Mixolydian mode

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Mixolydian mode may refer to one of three things: the name applied to one of the ancient Greek harmoniai or tonoi, based on a particular octave species or scale; one of the medieval church modes; or a modern musical mode or diatonic scale, related to the medieval mode. (The Hypomixolydian mode of medieval music, by contrast, has no modern counterpart.)

The modern diatonic mode is the scale forming the basis of both the rising and falling forms of Harikambhoji in Carnatic music, the classical music form of southern India, or Khamaj in Hindustani music, the classical music form of northern India.

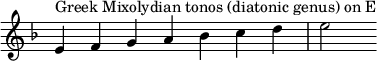

Greek Mixolydian[edit]

The idea of a Mixolydian mode comes from the music theory of ancient Greece. The invention of the ancient Greek Mixolydian mode was attributed to Sappho, the 7th-century-B.C. poet and musician.[1] However, what the ancient Greeks thought of as Mixolydian is very different from the modern interpretation of the mode. The prefix mixo- (μιξο-) means "mixed", referring to its resemblance to the Lydian mode.

In Greek theory, the Mixolydian tonos (the term "mode" is a later Latin term) employs a scale (or "octave species") corresponding to the Greek Hypolydian mode inverted. In its diatonic genus, this is a scale descending from paramese to hypate hypaton: in the diatonic genus, a whole tone (paramese to mese) followed by two conjunct inverted Lydian tetrachords (each being two whole tones followed by a semitone descending). This diatonic genus of the scale is roughly the equivalent of playing all the white notes of a piano from B to B, which is also known as modern Locrian mode.

In the chromatic and enharmonic genera, each tetrachord consists of a minor third plus two semitones, and a major third plus two quarter tones, respectively.[2]

Medieval Mixolydian and Hypomixolydian[edit]

The term Mixolydian was originally used to designate one of the traditional harmoniai of Greek theory. It was appropriated later (along with six other names) by 2nd-century theorist Ptolemy to designate his seven tonoi or transposition keys. Four centuries later, Boethius interpreted Ptolemy in Latin, still with the meaning of transposition keys, not scales.

When chant theory was first being formulated in the 9th century, these seven names plus an eighth, Hypermixolydian (later changed to Hypomixolydian), were again re-appropriated in the anonymous treatise Alia Musica. A commentary on that treatise, called the Nova expositio, first gave it a new sense as one of a set of eight diatonic species of the octave, or scales.[3] The name Mixolydian came to be applied to one of the eight modes of medieval church music: the seventh mode. This mode does not run from B to B on white notes, as the Greek mode, but was defined in two ways: as the diatonic octave species from G up one octave to the G above, or as a mode whose final was G and whose ambitus runs from the F below the final to the G above, with possible extensions "by licence" up to A above and even down to E below, and in which the note D (the tenor of the corresponding seventh psalm tone) had an important melodic function.[4] This medieval theoretical construction led to the modern use of the term for the natural scale from G to G.

The seventh mode of western church music is an authentic mode based on and encompassing the natural scale from G to G, with the perfect fifth (the D in a G to G scale) as the dominant, reciting note or tenor.

The plagal eighth mode was termed Hypomixolydian (or "lower Mixolydian") and, like the Mixolydian, was defined in two ways: as the diatonic octave species from D to the D an octave higher, divided at the mode final, G (thus D–E–F–G + G–A–B–C–D); or as a mode with a final of G and an ambitus from C below the final to E above it, in which the note C (the tenor of the corresponding eighth psalm tone) had an important melodic function.[5]

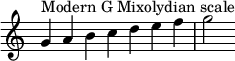

Modern Mixolydian[edit]

The modern Mixolydian scale is the fifth mode of the major scale (Ionian mode). That is, it can be constructed by starting on the fifth scale degree (the dominant) of the major scale. Because of this, the Mixolydian mode is sometimes called the dominant scale.[6]

This scale has the same series of tones and semitones as the major scale, but with a minor seventh. As a result, the seventh scale degree is a subtonic, rather than a leading-tone.[7] The flattened seventh of the scale is a tritone away from the mediant (major-third degree) of the key. The order of whole tones and semitones in a Mixolydian scale is

- whole, whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole

In the Mixolydian mode, the tonic, subdominant, and subtonic triads are all major, the mediant is diminished, and the remaining triads are minor. A classic Mixolydian chord progression is I-♭VII-IV-V.[8]

The Mixolydian mode is common in non-classical harmony, such as folk, jazz, funk, blues, and rock music. It is often prominently heard in music played on the Great Highland bagpipes.

[In the blues progression, for] example [often] uses D Mixolydian triads...over the D7 [tonic] chord, then uses G Mixolydian triads...over the G7 [subdominant] chord, and so on.[9]

As with natural and harmonic minor, Mixolydian is often used with a major seventh degree as a part of the dominant and perfect cadences. "Wild Thing" by The Troggs is a, "perfect example," while others include "Tangled Up in Blue" by Bob Dylan, "Shooting Star" by Bad Company, and "Bold as Love" by Jimi Hendrix.[8]

Klezmer musicians refer to the Mixolydian scale as the Adonai malakh mode. In Klezmer, it is usually transposed to C, where the main chords used are C, F, and G7 (sometimes Gm).[10]

To hear a modern Mixolydian scale, one can play a G-major scale on the piano, but change the F# to F natural.

Notable music in Mixolydian mode[edit]

Hit songs in Mixolydian include "Paperback Writer"..., "Manic Depression"..., "Fire"..., "Reelin' in the Years"..., "Only You Know and I Know"..., "Tears of a Clown"..., "Don't Stop 'til You Get Enough"..., "Norwegian Wood"..., "Saturday Night's Alright..., "My Generation"..., "Centerfold"..., "Boogie Fever"..., "Hollywood Nights"..., and many others.[11]

Some song examples that are either entirely based in Mixolydian mode or at least have a Mixolydian section include the following: "But Anyway"..., "Cinnamon Girl"..., "Cult of Personality"..., "Fire on the Mountain"..., "Franklin's Tower"..., "Get Down Tonight".[12]

Traditional[edit]

- "Old Joe Clark"[13][14][15][16]

- "Gleanntáin Ghlas' Ghaoth Dobhair" (English: Gweedore's Green Glens), also called "Paddy's Green Shamrock Shores" – A traditional Irish folk song, composed by Francie Mooney (Proinsias Ó Maonaigh).[17][18] Recorded by the band Altan, with Mooney's daughter Mairéad on lead vocals, on their album Runaway Sunday (1997). Recorded by The Corrs as "Erin Shore" on their album Forgiven Not Forgotten (1995).

- "She Moved Through the Fair" – A traditional Irish folk song.[19] Sometimes called "Our Wedding Day" and sung with different lyrics, such as by vocalist Anne Buckley in Michael Flatley's Lord of the Dance (1996).

- "The Wexford Carol"

- "Green Bushes"

- And countless Irish, Scottish and Cape Breton jigs, reels, highlands and other dance tunes recorded in the mode.

Classical[edit]

- "Fughetta super: Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot" in G major from Clavier-Übung III, BWV 679 by Johann Sebastian Bach[20][21]

- Piano Concerto in A minor, third movement, by Edvard Grieg[20]

- Concerto in modo misolidio, P 145 (1925) by Ottorino Respighi[22][21]

- Et resurrexit from Beethoven's Missa solemnis

- Surgam et circuibo civitatem by Palestrina[21]

Popular[edit]

- "Sweet Child O’ Mine" by Guns N' Roses[23]

- "Thunderstruck" by AC/DC[24]

- "You Really Got Me" by The Kinks[25]

- "I Feel Fine" by The Beatles[26]

- "Love Shack" by The B-52’s

- "Express Yourself" by Madonna[27]

- "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" by John Lennon and Paul McCartney[28][11]

- "Royals" by Lorde[29][21]

- "Born This Way" by Lady Gaga[30]

- "Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)" by Beyoncé[31]

- "Shake It Off" by Taylor Swift[32]

- "Clocks" by Coldplay[33][21][34]

- "Be Near Me" and "When Smokey Sings" by ABC

- "Freedom! '90" by George Michael

- "Happy Together" by The Turtles[35]

- "Beautiful" by Christina Aguilera

- "Epistrophy" by Thelonious Monk[36]

- "Celebration" by Kool & the Gang

- "Freedom Jazz Dance" by Eddie Harris[36]

- "Dark Star" by Grateful Dead[21][34]

- "L.A. Woman" by The Doors[21][34]

- "All Blues" by Miles Davis[21]

- "If I Needed Someone" by The Beatles[34]

- "Yes, And?" by Ariana Grande

- "Unwritten" by Natasha Bedingfield

- "Marquee Moon" by Television[34]

- "Sweet Home Alabama" by Lynyrd Skynyrd[34]

- "Collision Chaos" from Sonic CD

- "Revelation Song" by Jennie Lee Riddle[37][38]

See also[edit]

- Harikambhoji, the equivalent scale in Carnatic music.

- Khamaj, the equivalent scale in Hindustani music.

- V–IV–I turnaround, a common modal chord progression when spelled as I–♭VII–IV[citation needed]

- Backdoor cadence

References[edit]

- ^ Anne Carson (ed.), If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho (New York: Vintage Books, 2002), p. ix. ISBN 978-0-375-72451-0. Carson cites Pseudo-Plutarch, On Music 16 (1136c Steph.), who in turn names Aristoxenus as his authority.

- ^ Thomas J. Mathiesen, "Greece", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell, (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001), 10:339. ISBN 1-56159-239-0 OCLC 44391762.

- ^ Harold S. Powers, "Dorian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ^ Harold S. Powers and Frans Wiering, "Mixolydian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell, 16:766–767 (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001), 767. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Harold S. Powers and Frans Wiering, "Hypomixolydian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 2nd edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell, 12:38 (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001) ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Dan Haerle, Scales for Jazz Improvisation (Hialeah: Columbia Pictures Publications; Lebanon, Indiana: Studio P/R; Miami: Warner Bros, 1983), p. 15. ISBN 978-0-89898-705-8.

- ^ Berle, Arnie (1 April 1997). "The Mixolydian Mode/Dominant Seventh Scale". Mel Bay's Encyclopedia of Scales, Modes and Melodic Patterns: A Unique Approach to Developing Ear, Mind and Finger Coordination. Mel Bay Publications, Incorporated. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7866-1791-3.

- ^ a b Serena, Desi (2021). Guitar Theory For Dummies with Online PracticeM, p.168. Wiley. ISBN 9781119843177.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (2008). Stuff! Good Piano Players Should Know, p. 78. Hal Leonard. ISBN 9781423427810.

- ^ Dick Weissman and Dan Fox, A Guide to Non-Jazz Improvisation: Guitar Edition (Pacific, Missouri: Mel Bay Publications, 2009): p. 130. ISBN 978-0-7866-0751-8.

- ^ a b Kachulis, Jimmy (2004). The Songwriter's Workshop, p.39. Berklee Press. ISBN 9781476867373

- ^ Serna, Desi (2021). Guitar Theory For Dummies with Online Practice, p.272. ISBN 9781119842972

- ^ Wendy Anthony, "Building a Traditional Tune Repertoire: Old Joe Clark (Key of A-Mixolydian) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", Mandolin Sessions webzine (February 2007) |(Accessed 2 February 2010).

- ^ Ted Eschliman, "Something Old. Something New Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", Mandolin Sessions webzine (November 2009) (Accessed 2 February 2010).

- ^ Micheal Houlahan, Philip Tacka (2015). Kodály in the Fifth Grade Classroom, p.104. Oxford. ISBN 9780190236243.

- ^ Houlahan, Michael and Tacka, Philip (2008). Kodaly Today, p.56. Oxford. ISBN 9780198042860.

- ^ "Paddy's Green Shamrock Shore" – via thesession.org.

- ^ "Paddy's Green Shamrock Shore - Download Sheet Music PDF file".

- ^ Allen, Patrick (1999). Developing Singing Matters. Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 0-435-81018-9. OCLC 42040205. [dead link]

- ^ a b Walter Piston. Harmony (New York: W. W. Norton, 1941): pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Farrant, Dan (24 October 2021). "12 Examples Of Songs In The Mixolydian Mode". Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Concerto in Modo Misolidio for Piano and Orchestra – Three Preludes on Gregorian Themes" by Adriano, English adaptation by David Nelson, Naxos Records cat. 8.220176 (1986)

- ^ "Sweet Child O' Mine by Guns N' Roses Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis - Hooktheory". www.hooktheory.com. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Thunderstruck by AC DC Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis - Hooktheory". www.hooktheory.com. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Leonard Bernstein on Rock Music" – via YouTube.

- ^ "The Mixolydian Mode--The Sound of Rock" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Express Yourself by Madonna Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis". HookTheory.com. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "The Mixolydian Mode--The Sound of Rock (at 1:46)" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Getting Really Medieval?: Mixolydian Mode in Lorde's "Royals"".

- ^ "Born This Way by Lady Gaga Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis". HookTheory.com. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Why 'Single Ladies' is so cool | Q+A" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Shake It Off by Taylor Swift Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis - Hooktheory". hooktheory.com.

- ^ "Changing the Mix: Mixolydian Mode in Coldplay's "Clocks"". Rebel Music Teacher.

- ^ a b c d e f "7 songs featuring Mixolydian mode". Music Tales. 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Happy Together by The Turtles Chords, Melody, and Music Theory Analysis - Hooktheory". hooktheory.com.

- ^ a b Gross, David (1997). Harmonic Colours in Bass, p.28. ISBN 9781576239353.

- ^ "Who is the original singer of the Revelation Song". steadyprintshop.com.

- ^ "Revelation Song | Official Song Resources on SongSelect®". songselect.ccli.com.

Further reading[edit]

- Hewitt, Michael. Musical Scales of the World. The Note Tree. 2013. ISBN 978-0957547001.

External links[edit]

Media related to Mixolydian mode at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mixolydian mode at Wikimedia Commons- Mixolydian scale on guitar