Military settlement

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Military settlements (Russian: Военные поселения) represented a special organization of the Russian military forces in 1810–1857, which allowed the combination of military service and agricultural employment.

The beginning of the reform

[edit]The Emperor Alexander I of Russia (reigned 1801-1825) introduced military settlements in order to set up an inexpensive reserve of trained military forces. Count Alexei Arakcheyev, who had held senior military and political appointments, established the first military settlement (1810-1812) in the Klimovichskiy Uyezd of the Mogilev Governorate (in present-day Belarus). The organization of military settlements got under way on a large scale from 1816. In 1817 Count Arakcheyev officially became the head of all the military settlements (Russian: начальника военных поселений) in Russia.

Internal organization

[edit]The quartered military forces were being formed from among married soldiers, who had already served in the army for no less than six years, and local men (mainly, peasants) between 18 and 45 years of age. Both of these categories were called master settlers (поселяне-хозяева). The rest of the locals of the same age, who had been fit for military service, but had not been chosen, were being enlisted as assistants to their masters and were a part of reserve military subdivisions.

The children (under age of 18) of the military settlers and the indigenous peasant population within the military settlement were enlisted in the cantonists, with military schooling starting at the age of 7 (later changed to 10). Upon reaching the age of 18, they were transferred to the military units. The settlers would retire at the age of 45 and continue to serve in hospitals and other establishments.[1]

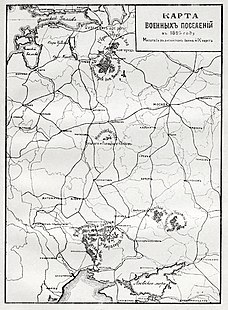

Each military settlement consisted of 60 interconnected houses (дома-связи) with a regiment of 228 men. Each such house had four masters with indivisible household economy. The life in a military settlement was strictly controlled. In fact military settlers did not live in these rather comfortable specially built interconnected houses (svyaz), because they were built only to be shown to higher military officials as a proof that the Emperor’s wish had been fully accomplished. Military settlers found shelter in small side houses. The internal regulations enforced by Arakcheyev strictly prohibited any residents to be inside of these houses. If someone had been seen inside a living apartment of the house, he was subject to immediate severe corporal punishment. It was restricted to use or even touch pots and similar household things inside living parts of the houses. The Arakcheyev’s instructions strictly prescribed that each pot must be placed on the specified place inside the house. If a pot was removed from its place, military resident of the respective house was punished. The peasants had to undergo military training, which caused tardiness and unseasonableness in agricultural activities. Corporal punishment was common. Military settlements were being created on fiscal lands (казённые земли), which would often provoke riots among the state-owned peasants (казённые крестьяне), like the ones in Kholynskaya and Vysotskaya volosts of the Novgorod guberniya in 1817 and among the Bug Cossacks in 1817–1818. Alexander I, however, stood his ground and announced that "military settlements will be created, even if we have to pave the road from Saint Petersburg to Chudov [today’s Chudovo; some 100 km (62 mi) away from Petersburg] with dead bodies". By 1825, Russia had already built military settlements in Petersburg, Novgorod (along the Volkhov River and near Staraya Russa[2]), Mogilev, Sloboda Ukraine, Kherson, Ekaterinoslav and other guberniyas. They made up for almost one fourth of the Russian army (one third, according to other accounts) and accumulated some 32 million rubles worth of savings, but still were not able to satisfy the army’s recruiting needs.

Organization of rural and agriculture activities was extremely bad. All the activities of military settlers were strictly specified by Arakcheyev’s instructions. These instructions paid little attention to season character of certain works or distance between military settlement and fields to be plowed. For example, sometimes it may be prescribed to make hay 7–10 miles away from the military settlement. Settlers had to spend a lot of time to get to their job and then back, so the work could not be done in time. If an instruction was not complied with, all the settlers had been severely punished no matter what reason they had for not to do the job in time. Sometimes the instruction strictly specified a certain day for a certain job, and if it was rainy at such day, the job could not be done. Since the instruction was not complied again, settlers got severe punishment. State officials including Arakcheyev knew little about agriculture. In Saint Petersburg area peasants had been practicing hunting, fishing, small artisan production, trade activities for a long time, because northern soil did not fit for agriculture. When military settlements had been implemented near Saint Petersburg, all the settlers had been prescribed to grow wheat and other activities out of law, this led to impoverishment of local population and malnourishment. Due to such circumstances the military performance of settlers was low. Overall, they were not effective as soldiers or agriculture workers.

Riots in military settlements

[edit]Military settlements never became an anti-resistance tool in the hands of the government, on the contrary, they turned into resistance hotbeds themselves. In June 1819, the Chuguyev regiment uprising took place amidst the Sloboda Ukraine military settlement, which would then spread over to the Taganrog regiment okrug a month later. The rebels were demanding from the government to let them be what they had been before the reform, capturing their confiscated lands, beating, and ousting their superiors. Count Arakcheyev was put in charge of the punitive expedition, which would result in the arrest of more than 2,000 men. 313 people were subjected to military tribunal, 275 of which (204, according to other accounts) would be sentenced to corporal punishment by 12,000 strikes each with metal rods. 25 men are known to have died during the execution of this sentence; the rest were transferred to Orenburg.

In July 1831, one of the largest military riots in the Russian army of the 1st half of the 19th century took place in a military settlement near Staraya Russa. It was caused by cholera outbreak, which would in turn provoke a number of "cholera riots". The military settlement was overrun by the rebels, who then court-martialed their superiors and executed them. The rebellion spread over the majority of military settlements of the Novgorod guberniya. The battalion, sent by the government to pacify the rebels, took the side of the insurgents. Soon, the authorities suppressed the uprising and severely punished those who took part in it. A third of the local villagers who had participated in the rebellion were subjected to running the gauntlet and exiled to Siberia. Many people were sent to katorga to the fortress of Kronstadt.

Abolition

[edit]In 1831, many military settlements were renamed to communities of plowing soldiers (округа пахотных солдат), which would lead to an actual elimination of most of the military settlements. In 1857, all of the military settlements and okrugs of the plowing soldiers were abolished.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Туркестанов, Н.Х. (1871). Граф Аракчеев и военные поселения 1809-1831 [Count Arakcheev and military settlements 1809-1831] (in Russian). pp. https://books.google.com/books?id=cB8HAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA109 109. ISBN 5518040083.

- ^ a b Снытко, О.В.; et al. (2009). Трифонов, С.Д.; Чуйкова, Т.Б.; Федина, Л.В.; Дубоносова, А.Э. (eds.). Административно-территориальное деление Новгородской губернии и области 1727-1995 гг. Справочник [Administrative-territorial division of the Novgorod province and region 1727-1995. Reference] (PDF) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg. p. 26. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)