List of British colours lost in battle

This is a list of British colours lost in battle. Since reforms in 1747 each infantry regiment carried two colours, or flags, to identify it on the battlefield: a king's colour of the union flag and a regimental colour of the same colour as the regiment's facings. The colours were regarded as talismans of the regiment and it was considered a stain on the unit's honour if they were captured. To prevent this, the colours were protected in the field by a colour party of young officers and experienced sergeants, around which the regiment would rally. As the 19th century progressed, regiments found their colour parties became increasingly vulnerable and some chose not to carry them in the field. The loss of two colours at the 1879 Battle of Isandlwana led to parliamentary debates on whether they should still be carried in the field. Heavy casualties among the colour party of the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot at the 1881 Battle of Laing's Nek led to a ban on them being carried in battle and since 1882 none have been taken on active service.

Background

[edit]

The colours, flags, of a British Army infantry regiment serve to identify the unit and mark a rallying point for its troops. They were particularly important in early warfare when smoke on the battlefield could make it hard to discern friend from foe. The colours developed into important talismans for the regiments, representing its traditions and honour; to capture an enemy colour was considered a great achievement while allowing one's own colours to be captured, or "lost" to the enemy was considered a stain on the regiment's honour.[1][2] In combat the colours were carried by ensigns, the most junior and often youngest of the regiment's officers and were placed in the front and centre of the unit. Because of their value and conspicuity the ensigns faced considerable risk.[3][4] To assist the ensigns (who were often just 16 years old) in handling the heavy flags and to protect the colours a number of experienced sergeants, armed with spontoons, were assigned to the colour party.[5] From 1813 a new rank, colour sergeant, was introduced for these men as a mark of honour.[3] If the colour party took casualties other officers, sergeants and, if necessary, other ranks would take their place.[3][6] At the 1815 Battle of Waterloo 14 sergeants of the 40th (the 2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot were killed or wounded while serving in the colour party and at the 1854 Battle of the Alma the colour party of the 21st (Royal North British Fusilier) Regiment of Foot lost 3 officers and 17 sergeants.[6]

Colours were first regulated by order of George II in 1747. The recent Jacobite rising of 1745 had prompted the king to set in place army reforms to standardise uniforms, drill and tactics. He was keen to ensure the soldiers' loyalty to the crown rather than the colonel of their regiment (regiments up to this time were known by their colonel's name rather than an ordinal number).[7] The colours of line infantry regiments had previously varied in number and design according to the whims of their colonel; many bore the personal arms of their commander, rather than any national or royal insignia.[8] George's reforms standardised the colours to two per regiment: a "king's colour" (known as a "royal" or "queen's colour" during the reign of a queen), based on the union flag and a "second colour" (later known as the "regimental colour") with a field in the colour of the regiment's facings defaced by the new regimental numbers.[8] It was common for infantry colours to be consecrated by an Anglican priest, and by 1825 it became the norm that colours would be consecrated when being formally presented to the regiment, though there were exceptions.[9]

Preventing capture

[edit]

Regiments usually took great care to avoid their colours from falling into the hands of the enemy. During the surrender at Saratoga the colours of the 9th Regiment of Foot were smuggled back to England by their colonel, which was viewed by the Americans as a violation of the terms of the surrender.[10] The colours of the 94th Regiment of Foot were saved during the surrender following the 1880 Battle of Bronkhorstspruit by being hidden beneath the bed of a wounded soldier's wife, in an ambulance allowed to return to British lines.[11] On other occasions the colours have been deliberately destroyed to prevent their capture. The colours of the 51st (2nd Yorkshire West Riding) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) were burnt by their colonel at the 1811 Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro when he feared they were at risk of capture and on several occasions regiments threatened with capture while being transported at sea have weighted their colours and thrown them overboard.[12][13] On some occasions regiments have been offered the right to keep their colours during surrender negotiations, such was the case with the colours of the 4th, 23rd, 24th and 34th regiments of foot who retained their colours after the 1782 surrender of Minorca.[10] Despite the value placed on them colours were sometimes lost off the battlefield, the 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot (MacLeod's Highlanders) left them at their depot in Britain during the Peninsular War but could not find them upon their return; a light infantry regiment lost one colour in the post during the 19th century.[14]

The colours of units fighting in open order as light infantry were particularly vulnerable to attack and, as early as 1808, many such units did not carry their colours in the field.[14] In battle the colours were sometimes sent to the rear if they were considered to be at risk or attracting too much enemy fire.[12] Sometimes commanders considered the carrying of colours to be a hindrance to their units and ordered them left behind, as did General James Abercrombie during the 1758 Ticonderoga campaign.[15] By the 1860s many infantry regiments posted on active service chose to leave their colours safely behind at their depots.[16]

After the loss of the colours of the 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot at the 1879 Battle of Isandlwana there were debates in parliament as to whether colours should continue to be carried in the field. These were renewed after the heavy casualties suffered by the colour party of the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot at the 28 January 1881 Battle of Laing's Nek; British General Garnet Wolseley remarked that after this engagement any colonel that ordered the colours to be carried into action should be tried for the murders of the men lost carrying them.[11] The action led to the Secretary of State for War Hugh Childers issuing instructions on 29 July that colours were no longer to be taken into the field.[17] This was reinforced by a 2 March 1882 order from the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, the Duke of Cambridge, that regiments posted on active service leave their colours behind.[16] The colours of the 58th at Laing's Nek became the last to be carried into battle and those of the 1st battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment the last to be taken on active service when they were at Alexandria in 1882.[17]

Units without colours

[edit]Only the flags of British infantry regiments are known as colours, the flags of British cavalry regiments are called standards; these were not consecrated, and do not seem to have attracted the same level of veneration as their infantry counterparts.[18] From the early 19th century it became increasingly rare for cavalry standards to be taken into battle; very few were carried during the Peninsular War, for example. The light dragoons (a class of light cavalry that also included hussars and lancers) ceased to carry any standards after 1834, as by this time they fought most often as skirmishers in open order and hence would not be able to protect their standard.[19]

Infantry regiments lost their colours when designated as rifle units, which were intended to fight in skirmish order; this includes the 95th (Rifle) Regiment of Foot, the 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot and their modern-day successor The Rifles.[20] The Marines (from 1802 the Royal Marines), were organised into companies with only their administrative divisions receiving colours, which were not carried in the field.[21] The Royal Artillery did not carry colours, with their guns being considered the equivalent.[22]

List

[edit]This is a list of colours lost on the battlefield, or surrendered immediately afterwards, by infantry regiments of the British army since the 1747 reforms. Colours temporarily lost and recovered in the course of the battle are not listed. The list does not include units of the East India Company armies (and later the British Indian Army), colonial troops or militia.

| Image | Date | Unit | Colour | Battle | War | Captured by | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 August 1756 | 50th Regiment of Foot (American Provincials) | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Fort Oswego | Seven Years' War | France | These two units were ranked as regular regiments of foot but consisted of raw recruits from the colonies. They were disbanded shortly after the surrender at Fort Oswego. Two of these colours were recovered by British forces during the September 1760 capture of Montreal. | [23] | |

| 51st Regiment of Foot (Cape Breton Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | [23] | ||||||

| 15 October 1760 | Unknown regiment | Unknown colour | Battle of Kloster Kampen | Seven Years' War | France | [24] | ||

| 20 October 1775 | 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers) | Regimental colour | Surrender of Fort Chamblé | American War of Independence | Thirteen Colonies | Only one company of the regiment was present at this action | [25][26][23] | |

Surrender of colours at Saratoga Surrender of colours at Saratoga

|

17 October 1777 | 37th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Surrender at Saratoga | American War of Independence | United States of America | Other regiments, including the 9th and 62nd Regiments of Foot, successfully concealed their colours and returned them to Britain. Other colours were sent in the personal baggage of General John Burgoyne. | [27][28][29][30] |

| 1777-8 | 81st Regiment of Foot (Aberdeenshire Highland Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | At sea between Britain and Ireland | American War of Independence | United States of America | Captured by a privateer, possibly John Paul Jones | [27] | |

| 16 July 1779 | 17th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Stony Point | American War of Independence | United States of America | [31] | ||

| 21 September 1779 | 16th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Baton Rouge | American War of Independence | Spain | [27] | ||

The King's colour of the 7th Regiment is now exhibited at the West Point Museum |

17 January 1781 | 7th Regiment of Foot | King's colour | Battle of Cowpens | American War of Independence | United States of America | [25] | |

| 8 September 1781 | 64th Regiment of Foot | King's colour (possible) | Battle of Eutaw Springs | American War of Independence | United States of America | The 64th Regiment returned from America without its King's colour, it was possibly lost when it was driven back at the Battle of Eutaw Springs | [32] | |

A depiction of British colours (left) during the surrender at Yorktown |

19 October 1781 | 43rd Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour (possible) | Surrender at Yorktown | American War of Independence | United States of America, France |

The 43rd Regiment later claimed its colours weren't lost and had been left at the depot in New York. The 23rd Foot (Royal Welsh Fuzileers) and 33rd Regiment of Foot also surrendered at Yorktown but are believed to have hidden their colours beforehand. In addition to the British regiments 18 colours were captured from Hessian, Ansbach and Bayreuth units. | [25][33] |

| 19 October 1781 | 76th Regiment of Foot (MacDonald's Highlanders) | King's colour and regimental colour | ||||||

| 19 October 1781 | 80th Regiment of Foot (Royal Edinburgh Volunteers) | King's colour and regimental colour | ||||||

| 26/27 November 1781 | 15th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | French capture of Sint Eustatius | Anglo-French War (1778–1783) | France | [34] | ||

| 13th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] | ||||||

| 3 May 1783 | 98th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Siege of Bednore | Second Anglo-Mysore War | Mysore | [34] | ||

| 100th Regiment of Foot (Loyal Lincolnshire Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] | ||||||

| 102nd Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] | ||||||

| 1794 | 43rd (Monmouthshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Invasion of Guadeloupe | War of the First Coalition | France | [35] | ||

| 65th (2nd Yorkshire, North Riding) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [35] | ||||||

King's colour (left) and regimental colour (right) |

11 August 1806 | 2nd battalion, 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot (MacLeod's Highlanders) | King's colour and regimental colour | First British occupation of Buenos Aires | Anglo-Spanish War (1796–1808) | Spain | [36][35] | |

The Buffs defend their colours at Albuera |

16 May 1811 | 1st battalion, 3rd Regiment of Foot, "The Buffs" | Part of the regimental colour (staff, cords and part of flag lost, later recovered in counterattack) | Battle of Albuera | Peninsular War | France | The regimental colour was lost to a French attack but most of the flag was recovered in a counterattack by the 7th Regiment of Foot | [36][37] |

| 2nd battalion, 48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [36] | ||||||

| 2nd battalion, 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour | [36] | ||||||

| 22 July 1812 | 2nd battalion, 53rd (Shropshire) Regiment of Foot | Part of the King's colour (staff and some of the flag lost) | Battle of Salamanca | Peninsular War | France | [36] | ||

Two of the colours during the Siege of Bergen op Zoom |

8 March 1814 | 2nd battalion, 1st Regiment of Foot Guards | Unknown | Siege of Bergen op Zoom | War of the Sixth Coalition | France | Source just states "colours" lost. The Foot Guards of this period carried three king's colours: the colonel's, lieutenant-colonel's and major's colours. Unlike the king's colours of line regiments these had plain crimson fields. Each company also had a colour which was the union flag defaced with a badge, the 1st Foot Guards had 24 of these, one of which was carried in rotation as the regimental colour. | [36][38] |

| 4th battalion, 1st (Royal) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | The colours were weighted and thrown into the River Zoom by the regiment's adjutant in an attempt to save them from capture but were afterwards recovered by the French. | [36][39] | |||||

| 2nd battalion, 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot | Regimental colour | [36] | ||||||

| 16 June 1815 | 2nd battalion, 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour | Battle of Quatre Bras | Hundred Days | France | The colour came into the possession of General François-Xavier Donzelot who commanded the 2nd Infantry Division during the battle. It was inherited by his grandson who gave them away in payment for a debt. In 1909 the colour was sold to a British captain on holiday and returned to the regimental museum. The colour is now in the collection of the Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh. | [36][40] | |

King's colour carried by battalions of the King's German Legion |

18 June 1815 | 5th Kings German Legion Line Battalion | King's colour | Battle of Waterloo | War of the Sixth Coalition | France | [36] | |

| 8th Kings German Legion Line Battalion | King's colour | [36] | ||||||

The last stand of the 44th, the regimental colour is shown wrapped around Souter's waist |

13 January 1842 | 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Last stand at Jugdulluk | First Anglo-Afghan War | Afghanistan | Knowing they would be overrun by the Afghan forces Captain Souter and Lieutenant Cumberland took the colours from their staffs and tried to wrap them around their bodies. Cumberland was unable to button his coat over the queen's colour and handed it to Colour-Sergeant Carey who hid it under his sheepskin coat. Carey was killed and the colour lost, but Souter was captured by the Afghans who thought him worthy of ransom after mistaking the bright yellow colour for expensive clothing. Souter brought the regimental colour back with him when he was released some months later. | [41][42][43] |

The 24th advance at Chillianwala |

13 January 1849 | 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour | Battle of Chillianwala | Second Anglo-Sikh War | Sikh Empire | The colour was separated from its staff and carried by the wounded Private Battlestone during the retreat. Having refused to give up the colours to his comrades Battlestone fell dead, unnoticed. The colour was not found by the British the following morning; as it was not paraded by the Sikhs as a trophy it was perhaps taken by local villagers or camp followers. The battle was among the worst on record for losses of British colours, with nine from the British Indian units also lost. | [44][45][46] |

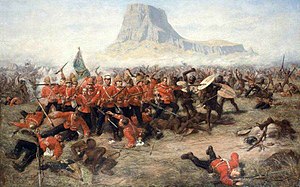

A depiction of a last stand around the regimental colour of the 2nd battalion, though there is no evidence that the colours were unfurled during the battle. |

22 January 1879 | 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Isandlwana | Anglo-Zulu War | Zulu Kingdom | Both colours of the 2nd battalion were lost on the battlefield, though part of one pole and a crown finial were recovered separately later.The queen's colour of the 1st battalion was also present at the battle; it was brought away by Lieutenants Melville and Coghill who were killed in their attempted flight. The colour was found in the Buffalo River by British forces on 4 February, near to where they died. | [47] |

| 27 July 1880 | 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Maiwand | Second Anglo-Afghan War | Afghanistan | This was the last loss of British colours. | [48] |

References

[edit]- ^ Mockler-Ferryman, A. F. (15 August 2020). The Life of a Regimental Officer. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 94. ISBN 978-3-7524-4345-5.

- ^ Knight, Ian (16 October 2008). Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Pen and Sword. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4738-1331-1.

- ^ a b c Jobson, Christopher (August 2009). Looking Forward Looking Back: Customs and Traditions of the Australian Army. Simon and Schuster. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-921941-64-1.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 168. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Fletcher, Ian (20 August 2012). Wellington's Foot Guards. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-78200-210-9.

- ^ a b Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84176-200-5.

- ^ a b Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ a b Holden, Major R. (1 January 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (203): 39. doi:10.1080/03071849509417946. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ a b Knight, Ian (16 October 2008). Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Pen and Sword. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-84415-801-0.

- ^ a b Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 January 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (203): 35–37. doi:10.1080/03071849509417946. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ a b Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 171. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ a b Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 170. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ a b Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 January 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (203): 31. doi:10.1080/03071849509417946. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-84176-200-5.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Infantry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84176-201-2.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-84176-200-5.

- ^ Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747-1881 (1): Cavalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-84176-200-5.

- ^ a b c Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 159. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Fortescue, J. W. (27 July 2020). A History of the British Army: Volume 2. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 367. ISBN 978-3-7523-5339-6. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Geddes, James D. (1975). "1638. British Colours in the American War of Independence". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 53 (214): 123–124. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44223096.

- ^ Kelleher, JP. "The 7th Royal Fusiliers and their part in The American War of Independence 1775 - 1781 and New Orleans 1815". Fusilier Museum London. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 160. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Troiani, Don; Schnitzer, Eric H. (August 2019). Don Troiani's Campaign to Saratoga - 1777: The Turning Point of the Revolutionary War in Paintings, Artifacts, and Historical Narrative. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-8117-6853-5.

- ^ Messenger, Charles (13 September 1993). For Love of Regiment: A History of British Infantry, Volume One, 1660–1914. Pen and Sword. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-4738-1438-7.

- ^ Furneaux, Rupert (1971). Saratoga: the Decisive Battle. Allen & Unwin. p. 282. ISBN 9780049730052.

- ^ Webb, Edward Arthur Howard (1911). A History of the Services of the 17th (the Leicestershire) Regiment: Containing an Account of the Formation of the Regiment in 1688, and of Its Subsequent Services, Revised and Continued to 1910. Vacher. p. 256.

- ^ Cook, H. C. B.; Jones, Maurice E. (1976). "1658. British Colours in the American War of Independence". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 54 (217): 55. ISSN 0037-9700.

- ^ Geddes, James D. (1975). "1638. British Colours in the American War of Independence". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 53 (214): 124. ISSN 0037-9700. JSTOR 44223096.

- ^ a b c d e Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 161. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ a b c Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 162. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Burnham, Robert; McGuigan, Ron (9 August 2010). The British Army Against Napoleon: Facts, Lists and Trivia, 1805-1815. Pen and Sword. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-78383-339-9.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 163. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Fletcher, Ian (20 August 2012). Wellington's Foot Guards. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1-78200-210-9.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 January 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (203): 35. doi:10.1080/03071849509417946. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ "The King's Colour of the 69th Regiment". Peoples Collection Wales. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Carter, Thomas (1864). Historical Record of the Forty-fourth, or the East Essex Regiment of Foot. Compiled by Thomas Carter ... With illustrations. London: W. O. Mitchell. p. 9.

- ^ Kekewich, Margaret (13 June 2011). Retreat and Retribution in Afghanistan 1842: Two Journals of the First Afghan War. Casemate Publishers. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-84468-590-5.

- ^ Bray, Edward William (1865). Journal of Affghan War in 1842. Nelson and Company. p. 72.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 165. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 166. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.

- ^ Thackwell, Joseph (1851). Narrative of the second Sikh war in 1848-49. With a detailed account of the battles of Ramnugger, the passage of the Chenab, Chillianwallah, Goojerat, &c. ... Second edition, revised with additions. London: Richard Bentley. p. 162.

- ^ Knight, Ian (16 October 2008). Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Pen and Sword. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-84415-801-0.

- ^ Holden, Major R. (1 February 1895). "The Vicissitudes of Regimental Colours". Royal United Services Institution. Journal. 39 (204): 166–167. doi:10.1080/03071849509417953. ISSN 0035-9289.