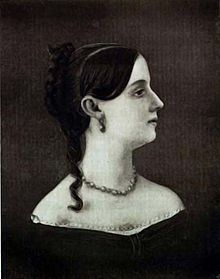

Sara Agnes Rice Pryor

Sara Agnes Rice Pryor | |

|---|---|

Sara Agnes Rice Pryor | |

| Born | February 19, 1830 |

| Died | February 15, 1912 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse | Roger Atkinson Pryor |

| Children | Maria Gordon Pryor Theodorick Bland Pryor Roger Atkinson Pryor Mary Blair Pryor William Rice Pryor Lucy Atkinson Pryor Francesca (Fanny) Theodora Bland Pryor |

| Parent(s) | Samuel Blair Rice Lucinda Walton Leftwich |

Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, born Sara Agnes Rice (February 19, 1830 – February 15, 1912), was an American writer and community activist in New York City. Born and reared in Virginia, she moved north after the American Civil War with her husband and family to rebuild their life. He was a former politician and Confederate general; together, they became influential in New York society, which included numerous "Confederate carpetbaggers" after the war. After settling in New York, she and her husband renounced the Confederacy.

Pryor co-founded a home for women and children in Brooklyn, New York. Pryor helped found heritage organizations, including Preservation of the Virginia Antiquities, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the National Mary Washington Memorial Association, and the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America. She was active in fundraising to support their goals. She was a central figure in fundraising for a yellow fever outbreak to benefit children in Jacksonville, Florida.[1]

In the early 1900s, Pryor published two histories, two memoirs of the Civil War era, and novels with the Macmillan Company. The United Daughters of the Confederacy recommended her first memoir, which encouraged southern women writers to defend Southern chivalry. Her memoirs have been sources for historians on the life of her society during and after the war.

Early life, lineage and education

[edit]Sara Agnes Rice was born in Halifax County, Virginia, to Samuel Blair Rice,[2] a Baptist preacher, and his second wife, Lucinda Walton Leftwich (1807–1855); they had more than ten children together. At about the age of three, Sara was effectively adopted by her childless aunt, Mary Blair Hargrave, and her husband, Dr. Samuel Pleasants Hargrave, and lived mostly with this couple in Hanover, Virginia.[3] The aunt and uncle were enslavers.[4] When Sara was about eight, the Hargraves moved to Charlottesville to seek a better education for her.[5]

On her father's side, Sara was a granddaughter of William Rice of "Greenwood", Charlotte County, Virginia, and his wife Mary Bacon Crenshaw. She was a great-granddaughter of David Rice, a Presbyterian minister in Kentucky, and his wife, Mary Blair. Sara named one of her daughters "Mary Blair" in keeping with her grandfather William's wish to honor the original Mary Blair, his mother.[6] David Rice acted as clergyman and orator to the Hanover militia in 1775. He was a member of the 1792 convention that framed the first Constitution of Kentucky.

On her mother's side, she was a granddaughter of Rev. William Leftwich and Frances Otey and a great-granddaughter of Col. John Otey, of Bedford, Virginia, and his wife Mary Hopkins. Col. John Otey served as colonel and captain of a battalion of riflemen. Also a descendant of Col. William Leftwich, Samuel Blair, and Maj. Gen. Joel Leftwich.[7]

Marriage and family

[edit]On November 8, 1848, Sara Agnes Rice married Roger Atkinson Pryor of a Virginia Tidewater family. A journalist, Roger became a politician. Roger was elected to both the US Congress and the Confederate Congress after Virginia's secession. Although the Pryors did not enslave people, each had grown up in enslaving families. Roger advocated for slavery with fiery speeches before the American Civil War. After the war, Roger publicly expressed his regret for supporting the Confederacy.

Sara and Roger A. Pryor had seven children, the last born after the war.[8]

- Maria Gordon Pryor (called Gordon) (1850–1928); married her cousin Henry Crenshaw Rice (1842–1916). Their daughter Mary Blair published several books under the pen name Blair Niles.[9]

- Theodorick Bland Pryor (1851–1871), died at age 20, likely a suicide, as he had been suffering from depression.[10] Admitted to Princeton College at a young age, he was its first mathematical fellow; he also studied at Cambridge, and had been studying law.[10] He was buried in Princeton Cemetery.

- Roger Atkinson Pryor; became a lawyer in New York.[11]

- Mary Blair Pryor; married Francis Thomas Walker,[11] she had daughter Mary Blair Walker Zimmer.[1][5] Buried in Princeton Cemetery.

- William Rice Pryor (b. c.1860 – 1900[12]); became a physician and surgeon in New York and died young.[11] He was buried in Princeton Cemetery.

- Lucy Atkinson Pryor; married A. Page Brown, an architect. In 1889, they moved to San Francisco, California.

- Francesca (Fanny) Theodora Bland Pryor (b. 31 December 1868), Petersburg, Virginia; married William de Leftwich Dodge, a painter. They lived in Paris,[11] followed by New York City.

American Civil War

[edit]When Roger joined the Confederate States Army as a commissioned officer, Pryor traveled with his company and worked as a nurse.[2] Their children were likely cared for by Roger's family living in Petersburg. After Roger resigned his commission to join Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry, Pryor returned to Petersburg to keep their family together.[2]

New York City

[edit]After the war, Roger moved to New York, where he read law and started a new law practice. Pryor and the children joined him, moving to Brooklyn Heights in 1868.[13] Pryor's second memoir describes their struggle through ten years of relative poverty (Pryor always had a domestic servant, first a former slave from Virginia, who returned to the Southern United States, and then an Irish woman).[13] Pryor sewed her children's clothes, enrolled the younger girls at the Packer School, borrowed money from a family friend using Roger's war silver as collateral, and helped Roger with his legal studies.[13]

The couple became prominent among some influential southerners in New York, who were known as "Confederate carpetbaggers."[14]

Civic organizing

[edit]Pryor became active in the social life of New York City in the late nineteenth century. Pryor and her friends noted the struggle of the thousands of women and children immigrating to the city. With other women in Brooklyn Heights, Pryor raised money to create a home for women and children in need. Pryor's petition to the state legislature granted the group $10,000 toward purchasing a building in Brooklyn. After fundraising an additional $20,000, the women started the home in the 1870s.[13]

In her memoir, Pryor noted that following the 1889 United States Centennial celebration in New York, interest greatly increased in historical items, buildings, and collections. Pryor helped found and develop the following organizations, at a time when fraternal, civic, and lineage societies were forming quickly:

- Preservation of the Virginia Antiquities (since 2009 named Preservation Virginia), which came to own historic Jamestown among other properties;

- Mary Washington Memorial Association, which raised funds to commission a memorial for the gravesite of the first president's mother;

- Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR); and

- National Society of the Colonial Dames of America.

She organized a New York DAR chapter. Among her fundraising activities, Pryor wrote that she "managed a great ball at the White Sulphur Springs to help build a monument over Mary Washington's grave."[15]

Literary career

[edit]Pryor also became a productive writer, having kept journals for years and using them as a basis for her two memoirs published in the early twentieth century.[16] She joined other Southern women at the time who began to publish work reflecting their own experiences and "contributed to the public discourse about the war."[16] Nearly a dozen memoirs by Southern women were published around the turn of the century.[17] Pryor's status as the wife of a Confederate officer and politician gave her legitimacy. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) encouraged southern women to write about their experiences and publish their work, which enlarged their cultural power.[16] In her Reminiscences of Peace and War (1904), Pryor wrote about antebellum society, but she also defended the Confederacy, as did fellow writers Virginia Clay-Clopton and Louise Wigfall Wright. The UDC recommended the works of these three for serious study by other women.[16]

Like her husband in his speeches[18] Pryor argued the war had nothing to do with slavery, suggesting that the average Confederate combatant fought to resist an invasion by the North. After noting that most Confederates were not enslavers, she wrote, "His quarrel was a sectional one and he fought for his section."[16]

In addition, Pryor wrote two histories and several novels, all published by The Macmillan Company in the early 1900s. Perhaps because of her status in New York, she had continued success in getting her books published at a time when Southern women writers had difficulty achieving this.[16] Her memoirs have been important sources for historians.[2] In the late 20th century, writer John C. Waugh drew extensively from her works for his joint biography of the Pryors: Surviving the Confederacy: Rebellion, Ruin, and Recovery: Roger and Sara Pryor during the Civil War (2002), which was also a social history of their circle.

After her death, Sara Agnes Rice Pryor was buried at Princeton Cemetery, near her sons Theodorick and William. Her husband and their daughter, Mary Blair (Pryor) Walker, were also buried there after their deaths.[19]

Pryor's prominence in the Washington political scene is documented in Capital Dames: The Civil War and the Women of Washington (2015), by Cokie Roberts.[20] Pryor's influence on naming female descendants after her ancestor Mary Blair is documented in Mary Blair Destiny (2019), by 3xgreat-granddaughter, Erin L. Richman.[19]

Works

[edit]- The Mother of Washington and her Times, New York: Macmillan Company, 1903.

- Reminiscences of Peace and War, Macmillan Company, 1905 (revised edition; first published by Grosset & Dunlap in 1904).

- The Birth of the Nation: Jamestown, 1607, Macmillan Company, 1907.

- My Day: Reminiscences of a Long Life, New York: Macmillan, 1909, carried at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina

- The Colonel's Story, New York: Macmillan, 1911, novel.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Erin L. Richman, Mary Blair Destiny, Two Goddesses Publishing, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Harris Henderson, "Summary", at Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, My Day (1909), at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed 24 April 2012

- ^ Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, "Dedication to Mary Blair Hargrave", in The Colonel's Story, New York, Macmillan, 1911

- ^ Sara Agnes Rice Pryor, My Day: Reminiscences of a Long Life, Macmillan Company, 1909, at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b Richman, Erin Mary Blair Destiny, Two Goddesses Publishing, pages 41-42 ISBN 978-1-7330180-0-5.

- ^ Richman, Erin. Mary Blair Destiny, Two Goddesses Publishing ISBN 978-1-7330180-0-5.

- ^ * Lineage Book of the Charter Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution. National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. 1891.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ James pg. 103

- ^ Erin L. Richman (2019), Mary Blair Destiny, Two Goddesses Publishing.

- ^ a b Thomas Danly Suplee, The Life of Theodorick Bland Pryor: First Mathematical-Fellow of Princeton College, Bacon, 1879

- ^ a b c d "THE PRYOR FAMILY" Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 7, Number 1, July 1899, pp. 75–79, carried at Tennessee Pryor's website, accessed 13 April 2012

- ^ Pryor (1909), My Day, pp. 347–348, accessed 13 April 2012

- ^ a b c d Pryor (1909), My Day, pp. 336–339, accessed 23 April 2012

- ^ David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001, p. 90

- ^ Pryor (1909), My Day, p. 420, carried at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina, accessed 13 April 2012. Note: White Sulphur Springs was a traditional resort in the mountains of West Virginia for southern planters.

- ^ a b c d e f Sarah E. Gardner, Blood And Irony: Southern White Women's Narratives of the Civil War, 1861–1937, University of North Carolina Press, 2006, pp. 128–130

- ^ Gardner (2006), Blood and Irony, p. 130

- ^ Blight (2001), Race and Reunion, pp. 90–91

- ^ a b Erin L. Richman (2019), Mary Blair Destiny, Two Goddesses Publishing

- ^ Cokie Roberts (2015), Capital Dames: The Civil War and the Women of Washington 1848-1868, Harper

Further reading

[edit]- Garraty, John A. and Mark C. Carnes, eds., American National Biography, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- "Justice Pryor Is 90 Years Old", New York Times, 20 July 1918

- Roberts, Cokie, "Capital Dames: The Civil War and the Women of Washington 1848-1868," Harper, 2015.

- Waugh, John C. Surviving the Confederacy: Rebellion, Ruin, and Recovery: Roger and Sara Pryor during the Civil War (2002)

External links

[edit]- People from Halifax County, Virginia

- 1830 births

- 1912 deaths

- Novelists from New York City

- People of Virginia in the American Civil War

- 20th-century American women writers

- Novelists from Virginia

- Women in the American Civil War

- Activists from New York City

- 20th-century American novelists

- People from Hanover, Virginia

- Burials at Princeton Cemetery

- Daughters of the American Revolution people

- Members of the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America