Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217

N25RM, the aircraft involved in the accident | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | December 4, 1978 |

| Summary | Crashed after loss of control in severe weather conditions |

| Site | Buffalo Pass, near Steamboat Springs, Colorado 40°32′12″N 106°39′50″W / 40.53667°N 106.66389°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 |

| Operator | Rocky Mountain Airways |

| IATA flight No. | JC217 |

| ICAO flight No. | RMA217 |

| Call sign | ROCKY MOUNTAIN 217 |

| Registration | N25RM |

| Flight origin | Steamboat Springs Airport, Colorado, United States |

| Destination | Stapleton International Airport, Colorado, United States |

| Occupants | 22 |

| Passengers | 20 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Injuries | 20 |

| Survivors | 20 |

Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217, referred to in the media as the "Miracle on Buffalo Pass",[1][2] was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from Steamboat Springs, Colorado to Denver that crashed on Buffalo Pass. The aircraft, a de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300, impacted terrain on a gentle slope and was partially buried in snow. All of the 22 passengers and crew survived the impact, but a female passenger died before rescue could arrive, and the captain died of his injuries 3 days after the accident. The investigation determined that the accident was caused by the formation of ice on the wings combined with downdrafts associated with a mountain wave led to the aircraft's loss of control and impact with terrain.[3]

Aircraft

[edit]The aircraft involved in the accident was a 5-year-old de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300, with registration N25RM and manufacturer serial number 387. It was powered by two Pratt & Whitney model PT6A-27 turboprop engines. The aircraft had flown for 15,145 hours before its final flight.[3][4] It was not equipped with a cockpit voice recorder (CVR) or a flight data recorder (FDR), nor was it required to.[3]: 12

Crew and passengers

[edit]The DHC-6 was carrying 22 occupants, 2 flight crew members and 20 passengers, one of whom was an infant. The captain of the flight was 29-year-old Scott Alan Klopfenstein, who had 7,340 flight hours, 3,904 of which were on the DHC-6. The first officer of the flight was 34-year-old Gary Coleman, who had 3,816 flight hours, 320 of which were on the DHC-6.[3][2][5] Three of the passengers on the flight were employees of the United States Forest Service (USFS).[6]

Flight

[edit]Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217 was intended to depart Steamboat Springs Airport at 16:45[a], but was delayed because the inbound flight from Stapleton International Airport, Flight 216, arrived at 18:21 due to a delayed departure from Stapleton and strong headwinds en route. The crew reported that they encountered heavy rime icing during the descent into Steamboat Springs but the flight was otherwise smooth and without turbulence. Both the captain and first officer had to remove ¾ inches (1.9 cm) of ice from the aircraft after landing.[3]

Captain Klopfenstein planned a flight plan using instrument flight rules (IFR) between Steamboat Springs Airport and the Gill VOR along the V101 airway at 17,000 ft (5,200 m)[b] and from Gill, proceed with visual flight rules (VFR) to Denver.[3]

Accident

[edit]

Flight 217 departed from Steamboat Springs at 18:55, two hours and ten minutes behind schedule, and was cleared to climb to its assigned altitude of 17,000 ft (5,200 m). First Officer Coleman, who was in command of the flight, flew the aircraft following the published departure for the airport, reversed course at 10,000 ft (3,000 m), crossed the non-directional beacon (NDB) over Steamboat Springs Airport at 12,000 ft (3,700 m), and intercepted the V101 airway flying east.[3] The aircraft encountered minor freezing precipitation and entered a cloud bank as it was climbing over Buffalo Pass. The Twin Otter encountered severe icing conditions on the aircraft's propellers and windshield, but the aircraft's deicing systems was able to remove the ice. The flight was able to climb up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m), but neither the first officer nor the captain was able to make the aircraft climb to a higher altitude at the normal engine power settings. Due the aircraft's inability to reach an altitude above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before the Kater intersection, a point at the intersection of two radials, the captain elected to return to Steamboat Springs at 19:14, without informing the passengers.[3][6]

Flight 217 transmitted to Denver Center, the air traffic control (ATC) center in contact with the flight, that they would have to return to Steamboat Springs. Denver Center soon called the station agent at Steamboat Springs, telling him that Flight 217 was returning to airport. Later, the flight reported that they had encountered heavy icing conditions and that they recommended that no other flights should attempt to fly in the area.[3][7] The flight turned back west and soon crossed the 335° radial from the Kremmling VOR. At this time, the flight encountered its first severe icing conditions while returning for approximately 12 seconds. The flight descended uncommanded from 13,000 ft (4,000 m) to 11,600 ft (3,500 m) before Captain Klopfenstein was able to extend the flaps on the wings. At this time, the flight had an indicated airspeed of 90–100 kn (100–120 mph) and roughly 1.5–2 in (3.8–5.1 cm) thick ice.[3] At 19:39, the aircraft transmitted, "...want you to be aware that we're having a little problem here maintaining altitude and proceeding direct Steamboat beacon." Denver controllers offered their assistance, but the flight replied with, "not now," which would be the final transmission from the flight.[7] Shortly after this transmission, the aircraft encountered another area of severe icing. This resulted in the Twin Otter to beginning another uncontrolled descent at a rate of 800–1,000 fpm, even with the engines at maximum climb power. Shortly before impact, the first officer advanced the engine levers to maximum takeoff go-around power, selected fully extended flaps, and told the captain to bank right.[3] However, the aircraft's right wingtip impacted a high-voltage electrical tower, causing a short circuit and a power outage in the nearby town of Walden. At 19:45, Flight 217 impacted the ground near another electrical tower, coming to rest on its right side, without its left wing and with a severely damaged right wing.[3][5][6] The wreckage distributed on a 200 ft (61 m) was on a 1-6° slope, partially buried in snow at an elevation of 10,530 ft (3,210 m). The aircraft remained mostly intact, although the fuselage around the wing fittings had openings in them.[3]

Passenger efforts and rescue

[edit]All 22 people on board survived the initial impact. 14 passengers and both crew members were seriously injured, with the majority of them suffering fractured spinal cords, lacerations, fractured ribs, and frostbite. The remaining six passengers, including the eight-month-old infant, were only minorly injured, suffering similar injuries to the severely injured passengers.[3][8]

Despite the aircraft being severely damaged in the crash, the cabin lights remained on for 4 to 5 hours after the crash, which was ruled to be a significant reason for passenger survival.[3][7] One of the slightly injured passengers was a 20-year-old male who had extensive winter survival training. He and another male passenger were able to exit the cabin and obtain warm clothing, which was distributed to the most injured passengers. Despite the efforts of the least injured passengers, a 26-year-old female, one of the USFS employees on the flight, died of her injuries approximately 4 hours after the crash.[3]

In the cockpit, both Captain Klopfenstein and First Officer Coleman were severely injured and were trapped in their seats in the snow. The same passenger who had winter survival training attempted to remove the snow around the first officer but was unsuccessful due to the violent winds. He and another passenger built a shelter around the first officer with suitcases.[3][6]

During the crash, one of the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) on the aircraft activated.[c]. A United States Air Force Lockheed C-130 Hercules received a radio signal from the activated ELT, but without special direction-finding equipment, the crew misidentified the crash site 12 miles (19 km) east-northeast of the actual crash site.[3][7] Rescuers from the Colorado Civil Air Patrol, the Routt County Sheriff Office, and personnel from the Steamboat Springs Airport were notified about the missing aircraft in the hours after the crash, and met together in Walden. Between 19:45 on December 4, when the aircraft crashed, and 06:00 the next day, rescue teams used Sno-cats and snowmobiles to find the missing aircraft.[3][5][6] The efforts were hampered by a blizzard that produced over 8 ft (2.4 m) of snow, brought 40 mph (64 km/h) winds, and temperatures −50 °F (−46 °C).[2] One of the rescuers apart of the Civil Air Patrol team used a portable ELT receiver and was able to track down the site of the crash, further guided by the area where the downed powerlines were.[3][5] They found the crash site at 06:00 on December 5, although emergency medical services arrived an hour and 45 minutes later. The passengers and crew members were taken to hospitals in Steamboat Springs and in Kremmling, where all would recover except the captain, who would die 70 hours after the accident.[3] The rescue is considered one of the most successful in the Civil Air Patrol's history.[5]

Investigation

[edit]The investigation was conducted by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), with representatives from the Federal Aviation Administration, Rocky Mountain Airways, de Havilland Canada, the Air Line Pilots Association, and Pratt and Whitney.[3]

Effects of icing

[edit]

In a post-accident interview, First Officer Coleman told the NTSB that the aircraft's deicing and anti-icing systems were functioning properly during the flight. Evidence in the wreckage supported this, with the deicing boots being clear of ice. However, due to the conditions the flight flew in, the NTSB had to consider ice as a possible factor in the accident.[3] Studies in the 1950s showed that the presence of ice on the wings significantly decreases flight performance. In certain weather conditions and with a high angle of attack, airfoil drag can increase by 50–100% and the lift coefficient can decrease by 5–13%.[9] The topography of the area influenced the formation of icing conditions. The area, situated near and over a mountain range, allowed for atmospheric inversion, which led to the formation of freezing rain, snow, and ice pellets. Additionally, two pilots who flew in the area on the night of the crash reported to the NTSB that they encountered moderate icing conditions. The NTSB concluded that the presence of ice on the wings likely contributed to the degraded performance observed on Flight 217. Evidence indicated that ice built up on the unprotected frontal surfaces of either wing, including residual ice on the deicing boots themselves.[3]

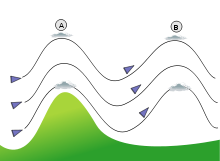

Effects of mountain waves

[edit]

The route that the aircraft went over the Park Range, a mountain range between the North Park basin and Elk River, where Steamboat Springs is located.[10] The geography of the area, combined with the meteorological conditions at the time of the crash, was concluded to be conductive to the formation of a mountain wave.[3] A mountain wave is a disruption in the horizontal wind flow on the lee side of a terrain feature causing the disruption, usually a mountain. Mountain waves are usually associated with the presence of high surface winds.[11][3] In the case of Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217, a stable air mass and high winds over the Park Range resulted in the formation of a mountain wave over the mountain range. The North Park basin also helped the development of the mountain wave, with the lower elevation of the plain resulting in stronger winds in the mountain wave. NTSB simulations showed that downdrafts associated with the mountain wave had accelerations of over 500 fpm. Despite the presence of one or multiple mountain waves over the flight's planned route, neither the SIGMET nor the AIRMET issued to the crew mentioned mountain waves.[3]

Certification data the NTSB acquired showed that under the icing conditions the flight encountered, the crew should have been able to maintain an altitude of 19,500 ft (5,900 m). But since the aircraft was not able to climb above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before its diversion, the NTSB concluded that the downdrafts associated with the mountain waves in the area combined with the icing conditions on the flight was beyond the aircraft's ability to maintain flight.[3]

Captain's decision to conduct the flight

[edit]The NTSB highlighted Captain Klopfenstein's decision to conduct the flight and the flight's attempted return to Steamboat Springs. The captain's decision to return to his origin airport was prompted by the aircraft's inability to climb above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before the Kater Intersection.[3][2] Due to terrain that existed east of the Kater Intersection, aircraft had to climb to 16,000 ft (4,900 m) by Kater. The icing conditions, downdrafts from mountain waves, and a tailwind above 9,000 ft (2,700 m) resulted in the aircraft's inability to climb. The NTSB speculated that if the captain did not know the strength of the tailwind and downdrafts, he might have believed that icing was the main cause for the inability to climb, and that might have influenced his decision to return. However, they concluded that the captain's decision to return was reasonable based on the information available at the time.[3]

Captain Klopfenstein's decision to depart Steamboat Springs in the first place was ruled as an even larger factor in the accident. The captain was aware of the severe weather conditions that he would later experience on the flight. Earlier on December 4, he and First Officer Coleman attempted to fly Flight 212 to Steamboat Springs via Granby. Due to strong winds en route, the flight was unable to climb high enough, and the flight had to return to Denver. Later, on Flight 216, they encountered strong headwinds and heavy icing on the descent into Steamboat Springs.[3]

Company procedure at Rocky Mountain Airways prohibited flight into "known or forecast heavy icing conditions...unless the captain has good reason to believe that the weather conditions as forecast will not be encountered due to change or later observed conditions." The NTSB stated that the captain, who had considerable experience in mountain flying conditions, believed that the calm conditions on Flight 216 would allow for a smooth flight to Denver. He was likely unaware of the strong winds in the area as during Flight 216's descent, the severe icing likely masked the simultaneous performance degradation the winds brought. Additionally, the weather conditions at Steamboat Springs were calm and did not correlate with mountain wave conditions, and the meteorological information provided to him made no mention of such conditions.[3]

In regard to Captain's Klopfenstein's decision to fly, the NTSB concluded that he was not aware of the presence of the mountain wave(s) en route. Evidence showed that signals that showed mountain wave conditions were obscured by other weather conditions that were already on the captain's mind. This led to a false attitude of safety, where the captain believed that he could fly to Denver even if it was against company guidance.[3]

Final report

[edit]In their final report, the NTSB concluded the probable cause of the accident was:

Severe icing and strong downdrafts associated with a mountain wave which combined to exceed the aircraft's capability to maintain flight. Contributing to the accident was the captain's decision to fly into probable icing conditions that exceeded the conditions authorized by company directive.[12][3]: 30

They recommended that crew members who fly for commuter airlines in mountainous areas should have survival training, and mandatory installation for shoulder harnesses in flight crew seats on FAR part 135 flights. The latter recommendation was issued as the lack of harnesses contributed to the captains' fatal injuries.[3]

Aftermath

[edit]The departure procedure for Steamboat Springs was changed to allow aircraft to gain more altitude flying westward before turning east over the mountains.[8]

In 2009, a memorial to the crash was unveiled at the Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum by First Officer Coleman, many of the surviving 19 passengers, and several of the rescuers.[5]

See also

[edit]- Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 (1972) – Crashed in the Andes, 72-day survival

- Trans-Colorado Airlines Flight 2286 (1988) – Crashed in snowy conditions in Southern Colorado

- Varig Flight 254 (1989) – Forced landing in the Amazon rainforest, 4-day survival

- Iran Aseman Airlines Flight 3704 (2018) – Crashed into Mount Dena in mountain wave conditions

Notes

[edit]- ^ All times are listed in Mountain Standard Time; UTC-7

- ^ All altitudes are in reference to height above mean sea level

- ^ The first officer carried a portable ELT along with the one installed on the aircraft

References

[edit]- ^ Heffel, Nathan (December 19, 2017). "Miracle on Buffalo Pass Remembered Nearly 40 Years After Plane Crash". Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shapiro, Gary (September 30, 2018). "Hope on Buffalo Pass: The incredible rescue of flight 217". 9News. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Aircraft Accident Report: Rocky Mountain Airways, Inc. deHavilland DHC-6 Twin Otter, N25RM, near Steamboat Springs, Colorado, December 4, 1978 (PDF) (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. May 3, 1979. NTSB-AAR-79-6. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ "Crash of a De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter in Steamboat Springs: 2 killed". Bureau of Aircraft Accident Archives. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Pankratz, Howard (March 5, 2009). "1978 plane crash recalled in new exhibit". The Denver Post. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Hohl, Frances. "Buff Pass plane crash survivor, rescuer share 'miracle' stories". Steamboat Pilot. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Katz, Peter (January 7, 2019). "After the Accident: Twin Otter Crash In The Rockies From 40 Years Ago". planeandpilotmag.com.

- ^ a b Terell, Blythe (June 8, 2008). "Infant who survived 1978 plane crash on Buffalo Pass now soars above Yampa Valley himself". Steamboat Pilot. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ Bowden, Dean T. (February 1, 1956). "Effect of Pneumatic De-icers and Ice Formations on Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Airfoil" (PDF). National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Park Range". peakbagger.com. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Mountain Waves". SkyBrary. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "Accident de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 N25RM, Monday 4 December 1978". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- 1978 in Colorado

- Accidents and incidents involving the de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter

- Airliner accidents and incidents in Colorado

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States in 1978

- December 1978 events in the United States

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by weather

- Airliner accidents and incidents caused by ice