Siege of Batavia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2020) |

| Siege of Batavia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

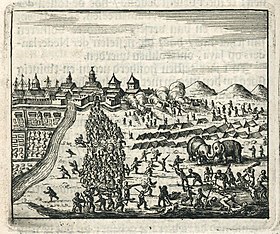

Siege of Batavia by Sultan Agung in 1628 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000 (first siege) 14,000 (second siege) |

500–800 including foreign mercenaries from Japan, China, India, Africa, the Moluccas, Celebes, and Java (first siege) ? (second siege) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| More than 5,000 | Small amount | ||||||

The siege of Batavia was a military campaign led by Sultan Agung of Mataram to capture the Dutch port-settlement of Batavia in Java. The first attempt was launched in 1628, and the second in 1629; both were unsuccessful.[1]

Prelude

[edit]In the Indonesian Archipelago the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) first established their base of operation in Amboina. To expand their trading network, the Dutch asked for the permission of the Sultanate of Mataram, then the rising power in Java, to build lojis (trading posts, most consisting of a fort and warehouses) along Java's northern coast. The second ruler of Mataram, Raden Mas Jolang, allowed one such settlement to be built in Jepara in 1613, perhaps in hope that the company will be a powerful ally against his most powerful enemy, the city state of Surabaya.

After the VOC under their most renowned governor general Jan Pieterszoon Coen had wrested the port of Jacatra (Jayakarta) from Sultanate of Banten in 1619, they established a town that would serve as the Company's headquarter in Asia for the next three centuries. As part of the Company's security policy the Javanese people were made to feel unwelcome in Batavia, as the Dutch feared an uprising should they formed the majority of the city's population. To meet labor needs, Batavia instead imported large numbers of workers and slaves from other parts of the archipelago, such as the Maluku Islands and Bali. Notable among these attempts were Willem Ysbrandtszoon Bontekoe voyage to bring 1,000 Chinese immigrants to Batavia from Macao; however, only a small fraction of the 1,000 survived the trip. In 1621, another attempt was initiated and 15,000 people were deported from the Banda Islands to Batavia; on this occasion, only 600 survived the trip.

Having been established for almost a decade, Batavia, the first major Dutch settlement and trading post in Java, had naturally begun to draw hostility from the surrounding Javanese kingdoms. The European port and settlement was considered to be a foreign threat by the native polities. The sultans of Banten aspired to retake the port city and also to close down a major trading rival. However they could not afford to launch a campaign of a scale capable of retaking the port. Instead the Bantenese could only launch occasional small scale raids on Dutch interests outside of the city walls.

Meanwhile, in the east, Mas Jolang died in 1613 and was succeeded by his son Sultan Agung, who was to become the greatest of Mataram's rulers. Relationship with the Company became more tense, with Agung early in his reign (1614) specifically warning a Dutch embassy that peace with him would be impossible to maintain if they were to try to conquer any part of Java, over which he was determined to become sole ruler. In 1618 a misunderstanding resulted in the VOC's loji in Jepara being burnt by Agung's regent, with three VOC personnel being killed and the rest arrested; this in turn caused a reprisal by the Dutch fleet in the same year and the year after that destroyed most of the city. Nevertheless, relationship between the two parties remained mixed; like his father Agung desired the company's naval assistance against Surabaya and in 1621 he made overtures of peace, which the Company reciprocated with embassies in the three following years. The Dutch, however, declined his request for military support, as a result, diplomatic relations between the two sides were severed.

First siege (22 August–3 December 1628)

[edit]

Agung might have started his plans for the conquest of Batavia as early as 1626. Aside of his aversion of the Dutch, it was a natural stepping stone for the conquest of Banten, the last major independent Javanese state. As preparation for this he made an alliance with Cirebon although in practice she was treated as a vassal of Mataram. In April 1628 Kyai Rangga Tapa, the regent of Tegal was sent to Batavia to propose a peace treaty with certain conditions on Mataram's behalf. The Dutch however, declined this proposal as well. For Agung, this was the last straw and he put his plan of attacking Batavia into motion. He sent two forces, one by sea under Tumenggung (marquess) Bahureksa, the regent of Kendal, and another overland under Prince Mandudareja.

On August 25, 1628, the vanguard of Agung's navy arrived in Batavia. The Mataram naval armada brought extensive amount of supplies, including 150 cattle, 5,900 sacks of sugar, 26,600 coconuts and 12,000 sacks of rice. As a ruse de guerre they initially asked for permission to land in Batavia to trade, however the size of the Mataram fleet caused the Dutch to be suspicious. The next day the Dutch allowed the cattle to be delivered, with the condition that only one Mataram ship at a time may dock. One hundred armed guards watched the landing from Batavia Castle. On the third day three more Mataram ships arrived, claiming that they were there to ask for a travel permit to trade with Melaka. The Hoge Regering became increasingly alarmed at the sudden increase in Mataram ship arrivals, and moved more artillery pieces to Batavia Castle's two northern bastions. Finally in the afternoon twenty more Mataram ships arrived and began to openly unload their troops north of the castle, causing the alerted Dutch to pull all personnel back into the castle and open fire on the incoming Javanese. To deny shelter for the invading army, Coen had most of Batavia's bamboo shack suburbs burnt. On August 28, 1628, 27 more Mataram ships entered the bay but landed quite far from Batavia. On the south of Batavia the vanguard of the overland Mataram force began to arrive, with 1,000 men starting to apply pressure upon Batavia's southern flank. On August 29 the first of many Mataram attacks was launched against Fort Hollandia, located southeast of the city. One hundred twenty VOC troops under the command of Jacob van der Plaetten managed to repulse the attack and the Javanese suffered heavy losses. Several company ships also arrived from Banten and Onrust island, landing an additional 200 troops and increasing Batavia's garrison to 730 men.

The main part of the overland Mataram army arrived in October, bringing their total troop strength to 10,000 men. They blockaded all the roads running south and west of the city and tried to dam the Ciliwung river to limit the Dutch's water supply. This was of little use though, as repeated Mataram escalade attacks against the Dutch fortification resulted in nothing but heavy losses. Even worse, the Mataram commanders had not prepared for a long siege in an area devoid of local logistical support, and by December the army was already running out of supplies. Angered by the lack of success, on December 2 Sultan Agung sent his executioners to punish Tumenggung Bahureksa and Prince Mandurareja. The next day, the Dutch discovered that their opponent had marched home, leaving behind 744 headless corpses of their men.

Second Siege (May–September 1629)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

After the debacle of the first siege, Agung realized that the main hurdle to the conquest of Batavia was logistical, due to the immense distance (some 300 miles) his forces had to cross from their supply bases in Central Java.[2] He decided to establish numerous rice farming villages ran by Javanese farmers on the northern coast of Western Java, from Cirebon to Karawang.[2] This sparked the first wave of Javanese migrations to this previously sparsely populated area, resulting in the vast ricelands that characterized the area from Cirebon to Indramayu, Karawang, and Bekasi that still exist today.[2] By May 1629, Mataram was ready to launch its second attack on Batavia.[2]

The second invasion again consisted of two forces; the Sundanese army of Dipati Ukur, the regent of Priangan, a vassal of Mataram, and the main Javanese army led by Adipati Juminah, altogether some 20,000 strong. The original plan called for Ukur to wait for the main army to rendezvous with him in Priangan and to depart together in June, however lack of supplies forced Ukur to start his advance upon Batavia immediately. When Juminah arrived in Priangan, he was angered at the apparent insult Ukur had done to him. The angered Mataram officials and troops created havoc in Priangan, pillaging and raping local women. Hearing the news from his wife, the angered Ukur promptly withdrew from the campaign, going as far as killing a number of Mataram officials attached to his force. From the example of Tumenggung Bahureksa and Prince Mandurareja, Dipati Ukur knew that Sultan Agung would not tolerate failure, much less betrayal, and hence he decided to rise in rebellion against Mataram instead.

With lack of supplies and plagued with malaria and cholera that hit the region, the Mataram troops that arrived at Batavia were exhausted. Mataram troops established an encampment located south of Batavia in an area now known as Matraman (derived from "Mataraman"). The Mataram forces besieged Batavia and disrupted Batavia's water supply by polluting the Ciliwung River, causing a cholera plague in Batavia. During this second siege Jan Pieterszoon Coen suddenly died on 21 September 1629, most likely because of this cholera outbreak. With internal problems among their commanders, and plagued with illness and a lack of supply, Mataram forces were finally forced to retreat.

Aftermath

[edit]The Dipati Ukur withdrawal from the campaign and his rebellion weakened the Mataram hold on Priangan that created instability in West Java for several years. The Dutch however managed to firmly establish themselves in Java. The Batavia campaign failure had led Sultan Agung to shift his conquering ambitions to the east and attack Blitar, Panarukan and the Blambangan in Eastern Java, a vassal of the Balinese kingdom of Gelgel.

Because of Sultan Agung's harsh discipline against failure, large numbers of Javanese troops refused to return home to Mataram. Many of them decided to marry local women and settle down in northern West Java villages. This created the rice farming villages on the Pantura (pantai utara: north coast) region of West Java, spanning Bekasi, Karawang, Subang, Indramayu and Cirebon. The migration and settlement of the Javanese to Northern West Java created a distinctive culture, that later developed to be quite different from the highland Sundanese and Central Javanese counterparts.

In the following decades, the VOC successfully expanded their influence by acquiring Buitenzorg and the Priangan highlands, and also Mataram's north coast ports such as Tegal, Kendal and Semarang through concessions in Mataram's expense. This was possible primarily due to internal problems within the Mataram court, plagued with succession disputes and struggle for power. Some of the former Mataram encampments became place names in Jakarta today, and can be identified by their originally Javanese names, such as Matraman, Paseban and Kampung Jawa.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Coen, Jan Pieterszoon". Library Index. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Drs. R. Soekmono (1981). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 3, 2nd ed (in Indonesian) (1973, 5th reprint edition in 2003 ed.). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. p. 61. ISBN 9794132918.

References

[edit]- Romain Bertrand, L‘Histoire à parts égales. Récits d'une rencontre Orient-Occident (XVIe-XVIIe siècles), Paris, Seuil, 2011, chapter 15, pp. 420–436.