Portal:History/Featured article

| This Wikipedia page has been superseded by Portal:History and is retained primarily for historical reference. |

| Note: Article entries are now being transcluded directly on the main portal page. However, this page should be retained for historical reference. |

Process

[edit]This section uses the same layout template as the Selected biography section of this portal, as the two sections are the same in form if different in content. If you wish to add a new selection to the article, use the following template:

{{Portal:History/Featured article/Layout

|image=

|size=

|caption=

|text=

|link=

}}

Added articles should be Featured articles about prominent (or not so prominent) historical figures, and should be added to the first available slot, and afterwards the max= parameter on this section's {{Random portal component}} on the actual portal should be updated. A current list of eligible articles can be found here; biographies should instead be nominated to the Selected biography section. Try to avoid systematic bias; this section's selections were crafted to represent as wide a world view as possible. Lastly, if for some reason you wish to nominate a non-FA biography for inclusion, you can do so in the nominations section at the bottom of this page.

For the old by-month format, see older versions of this page.

Selections

[edit]Featured article 1

Portal:History/Featured article/1

The 1689 Boston revolt was a popular uprising on April 18, 1689, against the rule of Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of the Dominion of New England. A well-organized "mob" of provincial militia and citizens formed in the town of Boston, the capital of the dominion, and arrested dominion officials. Members of the Church of England were also taken into custody if they were believed to sympathize with the administration of the dominion. Neither faction sustained casualties during the revolt. Leaders of the former Massachusetts Bay Colony then reclaimed control of the government. In other colonies, members of governments displaced by the dominion were returned to power.Andros was commissioned governor of New England in 1686. He had earned the enmity of the populace by enforcing the restrictive Navigation Acts, denying the validity of existing land titles, restricting town meetings, and appointing unpopular regular officers to lead colonial militia, among other actions. Furthermore, he had infuriated Puritans in Boston by promoting the Church of England, which was rejected by many nonconformist New England colonists. (Full article...)

Featured article 2

Portal:History/Featured article/2

On 27 February 1962, the Independence Palace in Saigon, South Vietnam, was bombed by two dissident Republic of Vietnam Air Force pilots, Second Lieutenant Nguyễn Văn Cử and First Lieutenant Phạm Phú Quốc. The pilots targeted the building, the official residence of the President of South Vietnam, with the aim of assassinating President Ngô Đình Diệm and his immediate family, who acted as political advisors.The pilots later said they attempted the assassination in response to Diệm's autocratic rule, in which he focused more on remaining in power than on confronting the Viet Cong (VC), a Marxist–Leninist guerilla army who were threatening to overthrow the South Vietnamese government. Cử and Quốc hoped that the airstrike would expose Diệm's vulnerability and trigger a general uprising, but this failed to materialize. (Full article...)

Featured article 3

Portal:History/Featured article/3

Western Ganga was an important ruling dynasty of ancient Karnataka in India which lasted from about 350 to 999 CE. They are known as "Western Gangas" to distinguish them from the Eastern Gangas who in later centuries ruled over Kalinga (modern Odisha and Northern Andhra Pradesh). The general belief is that the Western Gangas began their rule during a time when multiple native clans asserted their freedom due to the weakening of the Pallava empire in South India, a geo-political event sometimes attributed to the southern conquests of Samudra Gupta. The Western Ganga sovereignty lasted from about 350 to 550 CE, initially ruling from Kolar and later, moving their capital to Talakadu on the banks of the Kaveri River in modern Mysore district.After the rise of the imperial Chalukyas of Badami, the Gangas accepted Chalukya overlordship and fought for the cause of their overlords against the Pallavas of Kanchi. The Chalukyas were replaced by the Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta in 753 CE as the dominant power in the Deccan. After a century of struggle for autonomy, the Western Gangas finally accepted Rashtrakuta overlordship and successfully fought alongside them against their foes, the Chola Dynasty of Tanjavur. In the late 10th century, north of Tungabhadra river, the Rashtrakutas were replaced by the emerging Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola Dynasty saw renewed power south of the Kaveri river. The defeat of the Western Gangas by Cholas around 1000 resulted in the end of the Ganga influence over the region. (Full article...)

Featured article 4

Portal:History/Featured article/4

The last voyage of HMCS Karluk, flagship of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, ended with the loss of the ship and the subsequent deaths of nearly half her complement. On her outward voyage in August 1913 Karluk, a brigantine formerly used as a whaler, became trapped in the Arctic ice while sailing to a rendezvous point at Herschel Island. After a long drift across the Beaufort and Chukchi seas, the ship was crushed and sunk. In the ensuing months the crew and expedition staff struggled to survive, first on the ice and later on the shores of Wrangel Island. In all, eleven men died before help could reach them.The Canadian Arctic Expedition was organised under the leadership of Canadian-born anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and had both scientific and geographic objectives. Shortly after Karluk was trapped, Stefansson and a small party left the ship, stating that they intended to hunt for caribou. As Karluk drifted from its fixed position, it became impossible for the hunting party to return; Stefansson then devoted himself to the expedition's other objectives, leaving the crew and staff aboard the ship under the charge of its captain, Robert Bartlett. After the sinking Bartlett organised a march to Wrangel Island, 80 miles (130 km) away. Conditions on the ice were difficult and dangerous; two parties of four men each were lost in the attempt to reach the island.

After the survivors had landed, Bartlett, accompanied by a single Inuk companion, set out across the ice to reach the Siberian coast. From there, after many weeks of arduous travel, Bartlett eventually arrived in Alaska, but ice conditions prevented any immediate rescue mission for the stranded party. They survived by hunting game, but were short of food and troubled by internal dissent. Before their rescue in September 1914, three more of the party had died, two of illness and one in violent circumstances.

Featured article 5

Portal:History/Featured article/5

The formal unification of Germany into a politically and administratively integrated nation state officially occurred on 18 January 1871 at the Versailles Palace's Hall of Mirrors in France. Princes of the German states gathered there to proclaim Wilhelm of Prussia as Emperor Wilhelm of the German Empire after the French capitulation in the Franco-Prussian War. Unofficially, the transition of most of the German-speaking populations into a federated organization of states occurred over nearly a century of experimentation. Unification exposed several glaring religious, linguistic, social, and cultural differences between and among the inhabitants of the new nation, suggesting that 1871 only represents one moment in a continuum of the larger unification processes.The model of diplomatic spheres of influence resulting from the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15 after the Napoleonic Wars endorsed Austrian dominance in Central Europe. However, the negotiators at Vienna took no account of Prussia's growing strength within and among the German states, failing to foresee that Prussia would challenge Austria for leadership within the German states. This German dualism presented two solutions to the problem of unification: Kleindeutsche Lösung, the small Germany solution (Germany without Austria), or Großdeutsche Lösung, greater Germany solution (Germany with Austria). Reaction to Danish and French nationalism provided foci for expressions of German unity. Military successes—especially Prussian ones—in three regional wars generated enthusiasm and pride that politicians could harness to promote unification. This experience echoed the memory of mutual accomplishment in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly in the War of Liberation of 1813–14. By establishing a Germany without Austria, the political and administrative unification in 1871 at least temporarily solved the problem of dualism.

Featured article 6

Portal:History/Featured article/6

The Treaty of Devol (Greek: συνθήκη της Δεαβόλεως) was an agreement made in 1108 between Bohemond I of Antioch and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, in the wake of the First Crusade. It is named after the Byzantine fortress of Devol in Macedonia (in modern Albania). Although the treaty was not immediately enforced, it was intended to make the Principality of Antioch a vassal state of the Byzantine Empire.At the beginning of the First Crusade, Crusader armies assembled at Constantinople and promised to return to the Byzantine Empire any land they might conquer. However, Bohemond, the son of Alexios' former enemy Robert Guiscard, claimed the Principality of Antioch for himself. Alexios did not recognize the legitimacy of the Principality, and Bohemond went to Europe looking for reinforcements. He launched into open warfare against Alexios, but he was soon forced to surrender and negotiate with Alexios at the imperial camp at Diabolis (Devol), where the Treaty was signed.

Under the terms of the Treaty, Bohemond agreed to become a vassal of the Emperor and to defend the Empire whenever needed. He also accepted the appointment of a Greek Patriarch. In return, he was given the titles of sebastos and doux (duke) of Antioch, and he was guaranteed the right to pass on to his heirs the County of Edessa. Following this, Bohemond retreated to Apulia and died there. His nephew, Tancred, who was regent in Antioch, refused to accept the terms of the Treaty. Antioch came temporarily under Byzantine sway in 1137, but it was not until 1158 that it truly became a Byzantine vassal.

Featured article 7

Portal:History/Featured article/7

To the People of Texas & All Americans in the World is an open letter written on February 24, 1836, by William B. Travis, commander of the Texian forces at the Battle of the Alamo, to settlers in Mexican Texas. The letter is renowned as a "declaration of defiance" and a "masterpiece of American patriotism", and forms part of the history education of Texas schoolchildren.On February 23, the Alamo Mission in San Antonio, Texas had been besieged by Mexican forces led by General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Fearing that his small group of men could not withstand an assault, Travis wrote this letter seeking reinforcements and supplies from supporters. The letter closes with Travis's vow of "Victory or Death!", an emotion which has been both praised and derided by historians.

The letter was initially entrusted to courier Albert Martin, who carried it to the town of Gonzales some seventy miles away. Martin added several postscripts to encourage men to reinforce the Alamo, and then handed the letter to Launcelot Smithers. Smithers added his own postscript and delivered the letter to its intended destination, San Felipe de Austin. Local publishers printed over 700 copies of the letter. It also appeared in the two main Texas newspapers and was eventually printed throughout the United States and Europe. Partially in response to the letter, men from throughout Texas and the United States began to gather in Gonzales. Between 32 and 90 of them reached the Alamo before it fell; the remainder formed the nucleus of the army which eventually defeated Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Featured article 8

Portal:History/Featured article/8

The exact nature of Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) of China is unclear. Analysis of the relationship is further complicated by modern political conflicts, and the application of Westphalian sovereignty to a time when the concept did not exist. Some Mainland Chinese scholars, such as Wang Jiawei & Nyima Gyaincain, assert that the Ming Dynasty had unquestioned sovereignty over Tibet, pointing to the Ming court's issuing of various titles to Tibetan leaders, Tibetans' full acceptance of these titles, and a renewal process for successors of these titles that involved traveling to the Ming capital. Scholars within the PRC also argue that Tibet has been an integral part of China since the 13th century, thus a part of the Ming Empire. But most scholars outside the PRC, such as Turrell V. Wylie, Melvin C. Goldstein, and Helmut Hoffman, say that the relationship was one of suzerainty, that Ming titles were only nominal, that Tibet remained an independent region outside Ming control, and that it simply paid tribute until the reign of Jiajing (1521–1566), who ceased relations with Tibet.Some scholars note that Tibetan leaders during the Ming frequently engaged in civil war and conducted their own foreign diplomacy with neighboring states such as Nepal. Some scholars underscore the commercial aspect of the Ming-Tibetan relationship, noting the Ming Dynasty's shortage of horses for warfare and thus the importance of the horse trade with Tibet. Others argue that the significant religious nature of the relationship of the Ming court with Tibetan lamas is underrepresented in modern scholarship. In hopes of reviving the unique relationship of the earlier Mongol leader Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294) and his spiritual superior Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280) of the Tibetan Sakya sect, the Ming Chinese Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424) made a concerted effort to build a secular and religious alliance with Deshin Shekpa (1384–1415), the Karmapa of the Tibetan Karma Kagyu. However, Yongle's attempts were unsuccessful.

Featured article 9

Portal:History/Featured article/9

The Sydney Riot of 1879 was a civil disorder that occurred at an early international cricket match. It took place in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, at the Association Ground, Moore Park, now known as the Sydney Cricket Ground, during a match between a touring English team captained by Lord Harris and New South Wales, led by Dave Gregory, who was also the captain of Australia. The riot was sparked by a controversial umpiring decision, when star Australian batsman Billy Murdoch was given out by George Coulthard, a Victorian employed by the Englishmen. The dismissal caused an uproar among the parochial spectators, many of whom surged onto the pitch and assaulted Coulthard and some English players. It was alleged that illegal gamblers in the New South Wales pavilion, who had bet heavily on the home side, encouraged the riot because the tourists were in a dominant position and looked set to win. Another theory given to explain the anger was that of intercolonial rivalry, that the New South Wales crowd objected to what they perceived to be a slight from a Victorian umpire.The pitch invasion occurred while Gregory halted the match by not sending out a replacement for Murdoch. The New South Wales skipper called on Lord Harris to remove umpire Coulthard, whom he considered to be inept or biased, but his English counterpart declined. The other umpire, Edmund Barton, defended Coulthard and Lord Harris, saying that the decision against Murdoch was correct and that the English had conducted themselves appropriately. Eventually, Gregory agreed to resume the match without the removal of Coulthard. However, the crowd continued to disrupt proceedings, and play was abandoned for the day. Upon resumption after the Sunday rest day, Lord Harris's men won convincingly by an innings.

Featured article 10

Portal:History/Featured article/10

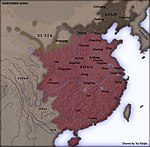

The Song dynasty (Chinese: 宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo; Wade–Giles: Sung Ch'ao; IPA: [sʊ̂ŋ tʂʰɑ̌ʊ̯]) was a ruling dynasty in China between 960 and 1279; it succeeded the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, and was followed by the Yuan dynasty. It was the first government in world history to issue banknotes or paper money, and a permanent standing navy. This dynasty also saw the first known use of gunpowder, as well as first discernment of true north using a compass.The Song Dynasty is divided into two distinct periods: the Northern Song and Southern Song. During the Northern Song (Chinese: 北宋, 960–1127), the Song capital was in the northern city of dongjing (now Kaifeng) and the dynasty controlled most of inner China. The Southern Song (Chinese: 南宋, 1127–1279) refers to the period after the Song lost control of northern China to the Jin dynasty. During this time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze river and established their capital at Lin'an (now Hangzhou). Although the Song dynasty had lost control of the traditional birthplace of Chinese civilization along the Yellow River, the Song economy was not in ruins, as the Southern Song Empire contained 60 percent of China's population and a majority of the most productive agricultural land. The Southern Song dynasty considerably bolstered its naval strength to defend its waters and land borders and to conduct maritime missions abroad.

Featured article 11

Portal:History/Featured article/11 The Second Crusade (1145–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade (1096–1099) by Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098. While it was the first Crusader state to be founded, it was also the first to fall.

The Second Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe. After crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuq Turks. The main Western Christian source, Odo of Deuil, and Syriac Christian sources claim that the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus secretly hindered the crusaders' progress, particularly in Anatolia where he is alleged to have deliberately ordered Turks to attack them. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and, in 1148, participated in an ill-advised attack on Damascus. The crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately have a key influence on the fall of Jerusalem and give rise to the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

The only success of the Second Crusade came to a combined force of 13,000 Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and German crusaders in 1147. Travelling from England, by ship, to the Holy Land, the army stopped and helped the smaller (7,000) Portuguese army in the capture of Lisbon, expelling its Moorish occupants.

Featured article 12

Portal:History/Featured article/12

The Rus' Khaganate is a name suggested for a polity that flourished during a poorly-documented period in the history of Eastern Europe (roughly the late 8th and early to mid-9th centuries AD). A predecessor to the Rurik Dynasty and the Kievan Rus', the Rus' Khaganate was a state (or a cluster of city-states) set up by a people called Rus', who might have been Norsemen (Vikings, Varangians), in what is today northern Russia. The region's population at that time was composed of Baltic, Slavic, Finnic, Turkic and Norse peoples. The region was also a place of operations for Varangians, eastern Scandinavian adventurers, merchants and pirates.According to contemporaneous sources, the population centers of the region, which may have included the proto-towns of Holmgard (Novgorod), Aldeigja (Ladoga), Lyubsha, Alaborg, Sarskoye Gorodishche, and Timerevo, were under the rule of a monarch or monarchs using the Old Turkic title Khagan. The Rus' Khaganate period marked the genesis of a distinct Rus' ethnos, and its successor states would include Kievan Rus' and later states from which modern Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine evolved.

Featured article 13

Portal:History/Featured article/13

Plymouth Colony was an English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691. The first settlement of the Plymouth Colony was at New Plymouth, a location previously surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement, which served as the capital of the colony, is today the modern town of Plymouth, Massachusetts. At its height, Plymouth Colony occupied most of the southeastern portion of the modern state of Massachusetts.Founded by a group of Separatists and Anglicans, who together later came to be known as the Pilgrims, Plymouth Colony was, along with Jamestown, Virginia, one of the earliest successful colonies to be founded by the English in North America and the first sizable permanent English settlement in the New England region. Aided by Squanto, a Native American of the Patuxet people, the colony was able to establish a treaty with Chief Massasoit which helped to ensure the colony's success. It played a central role in King Philip's War, one of the earliest of the Indian Wars. Ultimately, the colony was merged with the Massachusetts Bay Colony and other territories in 1691 to form the Province of Massachusetts Bay.

Despite the colony's relatively short history, Plymouth holds a special role in American history. Rather than being entrepreneurs like many of the settlers of Jamestown, a significant proportion of the citizens of Plymouth were fleeing religious persecution and searching for a place to worship as they saw fit. The social and legal systems of the colony became closely tied to their religious beliefs, as well as English custom. Many of the people and events surrounding Plymouth Colony have become part of American folklore, including the North American tradition known as Thanksgiving and the monument known as Plymouth Rock.

Featured article 14

Portal:History/Featured article/14

The Act of Independence of Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos Nepriklausomybės Aktas) or Act of February 16 was signed by the Council of Lithuania on February 16, 1918, proclaiming the restoration of an independent State of Lithuania, governed by democratic principles, with Vilnius as its capital. The Act was signed by all twenty representatives, chaired by Jonas Basanavičius. The Act of February 16 was the end result of a series of resolutions on the issue, including one issued by the Vilnius Conference and the Act of January 8. The path to the Act was long and complex because the German Empire exerted pressure on the Council to form an alliance. The Council had to carefully maneuver between the Germans, whose troops were present in Lithuania, and the demands of the Lithuanian people.The immediate effects of the announcement of Lithuania's re-establishment of independence were limited. Publication of the Act was prohibited by the German authorities, and the text was distributed and printed illegally. The work of the Council was hindered, and Germans remained in control over Lithuania. The situation changed only when Germany lost World War I in the fall of 1918. In November 1918 the first Cabinet of Lithuania was formed, and the Council of Lithuania gained control over the territory of Lithuania. Independent Lithuania, although it would soon be battling the Wars of Independence, became a reality.

Featured article 15

Portal:History/Featured article/15

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Soviet Communist dominance, imposed after the end of World War II in the Polish People's Republic. These years, while featuring many improvements in the standard of living in Poland, were marred by social unrest and economic depression.Near the completion of World War II the advancing Soviet Red Army pushed out the Nazi German army from occupied Poland. At the insistence of Joseph Stalin, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a new Polish provisional and pro-Communist coalition government in Moscow, which ignored the Polish government-in-exile based in London. This has been described as a Western betrayal of Poland on the part of Allied Powers to appease the Soviet leader and avoid a direct conflict. The Potsdam Agreement of 1945 ratified the westerly shift of Polish borders and approved its new territory between the Oder–Neisse line and the Curzon Line. Poland, as a result of World War II, for the first time in history became an ethnically homogeneous nation state without prominent minorities due to destruction of indigenous Polish-Jewish population in the Holocaust, the flight and expulsion of Germans in the west, resettlement of Ukrainians in the east, and the repatriation of Poles from Kresy. The new communist government in Warsaw solidified its political power over the next two years, while the Communist Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) under Bolesław Bierut gained firm control over the country, which would become part of the postwar Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. Following Stalin's death in 1953, a political "thaw" in Eastern Europe caused a more liberal faction of the Polish Communists of Władysław Gomułka to gain power. By the mid-1960s, Poland began experiencing increasing economic, as well as political, difficulties. In December 1970, a price hike led to a wave of strikes. The government introduced a new economic program based on large-scale borrowing from the West, which resulted in an immediate rise in living standards and expectations, but the program faltered because of the 1973 oil crisis. In the late 1970s the government of Edward Gierek was finally forced to raise prices, and this led to another wave of public protests.

Featured article 16

Portal:History/Featured article/16

The Byzantine Empire (or Byzantium) was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the "Roman Empire" (Greek: Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, Basileia Rhōmaiōn) or Romania (Ῥωμανία) to its inhabitants and neighbours, it was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State and maintained Roman state traditions. Byzantium is today distinguished from ancient Rome proper insofar as it was oriented towards Greek culture, characterised by Christianity rather than Roman paganism and was predominantly Greek-speaking rather than Latin-speaking.The Byzantine Empire existed for more than a thousand years, from its genesis in the 4th century to 1453. During most of its existence, it remained one of the most powerful economic, cultural, and military forces in Europe, despite setbacks and territorial losses, especially during the Arab–Byzantine wars. The Empire recovered during the Macedonian dynasty, rising again to become a preeminent power in the Eastern Mediterranean by the late 10th century, rivalling the Fatimid Caliphate.

After 1071, however, much of Asia Minor, the Empire's heartland, was lost to the Seljuq Turks. The Komnenian restoration regained some ground and briefly reestablished dominance in the 12th century, but following the death of Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos (r. 1183–85) and the end of the Komnenos dynasty in the late 12th century the Empire declined again. The Empire received a mortal blow in 1204 from the Fourth Crusade, when it was dissolved and divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms.

Successive civil wars in the 14th century further sapped the Empire's strength, and most of its remaining territories were lost in the Byzantine–Ottoman Wars, which culminated in the Fall of Constantinople and the conquest of remaining territories by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century.

Featured article 17

Portal:History/Featured article/17

The inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre were held in AD 80, on the orders of the Roman Emperor Titus, to celebrate the completion of the Colosseum, then known as the Flavian Amphitheatre (Latin: Amphitheatrum Flavium). Vespasian began construction of the amphitheatre around AD 70, and it was completed by Titus soon after Vespasian's death in AD 79. After Titus' reign began with months of disasters – including the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a fire in Rome, and an outbreak of plague – he inaugurated the building with lavish games which lasted for more than a hundred days, perhaps partially in an attempt to appease the Roman public and the gods.Little documentary evidence of the nature of the games (ludi) remains. They appear to have followed the standard format of the Roman games: animal entertainments in the morning session, followed by the executions of criminals around midday, with the afternoon session reserved for gladiatorial combats and recreations of famous battles. The animal entertainments, which featured creatures from throughout the Roman Empire, included extravagant hunts and fights between different species. Animals also played a role in some executions which were staged as recreations of myths and historical events. Naval battles formed part of the spectacles but whether these took place in the amphitheatre or on a lake that had been specially constructed by Augustus is a topic of debate among historians.

Featured article 18

Portal:History/Featured article/18

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3500 BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology) with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh. The history of ancient Egypt occurred in a series of stable Kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as Intermediate Periods: the Old Kingdom of the Early Bronze Age, the Middle Kingdom of the Middle Bronze Age and the New Kingdom of the Late Bronze Age. Egypt reached the pinnacle of its power during the New Kingdom, in the Ramesside period, after which it entered a period of slow decline. Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers in this late period. In the aftermath of Alexander the Great's death, one of his generals, Ptolemy Soter, established himself as the new ruler of Egypt. This Ptolemaic Dynasty ruled Egypt until 30 BC, when it fell to the Roman Empire and became a Roman province.The success of ancient Egyptian civilization came partly from its ability to adapt to the conditions of the Nile River Valley. The predictable flooding and controlled irrigation of the fertile valley produced surplus crops, which fueled social development and culture. With resources to spare, the administration sponsored mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions, the early development of an independent writing system, the organization of collective construction and agricultural projects, trade with surrounding regions, and a military intended to defeat foreign enemies and assert Egyptian dominance. Motivating and organizing these activities was a bureaucracy of elite scribes, religious leaders, and administrators under the control of a Pharaoh who ensured the cooperation and unity of the Egyptian people in the context of an elaborate system of religious beliefs.

Featured article 19

Portal:History/Featured article/19

The history of the U.S. state of Minnesota is shaped by its original Native American residents, European exploration and settlement, and the emergence of industries made possible by the state's natural resources. Minnesota achieved prominence through fur trading, logging, and farming, and later through railroads, and iron mining. While those industries remain important, the state's economy is now driven by banking, computers, and health care.The earliest known settlers followed herds of large game to the region during the last glacial period. They preceded the Anishinaabe, the Dakota, and other Native American inhabitants. Fur traders from France arrived during the 17th century. Europeans, moving west during the 19th century, drove out most of the Native Americans. Fort Snelling, built to protect United States territorial interests, brought early settlers to the area. Early settlers used Saint Anthony Falls for powering sawmills in the area that became Minneapolis, while others settled downriver in the area that became Saint Paul.

Minnesota became a part of the United States as Minnesota Territory in 1849, and became the 32nd U.S. state on May 11, 1858. After the upheaval of the American Civil War and the Dakota War of 1862, the state's economy started to develop when natural resources were tapped for logging and farming. Railroads attracted immigrants, established the farm economy, and brought goods to market. The power provided by Saint Anthony Falls spurred the growth of Minneapolis, and the innovative milling methods gave it the title of the "milling capital of the world."

Featured article 20

Portal:History/Featured article/20

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I of England and VI of Scotland by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby.The plan was to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of England's Parliament on 5 November 1605, as the prelude to a popular revolt in the Midlands during which James's nine-year-old daughter, Princess Elizabeth, was to be installed as the Catholic head of state. Catesby may have embarked on the scheme after hopes of securing greater religious tolerance under King James had faded, leaving many English Catholics disappointed. His fellow plotters were John Wright, Thomas Wintour, Thomas Percy, Guy Fawkes, Robert Keyes, Thomas Bates, Robert Wintour, Christopher Wright, John Grant, Sir Ambrose Rookwood, Sir Everard Digby and Francis Tresham. Fawkes, who had 10 years of military experience fighting in the Spanish Netherlands in suppression of the Dutch Revolt, was given charge of the explosives.

The plot was revealed to the authorities in an anonymous letter sent to William Parker, 4th Baron Monteagle, on 26 October 1605. During a search of the House of Lords at about midnight on 4 November 1605, Fawkes was discovered guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder—enough to reduce the House of Lords to rubble—and arrested. Most of the conspirators fled from London as they learnt of the plot's discovery, trying to enlist support along the way. Several made a stand against the pursuing Sheriff of Worcester and his men at Holbeche House; in the ensuing battle Catesby was one of those shot and killed. At their trial on 27 January 1606, eight of the survivors, including Fawkes, were convicted and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

Featured article 21

Portal:History/Featured article/21

A South American dreadnought race involving Argentina, Brazil, and Chile began when the Brazilian government announced its intention to purchase three dreadnoughts—powerful battleships whose capabilities far outstripped older vessels in the world's navies—in 1907. Two ships of the Minas Geraes class were laid down immediately with a third to follow. The Argentine and Chilean governments immediately canceled a naval-limiting pact between them, and both ordered two dreadnoughts (the Rivadavia and Almirante Latorre classes, respectively). Meanwhile, Brazil's third dreadnought was canceled in favor of an even larger ship, but the ship was laid down and ripped up several times after repeated major alterations to the design. When the Brazilian government finally settled on a design, they realized it would be outclassed by the Chilean dreadnoughts' larger armament, so they sold the partly-completed ship to the Ottoman Empire and attempted to acquire a more powerful vessel. By this time the First World War had broken out in Europe, and many shipbuilders suspended work on dreadnoughts for foreign countries, halting the Brazilian plans. Argentina's two dreadnoughts were delivered, as the United States remained neutral in the opening years of the war, but Chile's two dreadnoughts were purchased by the United Kingdom. In the years between the First and Second World War, many naval expansion plans, some involving dreadnought purchases, were proposed. While most never came to fruition, in April 1920 the Chilean government reacquired one of the dreadnoughts taken over by the United Kingdom. No other dreadnoughts were purchased by a South American nation, and all were sold for scrap in the 1950s.Featured article 22

Portal:History/Featured article/22

The Mormon handcart pioneers were participants in the westward migration of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who used handcarts to transport their supplies and belongings while walking from Iowa or Nebraska to Utah. The Mormon handcart movement began in 1856 and lasted until 1860.Motivated to join their fellow Church members in avoiding persecution but lacking funds for full ox or horse teams, nearly 3,000 Mormon pioneers from England, Wales, and Scandinavia made the journey to Utah in 10 handcart companies. For two of them, the Willie and Martin handcart companies, the trek led to disaster after they started their journey dangerously late and were caught by heavy snow and bitterly cold temperatures in the Rocky Mountains of central Wyoming. Despite a dramatic rescue effort, more than 210 of the 980 pioneers in the two companies died along the way.

Although fewer than ten percent of the 1847–68 Latter-day Saint emigrants made the journey west using handcarts, the handcart pioneers have become an important symbol in LDS culture, representing the faithfulness, courage, determination, and sacrifice of the pioneer generation. The handcart treks were a familiar theme in 19th century Mormon folk music and handcart pioneers continue to be recognized and honored in events such as Pioneer Day, Church pageants, and similar commemorations.

Featured article 23

Portal:History/Featured article/23

Medieval cuisine includes foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the Middle Ages, which lasted from the fifth to the fifteenth century. During this period, diets and cooking changed less than they did in the early modern period that followed, when those changes helped lay the foundations for modern European cuisine.Cereals remained the most important staple during the early Middle Ages as rice was introduced late, and the potato was only introduced in 1536, with a much later date for widespread consumption. Barley, oat and rye were eaten by the poor. Wheat was for the governing classes. These were consumed as bread, porridge, gruel and pasta by all of society's members. Fava beans and vegetables were important supplements to the cereal-based diet of the lower orders. (Phaseolus beans, today the "common bean", were of New World origin and were introduced after the Columbian exchange in the 16th century.)

A type of refined cooking developed in the late Middle Ages that set the standard among the nobility all over Europe. Common seasonings in the highly spiced sweet-sour repertory typical of upper-class medieval food included verjuice, wine and vinegar in combination with spices such as black pepper, saffron and ginger. These, along with the widespread use of sugar or honey, gave many dishes a sweet-sour flavor. Almonds were very popular as a thickener in soups, stews, and sauces, particularly as almond milk.

Nominations

[edit]Currently none.