1983 Beirut barracks bombings

| 1983 Beirut barracks bombings | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Iran–Iraq War and the Lebanese Civil War | |

A smoke cloud rises from the rubble of the bombed barracks at Beirut International Airport (BIA). | |

| Location |

|

| Date | October 23, 1983 06:22 am |

Attack type | Suicide attack, truck bombs |

| Deaths | Total: 307

|

| Injured | 150 |

| Perpetrator |

|

| Motive | United States and French support for Iraq |

On October 23, 1983, two truck bombs were detonated at buildings in Beirut, Lebanon, housing American and French service members of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF), a military peacekeeping operation during the Lebanese Civil War. The attack killed 307 people: 241 U.S. and 58 French military personnel, six civilians, and two attackers.

Early that Sunday morning, the first suicide bomber detonated a truck bomb at the building serving as a barracks for the 1st Battalion 8th Marines (Battalion Landing Team – BLT 1/8) of the 2nd Marine Division, killing 220 marines, 18 sailors and three soldiers, making this incident the deadliest single-day death toll for the United States Marine Corps since the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II and the deadliest single-day death toll for the United States Armed Forces since the first day of the Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War.[1][2] Another 128 Americans were wounded in the blast. 13 later died of their injuries, and they are counted among the number who died.[3] An elderly Lebanese man, a custodian/vendor who was known to work and sleep in his concession stand next to the building, was also killed in the first blast.[4][1][5] The explosives used were later estimated to be equivalent to as much as 12,000 pounds (5,400 kg) of TNT.[6][7][8]

Minutes later, a second suicide bomber struck the nine-story Drakkar building, a few kilometers away, where the French contingent was stationed. 55 paratroopers from the 1st Parachute Chasseur Regiment and three paratroopers of the 9th Parachute Chasseur Regiment were killed and 15 injured. It was the single worst French military loss since the end of the Algerian War.[9] The wife and four children of a Lebanese janitor at the French building were also killed, and more than twenty other Lebanese civilians were injured.[10]

A group called Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for the bombings and said that the aim was to force the MNF out of Lebanon.[11] According to Caspar Weinberger, then United States Secretary of Defense, there is no knowledge of who did the bombing.[12] Some analysis highlights the role of Hezbollah and Iran, calling it "an Iranian operation from top to bottom".[13] There is no consensus on whether Hezbollah existed at the time of bombing.[14] The attacks eventually led to the withdrawal of the international peacekeeping force from Lebanon, where they had been stationed following the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) withdrawal in the aftermath of Israel's 1982 invasion of Lebanon.

Beirut: June 1982 to October 1983

[edit]Timeline

[edit]- 6 June 1982 – Israel undertakes military action in Southern Lebanon: Operation "Peace for Galilee."

- 23 August 1982 – Bachir Gemayel is elected to be Lebanon's president.

- 25 August 1982 – A MNF of approximately 400 French, 800 Italian soldiers and 800 marines of the 32nd Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU) are deployed in Beirut as part of a peacekeeping force to oversee the evacuation of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) guerrillas.

- 10 September 1982 – The PLO retreats from Beirut under MNF protection. Subsequently, the 32nd MAU is ordered out of Beirut by the President of the United States.

- 14 September 1982 – Lebanon's President, Bachir Gemayel, is assassinated.

- 16 September to 18 September 1982 – The Sabra and Shatila massacre occurs.

- 19 September 1982 – The destroyer USS John Rodgers and nuclear cruiser USS Virginia, operating off the coast of Beirut, conduct a naval bombardment onto the town of Suk al Gharb, in the hills overlooking Beirut, in support of the Lebanese Army, after it is nearly overrun by Syrian-backed Druze militiamen and Palestinian guerrillas. Over 300 rounds of 5" shells are fired to suppress the attack.[15]

- 20 September 1982 – The Beirut residence of the U.S. ambassador is shelled; for a second day US naval ships again conduct counter fire operations.[16]

- 21 September 1982 – Bachir Gemayel's brother, Amine Gemayel, is elected to be Lebanon's president.

- 29 September 1982 – The 32nd MAU is redeployed to Beirut (primarily at the BIA) rejoining 2,200 French and Italian MNF troops already in place.

- 30 October 1982 – The 32nd MAU is relieved by the 24th MAU.

- 15 February 1983 – The 32nd MAU, redesignated as the 22nd MAU, returns to Lebanon to relieve the 24th MAU.

- 18 April 1983 – The U.S. Embassy bombing in Beirut kills 63, of whom 17 are Americans.

- 17 May 1983 – The May 17 Agreement is signed.

- 30 May 1983 – The 24th MAU relieves the 22nd MAU.[17]

Mission

[edit]

On June 6, 1982, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) initiated Operation "Peace for Galilee" and invaded Lebanon in order to create a 40 km buffer zone between the PLO and Syrian forces in Lebanon and Israel.[18][19][20] The Israeli invasion was tacitly approved by the U.S., and the U.S. provided overt military support to Israel in the form of arms and materiel.[21] The U.S.' support for Israel's invasion of Lebanon taken in conjunction with U.S. support for Lebanese President Bachir Gemayel and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) alienated many.[22]

Bachir Gemayel was the legally elected president, but he was a partisan Maronite Christian and covert associate of Israel.[23] These factors served to disaffect the Lebanese Muslim and Druze communities. This animosity was made worse by the Phalangist, a right-wing, largely Maronite-Lebanese militia force closely associated with President Gemayel. The Phalangist militia was responsible for multiple, bloody attacks against the Muslim and Druze communities in Lebanon and for the 1982 atrocities committed in the PLO refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila by Lebanese Forces (LF), while the IDF provided security and looked on.[24][25]

The Phalangist militia's attacks on Sabra and Shatila were purportedly a response to the September 14, 1982, assassination of President-elect Bachir Gemayel.[24][26][27] Amine Gemayel, Bachir's brother, succeeded Bachir as the elected president of Lebanon, and Amine continued to represent and advance Maronite interests.

All of this, according to British foreign correspondent Robert Fisk, served to generate ill will against the MNF among Lebanese Muslims and especially among the Shiites living in the slums of West Beirut. Lebanese Muslims believed the MNF, and the Americans in particular, were unfairly siding with the Maronite Christians in their attempt to dominate Lebanon.[28][29][30] As a result, this led to artillery, mortar, and small arms fire being directed at MNF peacekeepers by Muslim factions. Operating under the peacetime rules of engagement, MNF peacekeepers – primarily U.S. and French forces – used minimum use of force as possible in order to avoid compromising their neutral status.[31] Until October 23, 1983, there were ten guidelines issued for each U.S. marine member of the MNF:

- When on post, mobile or foot patrol, keep loaded magazine in weapon, bolt closed, weapon on safe, no round in the chamber.

- Do not chamber a round unless instructed to do so by a commissioned officer unless you must act in immediate self-defense where deadly force is authorized.

- Keep ammo for crew-served weapons readily available but not loaded in the weapon. Weapons will be on safe at all times.

- Call local forces to assist in self-defense effort. Notify headquarters.

- Use only minimum degree of force to accomplish any mission.

- Stop the use of force when it is no longer needed to accomplish the mission.

- If you receive effective hostile fire, direct your fire at the source. If possible, use friendly snipers.

- Respect civilian property; do not attack it unless absolutely necessary to protect friendly forces.

- Protect innocent civilians from harm.

- Respect and protect recognized medical agencies such as Red Cross, Red Crescent, etc.

The perimeter guards at the U.S. Marine headquarters on the morning of October 23, 1983, were in full compliance with rules 1–3 and were unable to shoot fast enough to disable or stop the bomber (see Bombings: Sunday, October 23, 1983 below).[32]

In 1982, the Islamic Republic of Iran established a base in the Syrian-controlled Beqaa Valley in Lebanon. From that base, Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) "founded, financed, trained and equipped Hezbollah to operate as a proxy army" for Iran.[33] Some analysts believe the newly formed Islamic Republic of Iran was heavily involved in the bomb attacks and that a major factor leading it to orchestrate the attacks on the barracks was America's support for Iraq in the Iran–Iraq War and its extending of $2.5 billion in trade credit to Iraq while halting the shipments of arms to Iran.[34]

A few weeks before the bombing, Iran warned that providing armaments to Iran's enemies would provoke retaliatory punishment.[Notes 1] On September 26, 1983, "the National Security Agency (NSA) intercepted an Iranian diplomatic communications message from the Iranian intelligence agency, the Ministry of Information and Security (MOIS)," to its ambassador, Ali Akbar Mohtashemi, in Damascus. The message directed the ambassador to "take spectacular action against the American Marines."[35] The intercepted message, dated September 26, would not be passed to the Marines until October 26: three days after the bombing.[36]

Much of what is now public knowledge of Iranian involvement, e.g., PETN purportedly supplied by Iran, the suicide bomber's name and nationality, etc., in the bombings was not revealed to the public until the 2003 trial, Peterson, et al v. Islamic Republic, et al.[6] Testimony by Admiral James "Ace" Lyon's, U.S.N. (Ret), and FBI forensic explosive investigator Danny A. Defenbaugh, plus a deposition by a Hezbollah operative named Mahmoud (a pseudonym) were particularly revealing.[37]

Incidents

[edit]On July 14, 1983, a Lebanese Armed Forces patrol was ambushed by Lebanese Druze militia elements and from July 15–17, Lebanese troops engaged the Shia Amal militia in Beirut over a dispute involving the eviction of Shiite squatters from a schoolhouse. At the same time, fighting in the Shuf between the LAF and Druze militia escalated sharply. On July 22, Beirut International Airport (BIA), the headquarters of the U.S. 24th Marine Amphibious Unit (24th MAU), was shelled with Druze mortar and artillery fire, wounding three U.S. marines and causing the temporary closure of the airport.[31]

On July 23, Walid Jumblatt, leader of the predominantly Druze Progressive Socialist Party (PSP), announced the formation of a Syrian-backed "National Salvation Front" opposed to the May 17 Agreement. In anticipation of an IDF withdrawal from the Alayh and Shuf districts, fighting between the Druze and LF and between the Druze and LAF, intensified during the month of August. Druze artillery closed the BIA between 10 and 16 August, and the Druze made explicit their opposition to LAF deployment in the Shuf. The LAF also clashed with the Amal militia in Beirut's western and southern suburbs.[31]

As the security situation deteriorated, US positions at BIA were subjected to increased fire. On August 10 and 11, an estimated thirty-five rounds of mortar and rocket fire landed on US positions, wounding one marine. On August 28, in response to constant mortar and rocket fire upon US positions, US peacekeepers returned fire for the first time. On the following day, US artillery silenced a Druze battery after two marines were killed in a mortar attack. On August 31, the LAF swept through the Shia neighborhood of West Beirut, establishing temporary control over the area.[31]

On September 4, the IDF withdrew from the Alayh and Shuf Districts, falling back to the Awwali River. The LAF was not prepared to fill the void, moving instead to occupy the key junction at Khaldah, south of BIA. That same day, BIA was again shelled, killing two marines and wounding two others. No retaliation was given due to the ROE. As the LAF moved slowly eastward into the foothills of the Shuf, accounts of massacres, conducted by Christians and Druze alike, began to be reported.[31]

On September 5, a Druze force, reportedly reinforced by PLO elements, routed the Christian LF militia at Bhamdun and all but eliminated the LF as a military factor in the Alayh District. This defeat obliged the LAF to occupy Souk El Gharb to avoid conceding all of the high ground overlooking BIA to the Druze. U.S. positions were again subjected to constant indirect fire attacks; consequently, counterbattery fire based on target acquisition radar data was employed. F-14 tactical airborne reconnaissance (TARPS) missions were conducted for the first time on September 7. On September 8, naval gunfire from offshore destroyers was employed for the first time in defense of the U.S. Marines.[31]

On September 25, a ceasefire was instituted that same day and Beirut International Airport reopened five days later. On October 1, Walid Jumblatt announced a separate governmental administration for the Shuf and called for the mass defection of all Druze elements from the LAF. Nevertheless, on 14 October the leaders of Lebanon's key factions agreed to conduct reconciliation talks in Geneva, Switzerland. Although the ceasefire officially held into mid-October, factional clashes intensified and sniper attacks on MNF contingents became commonplace. On October 19, four marines were wounded when a US convoy was attacked by a remotely detonated car bomb parked along the convoy route.[31]

On October 16, thousands of Shia pilgrims were holding a procession celebrating Ashura in Nabatieh when an Israeli military convoy attempted to pass along the same road as the pilgrims. The Israelis, apparently unaware of the holiday or its significance, attempted to clear the road resulting in a confrontation which ended in an overturned jeep set alight, along with two transport trucks and stone pelting. The Israelis opened fire and tossed grenades resulting in at least two dead and fifteen wounded.[38] This incident significantly increased tensions between the Shia community in Lebanon and Israel. This by extension, worsened increased tensions with the US.

Bombings: Sunday, October 23, 1983

[edit]

At around 06:22, a 19-ton yellow Mercedes-Benz stake-bed truck drove to the Beirut International Airport. The 1st Battalion 8th Marines (BLT), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Larry Gerlach, was a subordinate element of the 24th MAU. The truck was not the water truck they had been expecting. Instead, it was a hijacked truck carrying explosives. The driver turned his truck onto an access road leading to the compound. He drove into and circled the parking lot, and then he accelerated to crash through a 5 feet (1.5 m)-high barrier of concertina wire separating the parking lot from the building. The wire popped "like somebody walking on twigs."[39]

The truck then passed between two sentry posts and through an open vehicle gate in the perimeter chain-link fence, crashed through a guard shack in front of the building and smashed into the lobby of the building serving as the barracks for the 1st Battalion 8th Marines (BLT). The sentries at the gate were operating under rules of engagement which made it very difficult to respond quickly to the truck. On the day of the bombing, the sentries were ordered to keep a loaded magazine inserted in their weapon, bolt closed, weapon on safe and no round in the chamber. Only one sentry, LCpl Eddie DiFranco, was able to chamber a round. However, by that time the truck was already crashing into the building's entryway.[40]

The suicide bomber, an Iranian national named Ismail Ascari,[41][42] detonated his explosives, which were later estimated to be equivalent to approximately 12,000 pounds of TNT.[6][7][8] The force of the explosion collapsed the four-story building into rubble, crushing to death 241 American servicemen. According to Eric Hammel in his history of the U.S. Marine landing force,

The force of the explosion initially lifted the entire four-story structure, shearing the bases of the concrete support columns, each measuring fifteen feet in circumference and reinforced by numerous one-and-three-quarter-inch steel rods. The airborne building then fell in upon itself. A massive shock wave and ball of flaming gas was hurled in all directions.[43]

The explosive mechanism was a gas-enhanced device consisting of compressed butane in canisters employed with pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN) to create a fuel-air explosive.[6][7] The bomb was carried on a layer of concrete covered with a slab of marble to direct the blast upward.[44] Despite the lack of sophistication and wide availability of its component parts, a gas-enhanced device can be a lethal weapon. These devices were similar to fuel-air or thermobaric weapons, explaining the large blast and damage.[45] An after-action forensic investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) determined that the bomb was so powerful that it probably would have brought down the building even if the sentries had managed to stop the truck between the gate and the building.[37]

Less than ten minutes later, a similar attack occurred against the barracks of the French 3rd Company of the 1st Parachute Chasseur Regiment, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) away in the Ramlet al Baida area of West Beirut.[46] As the suicide bomber drove his pickup truck toward the "Drakkar" building, French paratroopers began shooting at the truck and its driver.[46] It is believed that the driver was killed and the truck was immobilized and rolled to stop about 15 yards (14 m) from the building.[46]

A few moments passed before the truck exploded, bringing down the nine-story building and killing 58 French paratroopers.[46] It is believed that this bomb was detonated by remote control and that, though similarly constructed, it was smaller than and slightly less than half as powerful as the one used against the Marines.[46] Many of the paratroopers had gathered on their balconies moments earlier to see what was happening at the airport.[47] It was France's worst military loss since the end of the Algerian War in 1962.[48]

Rescue and recovery operations: October 23 to 28, 1983

[edit]American

[edit]

Organized rescue efforts began immediately – within three minutes of the bombing – and continued for days.[49] Unit maintenance personnel were not billeted in the BLT building, and they rounded up pry bars, torches, jacks and other equipment from unit vehicles and maintenance shops and began rescue operations.[50] Meanwhile, combat engineers and truck drivers began using their organic assets, i.e., trucks and engineering equipment, to help with the rescue operations.[51]

24th MAU medical personnel, Navy dentists LT Gil Bigelow and LT Jim Ware, established two aid stations to triage and treat casualties.[52][53][54] Medevac helicopters, CH-46s from Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron (HMM-162), were airborne by 6:45 AM.[55] U.S. Navy medical personnel from nearby vessels of the U.S. Sixth Fleet went ashore to assist with treatment and medical evacuation of the injured,[56][57] as did sailors and shipboard marines who volunteered to assist with the rescue effort.[58] Lebanese, Italian, British, and even French troops, who had suffered their own loss, provided assistance.[59][60]

Many Lebanese civilians voluntarily joined the rescue effort.[61] Especially important was a Lebanese construction contractor, Rafiq Hariri of the firm Oger-Liban, who provided heavy construction equipment, e.g., a 40-ton P & H crane, etc., from nearby BIA worksites. Hariri's construction equipment proved vitally necessary in lifting and removing heavy slabs of concrete debris at the barracks site just as it had been necessary in assisting with clearing debris after the April U.S. Embassy attack.[61][62]

While the rescuers were at times hindered by hostile sniper and artillery fire, several marine survivors were pulled from the rubble at the BLT 1/8 bomb site and airlifted by helicopter to the USS Iwo Jima, located offshore. U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force and Royal Air Force medevac planes transported the seriously wounded to the hospital at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus and to U.S. and German hospitals in West Germany.[58][63] A few survivors, including Lt. Col. Gerlach, were sent to the Italian MNF dispensary and to Lebanese hospitals in Beirut.[64][65] Israel's offers to medevac the wounded to hospitals in Israel were rejected as politically unacceptable even though Israeli hospitals were known to provide excellent care and were considerably closer than hospitals in Germany.[17][66]

At about noon Sunday, October 23, the last survivor was pulled from the rubble; he was LTJG Danny G. Wheeler, Lutheran chaplain for BLT 1/8.[67] Other men survived beyond Sunday, but they succumbed to their injuries before they could be extracted from the rubble.[68] By Wednesday, the majority of the bodies and body parts had been recovered from the stricken barracks, and the recovery effort ended on Friday.[69][70] After five days, the FBI came in to investigate, and the Marines returned to normal duties.[70]

French

[edit]"The explosion at the French barracks blew the whole building off its foundations and threw it about 6 meters (20 feet) westward, while breaking the windows of almost every apartment house in the neighborhood .... Grim-faced French paratroopers and Lebanese civil-defense workers aided by bulldozers also worked under spotlights through the night at the French barracks, trying to pull apart the eight stories of 90 centimeter (3 foot) thick cement that had fallen on top of one another and to reach the men they could still hear screaming for help. They regularly pumped oxygen into the mountain of rubble to keep those who were still trapped below alive."[10]

Victims

[edit]The explosions resulted in 346 casualties, of which 234 (68%) were killed immediately, with head injuries, thoracic injuries and burns accounting for a large number of deaths.[71]

The New York Times printed a list of the identified casualties on October 26, 1983.[72] Another list of those who survived the incident was published by the Department of Defense. The information had to be re-printed, as individuals were misidentified, and family members were told incorrect statuses of their loved ones.[73]

Twenty-one U.S. peacekeepers who lost their lives in the bombing were buried in Section 59 at Arlington National Cemetery, near one of the memorials to all the victims.[74]

American and French response

[edit]U.S. President Ronald Reagan called the attack a "despicable act"[75] and pledged to keep a military force in Lebanon. U.S. Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, who had privately advised the administration against stationing U.S. Marines in Lebanon,[76] said there would be no change in the U.S.'s Lebanon policy. French President François Mitterrand and other French dignitaries visited both the French and American bomb sites to offer their personal condolences on Monday, October 24, 1983. It was not an official visit, and President Mitterrand only stayed for a few hours, but he did declare "We will stay."[77]

During his visit, President Mitterrand visited each of the scores of American caskets and made the sign of the cross as his mark of respectful observance for each of the fallen peacekeepers.[78] U.S. Vice President George H. W. Bush arrived and made a tour of the destroyed BLT barracks on Wednesday, October 26, 1983. Vice President Bush toured the site and said the U.S. "would not be cowed by terrorists."[77] Vice President Bush visited with wounded U.S. personnel aboard the U.S.S. Iwo Jima (LPH-2), and he took time to meet with the commanders of the other MNF units, French, Italian and British, deployed in Beirut.[79]

In retaliation for the attacks, France launched an airstrike in the Beqaa Valley against alleged Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) positions. President Reagan assembled his national security team and planned to target the Sheik Abdullah barracks in Baalbek, Lebanon, which housed Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) believed to be training Hezbollah militants.[80] A joint American–French air assault on the camp where the bombing was planned was also approved by Reagan and Mitterrand. U.S. Defense Secretary Weinberger lobbied successfully against the mission, because at the time it was not certain that Iran was behind the attack.[81]

Some of the U.S. Marines in Beirut were moved to transport vessels offshore where they could not be targeted; yet, they would be ready and available to serve as a ready reaction force in Beirut if needed.[82] For protection against snipers and artillery attacks, the Marines remaining at the airport built, and moved into, bunkers in the ground employing 'appropriated' Soviet-bloc CONEXes.[83][84]

Col. Geraghty requested and received reinforcements to replace his unit losses.[85] BLT 2/6, the Second Marine Division Air Alert Battalion stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and commanded by Col. Edwin C. Kelley, Jr., was dispatched and flown into Beirut by four C-141s in less than 36 hours after the bombing.[86] Lt. Col. Kelley officially replaced the seriously injured BLT 1/8 commander, Lt. Col. Larry Gerlach. The entire Headquarters and Service Company and Weapons Company of BLT 2/6 was airlifted into Beirut, along with Company E (Reinforced). Lt. Col. Kelley quietly redesignated his unit, BLT 2/6, as BLT 1/8 to help bolster the morale of the BLT 1/8 survivors.[87]

The BLT headquarters was relocated to a landfill area west of the airfield, and Company A (Reinforced) was repositioned from the university library position to serve as landing force reserve afloat, aboard Amphibious Ready Group shipping. On November 18, 1983, the 22d MAU rotated into Beirut and relieved in place the 24th MAU.[88] The 24th MAU with Lt. Col. Kelley commanding BLT 1/8 returned to Camp Lejeune, NC, by sea for training and refitting.

Eventually, it became evident that the U.S. would launch no serious and immediate retaliatory attack for the Beirut Marine barracks bombing beyond naval barrages and air strikes used to interdict continuous harassing fire from Druze and Syrian missile and artillery sites.[89] A true retaliatory strike failed to materialize because there was a rift in White House counsel, largely between George P. Shultz of the Department of State and Weinberger of the Department of Defense, and because the extant evidence pointing at Iranian involvement was circumstantial at that time: the Islamic Jihad, which took credit for the attack, was a front for Hezbollah which was acting as a proxy for Iran, affording Iran plausible deniability.[6]

Secretary of State Shultz was an advocate for retaliation, but Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger was against retaliation. Secretary of Defense Weinberger, in a September 2001 Frontline interview, reaffirmed that rift in White House counsel when he claimed that the U.S. still lacks "'actual knowledge of who did the bombing' of the Marine barracks."[81]

The USS New Jersey had arrived and taken up station off Beirut on September 25, 1983. Special Representative in the Middle East Robert McFarlane's team had requested New Jersey after the August 29th Druze mortar attack that killed two marines.[90] After the October 23rd bombing, on November 28, the U.S. government announced that the New Jersey would remain stationed off Beirut although her crew would be rotated. On December 14, New Jersey fired 11 projectiles from her 16-inch guns at hostile targets near Beirut. "This was the first time 16-inch shells were fired for effect anywhere in the world since the New Jersey ended her time on the gunline in Vietnam in 1969."[91] Also in December 1983, U.S. aircraft from the USS John F. Kennedy and USS Independence battle groups attacked Syrian targets in Lebanon, but this was ostensibly in response to Syrian missile attacks on American warplanes.

In the meantime, the attack boosted the prestige and growth of the Shi'ite organization Hezbollah. Hezbollah officially denied any involvement in the attacks, but was seen by many Lebanese as involved nonetheless as it praised the "two martyr mujahideen" who "set out to inflict upon the U.S. Administration an utter defeat, not experienced since Vietnam."[92] Hezbollah was now seen by many as "the spearhead of the sacred Muslim struggle against foreign occupation".[93]

The 1983 report of the U.S. Department of Defense Commission's on the attack recommended that the National Security Council investigate and consider alternative ways to reach "American objectives in Lebanon" because, "as progress to diplomatic solutions slows," the security of the USMNF base continues to "deteriorate." The commission also recommended a review for the development of a broader range of "appropriate military, political, and diplomatic responses to terrorism." Military preparedness needed improvement in the development of "doctrine, planning, organization, force structure, education, and training" to better combat terrorism, while the USMNF was "not prepared" to deal with the terrorist threat at the time due to "lack of training, staff, organization, and support" specifically for defending against "terror threats."[94]

Amal Movement leader Nabih Berri, who had previously supported U.S. mediation efforts, asked the U.S. and France to leave Lebanon and accused the two countries of seeking to commit 'massacres' against the Lebanese and of creating a "climate of racism" against Shias.[95] Islamic Jihad phoned in new threats against the MNF pledging that "the earth would tremble" unless the MNF withdrew by New Year's Day 1984.[96]

On February 7, 1984, President Reagan ordered the Marines to begin withdrawing from Lebanon largely because of waning congressional support for the mission after the attacks on the barracks.[97][98][99][100][101][102] The withdrawal of the 22d MAU from the BIA was completed 12:37 PM on February 26, 1984.[103] "Fighting between the Lebanese Army and Druze militia in the nearby Shouf mountains provided a noisy backdrop to the Marine evacuation. One officer commented: 'This ceasefire is getting louder.'"[104]

On February 8, 1984, the USS New Jersey fired almost 300 shells at Druze and Syrian positions in the Beqaa Valley east of Beirut. This was the heaviest shore bombardment since the Korean War.[citation needed] Firing without air spotting, the battleship had to rely on Israeli target intelligence.[105] "In a nine-hour period, the USS New Jersey fired 288 16-inch rounds, each one weighing as much as a Volkswagen Beetle. In those nine-hours, the ship consumed 40 percent of the 16-inch ammunition available in the entire European theater ... [and] in one burst of wretched excess," New Jersey seemed to be unleashing eighteen months of repressed fury.[106]

"Many Lebanese still recall the 'flying Volkswagens,' the name given to the huge shells that struck the Shouf."[107] In addition to destroying Syrian and Druze artillery and missile sites, approximately 30 of these behemoth projectiles rained down on a Syrian command post, killing the senior commanding Syrian general in Lebanon along with several of his senior officers.[108]

Following the lead of the U.S., the rest of the multinational force, the British, French and Italians, was withdrawn by the end of February 1984.[109][110] The ship-borne 22d MAU contingent remained stationed offshore near Beirut while a detached 100-man ready reaction force remained stationed ashore near the U.S./U.K. Embassy.[111] The 22d MAU was relieved in place by the 24th MAU on April 10, 1984. On April 21, the ready reaction force in Beirut was deactivated and its men were reassigned to their respective ships. In late July 1984, the last marines from the 24th MAU, the U.S./U.K. Embassy guard detail, was withdrawn from Beirut.[17][111]

Although the withdrawal of U.S. and French peacekeepers from Lebanon following the bombings has been widely cited as demonstrative of the efficacy of terrorism, Max Abrahms observes that the bombings targeted military personnel and as such are not consistent with the most widely accepted attempts to define terrorism, which emphasize deliberate violence against civilians.[112] A 2019 study disputes that the bombings motivated the withdrawal of U.S. forces, arguing instead that the collapse of the Lebanese national army in February 1984 was the primary motivating factor behind the withdrawal.[113]

Aftermath

[edit]Search for perpetrators

[edit]At the time of the bombing, an obscure group called the "Islamic Jihad" claimed responsibility for the attack.[114][115] There were many in the U.S. government, such as Vice President Bush, Secretary of State George Shultz, and National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane, who was formerly Reagan's Mideast envoy, who believed Iran and/or Syria were/was responsible for the bombings.[116][117] After some years of investigation, the U.S. government now believes that elements of what would eventually become Hezbollah, backed by Iran and Syria, were responsible for these bombings[115][118] as well as the bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut earlier in April.[119][120]

It is believed that Hezbollah used the name "Islamic Jihad" to remain anonymous. Hezbollah eventually announced its existence in 1985.[121][122] This is while, according to President Reagan's Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger, "We still do not have the actual knowledge of who did the bombing of the Marine barracks at the Beirut Airport, and we certainly didn't then."[14] Weinberger mentions lack of certainty about Syria or Iran's involvement as the reason why America did not take any retaliatory actions against those states.[12]

Hezbollah, Iran and Syria have continued to deny any involvement in any of the bombings. An Iranian group erected a monument in a cemetery in Tehran to commemorate the 1983 bombings and its "martyrs" in 2004.[41][123] Lebanese author Hala Jaber claims that Iran and Syria helped organize the bombing which was run by two Lebanese Shia, Imad Mughniyeh and Mustafa Badreddine:

Imad Mughniyeh and Mustafa Badr Al Din took charge of the Syrian–Iranian backed operation. Mughniyeh had been a highly trained security man with the PLO's Force 17 . . . Their mission was to gather information and details about the American embassy and draw up a plan that would guarantee the maximum impact and leave no trace of the perpetrator. Meetings were held at the Iranian embassy in Damascus. They were usually chaired by the ambassador, Hojatoleslam Ali-Akbar Mohtashemi, who played an instrumental role in founding Hezbollah. In consultation with several senior Syrian intelligence officers, the final plan was set in motion. The vehicle and explosives were prepared in the Beqaa Valley which was under Syrian control.[124]

Two years after the bombing, a U.S. grand jury secretly indicted Imad Mughniyah for terrorist activities.[125] Mughniyah was never captured, but he was killed by a car bomb in Syria on February 12, 2008.[125][126][127][128]

Commentators argue that the lack of a response by the Americans emboldened terrorist organizations to conduct further attacks against U.S. targets.[1][89] Along with the U.S. embassy bombing, the barracks bombing prompted the Inman Report, a review of the security of U.S. facilities overseas for the U.S. State Department.

On October 10, 2017 the U.S. State Department added Fuad Shukr to its Rewards for Justice Program, stating that he played a central role in the bombings.[129] Shukr was killed in an Israeli airstrike in Beirut on July 30, 2024.[130][131] Ibrahim Aqil, who also had a bounty for the same reason,[132] was killed in a separate Israeli airstrike on September 20, 2024.[133] Both assassinations took place amid the Israel–Hezbollah conflict of 2023-2024.[134][135]

Alleged retaliation

[edit]On March 8, 1985, a truck bomb blew up in Beirut, killing more than 80 people and injuring more than 200. The bomb detonated near the apartment block of Sheikh Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, a Shia cleric thought by many to be the spiritual leader of Hezbollah. Although the U.S. did not engage in any direct military retaliation to the attack on the Beirut barracks, the 1985 bombing was widely believed by Fadlallah and his supporters to be the work of the United States; Sheikh Fadlallah stating that "'They sent me a letter and I got the message,' and an enormous sign on the remains of one bombed building read: 'Made in the U.S.A.'" Robert Fisk also claims that CIA operatives planted the bomb and that evidence of this is found in an article in The Washington Post newspaper.[136]

Journalist Robin Wright quotes articles in The Washington Post and The New York Times as saying that according to the CIA the "Lebanese intelligence personnel and other foreigners had been undergoing CIA training"[137] but that "this was not our [CIA] operation and it was nothing we planned or knew about."[138] "Alarmed U.S. officials subsequently canceled the covert training operation" in Lebanon, according to Wright.[139]

Lessons learned

[edit]Shortly after the barracks bombing, President Ronald Reagan appointed a military fact-finding committee headed by retired Admiral Robert L. J. Long to investigate the bombing. The commission's report found senior military officials responsible for security lapses and blamed the military chain of command for the disaster. It suggested that there might have been many fewer deaths if the barracks guards had carried loaded weapons and a barrier more substantial than the barbed wire the bomber drove over easily. The commission also noted that the "prevalent view" among U.S. commanders was that there was a direct link between the navy shelling of the Muslims at Suq-al-Garb and the truck bomb attack.[140][141]

Following the bombing and the realization that insurgents could deliver weapons of enormous yield with an ordinary truck or van, the presence of protective barriers (bollards) became common around critical government facilities in the United States and elsewhere, particularly Western civic targets situated overseas.[142]

A 2009 article in Foreign Policy titled "Lesson Unlearned" argues that the U.S. military intervention in the Lebanese Civil War has been downplayed or ignored in popular history – thus unlearned – and that lessons from Lebanon are "unlearned" as the U.S. militarily intervenes elsewhere in the world.[143]

Civil suit against Iran

[edit]On October 3 and December 28, 2001, the families of the 241 U.S. peacekeepers who were killed as well as several injured survivors filed civil suits against the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Ministry of Information and Security (MOIS) in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.[144] In their separate complaints, the families and survivors sought a judgment that Iran was responsible for the attack and relief in the form of damages (compensatory and punitive) for wrongful death and common-law claims for battery, assault, and intentional infliction of emotional distress resulting from an act of state-sponsored terrorism.[144]

Iran, the defendant, was served with the two complaints, one from Deborah D. Peterson, Personal Representative of the Estate of James C. Knipple, et al., the other from Joseph and Marie Boulos, Personal Representatives of the Estate of Jeffrey Joseph Boulos, on May 6 and July 17, 2002.[144] Iran denied responsibility for the attack[145] but did not file any response to the claims of the families.[144] On December 18, 2002, Judge Royce C. Lamberth entered defaults against defendants in both cases.[144]

On May 30, 2003, Lamberth found Iran legally responsible for providing Hezbollah with financial and logistical support that helped them carry out the attack.[144][146] Lamberth concluded that the court had personal jurisdiction over the defendants under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, that Hezbollah was formed under the auspices of the Iranian government and was completely reliant on Iran in 1983, and that Hezbollah carried out the attack in conjunction with MOIS agents.[144]

On September 7, 2007, Lamberth awarded $2,656,944,877 to the plaintiffs. The judgment was divided up among the victims; the largest award was $12 million to Larry Gerlach, who became a paraplegic as a result of a broken neck he suffered in the attack.[147]

The attorney for the families of the victims uncovered some new information, including a U.S. National Security Agency intercept of a message sent from Iranian intelligence headquarters in Tehran to Hojjat ol-eslam Ali-Akbar Mohtashemi, the Iranian ambassador in Damascus. As it was paraphrased by presiding U.S. District Court Judge Royce C. Lamberth, "The message directed the Iranian ambassador to contact Hussein Musawi, the leader of the terrorist group Islamic Amal, and to instruct him ... 'to take a spectacular action against the United States Marines.'"[148]

Musawi's Islamic Amal was a breakaway faction of the Amal Movement and an autonomous part of embryonic Hezbollah.[149] According to Muhammad Sahimi, high-ranking US officials had a different interpretation from that intercept, which stopped them from ordering a revengeful attack against Iran.[14]

In July 2012, federal Judge Royce Lamberth ordered Iran to pay more than $813m in damages and interest to the families of the 241 U.S. peacekeepers that were killed, writing in a ruling that Tehran had to be "punished to the fullest extent legally possible... Iran is racking up quite a bill from its sponsorship of terrorism."[150][151][152][153] In April 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that frozen assets of Iran's Central Bank held in the U.S. could be used to pay the compensation to families of the victims.[154]

Mossad conspiracy theory

[edit]Former Mossad agent Victor Ostrovsky, in his 1990 book By Way of Deception, has accused the Mossad of knowing the specific time and location of the bombing, but only gave general information to the Americans of the attack, information which was worthless. According to Ostrovsky, then Mossad head Nahum Admoni decided against giving the specific details to the Americans on the grounds that the Mossad's responsibility was to protect Israel's interests, not Americans. Admoni denied having any prior knowledge of the attack.[155]

Benny Morris, in his review of Ostrovsky's book, wrote that Ostrovsky was "barely a case officer before he was fired; most of his (brief) time in the agency was spent as a trainee" adding that due to compartmentalization "he did not and could not have had much knowledge of then current Mossad operations, let alone operational history." Benny Morris wrote that the claim regarding the barracks was "odd" and an example of one of Ostrovsky's "wet" stories which were "mostly fabricated."[156]

Memorials and remembrance

[edit]

A Beirut Memorial has been established at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, and has been used as the site of annual memorial services for the victims of the attack.[157] A Beirut Memorial Room at the USO in Jacksonville, North Carolina has also been created.[158]

The Armed Forces Chaplaincy Center, the site of Chaplain Corps training for the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Force at Fort Jackson, Columbia, South Carolina, includes the partially destroyed sign from the Beirut barracks chapel as a memorial to those who died in the attack.[159] According to Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, one of the navy chaplains present during the attack, "Amidst the rubble, we found the plywood board which we had made for our "Peace-keeping Chapel." The Chaplain Corps Seal had been hand-painted, with the words "Peace-keeping" above it, and "Chapel" beneath. Now "Peace-keeping" was legible, but the bottom of the plaque was destroyed, with only a few burned and splintered pieces of wood remaining. The idea of peace – above; the reality of war – below."[159]

Other memorials to the victims of the Beirut barracks bombing have been erected in various locations within the U.S., including one at Penn's Landing in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Boston, Massachusetts, and one in Florida.[160] A Lebanese cedar has been planted in Arlington National Cemetery near the graves of some of the victims of the attack, in their memory. A plaque in the ground in front of the tree, dedicated in a ceremony on the first anniversary of the attack, reads: "Let peace take root: This cedar of Lebanon tree grows in living memory of the Americans killed in the Beirut terrorist attack and all victims of terrorism around the world." The National Museum of the Marine Corps, in Quantico, Virginia, unveiled an exhibit in 2008 in memory of the attack and its victims.[161]

One memorial to the attack is located outside the U.S., where Gilla Gerzon, the director of the Haifa, Israel USO during the time of the attack coordinated the creation of a memorial park that included 241 olive trees, one for each of the U.S. military personnel who died in the attack.[162] The trees lead to an overpass on Mount Carmel looking toward Beirut.[162][163]

In 2004 it was reported that an Iranian group called the Committee for the Commemoration of Martyrs of the Global Islamic Campaign had erected a monument, at the Behesht-e-Zahra cemetery in Tehran, to commemorate the 1983 bombings and its "martyrs".[41][123]

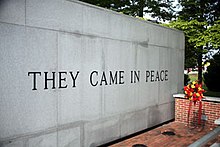

There is also an ongoing effort on the part of Beirut veterans and family members to convince the U.S. Postal Service and Citizens' Stamp Advisory Committee to create a stamp in memory of the victims of the attack, but the recommendation has not yet been approved.[164][165] In the meantime, Beirut veterans have created a "PC Postage" commercially produced Beirut Memorial statue private vendor stamp (with or without the words "They Came in Peace") that is approved for use as postage by the U.S. Postal Service.[165]

Author and former Navy SEAL Jack Carr announced that he would be writing a book about the 1983 bombings, entitled Targeted, which is set for release in late 2024.[166]

See also

[edit]- 1983 US embassy bombing in Beirut

- Tyre headquarters bombings, similar attacks against Israeli military posts in Lebanon

- 1984 United States embassy annex bombing

- Khobar Towers Bombing

- Mountain War

- List of vehicle ramming terrorist attacks

- Front for the Liberation of Lebanon from Foreigners (FLLF)

- 2021 Kabul airport attack

Notes

[edit]- ^ For Iran's threat of retaliatory measures; see Ettela'at, 17 September 1983; Kayhan, 13 October 1983; and Kayhan, 26 October 1983, quoted in Ranstorp, Magnus, Hizb'allah in Lebanon : The Politics of the Western Hostage Crisis, New York, St. Martins Press, 1997, p. 117

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Geraghty (2009), p. xv

- ^ Phillips, James (October 23, 2009). "The 1983 Marine Barracks Bombing: Connecting the Dots". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 386.

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 394.

- ^ "Part 8 – Casualty Handling". Report of the DoD Commission on Beirut International Airport Terrorist Act, October 23, 1983. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Peterson v. Islamic Republic of Iran, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia" (PDF). Perles Law Firm. Washington, DC. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2006. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c Geraghty (2009), pp. 185–186

- ^ a b "Report of the DoD Commission on Beirut International Airport Terrorist Attack, October 23, 1983" (PDF). December 20, 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ Wright, Robin, Sacred Rage, Simon and Schuster, 2001, p. 72

- ^ a b "On This Day: October 23". The New York Times. October 23, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Stephens, Bret (October 22, 2012). "Stephens: Iran's Unrequited War". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 24, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ a b "target america". Frontline. WGBH. October 4, 2001. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "now.mmedia.me 30 October 2014". Archived from the original on August 3, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The Fog over the 1983 Beirut Attacks". FRONTLINE - Tehran Bureau. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ New York Times, Page 1, September 20, 1982

- ^ New York Times, Page 1, September 21, 1982

- ^ a b c Frank, Benis M. (1987). "US Marines In Lebanon 1982–1984" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 1–6

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 88

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 3–9, 11–12.

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), pp. 87–88

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 192

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 91

- ^ a b Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 95

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 6

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 33.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 5–7

- ^ Fisk, Robert (2002). Pity the Nation: The Abduction of Lebanon. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1560254423.

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 276–277.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 57, 152

- ^ a b c d e f g DOD Commission on Beirut International Airport December 1983 Terrorist Act Archived July 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Agostino von Hassell (October 2003). "Beirut 1983: Have We Learned This Lesson?". Marines Corps Gazette. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 165

- ^ Anthony H. Cordesman, The Iran-Iraq war and Western Security, 1984–1987: Strategic Implications and Policy Options, Janes Publishing Company, 1987

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 77, 185

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 78

- ^ a b Geraghty (2009), pp. 183–185

- ^ "The civilian infrastructure established by Hezbollah among the Shiite population: the city of Nabatieh as a case study" (PDF). Meir Amit Terrorism and Intelligence Center. January 1, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), pp. xxii, 125, 392

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b c Geraghty (2009), p. 185

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 306.

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 303.

- ^ Time Magazine Jan 2, 1984 "Beirut: Serious Errors in Judgment" Archived January 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paul Rogers(2000)"Politics in the Next 50 Years: The Changing Nature of International Conflict Archived March 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ a b c d e Geraghty (2009), p. 188

- ^ "1st Parachute Regiment, Third Company". French Army. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "Carnage in Lebanon". Time. October 31, 1983. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 329

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 334

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 338–339

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 331–332

- ^ [1] Archived June 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 95–96, 99

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 353

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 366–367

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 101

- ^ a b Hammel (1985), pp. 353–395

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 104

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 349, 377, 388

- ^ a b Geraghty (2009), p. 99

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 350

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 101–104

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 378–395

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 100–101

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 381–382

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 376, 387–388

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 388

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 386

- ^ a b Cpl. Chelsea Flowers Anderson (October 22, 2012). "The Impact of the Beirut Bombing". Official Blog of the United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on May 26, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Frykberg, E. R.; Tepas, J. J.; Alexander, R. H. (March 1989). "The 1983 Beirut Airport terrorist bombing. Injury patterns and implications for disaster management". The American Surgeon. 55 (3): 134–141. ISSN 0003-1348. PMID 2919835.

- ^ "Pentagon List of Casualties from Bombing in Beirut". The New York Times. AP. October 26, 1983. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ "Marines Are Releasing Bomb Survivors' Names". Washington Post. October 27, 1983. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ "Beirut Barracks Bombing – October 23, 1983". Arlington National Cemetery. 2018. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas E. "Beirut Death Toll at 161 Americans; French Casualties Rise in Bombings; Reagan Insists Marines Will Remain," in The New York Times

- ^ Weinberger, Caspar (2001). "Interview: Caspar Weinberger". Frontline. PBS. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ a b Harris, S. (2010) The watchers: the rise of America's surveillance state, Penguin. ISBN 978-1594202452

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 107–108

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 111–112

- ^ Bates, John D. (Presiding) (September 2003). "Anne Dammarell et al. v. Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). District of Columbia, U.S.: The United States District Court for the District of Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ^ a b "Terrorist Attacks On Americans, 1979–1988". Frontline. PBS. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 409–419

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 147

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 405–406, 421

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 94, 109, 111

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 401–402

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 402–403

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 421

- ^ a b McFarlane, Robert C., "From Beirut To 9/11 Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine", The New York Times, October 23, 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), pp. 115–116

- ^ "History". Battleship New Jersey. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ quote from FBIS, August 1994, quoted in Ranstorp, Hizb’allah in Lebanon (1997), p. 38

- ^ Ranstorp, Magnus (1997). Hizb'allah in Lebanon: the politics of the western hostage crisis. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 38. ISBN 978-0312164911. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "Report of the DoD commission on Beirut International Airport terrorist act Archived May 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, December 20, 1983

- ^ statement from November 22, 1983. Wright, Sacred Rage, (2001), p. 99

- ^ statement from December 1983, from Wright, Sacred Rage, (2001), p. 99

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (October 29, 1983). "O'neill Criticizes President; War Powers Act Is Invoked". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Tolchin, Martin (January 27, 1984). "O'neill Predicts House Will Back Resolution On Lebanon Pullout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (February 1, 1984). "House Democrats Draft Resolution On Beirut Pullout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), pp. 144–150

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 162

- ^ Hammel (1985), p. 423

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 152

- ^ "US role in Beirut goes on despite exit of marines from peace force". Christian Science Monitor. February 27, 1984. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ "Officer returns to battleship". www.southjerseynews.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 151

- ^ "U.S. warship stirs Lebanese fear of war". Christian Science Monitor. March 4, 2008. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Navy Battleships – USS New Jersey (BB 62)". Navy.mil. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 179

- ^ Hammel (1985), pp. 423–425

- ^ a b Hammel (1985), p. 425

- ^ Abrahms, Max (2018). Rules for Rebels: The Science of Victory in Militant History. Oxford University Press. pp. 42–44. ISBN 9780192539441.

- ^ "When Do Leaders Change Course? Theories of Success and the American Withdrawal from Beirut, 1983–1984". Texas National Security Review. March 28, 2019. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 197

- ^ a b Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 133

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 172, 195–197, 209

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), pp. 132–133

- ^ Morley, Jefferson (July 17, 2006). "What Is Hezbollah?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 190

- ^ Martin & Walcott (1988), p. 363

- ^ Goldberg, Jeffrey (October 14, 2002). "A Reporter At Large: In The Party Of God (Part I) – Are terrorists in Lebanon preparing for a larger war?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. xv, 181

- ^ a b "جنبش غیرمتعهدها رای دیوان عالی آمریکا در مورد اموال مسدود شده ایران را مردود دانست". BBC News فارسی. May 6, 2016. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ Jaber, Hala. Hezbollah: Born with a Vengeance, New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. p. 82

- ^ a b "Bomb kills top Hezbollah leader". BBC News. February 13, 2008. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Hampson, Rick, "25 Years Later, Bombing In Beirut Still Resonates Archived July 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", USA Today, October 16, 2008, p. 1.

- ^ "Hezbollah Militant Accused of Plotting Attacks Killed". NPR.org. NPR. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), p. 191

- ^ "Rewards for Justice – Reward Offer for Information on Hizballah Key Leaders Talal Hamiyah and Fu'ad Shukr". October 11, 2017. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020.

- ^ "IDF target Hezbollah commander responsible for Majdal Shams attack". Ynet. July 30, 2024. Archived from the original on August 18, 2024. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Source close to Hezbollah says body of top commander killed in Israeli strike found". gulfnews.com. July 31, 2024. Archived from the original on July 31, 2024. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ "Ibrahim Aqil – Rewards For Justice". Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ "Who was Ibrahim Aqil? The slain Hezbollah commander wanted for '83 Beirut barracks blast". The Times of Israel. September 20, 2024. Retrieved September 20, 2024.

- ^ Kaufman, Asher (September 22, 2024). "A weakened Hezbollah is being goaded into all-out conflict with Israel – the consequences would be devastating for all". The Conversation. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ "Israel Targets Hezbollah & Hamas Officials | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Robert Fisk, Pity the Nation, 1990, p. 581, paragraph 4

- ^ The Washington Post, May 12, 1985

- ^ The New York Times may 13, 1985

- ^ Wright, Robin, Sacred Rage : The Wrath of Militant Islam, Simon and Schuster, 2001 p. 97.

- ^ "20 Years Later: Nothing Learned, So More American Soldiers Will Die by James Bovard, October 23, 2003". Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Geraghty (2009), pp. 138–150

- ^ "Hospital ships in the war on terror: sanctuaries or targets? | Naval War College Review | Find Articles at BNET". Findarticles.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ Nir Rosen (October 29, 2009). "Lesson Unlearned". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Memorandum Opinion Archived January 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine (Royce C. Lambert, judge), Deborah D. Peterson, Personal Representative of the Estate of James C. Knipple, et al., v. the Islamic Republic of Iran, et al. (Civil Action No. 01-2684 (RCL)) and Joseph and Marie Boulos, Personal Representatives of the Estate of Jeffrey Joseph Boulos v. the Islamic Republic of Iran, et al. (2003).

- ^ "Iran must pay $2.6 billion for attack on U.S. Marines, judge rules." CNN September 7, 2007. Archived July 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Iran responsible for 1983 Marine barracks bombing, judge rules. CNN May 30, 2003. Archived June 4, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kessler, Glenn. "Iran Must Pay $2.6 Billion for '83 Attack Archived April 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine." The Washington Post September 8, 2007.

- ^ Timmerman, Kenneth R. (December 22, 2003). "Invitation to September 11". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ "Lebanon: Islamic Amal". Country Studies. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ "US orders Iran to pay for 1983 Lebanon attack – Americas". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. court fines Iran $813 mn for 1983 Lebanon attack". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Breaking News". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. court fines Iran $813 million for 1983 Lebanon attack". Al Arabiya. July 7, 2012. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "Iran funds can go to US Beirut blast victims – Supreme Court". BBC News. April 20, 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ^ Kahana, Ephraim (2006). Historical dictionary of Israeli intelligence. Vol. 3. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 4. ISBN 978-0810855816. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Morris, Benny (1996). "The Far Side of Credibility, Benny Morris". Journal of Palestine Studies. 25 (2): 93–95. doi:10.1525/jps.1996.25.2.00p0105y. JSTOR 2538192.

- ^ Memorial description, Camp Lejeune website Archived February 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Description of the USO Beirut Memorial Room, from www.beirutveterans.org Archived February 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 15, 2011l.

- ^ a b Resnicoff, Arnold, "With the Marines in Beirut," "The Jewish Spectator," Fall 1984 Archived January 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ List of memorials on Beirut Memorial website Archived August 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Serena Jr., Jimmy, LCpl, "Quantico remembers Beirut," dcmilitary.com, October 23, 2008 Archived April 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "The Mother of the Sixth Fleet," July 23, 2006 Archived January 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Kolb, Richard K., "Armegeddon: The Holy Land as Battlefield," VFW Magazine, September 1, 2000 Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Description of effort to create stamp, from www.beirut-documentary.org site Archived January 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Baines, Christopher, Pfc, "Beirut veterans, fallen, honored with memorial stamp," August 6, 2010 Archived January 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ Baimbridge, Richard (September 14, 2023). "Navy SEAL Jack Carr's 8-Point Guide to Writing a Bestseller". aarp.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Geraghty, Timothy J. (2009). Peacekeepers at War: Beirut 1983 – The Marine Commander Tells His Story. With a foreword by Alfred M. Gray, Jr. (1st ed.). Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1597974257. OCLC 759525242.

- Hammel, Eric M. (1985). The Root: The Marines in Beirut, August 1982 – February 1984. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0151790067. OCLC 11677008.

- Martin, David C.; Walcott, John (1988). Best Laid Plans: The Inside Story of America's War Against Terrorism. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060158774.

Further reading

[edit]- Dolphin, Glenn E. (2005). 24 MAU 1983: A Marine Looks Back at the Peacekeeping Mission to Beirut, Lebanon. Publish America. ISBN 978-1413785012.

- Frank, Benis M. (1987). U.S. Marines in Lebanon, 1982–1984. U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- Petit, Michael (1986). Peacekeepers at War: A Marine's Account of the Beirut Catastrophe. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0571125456.

- Pivetta, Patrice (2014). Beyrouth 1983, la 3e compagnie du 1er RCP dans l'attentat du Drakkar. Militaria Magazine 342, January 2014, pp. 34–45. (in French).

External links

[edit]- President Reagan reads Chaplain Arnold Resnicoff's first-hand account of bombing: Text Version; Video Version; Text of original report,[dead link]

- Tribute to the French 3rd Parachute Company

- Lebanese civil war Full Information Archived November 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- 241.SaveTheSoldiers.com An Honorary Tribute to the soldiers who died

- Lebanese civil war 1983 Full of Pictures and Information[usurped]

- John H. Kelly : Lebanon 1982–1984 – includes Diary entries by Ronald Reagan: " I have ordered the use of Naval Gunfire. " – September 11, 1983

- Report on the bombing

- Aftermath pictures

- The Beirut Memorial Online

- BeirutCoin.com – Commemorative Challenge Coin honoring those KIA

- Official Beirut Veterans of America Website

- "A Soldier's Perspective: Remembering America's First Suicide Bombing, Oct 20, 2008.

- A chaplain remembers: brief YouTube interview with Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, recalling attack and its aftermath.

- "Finding Accommodation," Washington Jewish Week, Oct 23, 2008. Looking back 25 years at lessons of interfaith cooperation from the bombing.

- Extensive CBS Radio breaking newscast recordings

- Richmond Times Dispatch online presentation

- 30th Anniversary of the Beirut Bombing Archived September 28, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- 1983 in international relations

- Massacres in 1983

- Ministry of Intelligence (Iran)

- Attacks on military installations in 1983

- Cold War military history of France

- France–Iran relations

- France–Lebanon relations

- Hezbollah

- 1983 in the United States

- Iran–United States relations

- Iran–Lebanon relations

- Lebanon–United States relations

- Massacres of the Lebanese Civil War

- October 1983 events in Asia

- Reagan administration controversies

- Suicide bombings in 1983

- Suicide bombings in Beirut

- Suicide car and truck bombings in Lebanon

- Anti-American sentiment in the Middle East

- United States Marine Corps in the 20th century

- Building bombings in Beirut

- 1983 murders in Lebanon

- 20th-century mass murder in Lebanon

- Terrorist incidents in Lebanon in 1983

- Hezbollah attacks

- Beirut in the Lebanese Civil War

- 1980s crimes in Beirut

- 1983 building bombings

- Attacks on military installations in Lebanon

- Attacks on barracks

- Cold War military history of the United States