SMS Schwaben

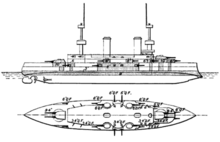

SMS Schwaben's sister ship Wittelsbach

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Schwaben |

| Namesake | Duchy of Swabia |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | 15 September 1900 |

| Launched | 19 August 1901 |

| Christened | Queen Charlotte of Württemberg |

| Commissioned | 13 April 1904 |

| Stricken | 8 March 1921 |

| Fate | Scrapped in 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Wittelsbach-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 126.8 m (416 ft) |

| Beam | 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi); 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

SMS Schwaben ("His Majesty's Ship Swabia")[a] was the fourth ship of the Wittelsbach class of pre-dreadnought battleships of the German Imperial Navy. Schwaben was built at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven. She was laid down in 1900, and completed in April 1904. Her sister ships were Wittelsbach, Zähringen, Wettin and Mecklenburg; they were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898, championed by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. Schwaben was armed with a main battery of four 24-centimeter (9.4 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).

Schwaben spent most of her career as a gunnery training ship from 1904 to 1914, though she frequently participated in the large scale fleet exercises during this period. After the start of World War I in August 1914, the ship was mobilized with her sisters as IV Battle Squadron. She saw limited duty in the North Sea as a guard ship and in the Baltic Sea against Russian forces. The threat from British submarines forced the ship to withdraw from the Baltic in 1916. For the remainder of the war, Schwaben served as an engineering training ship for navy cadets. She was retained by the Reichsmarine after the war and reactivated from 1919 until June 1920, serving as a depot ship for F-type minesweepers in the Baltic. The ship was stricken from the navy list in March 1921 and sold for scrapping in that year.

Description

[edit]

After the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) ordered the four Brandenburg-class battleships in 1889, a combination of budgetary constraints, opposition in the Reichstag (Imperial Diet), and a lack of a coherent fleet plan delayed the acquisition of further battleships. The Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Navy Office), Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Friedrich von Hollmann struggled throughout the early and mid-1890s to secure parliamentary approval for the first three Kaiser Friedrich III-class battleships. In June 1897, Hollmann was replaced by Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz, who quickly proposed and secured approval for the first Naval Law in early 1898. The law authorized the last two ships of the class, as well as the five ships of the Wittelsbach class,[1] the first class of battleship built under Tirpitz's tenure. The Wittelsbachs were broadly similar to the Kaiser Friedrichs, carrying the same armament but with a more comprehensive armor layout.[2][3]

Schwaben was 126.8 m (416 ft) long overall and had a beam of 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) and a draft of 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) forward. She displaced 11,774 t (11,588 long tons) as designed and up to 12,798 t (12,596 long tons) at full load. The ship was powered by three 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engines that drove three screws. Steam was provided by six water-tube and six cylindrical coal-fired boilers. Schwaben's powerplant was rated at 14,000 metric horsepower (13,808 ihp; 10,297 kW), which generated a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). The ship had a cruising radius of 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). She had a crew of 30 officers and 650 enlisted men.[4]

Schwaben's armament consisted of a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) SK L/40 guns in twin gun turrets,[b] one fore and one aft of the central superstructure. Her secondary armament consisted of eighteen 15 cm (5.9 inch) SK L/40 and twelve 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns. The armament system was rounded out with six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, all submerged in the hull; one was in the bow, one in the stern, and the other four were on the broadside. Her armored belt was 100 to 225 millimeters (3.9 to 8.9 in) thick in the central citadel that protected her magazines and machinery spaces, and the deck was 50 mm (2 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 250 mm (9.8 in) of armor plating.[6]

Service history

[edit]Construction – 1905

[edit]Schwaben's keel was laid 15 September 1900, at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven, under construction number 27. She was ordered under the contract name "G", as a new unit for the fleet.[6] Schwaben was launched on 19 August 1901; during the launching ceremony, King Wilhelm II of Württemberg gave a speech and his wife Queen Charlotte of Württemberg christened the ship.[7] She was commissioned on 13 April 1904, the last ship of her class to enter active service.[8] The ship's cost totaled 21,678,000 marks[6]

There was a dispute over where Schwaben should be assigned after her commissioning in April 1904. Admiral Hans von Koester, the fleet commander, wanted the ship to be assigned to the active duty squadron, but Tirpitz wanted to use the new battleship as a training vessel, since the Training Squadron only possessed cruisers and obsolescent ships. Tirpitz won the debate, and so Schwaben was to replace the ancient ironclad frigate Friedrich Carl in the Training Squadron. There, she was to serve as a torpedo training ship. On 18 May, Schwaben departed Wilhelmshaven and passed through the Skagerrak to the Baltic Sea, arriving in Kiel on 22 May.[7]

While on sea trials, she struck an uncharted shoal off the northern tip of the island of Fehmarn. The impact damaged a 30-meter (98 ft) length of the ship's hull and holed it in several places. After repairs were completed, she resumed her trials, which lasted until the end of 1904. The trials were interrupted by the annual autumn maneuvers, during which Schwaben joined the active fleet in the North Sea. On 11 January 1905, she was formally assigned to the Training Squadron, but as an artillery training ship to replace the old vessel Mars.[7] The ship was based in Sonderburg in the Baltic, along with the armored cruisers Prinz Heinrich and Prinz Adalbert, and several other training ships.[9] She began an annual routine of gunnery training in the western Baltic that was interrupted only by yearly gunnery drills with the entire High Seas Fleet in October. During these fleet exercises, Schwaben was supported by the tender Ulan. Schwaben also went into drydock from the end of October to the middle of December every year for periodic maintenance.[7]

1906–1914

[edit]Schwaben participated in exercises in the Swinemünde Bay in April and May 1906, and the annual fleet gunnery drills took place off Helgoland in August. Her annual overhaul was completed early, in November. In March 1907, Schwaben participated in gunnery training with the fleet. She joined the flagship of the Reserve Squadron, the coastal defense ship Frithjof, for maneuvers off the coast of Farther Pomerania in July. The following month, Schwaben served as the flagship of VAdm Hugo Zeye for a training squadron during the fleet maneuvers in the North Sea. Directly after the conclusion of the fleet maneuvers in mid-September, Schwaben participated in fleet gunnery drills off Helgoland. The year was concluded with an overhaul in the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven.[10]

In 1908, the training ships based in the Baltic were placed under the command of Rear Admiral Hugo von Pohl,[11] who would go on to command the High Seas Fleet in 1915 during World War I.[12] That year followed the same pattern as the previous year, but Schwaben did not participate in the autumn fleet maneuvers. She instead remained at Sonderburg and Alsen during the exercises. In 1909, after the autumn maneuvers, Schwaben was assigned as the flagship of the Reserve Fleet, again under the command of Admiral Zeye. During her yearly overhaul at the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven, her guns were fitted with new motors produced in Germany to test their reliability over foreign-manufactured motors. The tests proved to be successful. While steaming in the Flensburg Firth on 10–12 December, she had to assist the training ship Württemberg in heavy fog.[10]

In 1910, after the normal training routine in the first half of the year, Schwaben was assigned to III Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet for the autumn maneuvers, which lasted from 19 August to 11 September. She served in this role to replace the battleships Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and Weissenburg, which had been sold to the Ottoman Empire just before the start of the maneuvers. On 14 October, she joined up with the battleship Elsass and steamed through the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal to Kiel for her yearly overhaul at the Imperial Dockyard there. These repairs lasted until 4 January 1911. Schwaben served in III Battle Squadron during the autumn maneuvers again in 1911.[10] By 1911, the eight Nassau and Helgoland classes of dreadnought battleships had entered service;[13] these ships were assigned to I Battle Squadron, which displaced the newer pre-dreadnoughts of the Deutschland and Braunschweig classes to II and III Battle Squadrons.[14] As a result, Schwaben was decommissioned in Wilhelmshaven on 30 December 1911 and assigned to the Reserve Division in the North Sea. She was placed back in service briefly from 9 to 12 May 1912 to move to Kiel. Schwaben returned to service again to participate in the autumn maneuvers from 14 August to 28 September, as the flagship of then-KAdm Maximilian von Spee.[10]

World War I

[edit]

After the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Schwaben and the rest of her class were mobilized to serve in IV Battle Squadron, under the command of Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt.[15] After it reached full combat readiness, the Squadron was employed both as a defense force in the German Bight—usually stationed in the mouth of the Elbe—and for operations in the Baltic.[10] Starting on 3 September, IV Squadron, assisted by the armored cruiser Blücher, conducted a sweep into the Baltic. The operation lasted until 9 September and failed to bring Russian naval units to battle.[16] In May 1915, IV Squadron, including Schwaben, was transferred to support the German Army in the Baltic Sea area.[17] Schwaben and her sisters were then based in Kiel.[18] During this period, she served as the flagship of the second command admiral of the Squadron, KAdm Alberts.[10]

On 6 May, the IV Squadron ships were tasked with providing support to the assault on Libau. Schwaben and the other ships stood off Gotland to intercept any Russian cruisers that might try to intervene in the landings, which the Russians did not attempt. On 10 May, after the invasion force had entered Libau, the British submarines HMS E1 and HMS E9 spotted IV Squadron, but were too far away to make an attack.[18] The increasingly active British submarines forced the Germans to employ more destroyers to protect the capital ships. As a result, Schwaben and her sisters were not included in the German fleet that assaulted the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, due to the scarcity of escorts.[19] On 29 August, Kapitän zur See (Captain at Sea) Walter Engelhardt replaced Alberts aboard Schwaben. She was then used as a guard ship in Libau, starting on 24 September. On 10–11 November, Schwaben, her sisters Wittelsbach and Wettin, and Prinz Heinrich left Libau, bound for Kiel.[10]

By late 1915, the increasing threat from British submarines in the Baltic convinced the German navy to withdraw the elderly Wittelsbach-class ships from active service.[20] On 20 November Schwaben steamed to Wilhelmshaven, where she replaced Kaiser Karl der Grosse as a training ship for engineers, a role she held for the remainder of the war.[8][21] After the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June, in which Schwaben did not take part, Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper, the commander of the German battlecruiser squadron,[22] sent his four surviving battlecruisers to dock for repairs. Hipper made Schwaben, which was stationed in Wilhelmshaven, his temporary command ship while his force was being repaired.[23] In 1916, Schwaben was partially disarmed; the four 24 cm guns were removed, her battery of 15 cm guns was reduced to six weapons, and only four 8.8 cm guns were left aboard.[24]

Postwar service

[edit]The ship was briefly retained by the Reichsmarine after the war, and was reactivated for service on 1 August 1919.[24] According to Articles 182 and 193 of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was obliged to keep sufficient vessels in commission to sweep mines from large areas in the North and Baltic Seas.[25] Schwaben was therefore converted into a depot ship for F-type minesweepers to assist in meeting Germany's treaty obligations,[26] which entailed removal of her remaining weaponry and construction of platforms to hold the minesweepers. She was assigned to the 6th Baltic Minesweeping Half-Flotilla, though this service did not last long, as the minesweeping work was completed by 19 June 1920. The old battleship was stricken from the naval register on 8 March 1921. She was sold for 3,090,000 marks and broken up for scrap that year in Kiel-Nordmole.[8][24]

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 calibers, meaning that the gun is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.[5]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 180–189, 216–218, 221–225.

- ^ Herwig, p. 43.

- ^ Lyon, p. 248.

- ^ Gröner, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 16.

- ^ a b c d Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 140.

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 17.

- ^ "Germany", p. 1049.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 141.

- ^ "The German Fleet", p. 10.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 43.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Staff, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Scheer, p. 15.

- ^ Halpern, p. 185.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Halpern, p. 192.

- ^ Halpern, p. 197.

- ^ Herwig, p. 168.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 287.

- ^ Raeder, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 142.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles Section II: Naval Clauses, Articles 182 and 193.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 141.

References

[edit]- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- "Germany". Proceedings. 37. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute: 1044–1050. 1911. ISSN 0041-798X.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 7. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0267-1.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Raeder, Erich (1960). My Life. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 883168.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918 (1). Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- "The German Fleet". The Navy. Washington D.C.: Navy Publishing Co.: 10–11 1908. OCLC 7550453.

Further reading

[edit]- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2001). Die Panzer- und Linienschiffe der Brandenburg-, Kaiser Friedrich III-, Wittlesbach-, Braunschweig- und Deutschland-Klasse [The Armored and Battleships of the Brandenburg, Kaiser Friedrich III, Wittelsbach, Braunschweig, and Deutschland Classes] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-6211-8.