Rabbits and hares in art

Rabbits and hares (Leporidae) are common motifs in the visual arts, with variable mythological and artistic meanings in different cultures. The rabbit as well as the hare have been associated with moon deities and may signify rebirth or resurrection.[1] They may also be symbols of fertility or sensuality, and they appear in depictions of hunting and spring scenes in the Labours of the Months.

Judaism

[edit]

In Judaism, the rabbit is considered an unclean animal, because "though it chews the cud, does not have a divided hoof."[2][note 1] This led to derogatory statements in the Christian art of the Middle Ages, and to an ambiguous interpretation of the rabbit's symbolism. The "shafan" in Hebrew has symbolic meaning. Although rabbits were a non-kosher animal in the Bible, positive symbolic connotations were sometimes noted, as for lions and eagles. 16th century German scholar Rabbi Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, saw the rabbits as a symbol of the Diaspora. In any case, a three hares motif was a prominent part of many Synagogues.[1][3]

Classical Antiquity

[edit]In Classical Antiquity, the hare, because it was prized as a hunting quarry, was seen as the epitome of the hunted creature that could survive only by prolific breeding. Herodotus,[4] Aristotle, Pliny and Claudius Aelianus all described the rabbit as one of the most fertile of animals. It thus became a symbol of vitality, sexual desire and fertility. The hare served as an attribute of Aphrodite and as a gift between lovers. In late antiquity it was used as a symbol of good luck and in connection with ancient burial traditions.

Christian art

[edit]

In Early Christian art, hares appeared on reliefs, epitaphs, icons and oil lamps although their significance is not always clear.

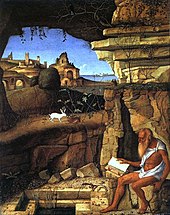

The Physiologus, a resource for medieval artists, states that when in danger the rabbit seeks safety by climbing high up rocky cliffs, but when running back down, because of its short front legs, it is quickly caught by its predators.[5] Likewise, according to the teaching of St. Basil, men should seek his salvation in the rock of Christ, rather than descending to seek worldly things and falling into the hands of the devil. The negative view of the rabbit as an unclean animal, which derived from the Old Testament, always remained present for medieval artists and their patrons. Thus the rabbit can have a negative connotation of unbridled sexuality and lust or a positive meaning as a symbol of the steep path to salvation. Whether a representation of a hare in Medieval art represents man falling to his doom or striving for his eternal salvation is therefore open to interpretation, depending on context.

The Hasenfenster (hare windows) in Paderborn Cathedral and in the Muotathal Monastery in Switzerland, in which three hares are depicted with only three ears between them, forming a triangle, can be seen as a symbol of the Trinity, and probably go back to an old symbol for the passage of time. Though they have six ears, the three hares shown in Albrecht Dürer's woodcut, The Holy Family with Three Hares (1497), can also be seen as a symbol of the Trinity.[citation needed]

The idea of rabbits as a symbol of vitality, rebirth and resurrection derives from antiquity. This explains their role in connection with Easter, the resurrection of Christ. The unusual presentation in Christian iconography of a Madonna with the Christ Child playing with a white rabbit in Titian's Madonna of the Rabbit can thus be interpreted Christologically. Together with the basket of bread and wine, a symbol of the sacrificial death of Christ, the picture may be interpreted as the resurrection of Christ after death.

The phenomenon of superfetation, where embryos from different menstrual cycles are present in the uterus, results in hares and rabbits being able to give birth seemingly without having been impregnated, which caused them to be seen as symbols of virginity.[6] Rabbits also live underground, an echo of the tomb of Christ.

As a symbol of fertility, white rabbits appear on a wing of the high altar in Freiburg Minster. They are playing at the feet of two pregnant women, Mary and Elizabeth. Martin Schongauer's engraving Jesus after the Temptation (1470) shows nine (three times three) rabbits at the feet of Jesus Christ, which can be seen as a sign of extreme vitality. In contrast, the tiny squashed rabbits at the base of the columns in Jan van Eyck's Rolin Madonna symbolize "Lust", as part of a set of references in the painting to all the Seven Deadly Sins.[7]

Hunting scenes in the sacred context can be understood as the pursuit of good through evil. In the Romanesque sculpture (c. 1135) in the Königslutter imperial Cathedral, a hare pursued by a hunter symbolises the human soul seeking to escape persecution by the devil. Another painting, Hares Catch the Hunters, shows the triumph of good over evil. Alternatively, when an eagle pursues the hare, the eagle can be seen as symbolizing Christ and the hare, uncleanliness and the evil's terror in the face of the light.

In Christian iconography, the hare is an attribute of Saint Martin of Tours and Saint Alberto di Siena, because legend has it that both protected hares from persecution by dogs and hunters. They are also an attribute of the patron saint of Spanish hunters, Olegarius of Barcelona. White hares and rabbits were sometimes the symbols of chastity and purity.[8]

In secular art

[edit]

In non-religious art of the modern era, the rabbit appears in the same context as in antiquity: as prey for the hunter, or representing spring or autumn, as well as an attribute of Venus and a symbol of physical love. In cycles of the Labours of the Months, rabbits frequently appear in the spring months. In Francesco del Cossa's painting of April in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara, Italy, Venus' children, surrounded by a flock of white rabbits, symbolize love and fertility.

In Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, rabbits are depicted more often than hares. In an allegory on lust by Pisanello, a naked woman lies on a couch with a rabbit at her feet. Pinturicchio's scene of Susanna in the Bath is displayed in the Vatican's Borgia Apartment. Here, each of the two old men are accompanied by a pair of hares or rabbits, clearly indicating wanton lust. In Piero di Cosimo's painting of Venus and Mars, a cupid resting on Venus clings to a white rabbit for similar reasons.

Still lifes in Dutch Golden Age painting and their Flemish equivalents often included a moralizing element which was understood by their original viewers without assistance: fish and meat can allude to religious dietary precepts, fish indicating fasting while great piles of meat indicate voluptas carnis (lusts of the flesh), especially if lovers are also depicted. Rabbits and birds, perhaps in the company of carrots and other phallic symbols, were easily understood by contemporary viewers in the same sense.

As small animals with fur, hares and rabbits allowed the artist to showcase his ability in painting this difficult material. Dead hares appear in the works of the earliest painter of still life collections of foodstuffs in a kitchen setting, Frans Snyders, and remain a common feature, very often sprawling hung up by a rear leg, in the works of Jan Fyt, Adriaen van Utrecht and many other specialists in the genre. By the end of the 17th century, the grander subgenre of the hunting trophy still life appeared, now set outdoors, as though at the back door of a palace or hunting lodge. Hares (but rarely rabbits) continued to feature in the works of the Dutch and Flemish originators of the genre, and later French painters like Jean-Baptiste Oudry.[9]

From the Middle Ages until modern times, the right to hunt was a vigorously defended privilege of the ruling classes. Hunting Still lifes, often in combination with hunting equipment, adorn the rooms of baroque palaces, indicating the rank and prestige of their owners. Jan Weenix' painting shows a still life reminiscent of a trophy case with birds and small game, fine fruits, a pet dog and a pet monkey, arranged in front of a classicising garden sculpture with the figure of Hercules and an opulent palace in the background. The wealth and luxurious lifestyle of the patron or owner is clearly shown.

The children's tales of the English author Beatrix Potter, illustrated by herself, include several titles featuring the badly behaved Peter Rabbit and other rabbit characters, including her first and most successful book The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), followed by The Tale of Benjamin Bunny (1904), and The Tale of The Flopsy Bunnies (1909). Potter's anthropomorphic clothed rabbits are probably the most familiar artistic rabbits in the English-speaking world, no doubt influenced by illustrations by John Tenniel of the White Rabbit in Lewis Carroll's book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Joseph Beuys, who always finds a place for a rabbit in his works, sees it as symbolizing resurrection. In the context of his action "How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare", he stated that the rabbit "...has a direct relationship to birth... For me, the rabbit is the symbol of incarnation. Because the rabbit shows in reality what man can only show in his thoughts. He buries himself, he buries himself in a depression. He incarnates himself in the earth, and that alone is important."

Masquerade (book) (1979), written and illustrated by the artist Kit Williams, is ostensibly a children's book, but contains elaborate clues to the location of a jewelled golden hare, also made by Williams, which he had buried at the location in England to which the clues in the book led. The hare was not found until 1982, in what later emerged as dubious circumstances.

The Welsh sculptor Barry Flanagan (1944-2009) was best known for his energetic bronzes of hares, which he produced throughout his career. Many have a comic element, and the length and thinness of the hare's body is often exaggerated.

Dürer's Young Hare

[edit]

Probably one of the most famous depictions of an animal in the history of European art is the painting Young Hare by Albrecht Dürer, completed in 1502 and now preserved in the Albertina in Vienna. Dürer's watercolor is seen in the context of his other nature studies, such as his almost equally famous Meadow or his Bird Wings. He chose to paint these in watercolor or gouache, striving for the highest possible precision and "realistic" representation.

The hare pictured by Dürer probably does not have a symbolic meaning, but it does have an exceptional reception history. Reproductions of Dürer's Hare have often been a permanent component of bourgeois living rooms in Germany. The image has been printed in textbooks; published in countless reproductions; embossed in copper, wood or stone; represented three-dimensionally in plastic or plaster; encased in plexiglas; painted on ostrich eggs; printed on plastic bags; surreally distorted in Hasengiraffe ("Haregiraffe") by Martin Missfeldt;[10] reproduced as a joke by Fluxus artists;[11] and cast in gold; or sold cheaply in galleries and at art fairs

Since early 2000, Ottmar Hörl has created several works based on Dürer's Hare, including a giant pink version.[12] Sigmar Polke has also engaged with the hare on paper or textiles, or as part of his installations,[13] and even in rubber band form.[14] Dieter Roth's Köttelkarnikel ("Turd Bunny") is a copy of Dürer's Hare made from rabbit droppings,[15] and Klaus Staeck enclosed one in a little wooden box, with a cutout hole, so that it could look out and breathe. Dürer's Hare has even inspired a depiction of the mythological Wolpertinger.

Depictions of Mary Toft Birthing Rabbits

[edit]William Hogarth depicted Mary Toft giving birth to rabbits in 1726 in the etchings Cunicularii or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation (1726) and Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism (1762).[16][17][18] Mary Toft was a woman who convinced many medical professionals and the public at the time that she was birthing rabbits, when it was, in fact, a hoax.[19] Inspired by the work of William Hogarth, artist Amelia Biewald resurrected the story of Mary Toft into the gallery with The Curious Case of Mary Toft in 2020.[20][21][22]

The Rabbit in Chinese Art

[edit]The earliest depiction of the rabbit in Chinese art dates back to the Neolithic period (7000-1700 B.C.) . The 5,000 year old jade, ornament rabbit was found at the Lingjiatan site in what is now the eastern Chinese province of Anhui.[23]

Rabbits have rich symbolic meanings in Chinese culture and art. They are considered gentle, intelligent, and very resourceful creatures; directly reflecting qualities admired in Chinese culture. Some key aspects include:[24]

- Longevity and Immortality: The rabbit is closely linked to the moon and the Moon Goddess, Chang’e, as well as the legend of the Jade Rabbit or the Moon Rabbit. The Jade Rabbit is believed to pound the elixir of immortality, making it a symbol of long life and eternal youth.

- Fertility and Abundance: With their high reproductive rates, rabbits have become a symbol of fertility and prosperity. They are often depicted in art during celebrations of renewal, such as the Lunar New Year or the spring season

- Grace and Kindness: Rabbits are known to be gentle and kind animals as well as embodying elegance and sensitivity. They resonate with the Confucian ideas and moral virtue and harmony.

- Good Fortune and Luck: In Chinese culture, the rabbit is considered to bring good luck and fortune. It is also the zodiac animal for people born in the Year of the Rabbit, which is associated with qualities like compassion, creativity, and diplomacy.

- Yin and Feminine Energy: Known as a lunar creature, the rabbit is connected to yin energy, which represents femininity, intuition, and tranquility.

Rabbits were not only celebrated in folk art but were also highly valued by Chinese literati for centuries. Writers and painters expressed both an affinity for and a profound gratitude toward the animal, as one of the Four Treasures of the Study—the inkbrush—was often crafted with rabbit hair. For millennia, rabbit hairs played a crucial role in shaping Chinese literary expression and history. Ancient Astronomers believed that the shadows on the moons surface resembled a rabbit, giving birth to the legend of the Jade Rabbit or Moon Rabbit. Legend has it that the Jade Rabbit was the companion of Chang’e, the Moon Goddess, providing each other solace in the cold solitude of the moon palace.[25] Such an evocative tale naturally inspired China’s literary and artistic masters, who couldn’t resist reinterpreting it in their works. Even the renowned poets Li Bai and Du Fu penned poems retelling the story of the Jade Rabbit; the legend influenced artists for years.

In Chinese art, rabbits often appear in paintings, ceramics, and carvings, depicted alongside the moon, other zodiac animals, or auspicious motifs to convey deeper meanings.[23]

Gallery

[edit]-

Pisanello: Vision of St. Eustace, 1435

-

Edwin Landseer, Scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream. Titania and Bottom with white rabbits, 1851

-

Feeding white rabbits, Frederick Morgan, Paris

-

The White Rabbit from Alice in Wonderland

-

Rabbits eating grapes

-

Ferdinand du Puigaudeau, Chinese Schadows, the Rabbit

-

Boy and Rabbit, by Henry Raeburn 1814

-

Zan Zig performing with rabbit and roses, magician poster, 1899

-

White rabbit standing, by Jan Mankes, 1910

-

Cunicularii or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation, William Hogarth, 1726

-

Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, William Hogarth, 1762

-

The Curious Case of Mary Toft, Wallpaper, Amelia Biewald, 2019

- Sculptures and objects representing rabbits and hares

-

Rabbit-shaped incense burner, Japan, 19th century

-

Japanese tsuba sword fitting with a "Rabbit Viewing the Autumn Moon", bronze, gold and silver, between 1670 and 1744

-

Rabbit Figurine

-

Tureen, 1754, Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, England

-

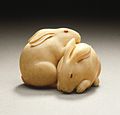

Netsuke with rabbit

- Sculptures representing rabbits and hares

-

The Rabbit statue is one of the 12 Chinese zodiac portrayed in the Kowloon Walled City Park in Kowloon City, Hong Kong

-

Jose de Creeft, Statue of Alice in Central Park, 1959

-

Bronze hare by Barry Flanagan, in Dublin

-

Der Hase by Jürgen Goertz in Nuremberg

See also

[edit]- How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare

- List of fictional hares and rabbits

- Moon gazing hare

- Moon rabbit

- Rabbits in culture and literature

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Hebrew, the rock hyrax is called שפן סלע (shafan sela), meaning rock "shafan", where the meaning of shafan is obscure, but is colloquially used as a synonym for rabbit in modern Hebrew.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Windling, Terri (2005). "The Symbolism of Rabbits and Hares". Endicott Studio. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- ^ Leviticus 11:6, cf. Deuteronomy 14:7

- ^ Wonnenberg, Felice Naomi. "How do the rabbits get into the synagogue? From China via Middle East and Germany to Galizia: On the tracks of the ROTATING RABBITS SYMBOL". googlepages.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories 3.108

- ^ Physiologus. Ed. by Ursula Treu. 3rd edition. Hanau 1998. pp. 103–104 (German).

- ^ Lumpkin, Susan; John Seidensticker (2011). Rabbits: The Animal Answer Guide. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-9789-0. p. 122.

- ^ Harbison, Craig. Jan van Eyck, The Play of Realism, p. 114, Reaktion Books, London, 1991, ISBN 0-948462-18-3

- ^ "the-symbolism-of-rabbits-and-hares". bunniesinbaskets.org. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Talbot, William S., "Jean-Baptiste Oudry: Hare and Leg of Lamb", p. 150, The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Vol. 57, No. 5 (May, 1970), pp. 149-158 , Cleveland Museum of Art, JSTOR

- ^ "Hase nach Albrecht Dürer". www.martin-missfeldt.de.

- ^ "Wie erklärt man einem toten Hasen die Kunst (How to explain art to a dead hare) Fluxus-Aktion" (in German). Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Smyth, Debbie (26 March 2015). "Pink Rabbit!". Travel with Intent. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Illustration, Gouache on patterned fabric".

- ^ Butler, Sharon (5 June 2012). "More on Prince, Polke, and rubber bands". Two Coats of Paint. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Multimedial: Künstler Roth". leben.freenet.de.

- ^ The curious case of Mary Toft. University of Glasgow Library Special Collections Department. (2009). https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/aug2009.html

- ^ Krysmanski, B. (1998). We see a ghost: Hogarth’s satire on methodists and.. Art Bulletin, 80(2), 292.

- ^ "print; satirical print | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Mary Toft of Goldyman, England, and Her Extraordinary Delivery of Seventeen Rabbits in 1726. (1980). Pediatrics, 66(4), 539.

- ^ "Amelia Biewald". Maake Magazine. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ Rosalux (17 November 2022). "ARTIST 2 ARTIST with Amelia Biewald". Rosalux Gallery. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ "The Curious Case Of Mary Toft |". www.ameliabiewald.com. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b Tone, Sixth (21 January 2023). "A Bunny Hop Through Centuries of Chinese Art". #SixthTone. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Hand, Jo-Lene (6 January 2023). "Symbolism of the Rabbit". Tao Group Hospitality. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ "The Moon Rabbit Legend: Exploring Japan's Enchanting Lunar Story". Bokksu. 14 August 2024. Retrieved 9 December 2024.

- ^ Slifkin, Nosson (1 March 2004). Shafan – The Hyrax (PDF). Southfield, MI; Nanuet, NY: Zoo Torah in association with Targum/Feldheim Distributed by Feldheim. pp. 99–135. ISBN 978-1-56871-312-0. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

Literature

[edit]- Guy de Tervarent: Attributs et symboles dans l'art profane. Genève 1997. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-2-600-00507-4

- Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie. Established by Engelbert Kirschbaum. Ed. Wolfgang Braunfels. Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1968–1976. ISBN 978-3-451-22568-0

External links

[edit]- Windling, Terri (2005). "The Symbolism of Rabbits and Hares". Endicott Studio. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- Online-Kunst.de on hares in the arts (in German)

- Article "Hase" in: Kunstlexikon by P. W. Hartmann (in German)

- Wie erklärt man einem toten Hasen die Kunst (How to explain art to a dead hare) Fluxus-Aktion (in German)