New Left

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

|

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer lifestyles on a broad range of social issues such as feminism, gay rights, drug policy reforms, and gender relations.[1] The New Left differs from the traditional left in that it tended to acknowledge the struggle for various forms of social justice, whereas previous movements prioritized explicitly economic goals. However, many have used the term "New Left" to describe an evolution, continuation, and revitalization of traditional leftist goals.[2][3][4]

Some who self-identified as "New Left"[5] rejected involvement with the labor movement and Marxism's historical theory of class struggle,[6] although others gravitated to their own takes on established forms of Marxism, such as the New Communist movement (which drew from Maoism) in the United States or the K-Gruppen[a] in the German-speaking world. In the United States, the movement was associated with the anti-war college-campus protest movements, including the Free Speech Movement.

Background

[edit]

The origins of the New Left have been traced to several factors. Prominently, the confused response of the Communist Party of the USA and the Communist Party of Great Britain to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 led some Marxist intellectuals to develop a more democratic approach to politics, opposed to what they saw as the centralised and authoritarian politics of the pre-war leftist parties. Those Communists who became disillusioned with the Communist Parties due to their authoritarian character eventually formed the "new left", first among dissenting Communist Party intellectuals and campus groups in the United Kingdom, and later alongside campus radicalism in the United States and in the Western Bloc.[8] The term nouvelle gauche was already current in France in the 1950s. It was associated with France Observateur, and its editor Claude Bourdet, who attempted to form a third position, between the dominant Stalinist and social democratic tendencies of the left, and the two Cold War blocs. It was from this French "new left" that the "First New Left" of Britain borrowed the term.[9]

The German critical theorist Herbert Marcuse is referred to as the "Father of the New Left". He rejected an orthodox Marxist view of the revolutionary proletariat; instead, Marcuse considered the student movements and the Black Power movement as the new opposition to capitalism. In a speech to the University of California, Berkeley in 1971, Marcuse said: "I still consider the radical student movement and the Black and Brown militants as the only real opposition we have in this country."[10] According to Leszek Kołakowski, noted critic of Marxist thought, Marcuse argued that since "all questions of material existence have been solved, moral commands and prohibitions are no longer relevant". He regarded the realization of man's erotic nature, or Eros, as the true liberation of humanity, which inspired the utopias of Jerry Rubin and others.[11] However, Marcuse also believed the concept of Logos, which involves one's reason, would absorb Eros over time as well.[12] Prominent New Left thinker Ernst Bloch believed that socialism would prove the means for all human beings to become immortal and eventually create God.[13]

The writings of sociologist C. Wright Mills, who popularized the term 'New Left' in a 1960 open letter,[14] would also give great inspiration to the movement. Mills' biographer, Daniel Geary, writes that his writings had a "particularly significant impact on New Left social movements of the 1960s".[15]

Origins in the United Kingdom

[edit]As a result of Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech denouncing Joseph Stalin, many abandoned the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and began to rethink its orthodox Marxism. Some joined various Trotskyist groupings or the Labour Party.[16]

The Marxist historians E. P. Thompson and John Saville of the Communist Party Historians Group published a dissenting journal within the CPGB called Reasoner. Refusing to discontinue the publication at the behest of the CPGB, the two were suspended from party membership and relaunched the journal as The New Reasoner in the summer of 1957.

Thompson was especially important in bringing the concept of a "New Left" to the United Kingdom in the summer of 1959 with a New Reasoner lead essay, in which he described

a generation which never looked upon the Soviet Union as a weak but heroic Workers' State; but rather as the nation of the Great Purges and Stalingrad, of Stalin's Byzantine Birthday and of Khrushchev's Secret Speech; as the vast military and industrial power which repressed the Hungarian rising and threw the first sputniks into space....

A generation nourished on 1984 and Animal Farm, which enters politics at the extreme point of disillusion where the middle-aged begin to get out. The young people... are enthusiastic enough. But their enthusiasm is not for the Party, or the Movement, or the established Political Leaders. They do not mean to give their enthusiasm cheaply away to any routine machine. They expect the politicians to do their best to trick or betray them. ... They prefer the amateur organisation and amateurish platforms of the Nuclear Disarmament Campaign to the method and manner of the left wing professional. ... They judge with the critical eyes of the first generation of the Nuclear Age.[17]

Later that year, Saville published a piece in the same journal which identified the emergence of the British New Left as a response to the increasing political irrelevance of socialists inside and outside the Labour Party during the 1950s, which he saw as being the result of a failure by the established left to come to grips with the political changes that had come to pass internationally after World War II and with the post–World War II economic expansion and the socio-economic legacy of the Attlee ministry:

The most important single reason for the miserable performance of the Left in this past decade is the simple fact of its intellectual collapse in the face of full employment and the welfare state at home, and of a new world situation abroad. The Left in domestic matters has produced nothing of substance to offset the most important book of the decade – Crosland's "The Future of Socialism" – a brilliant restatement of Fabian ideas in contemporary terms. We have made no sustained critique of the economics of capitalism in the 1950s, and our vision of a socialist society has changed hardly at all since the days of Keir Hardie. Certainly a minority has begun to recognise our deficiencies in the most recent years, and there is no doubt that the seeds which have already been sown will bring an increasing harvest as we move along the sixties. But we still have a long way to go, and there are far too many timeless militants for whom the mixture is the same as before.[18]

In 1960, The New Reasoner merged with the Universities and Left Review to form the New Left Review. These journals attempted to synthesise a theoretical position of a Marxist revisionism, humanist, socialist Marxism, departing from orthodox Marxist theory. This publishing effort made the ideas of culturally oriented theorists available to an undergraduate reading audience.

In this early period, many on the New Left were involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), formed in 1957. According to Robin Blackburn, "The decline of CND by late 1961, however, deprived the New Left of much of its momentum as a movement, and uncertainties and divisions within the Board of the journal led to the transfer of the Review to a younger and less experienced group in 1962."[19]

Under the long-standing editorial leadership of Perry Anderson, the New Left Review popularised the Frankfurt School, Antonio Gramsci, Louis Althusser, and other forms of Marxism.[19] Other periodicals like Socialist Register, started in 1964, and Radical Philosophy, started in 1972, have also been associated with the New Left, and published a range of important writings in this field.

As the campus orientation of the American New Left became clear in the mid to late 1960s, the student sections of the British New Left began taking action. The London School of Economics became a key site of British student militancy.[20] The influence of protests against the Vietnam War and of the May 1968 events in France were also felt strongly throughout the British New Left. Some within the British New Left joined the International Socialists, which later became Socialist Workers Party, while others became involved with groups such as the International Marxist Group.[21] The politics of the British New Left can be contrasted with Solidarity, which continued to focus primarily on industrial issues.[22]

Another significant figure in the British New Left was Stuart Hall, a black cultural theorist in Britain. He was the founding editor of the New Left Review in 1960.

The New Left Review, in an obituary following Hall's death in February 2014, wrote: "His exemplary investigations came close to inventing a new field of study, 'cultural studies'; in his vision, the new discipline was profoundly political in inspiration and radically interdisciplinary in character."[23]

Numerous Black British scholars attributed their interest in cultural studies to Hall, including Paul Gilroy, Angela McRobbie, Isaac Julien, and John Akomfrah. In the words of Indian literary theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Academics worldwide could not think 'Black Britain' before Stuart Hall. And in Britain the impact of Cultural Studies went beyond the confines of the academy."[24]

Development in United States

[edit]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

In the United States, the "New Left" was the name loosely associated with radical, Marxist political movements that took place during the 1960s, primarily among college students. At the core of this was the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).[25] Noting the perversion of "the older Left" by "Stalinism", in their 1962 Port Huron Statement the SDS eschewed "formulas" and "closed theories". Instead they called for a "new left ... committed to deliberativeness, honesty [and] reflection".[26] The New Left that developed in the years that followed was "a loosely organized, mostly white student movement that advocated for democracy, civil rights, and various types of university reforms, and protested against the Vietnam war".[27]

The term "New Left" was popularised in the United States in an open letter written in 1960 by sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916–1962) entitled Letter to the New Left.[28] Mills argued for a new leftist ideology, moving away from the traditional ("Old Left") focus on labor issues (whose entrenched leadership in the U.S. supported the Cold War and pragmatic establishment politics), into a broader focus towards issues such as opposing alienation, anomie, and authoritarianism. Mills argued for a shift from traditional leftism, toward the values of the counterculture, and emphasized an international perspective on the movement.[29] According to David Burner, C. Wright Mills claimed that the proletariat (collectively the working-class referencing Marxism) were no longer the revolutionary force; the new agents of revolutionary change were young intellectuals around the world.[30]

A student protest called the Free Speech Movement took place during the 1964–1965 academic year on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley under the informal leadership of students Mario Savio, Jack Weinberg, Brian Turner, Bettina Aptheker, Steve Weissman, Art Goldberg, Jackie Goldberg, and others. In protests unprecedented in this scope at the time, students insisted that the university administration lift the ban of on-campus political activities and acknowledge the students' right to free speech and academic freedom. In particular, on 2 December 1964 on the steps of Sproul Hall, Mario Savio gave a famous speech: "But we're a bunch of raw materials that don't mean to be—have any process upon us. Don't mean to be made into any product! Don't mean—Don't mean to end up being bought by some clients of the University, be they the government, be they industry, be they organized labor, be they anyone! We're human beings! ... There's a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious—makes you so sick at heart—that you can't take part. You can't even passively take part. And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop. And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all."[31]

The New Left opposed what it saw as the prevailing authority structures in society, which it termed "The Establishment", and those who rejected this authority became known as "anti-Establishment". The New Left focused on social activists and their approach to organization, convinced that they could be the source for a better kind of social revolution.

The New Left in the United States also included anarchist, countercultural, and hippie-related radical groups such as the Yippies (who were led by Abbie Hoffman), the Diggers,[32] Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers, and the White Panther Party. By late 1966, the Diggers opened free stores which simply gave away their stock, provided free food, distributed free drugs, gave away money, organized free music concerts, and performed works of political art.[33] The Diggers took their name from the original English Diggers led by Gerrard Winstanley[34] and sought to create a mini-society free of money and capitalism.[35] On the other hand, the Yippies (the name allegedly coming from Youth International Party) employed theatrical gestures, such as advancing a pig ("Pigasus the Immortal") as a candidate for president in 1968, to mock the social status quo.[36] They have been described as a highly theatrical, anti-authoritarian, and anarchist[37] youth movement of "symbolic politics".[38] According to ABC News, "The group was known for street theater pranks and was once referred to as the 'Groucho Marxists'."[39] Many of the "old school" political left either ignored or denounced them.

Many New Left thinkers in the United States were influenced by the Vietnam War and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Some in the U.S. New Left argued that since the Soviet Union could no longer be considered the world center for proletarian revolution, new revolutionary Communist thinkers had to be substituted in its place, such as Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro.[40] Todd Gitlin in The Whole World Is Watching in describing the movement's influences stated, "The New Left, again, refused the self-discipline of explicit programmatic statement until too late—until, that is, the Marxist–Leninist sects filled the vacuum with dogmas, with clarity on the cheap."[41]

Isserman (2001) reports that the New Left "came to use the word 'liberal' as a political epithet".[42] Historian Richard Ellis (1998) says that the SDS's search for their own identity "increasingly meant rejecting, even demonizing, liberalism".[43] As Wolfe (2010) notes, "no one hated liberals more than leftists".[44]

Other elements of the U.S. New Left were anarchist and looked to libertarian socialist traditions of American radicalism, the Industrial Workers of the World and union militancy. This group coalesced around the historical journal Radical America. American Autonomist Marxism was also a child of this stream, for instance in the thought of Harry Cleaver. Murray Bookchin was also part of the anarchist stream of the New Left, as were the Yippies.[45]

The U.S. New Left drew inspiration first from the civil disobedience of the civil rights movement, particularly the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and then from black radicalism, particularly the Black Power movement and the more explicitly Maoist and militant Black Panther Party. The Panthers in turn influenced other similar militant groups, like the Young Lords, the Brown Berets and the American Indian Movement. Students immersed themselves into poor communities building up support with the locals.[46] The New Left sought to be a broad based, grass roots movement.[47]

The Vietnam War conducted by liberal President Lyndon B. Johnson was a special target across the worldwide New Left. Johnson and his top officials became unwelcome on American campuses. The anti-war movement escalated the rhetorical heat, as violence broke out on both sides. The climax came at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

The New Left also accommodated the rebirth of feminism.[48] With sexism being rampant in various fractions of the New Left,[49][50] women reacted to the lack of progressive gender politics with their own social intellectual movement.[51] The New Left was also marked by the invention of the modern environmentalist movement, which clashed with the Old Left's disregard for the environment in favor of preserving the jobs of union workers. Environmentalism also gave rise to various other social justice movements such as the environmental justice movement, which aims to prevent the toxification of the environment of minority and disadvantaged communities.[2]

By 1968, however, the New Left coalition began to split. The anti-war Democratic presidential nomination campaign of Kennedy and McCarthy brought the central issue of the New Left into the mainstream liberal establishment. The 1972 nomination of George McGovern further highlighted the new influence of Liberal protest movements within the Democratic establishment. Increasingly, feminist and gay rights groups became important parts of the Democratic coalition, thus satisfying many of the same constituencies that were previously unserved by the mainstream parties.[1] This institutionalization took away all but the most radical members of the New Left. The remaining radical core of the SDS, dissatisfied with the pace of change, incorporated violent tendencies towards social transformation. After 1969, the Weathermen, a surviving faction of SDS, attempted to launch a guerrilla war in an incident known as the "Days of Rage". Finally, in 1970 three members of the Weathermen blew themselves up in a Greenwich Village brownstone trying to make a bomb out of a stick of dynamite and an alarm clock.[52] Port Huron Statement participant Jack Newfield wrote in 1971 that "in its Weathermen, Panther and Yippee incarnations, [the New Left] seems anti-democratic, terroristic, dogmatic, stoned on rhetoric and badly disconnected from everyday reality".[53] In contrast, the more moderate groups associated with the New Left increasingly became central players in the Democratic Party and thus in mainstream American politics.

Hippies and Yippies

[edit]

The hippie subculture was originally a youth movement that arose in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to other countries around the world. The Beats adopted the term hip, and early hippies inherited the language and countercultural values of the Beat Generation and mimicked some of the current values of the British Mod scene. Hippies created their own communities, listened to psychedelic rock, embraced the sexual revolution, and some used drugs such as cannabis, LSD, and psilocybin mushrooms to explore altered states of consciousness.

The Yippies, who were seen as an offshoot of the hippie movements parodying as a political party, came to national attention during their celebration of the 1968 spring equinox, when some 3,000 of them took over Grand Central Terminal in New York, resulting in 61 arrests. The Yippies, especially their leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, became notorious for their theatrics, such as trying to levitate the Pentagon at the October 1967 war protest, and such slogans as "Rise up and abandon the creeping meatball!" Their stated intention to protest the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August, including nominating their own candidate, "Lyndon Pigasus Pig" (an actual pig), was also widely publicized in the media at this time.[54] In Cambridge, hippies congregated each Sunday for a large "be-in" at Cambridge Park with swarms of drummers and those beginning the Women's Movement. In the United States the hippie movement started to be seen as part of the "New Left" which was associated with anti-war college campus protest movements.[1]

Students for a Democratic Society

[edit]The organization that really came to symbolize the core of the New Left in the United States was the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). By 1962, the SDS had emerged as the most important of the new campus radical groups; soon it would be regarded as virtually synonymous with the "New Left".[55] In 1962, Tom Hayden wrote its founding document, the Port Huron Statement,[56] which issued a call for "participatory democracy" based on non-violent civil disobedience. This was the idea that individual citizens could help make "those social decisions determining the quality and direction" of their lives.[46] The SDS marshaled antiwar, pro-civil rights and free speech concerns on campuses, and brought together liberals and more revolutionary leftists.

The SDS became the leading organization of the anti-war movement on college campuses during the Vietnam War. As the war escalated the membership of the SDS also increased greatly as more people were willing to scrutinise political decisions in moral terms.[57]: 170 During the course of the war, the people became increasingly militant. As opposition to the war grew stronger, the SDS became a nationally prominent political organization, with opposing the war an overriding concern that overshadowed many of the original issues that had inspired SDS. In 1967, the old statement in Port Huron was abandoned for a new call for action,[57]: 172 which would inevitably lead to the destruction of the SDS.

In 1968 and 1969, as its radicalism reached a fever pitch, the SDS began to split under the strain of internal dissension and increasing turn towards Maoism.[58] Along with adherents known as the New Communist Movement, some extremist illegal factions also emerged, such as the Weather Underground organization.

The SDS suffered the difficulty of wanting to change the world while "freeing life in the here and now". This caused confusion between short-term and long-term goals. The sudden growth due to the successful rallies against the Vietnam War meant there were more people wanting action to end the Vietnam War, whereas the original New Left had wanted to focus on critical reflection.[59] In the end, it was the anti-war sentiment that dominated the SDS.[57]: 183

The New Storefront Left

[edit]Stung by the criticism that they were "high on analysis, low on action", and in "the year of the 'discovery of poverty'" (in 1963 Michael Harrington's book The Other America[60] "was the rage"), the SDS launched the Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP).[61] Conceived by Tom Hayden as forestalling "white backlash", community-organizing initiatives would unite Black, Brown, and White workers around a common program for economic change. The leadership commitment was sustained barely two years. With no early sign in the neighborhoods of an interracial movement that would "collectivize economic decision making and democratize and decentralize every economic, political, and social institution in America", many SDS organizers were readily induced by the escalating U.S. commitment in Vietnam to abandon their storefront offices, and heed the anti-war call to return to campus.[62]

In some of ERAP projects, such as the JOIN ("Jobs or Income Now") project in uptown Chicago, SDSers were replaced by white working-class activists (some bitterly conscious that their poor backgrounds had limited their acceptance within "the Movement"). In community unions such JOIN and its successors in Chicago, the Young Patriots and Rising Up Angry, White Lightening in the Bronx, and the 4 October Organization in Philadelphia white radicals (open in the debt they believed they owed to the SNCC and to the Black Panthers) continued to organise rent strikes, health and legal clinics, housing occupations and street protests against police brutality.[63]

While city-hall and police harassment was a factor, internal tensions ensured that these radical community-organizing efforts did not long survive the sixties.[64] Kirkpatrick Sale recalls that the most dispiriting feature of the ERAP experience was that, however much they might talk at night about "transforming the system", "building alternative institutions", and "revolutionary potential", the organizers knew that their credibility on the doorstep rested on an ability to secure concessions from, and thus to develop relations with, the local power structures. Far from erecting parallel structures, projects were built "around all the shoddy instruments of the state". ERAPers were caught in "a politics of adjustment".[65]

Development in Europe

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Frankfurt School |

|---|

|

The European New Left appeared first in West Germany and West Berlin, which became a prototype for European student radicals.[66] West Berlin, an Allied-occupied island within socialist East Germany to which young men from both German states had moved to avoid conscription, in particular became a center of critical dissent from the rival social-democratic and communist party traditions. At the beginning of the 1960, an early grouping was Subversive Action (Subversiven Aktion), conceived as the German branch of the Situationist International.[67] Associated with the charismatic East German emigre, and student of the Frankfurt School, Rudi Dutschke, it became a leasing faction within the German Socialist Students' Union (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund, SDS).[68]

Dutschke and his faction had an important ally in Michael Vester, SDS vice-president and international secretary. Vester, who had studied in the US in 1961–62, and worked extensively with the American SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), introduced the theories of the American New Left and supported the call for "direct action" and civil disobedience.[69] The theory as expounded by Dutschke in relation to protests against the Vietnam War, which soon dominated the agenda, was that "systematic, limited and controlled confrontations with the power structure" would "force the representative 'democracy' to show openly its class character, its authoritarianism, ... to expose itself as a 'dictatorship of force'". The awareness produced by such provocations would free people to rethink democratic theory and practice.[70][71] Dutschke was also influenced by Provo, a Dutch counterculture movement in the mid-1960s that focused on provoking violent responses from authorities using non-violent bait.

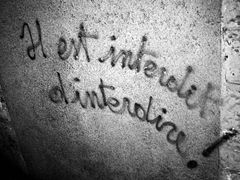

In France the Situationist International reached the apex of its creative output and influence in 1967 and 1968, with the former marking the publication of the two most significant texts of the situationist movement, The Society of the Spectacle by Guy Debord and The Revolution of Everyday Life by Raoul Vaneigem. The expressed writing and political theory of these texts, along with other situationist publications, proved greatly influential in shaping the ideas behind the May 1968 student and worker strikes and demonstrations in France; quotes, phrases, and slogans from situationist texts and publications were ubiquitous on posters and graffiti throughout France during the unrest.[72]

Another West Berlin manifestation of a new left was Kommune 1 or K1, the first politically motivated commune in Germany. It was created on 12 January 1967, in West Berlin and finally dissolved in November 1969. During its entire existence, Kommune 1 was infamous for its bizarre staged events that fluctuated between satire and provocation. These events served as inspiration for the "Sponti" movement and other leftist groups. In the late summer of 1968, the commune moved into a deserted factory on Stephanstraße in order to reorient. This second phase of Kommune 1 was characterized by sex, music, and drugs. All of a sudden, the commune was receiving visitors from all over the world, among them Jimi Hendrix, who turned up one morning in the bedroom of Kommune 1.[73]

The student activism of the New Left came to a head around the world in 1968. The May 1968 protests in France temporarily shut down the city of Paris, while the German student movement did the same in Bonn. Universities were simultaneously occupied in May in Paris, in the Columbia University protests of 1968, and in Japanese student strikes. Shortly thereafter, Swedish students occupied a building at Stockholm University. However, all of these protests were shut down by police authorities without achieving their goals, which caused the influence of the student movement to lapse in the 1970s.

Global overview

[edit]Australia

[edit]In Australia, the New Left was engaged in debates concerning the legitimacy of heterodox economics and political economy in tertiary education.[74] This culminated in the establishment of an independent department of political economy at the University of Sydney.[75][76]

Brazil

[edit]The Workers' Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores – PT) is considered the main organization to emerge from the New Left in Brazil. According to Manuel Larrabure, "rather than taking the path of the old Latin American left, in the form of the guerrilla movement, or the Stalinist party", PT decided to try something new, while being aided by CUT and other social movements. Its challenge was to "combine the institutions of liberal democracy with popular participation by communities and movements". However, PT has been criticized for its "strategic alliances" with the right wing after Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected president of Brazil. The party has distanced itself from social movements and youth organizations and for many it seems the PT's model of a new left is reaching its limits.[77]

China

[edit]The concept of New Left in China originates from the academic debate between "New Left" and "liberal" in the 1990s, both of which are common ideological labels in the Chinese mainland context.[78] In this context, the term "New Left" is often used to describe a faction that focuses on the continued widening of the urban-rural gap in the post-Deng Xiaoping era and calls for a critical re-evaluation of the legacy of the Mao era (including the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution) in response to the current situation.[79] The so-called Chinese New Left differs greatly from the Western New Left and is difficult to define clearly.[79] Under the one-party dictatorship, no "faction" in China can make political waves, so some scholars doubt the existence of a genuine New Left in China.[80]

Japan

[edit]

The New Left in Japan began by occupying college campuses for several years in the 1960s, culminating in the 1968–69 Japanese university protests. After 1970, they splintered into several freedom fighter groups including the United Red Army and the Japanese Red Army. They also developed the political ideology of Anti-Japaneseism.

Latin America

[edit]The New Left in Latin America can be loosely defined as the collection of political parties, radical grassroots social movements (such as indigenous movements, student movements, mobilizations of landless rural workers, afro-descendent organizations and feminist movements), guerilla organizations (such as the Cuban and Nicaraguan revolutions) and other organizations (such as trade unions, campesino leagues and human rights organizations) that comprised the left between 1959 (with the beginning of the Cuban Revolution) and 1990 (with the fall of the Berlin Wall).[81]

Influential Latin American thinkers such as Francisco de Oliveira argued that the United States used Latin American countries as "peripheral economies" at the expense of Latin American society and economic development, which many saw as an extension of neo-colonialism and neo-imperialism.[82]

The New Left in Latin America sought to go beyond existing Marxist–Leninist efforts at achieving economic equality and democracy to include social reform and address issues unique to Latin America such as racial and ethnic equality, indigenous rights, the rights of the environment, demands for radical democracy, international solidarity, anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism and other aims.[81]

Organizations

[edit]France

[edit]Germany

[edit]- Außerparlamentarische Opposition

- Red Army Faction

- Revolutionary Cells (German group)

- Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (from 1967)

Italy

[edit]Japan

[edit]Soviet Union

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]United States

[edit]- American Indian Movement

- Antonio Maceo Brigade

- Black Panther Party

- Black Liberation Army

- Brown Berets

- Diggers

- New American Movement

- Red Guard Party

- Students for a Democratic Society

- Symbionese Liberation Army

- Up Against the Wall Motherfucker

- White Panther Party

- Young Lords

- Young Patriots Organization

- Youth International Party

See also

[edit]- American Left

- Anarcho-communism

- British Left

- Congress for Cultural Freedom

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Drug policy reform

- Environmental movement

- Feminist movement

- Green left

- Left-libertarianism

- LGBT history

- LGBT movements

- Marxist cultural analysis

- Neoliberalism

- Neoconservatism

- New Right

- Old Left

- Reformist Left

- Regressive left

- Revisionism (Marxism)

- Shinjwapa

- Structural Marxism

- Third World socialism

- Timeline of history of environmentalism

- Woke

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The K-Gruppen originally referred to the mainly Maoist-oriented small parties and other associations that had emerged in the 1960s with the disintegration of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS) and the associated decline of the West German student movement. The term "K group" has been used primarily by competing left groups as well as in the media. It served as a collective name for the numerous, often violently divided groups and alluded to their common self-image as communist cadre organizations. The German term Kader denotes the civil servants or party functionaries in autocratic state systems, especially in socialist states (today, among others, the People's Republic of China and Cuba). In the Soviet sphere of influence, cadres were a group of people in the party and ideology sector with political and technical knowledge and skills ("party cadres", "leadership cadres", "leadership cadres", "junior cadres", "cadre policy", "cadre management"). In particular, they included the functionaries of the parties and mass organizations (executives), and university and technical college graduates (experts), but not normal working people. The personnel department of a company was called "Kaderabteilung" in the GDR; the head of this department was called "Kaderleiter".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Carmines, Edward G.; Layman, Geoffrey C. (1997). "Issue Evolution in Postwar American Politics". In Shafer, Byron (ed.). Present Discontents. NJ: Chatham House Publishers. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-56643-050-0.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Cynthia (2003). Ideas for Action: Relevant Theory for Radical Change. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-693-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (2001). "The Left's Lost Universalism". In Melzer, Arthur M.; Weinberger, Jerry; Zinman, M. Richard (eds.). Politics at the Turn of the Century. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 3–26.

- ^ Farred, Grant (2000). "Endgame Identity? Mapping the New Left Roots of Identity Politics". New Literary History. 31 (4): 627–48. doi:10.1353/nlh.2000.0045. JSTOR 20057628. S2CID 144650061.

- ^ Thompson, Willie (1996). The Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century Politics. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-74530891-3.

- ^ Coker, Jeffrey W. (2002). Confronting American Labor: The New Left Dilemma. University of Missouri Press.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas. "Herbert Marcuse". University of Texas.

- ^ Kenny, Michael. The First New Left: British Intellectuals After Stalin. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- ^ Hall, Stuart (January–February 2010). "Life and times of the first New Left". New Left Review. II (61). New Left Review.

- ^ Herbert, Marcuse (2017). Kellner, Douglas (ed.). Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse: The New Left and the 60s. Routledge. p. 142.

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek (1981). Main Currents Of Marxism. Vol. III. Oxford University Press. p. 416. ISBN 0-19-285109-8.

- ^ Marcuse, Herbert (1955). Eros and Civilization. Beacon Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1-135-86371-5. Retrieved 28 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Kołakowski, Leszek (1981). Main Currents Of Marxism. Vol. III. Oxford University Press. pp. 436–440. ISBN 0-19-285109-8, quoting Dans Prinzip Hoffnung pp. 1380–1628.

- ^ Wright, C. Wright (1960). Letter to the New Left – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Geary, Daniel (2009). Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought. University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780520943445 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dworkin, Dennis L. (1997). Cultural Marxism in postwar Britain: history, the new left, and the origins of cultural studies. p. 46.

- ^ Thompson, E. P. (Summer 1959). "The New Left". The New Reasoner. No. 9. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Saville, John (Autumn 1959). "A Note on West Fife" (PDF). New Reasoner (10): 9–13. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ a b Blackburn, Robin. "A brief history of New Left Review". New Left Review.

Anderson took over as editor in 1962.

- ^ Hoch and Schoenbach, 1969

- ^ Adams, Ian (1998). Ideology and politics in Britain today. p. 191.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (2005). Street-Fighting Years: An Autobiography of the Sixties.

- ^ Blackburn, Robin (March–April 2014). "Stuart Hall: 1932–2014". New Left Review. II (86). New Left Review.

- ^ Chakravorty Spivak, Gayatri (1 May 2014). "Stuart Hall, 1932–2014". Radical Philosophy. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 151.

- ^ Students for a Democratic Society (1962). The Port Huron Statement. Port Huron, Michigan. OCLC 647506237.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ McMillian, John; Buhle, Paul, eds. (2003). The New Left Revisited. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 5.

- ^ Wright Mills, C. (1960). "Letter to the New Left". New Left Review (5) – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Geary, Daniel (December 2008). "'Becoming International Again': C. Wright Mills and the Emergence of a Global New Left, 1956–1962". Journal of American History. 95 (3): 710–736. doi:10.2307/27694377. JSTOR 27694377.

- ^ Burner 1996, p. 155.

- ^ Eidenmuller, Michael E. "American Rhetoric: Mario Savio – Sproul Hall Sit-In Address". American Rhetoric. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ McMillian, John Campbell; Buhle, Paul (2003). The new left revisited. Temple University Press. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-1-56639-976-0. Retrieved 28 December 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lytle, Mark H. (2006). America's Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon. Oxford University Press. pp. 213, 215. ISBN 0-19-517496-8.

- ^ "Overview: who were (are) the Diggers?". The Digger Archives. Retrieved 17 June 2007.

- ^ Gail Dolgin; Vicente Franco (2007). American Experience: The Summer of Love. PBS. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ Holloway, David (2002). "Yippies". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture.

- ^ Hoffman, Abbie (1980). Soon to be a Major Motion Picture. Perigee Books. p. 128.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (1993). The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York. p. 286. ISBN 9780553372120.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "1969: Height of the Hippies". ABC News. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Bacciocco, Edward J. (1974). The New Left in America: reform to revolution, 1956 to 1970. p. 21.

- ^ Gitlin, Todd (2003). The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. University of California Press. p. 179.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice (2001). The other American: the life of Michael Harrington. p. 276.

- ^ Ellis, Richard J. (1998). The dark side of the Left: illiberal Egalitarianism in America. p. 129.

- ^ Wolfe, Alan (13 May 2010). "Jeremiah, American-style". New Republic. p. 31.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (2005). Anarchist voices: an oral history of anarchism in America. p. 527.

- ^ a b Isserman, Maurice; Kazin, Michael (2000). America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 169.

- ^ McMillian, John; Buhle, Paul, eds. (2003). The New Left Revisited. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 4.

- ^ Isserman, Maurice; Kazin, Michael (2000). America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 295.

- ^ Breines, Winifred (2006). The Trouble between Us: An Uneasy History of White and Black Women in the Feminist Movement. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195179040.003.0003. ISBN 9780199788583.

- ^ Esensten, Andrew (19 July 2022). "'Yippie Girl': Judy Gumbo's memoir of 'defeating the FBI'". J. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ McMillian, John; Buhle, Paul, eds. (2003). The New Left Revisited. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 6.

- ^ "America in Ferment: The Tumultuous 1960s". Digital History. University of Houston. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011.

- ^ Newfield, Jack (19 July 1971). "A Populist Manifesto: The Making of a New Majority". New York. pp. 39–46. Retrieved 6 January 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Politics of Yip". Time. 5 April 1968.

- ^ Maurice Isserman, If I Had a Hammer: The Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left (New York: Basic Books, 1987) 174.

- ^ "Port Huron Statement of the Students for a Democratic Society, 1962". Coursesa.matrix.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Maurice Isserman & Michael Kazin, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- ^ McCormick, Richard (2014). Politics of the Self: Feminism and the Postmodern in West German Literature and Film. Princeton University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4008-6164-4.

In 1969, the American organization ruptured into two factions, one Maoist and one proterrorist.

- ^ McMillian, John; Buhle, Paul, eds. (2003). The New Left Revisited. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Michael Harrington, The Other America, Macmillan, 1962

- ^ Richard Rothstein, A Short History of ERAP

- ^ Manfred McDowell (2013), "A Step into America: The New Left Organizes the Neighborhood", New Politics Vol. XIV No. 2, pp. 133–141

- ^ Amy Sony, James Tracy (2011), Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times. Brooklyn, Melville House

- ^ McDowell

- ^ Kirkpatrick Sale (1973), SDS: The Rise and Development of The Students for a Democratic Society. Random House

- ^ Stanley Rothman and S. Robert Lichter, Roots of radicalism: Jews, Christians, and the Left (1996) p. 354

- ^ Klimke, Martin; Scharloth, Joachim (2009). "Utopia in Practice: The Discovery of Performativity in Sixties' Protest, Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Historein. 9: 4–6.

- ^ "Rudi Dutschke and the German student movement in 1968". Socialist Worker (Britain). 29 April 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Hilwig, Stuart (2011). Klimke, Martin (ed.). "The SDS, a Transatlantic Alliance, Red and Black Panthers". Diplomatic History. 35 (5): 933–936. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2011.01002.x. ISSN 0145-2096. JSTOR 44254548.

- ^ Merritt (1969), p. 521

- ^ Kraushaar, Wolfgang (20 August 2007). "Rudi Dutschke und der bewaffnete Kampf". bpb (in German). Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Plant, Sadie (1992). The Most Radical Gesture. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06222-0.

- ^ Victor Bockris,Keith Richards: The Biography

- ^ G Butler, E. Jones, F. J. B. Stilwell (2009). Political economy now!: The struggle for alternative economics at the University of Sydney. Darlington Press

- ^ Williams-Brooks, Llewellyn (2016). "Radical Theories of Capitalism in Australia: Towards a Historiography of the Australian New Left". Honours thesis, University of Sydney, Retrieved 20 April 2017, hdl:2123/16655

- ^ Political economy University of Sydney Retrieved 3 May 2017

- ^ Larrabure, Manuel. "'Não nos representam!' A left beyond the Workers Party?". The Bullet. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ 萧功秦 (2002-01-01). "新左派与当代中国知识分子的思想分化".

- ^ a b Hioe, Brian (2016-03-03). "What is the Chinese New Left?: Between Leftism and Nationalism?". New Bloom.

- ^ "丁学良:中国只有老左派 没有新左派". 2010-08-27. Archived from the original on 2013-01-17.

- ^ a b Barrett, Patrick; Chavez, Daniel; Rodríguez-Garavito, César (2008). The New Latin American Left: Utopia Reborn. Pluto Press.

- ^ Cardoso, F. H.; Faletto, E. (1969). Dependency and development in Latin America. University of California Press.

Bibliography

[edit]- Burner, David (1996). Making Peace with the 60s. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Further reading

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Teodori, Massimo, ed., The New Left: A documentary History. London: Jonathan Cape (1970).

- Oglesby, Carl (ed.) The New Left Reader Grove Press (1969). ISBN 83-456-1536-8. Influential collection of texts by Mills, Marcuse, Fanon, Cohn-Bendit, Castro, Hall, Althusser, Kolakowski, Malcolm X, Gorz & others.

General

[edit]- Michael R. Krätke, Otto Bauer and the early "Third Way" to Socialism

- Detlev Albers u.a. (Hg.), Otto Bauer und der "dritte" Weg. Die Wiederentdeckung des Austromarxismus durch Linkssozialisten und Eurokommunisten, Frankfurt/M 1979

- Andrews, Geoff; Cockett, Richard; Hooper, Alan; Williams, Michael, New Left, New Right and Beyond. Taking the Sixties Seriously. Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. ISBN 9780333741474

Australia

[edit]- Armstrong, Mick, 1,2,3, What Are We Fighting For? The Australian Student Movement From Its Origins To The 1970s, Melbourne; Socialist Alternative, 2001. ISBN 0957952708

- Cahill, Rowan, Notes on the New Left in Australia, Sydney: Australian Marxist Research Foundation, 1969.

- Hyde, Michael (editor), It is Right to Rebel, Canberra: The Diplomat, 1972.

- Gordon, Richard (editor), The Australian New Left: Critical Essays and Strategy, Melbourne: Heinnemann Australia,1970. ISBN 0855610093

- Symons, Beverley and Rowan Cahill (editors), A Turbulent Decade: Social Protest Movements and the Labour Movement, 1965–1975, Newtown: Sydney ASSLH, 2005. ISBN 0909944091

- Williams-Brooks, Llewellyn, Radical Theories of Capitalism in Australia: Towards a Historiography of the Australian New Left, Honours Thesis, University of Sydney: Sydney, 2016, viewed 19 April 2017, hdl:2123/16655

Canada

[edit]- Anastakis, Dimitry, ed (2008). The sixties: Passion, politics, style (McGill Queens University Press).

- Cleveland, John. (2004) "New Left, not new liberal: 1960s movements in English Canada and Quebec", Canadian Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 41, no. 4: 67–84.

- Kostash, Myrna. (1980) Long way from home: The story of the sixties generation in Canada. Toronto: Lorimer.

- Levitt, Cyril. (1984). Children of privilege: Student revolt in the sixties. University of Toronto Press.

- Sangster, Joan. "Radical Ruptures: Feminism, Labor, and the Left in the Long Sixties in Canada", American Review of Canadian Studies, Spring 2010, Vol. 40 Issue 1, pp. 1–21

Germany

[edit]- Timothy Scott Brown. West Germany and the Global Sixties: The Anti-Authoritarian Revolt, 1962–1978. Cambridge University Press. 2013

Japan

[edit]- Miyazaki, Manabu (2005). Toppamono: Outlaw, Radical, Suspect: My Life in Japan's Underworld. Tōkyō: Kotan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9701716-2-7. Includes an account of the author's days as a student activist and street fighter for the Japanese Communist Party, 1964–1969.; A primary source

- Andrews, William Dissenting Japan: A History of Japanese Radicalism and Counterculture, from 1945 to Fukushima.. London: Hurst, 2016. ISBN 978-1849045797. Includes summaries of the student movement and various New Left groups in postwar Japan.

United Kingdom

[edit]- Ali, Tariq. Street Fighting Years: An Autobiography of the Sixties London: Collins, 1987. ISBN 0-00-217779-X; A primary source

- Hock, Paul and Vic Schoenbach. LSE: the natives are restless, a report on student power in action London: Sheed and Ward, 1969. ISBN 0-7220-0596-2.; A primary source

- The New Left's renewal of Marxism an account by Paul Blackledge from International Socialism

British New Left periodicals

[edit]- "The New Reasoner". indexed articles online. 1957–1959. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- "Marxism Today". indexed articles online. Communist Party of Great Britain and Marxism Today. 1980–1991. Retrieved 16 October 2006. (also 1998 special issue)

- "Indexed articles online". newleftreview.org. New Left Review. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- "Socialist Register". indexed articles online. 1964–1999. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- "Universities & Left Review". indexed articles online. 1957–1959. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

British New Left articles

[edit]- Mills, C. Wright (September–October 1960). "Letter to the New Left". New Left Review. I (5). New Left Review. Full text.

- "Placating Mr. Jenkins". Article discussing online archiving of four British New Left publications Universities & Left Review, Marxism Today, The New Reasoner and Socialist Register. 16 October 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

United States

[edit]- Bahr, Ehrhard (2008). Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25795-5.

- Breines, Wini. Community Organization in the New Left, 1962–1968: The Great Refusal, reissue edition (Rutgers University Press, 1989). ISBN 0-8135-1403-7.

- Cohen, Mitchell, and Hale, Dennis, eds. The New Student Left (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966).

- Elbaum, Max. Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals turn to Lenin, Che and Mao. (Verso, 2002).

- Evans, Sara. Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left (Vintage, 1980). ISBN 0-394-74228-1.

- Frost, Jennifer. "An Interracial Movement of the Poor": Community Organizing & the New Left in the 1960s (New York University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-8147-2697-6.

- Gosse, Van. The Movements of the New Left, 1950–1975: A Brief History with Documents (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2004). ISBN 0-312-13397-9.

- Isserman, Maurice. If I had a Hammer: the Death of the Old Left and the Birth of the New Left, reprint edition (University of Illinois Press, 1993). ISBN 0-252-06338-4.

- Klatch, Rebecca E. A Generation Divided: The New Left, the New Right, and the 1960s. (Berkeley : University of California Press, 1999). ISBN 0-520-21714-4.

- Long, Priscilla, ed. The New Left: A Collection of Essays (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1969).

- Mattson, Kevin, Intellectuals in Action: The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945–1970 (Penn State Press, 2002). ISBN 0-271-02206-X

- McMillian, John and Buhle, Paul (eds.). The New Left Revisited (Temple University Press, 2003). ISBN 1-56639-976-9.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick. SDS: The Rise and Development of The Students for a Democratic Society. (Random House, 1973).

- Novack, George; writing as "William F. Warde" (1961). "Who Will Change The World? The New left and the Views of C. Wright Mills". International Socialist Review. 22 (3). USFI: 67–79. Retrieved 16 October 2006.

- Rand, Ayn. The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution (New York: Penguin Books, 1993, 1975). ISBN 0-452-01125-6.

- Rossinow, Doug. The Politics of Authenticity: Liberalism, Christianity, and the New Left in America (Columbia University Press, 1998). ISBN 0-231-11057-X.

- Rubenstein, Richard E. Left Turn: Origins of the Next American Revolution (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973).

- Young, C. A. Culture, Radicalism, and the Making of a US Third World Left (Duke University Press, 2006).

Primary sources: US

[edit]- Albert, Judith Clavir, and Stewart Edward Albert (1984). The Sixties Papers: Documents of a Rebellious Decade. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-91781-9.

- Committee on Internal Security, Anatomy of a Revolutionary Movement, Students for a Democratic Society. Report by the committee on Internal Security. House of Representatives. Ninety-first Congress. Second Session. 6 October 1970. Washington: U.S. Government P.O.. 1970

- Jaffe, Harold, and John Tytell (eds.) (1970). The American Experience: A Radical Reader. New York: Harper & Row. xiii, 480 pp. OCLC 909407028.

Archives

[edit]- New Left Movement: 1964–1973. Archive # 88-020. Title: New Left Movement fonds. 1964–1973. 51 cm of textual records. Trent University Archives. Peterborough, Ontario, Canada. Online guide retrieved April 12, 2005.

- Russ Gilbert "New Left" Pamphlet Collection: An inventory of the collection at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Online guide retrieved October 8, 2005