professor of tap dancing

[edit]Robinson lived in Boston from 1965 to 1973, then returned to Philadelphia. Robinson started rehearsing at nights in the basement of the Neff Building in Philadelphia with Jerry Tapps, whose daytime job was the building's elevator operator. They developed a routine—Telephone, which was a series of calls and responses exchanged between two dancers. It was Tapps who encouraged Robinson to dance solo and to teach. Tapps inspired Robinson to create his signature solo dance, Artistry in Taps (also known as For Drummers Only).[5] In 1980, he joined the faculty of the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.[2] Teaching a generation of tap dancers, he taught a series of études that he developed over the course of his career, and he included elements of Telephone in his classes. In this time period, he also danced in a trio with Sandra Janoff, a teacher, and Germaine Ingram, an attorney. Later, he danced in a duo with Ingram. He was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment of the Arts in 1989 [2] and a Pew Fellowship in the Arts for Choreography and Performance Arts in 1992.[7] Robinson performed Artistry in Taps at the awards concert in the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In 2000, he won the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, Governor's Arts Award for Artist of the Year.[8] The University of the Arts named him Distinguished Professor in 2005, a title he held until his death.[9] Much in demand, he was a frequent featured performer throughout the U.S., and danced in Africa, Europe, and Russia.

Personal life

[edit]Robinson and his wife Edna (Martin) were married for 55 years, and they have three sons, LaVaughn Jr., Gregory, and Shelton. He died in Philadelphia of heart failure.[6]

Contribution to dance and technique

[edit]Had Robinson attended dance school in the 1930s, he would have learned a slower Broadway style of tap dancing. Coming from a street tradition that emphasized speed and flash, his mature style developed from close observation and imitation of the dancers of his day with particular interest in fast dancing. Robinson's encyclopedic knowledge of tap dancers, and his sense of the importance of the history, led him to create dances such as Robinson's Waltz Clog in tribute to Pat Rooney and Robinson's Impersonation of Bill Bailey impersonating Bill "Bojangles" Robinson imitating Peg Leg Bates. In the piece, he opens with a basic "Bojangles" time step before jumping into a one-legged Peg Leg Bates step. Known as the fastest taps in the business,[10] Robinson was a master and innovator of the paddle and roll step. The exact origins of the paddle and roll is not certain. Not seen in tap dancing of the 1920s, elements of it appeared in the 1930s in the dancing of John Bubbles and Willie Bryant; one story tells of it being brought to New York in 1937 by Walter Green.[11] The paddle and roll solidly entered the vocabulary of tap dancing in the late 1940s. Paddle and roll is a combination of heel and toe taps sounded as sixteenth notes creating a drum roll sound. From that one basic step, Robinson was able to create an endless number of variations. Fundamentally constructing compositions on the paddle, Robinson was able to subdivide the quarter note, macro beat into four sixteenth note beats. This also allowed him to easily subdivide the beat further. Most other tap compositions originate from swing eighth note beats, commonly through the flap or shuffle. This fundamental only easily allows tap composers to subdivide the quarter note, macro beat, into triplet eighth note beats. Employing his innovative subdivision scheme, even when Robinson used patterns common to many tap dancers, the steps fit into these complicated structures on the microscopic scale. So combinations that would be slow, broad gestures in other works become quick, fleeting details in his highly complex, intricate, infectious compositions. "Robinson elevated the art form of tap. The rhythmic intricacy and complexity that he invented developed tap into a mature percussive musical form. So much of what tap dancers do today would not be possible without LaVaughn's innovations."[12] In an encapsulation of a lifetime of thinking about tap dance, his solo piece Artistry in Taps, contains a wealth of the ideas that can be expressed in tap dancing. A completely choreographed piece developed over decades, Robinson drew on all the aspects of his life experience.

References

[edit]- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (February 6, 2008). "LaVaughn Robinson, Tap Virtuoso and Teacher, Dies at 80". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Lifetime Honors, National Heritage Award, LaVaughn E. Robinson". National Endowment of the Arts. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ a b Frank, Rusty E. (1994). Tap! The greatest Tap Dance Stars and Their Stories, 1900 - 1955 Revised Edition. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80635-5.

- ^ Earle Theater http://cinematreasures.org/theater/1806/

- ^ a b c d e "Artistry in Tap" http://www.danceadvance.org/03archives/lrobinson/index.html Archived 2003-09-14 at archive.today

- ^ a b Sims, Gayle Ronan (January 27, 2008). "World-renowned tap dancer, named a 'national treasure'". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- ^ Pew Fellows 1992 http://www.pewarts.org/92/Robinson/index.html

- ^ Pa Governor's Award "PCA - Governor's Awards for the Arts". Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ Philadelphia Folklore Project "Philadelphia Folklore Project". Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ Tap Dance in America (1989) (TV)

- ^ Stearns, Marshall and Jean (1994). Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80553-7.

- ^ timothytapdancing - LaVaughn Robinson[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to LaVaughn Robinson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to LaVaughn Robinson at Wikimedia Commons