Plasencia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (June 2014) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding articles in Portuguese and Spanish. (December 2021) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Plasencia | |

|---|---|

View of Plasencia | |

| Coordinates: 40°02′N 06°06′W / 40.033°N 6.100°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Extremadura |

| Province | Cáceres |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fernando Pizarro (PP) |

| Area | |

• Total | 218 km2 (84 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 415 m (1,362 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 40,141 |

| • Density | 180/km2 (480/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Placentino/a |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Postal code | 10600 |

| Website | www |

Plasencia (Spanish: [plaˈsenθja] ⓘ) is a municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Cáceres, Extremadura. As of 2013[update], it has a population of 41,047.

Plasencia is located in the Western-Central Iberian Peninsula, to the south of the Sistema Central. Housing primarily lies on the right bank of the Jerte. Plasencia is part of the so-called Ruta de la Plata, a north-south commercial path across Western Spain.

The founding is generally dated to the late 12th century, with Plasencia achieving its basic development during the late Middle Ages.[2]

History

[edit]Antiquity and the Middle Ages

[edit]Although Plasencia was not founded until 1186, pieces of pottery found in Boquique’s Cave provide evidence that this territory was inhabited long before. Pascual Madoz's dictionary details that this ancient territory, either called Ambroz or Ambracia, was originally given the name Ambrosia before becoming Plasencia.

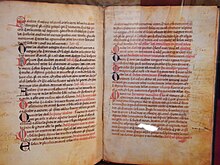

In the same year that the city was founded, Alfonso VIII of Castile gave the city its independence and the Diocese of Plasencia was created. The original motto of the city, Ut placeat Deo et Hominibus, means to please God and man. Ten years after its birth, Plasencia was taken over by the Almohad Caliphate, a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty that dominated the Iberian peninsula throughout much of the 12th century. King Alfonso VIII and his forces recaptured the city within the same day. At the end of the 13th century, the Charter of Plasencia was created, allowing the Christian, Muslim and Jewish people to live peacefully together within the city.[citation needed] At the end of the 14th century a Jewish community of around 50 families lived in Plasencia's Mota neighbourhood, around the synagogue.[3] The 13th century witnessed different degrees of tolerance. After a few decades of allowing the development of Jewish life, rights were limited. Jewish citizens were also subjected to additional taxes, especially concerning contributions to the royal treasury.[4]The Jewish cemetery still exists.[5]

The regimiento system of local government was established in the city by Alfonso XI of Castile on 11 January 1346.[6]

The 15th century was a vital period in Plasencia’s history, because it was at this time that a jurisdiction of lordship was established. In 1442, King John II of Castile gifted the city to the House of Zúñiga and its right to vote in the Cortes of Castile was lost. In 1446, the first university in Extremadura was installed in Plasencia, according to the wish of the Bishop. As a result, everyone from the surrounding areas who could afford to study in the university moved to Plasencia.

In the second half of the 15th century, Plasencia got caught up in some warlike affairs. Henry IV of Castile was deposed from the throne in favour of the infant Alfonso after the count of Plasencia stole the sword of this king’s wooden statue, signifying that without the sword, he had no power.

Later in the 15th century Joanna la Beltraneja and Afonso V of Portugal were married, making the former queen consort of Portugal, also becoming a claimant to the Crown of Castile.

In 1488, the duke died and his grandson, Álvaro de Zúñiga y Pérez de Guzmán, succeeded him. The nobility took advantage of this situation and rebelled against the House of Zúñiga, trying to recover the power that they had over Plasencia before it was gifted away. The Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, stood by them and made the revolt a success. Ferdinand swore to defend and protect the freedom and charters of Plasencia until his death.

Modern age

[edit]

Plasencia had a certain importance in the American conquest too. Doctors recommended this place to King Ferdinand as the healthiest place in his kingdom and the place where he should establish his residence. The monarch moved here in 1515, and died in Madrigalejo during his travel to Guadalupe.

In 1573, the Bishop of Plasencia, Pedro Ponce de León, donated a significant part of his own library to the monastery of El Escorial, and a decade later, another bishop had a library formed, containing more than 3,880 works in more than 10,000 volumes.

When the original 18 provinces of Castile arose in 1502, they were established according to their votes in the Cortes. There were no cities in Extremadura with the right of vote, because most of them were property of Salamanca. Due to this, the inhabitants of Plasencia decided to buy the right which they previously held, and asked other important cities such as Alcántara, Badajoz, Cáceres, Mérida and Trujillo to help them. This was the moment in which the province of Extremadura was formed.

Contemporary Age

[edit]

During the Peninsular War, Plasencia became a strategic location for French troops. In June 1808, uprisings occurred which ended up with the murder and lynching of afrancesados. Some time later, the inhabitants of Plasencia established a local military junta to defend their own interests; however, the city was overtaken and villages, such as Malpartida, were burnt down. French soldiers took control of Plasencia 12 times by forcible means and apart from the high number of buildings that were destroyed, the inhabitants too were also tortured and killed.

Once the Old Regime was abolished, Extremadura was divided into two different provinces: Cáceres and Badajoz. Plasencia argued with Cáceres about which of them should be the capital of the province, arguing that it had a higher number of population, it was more affluent and it had the bishop's palace. Despite these advantages, other traits were considered more important and Cáceres was chosen as the capital of the province.

The Restoration was a revolutionary era for Plasencia because the city witnessed many reforms that affected its economy and society. For the first time the city had a drinking water network, public lighting, and an improved sewer system. Furthermore, the agrarian economy evolved into an industrial one thanks to the railway station which was founded in the city. A curiosity of this period, the painter Joaquín Sorolla immortalized the city in his painting El mercado in 1917, in which you can see the landscape of the city from the river Jerte.

During the Spanish Civil War, the military uprising of 1936 led by Francisco Franco rapidly swept Plasencia. The Lieutenant Colonel José Puente took control of the city easily, and as a result, the Republican prisoners were forced to build one of the city’s most famous parks, The Pines Park.

The final chapter of the 20th century was an extraordinary period for Plasencia and its development; the number of inhabitants has tripled in the last 60 years, and during this period of time many public works have been constructed including the hospital Virgen del Puerto, the reservoir of Plasencia, the Municipal Sport Centre and many useful roads. In addition, several university degrees are offered at the present university campus.

-

The market, oil painting by Joaquín Sorolla showing an image of the city in 1917.

-

Alcázar of Plasencia before its demolition in 1941

Main sights

[edit]

- The double line of walls, with six gates and 68 towers, dating to 1197. The Keep (or Alcázar) was demolished in 1941.

- Remains of a 16C aqueduct, locally called Arcos de San Antón.

- Las Catedrales, a complex of two cathedrals. In 1189, by request of Alfonso VIII, Plasencia was declared head of dioceses by Pope Clement III and work on a Romanesque Cathedral started shortly after, concluding sometime in the 18th century, by which time fashions had changed and Gothic elements had been added in the forms of pointed arches to the Nave and a rose window to the main South Entrance, while the cloister, on the East side bordering the city walls, was entirely Gothic. In the 15th century the Dioceses decided to build a grand Gothic Cathedral in the same site, demolishing the old cathedral as the new one was being built. Work started in 1498 and by the 16th century, standard Renaissance elements had been added such as the East Entrance and the elaborate Choir Seating, while the local style of the period, Plateresque, is present in the West (main) and the Presbytery Entrances. Work continued until the 18th century, when, with only the Sanctuary and the Transept of the New Cathedral finished, the project was abandoned leaving behind a somewhat odd result, as most of the Nave of the Old Cathedral, its cloister and its unique Octagonal Tower housing the Sala Capitular Chapel is still attached to the New Cathedral, while the new choir, that was supposed to stand along the New Nave, was positioned across the transept. In the Main Chapel, there is an altarpiece by Gregorio Fernández (17th century), and the choir by Rodrigo Alemán.

- The Museum, near the Cathedral, is home to artworks by Jusepe de Ribera and Luis de Morales.

- Renaissance Town Hall, in the Plaza Mayor

- Casa consistorial (16th–18th centuries)

- Palacio de los marqueses de Mirabel (16th century) with a two-order court

- Church of San Martín (13th century). It has a nave and two aisles, and a retablo by Luis de Morales (1570).

- Church and convent of Santo Domingo (St. Dominic, mid-15th century)

- Church of San Esteban (15th century), with an apse in Gothic style. The high altar is transitional Plateresque-Baroque style.

- Sanctuary of Virgen del Puerto, some 5 kilometers from the city, begun in the 15th century but finished three centuries later.

- Nature resorts include the Monfragüe National Park.

- Canchos de Ramiro y Ladronera Protected Area.

Transportation

[edit]Plasencia had three city bus routes

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Plasencia, Spain (1981-2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.8 (53.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

21.7 (71.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.0 (41.0) |

11.1 (51.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 79.6 (3.13) |

61.0 (2.40) |

47.2 (1.86) |

59.2 (2.33) |

64.5 (2.54) |

22.5 (0.89) |

6.0 (0.24) |

6.0 (0.24) |

38.3 (1.51) |

96.9 (3.81) |

100.7 (3.96) |

103.2 (4.06) |

685.1 (26.97) |

| Average rainy days | 9.4 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 90.3 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[7] | |||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]

The specialities of the local cuisine include "migas" (breadcrumbs with Spanish sausage and bacon), casseroles, stews and tench, an exceptional freshwater game fish.

Festivals include:

- June fair, at the beginning of the month

- Martes Mayor, the first Tuesday of August

- Procession and Festivities of la Virgen del Puerto Plasencia, first Sunday after Easter Sunday

- Fair of the Cherry-tree in flower El Jerte Valley

Transport

[edit]See also

[edit]People

[edit]References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ Andrés Ordax, Salvador (1987). "Arte y urbanismo en Plasencia en la Edad Media" (PDF). Norba: Revista de arte (7): 47–48. ISSN 0213-2214.

- ^ "Plasencia". JGuide Europe. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Plasencia". JGuide Europe. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Plasencia". JGuide Europe. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Ruiz de la Peña Solar 1990, pp. 247, 263.

- ^ "World Weather Information Service – Plasencia". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- Bibliography

- Ruiz de la Peña Solar, Juan Ignacio (1990). "El régimen municipal de Plasencia en la Edad Media del concejo organizativo y autónomo al regimiento". Historia. Instituciones. Documentos (17). Seville: Universidad de Sevilla: 247–266. ISSN 0210-7716.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Ver Extremadura (in Spanish)

- Photos

- Plasencia is the subject of the Revealing Cooperation and Conflict Project trying to create a virtual 3D model and database describing the city in the time between 1390-1420 CE.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.