Skylab 4

The final view of Skylab, from the departing mission 4 crew | |

| Operator | NASA |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1973-090A |

| SATCAT no. | 6936 |

| Mission duration | 84 days, 1 hour, 15 minutes, 30 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 55,500,000 km (34,500,000 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 1214 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Apollo CSM-118 |

| Manufacturer | North American Rockwell |

| Launch mass | 20,847 kg (45,960 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| EVAs | 4 |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 16, 1973, 14:01:23 UTC |

| Rocket | Saturn IB SA-208 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS New Orleans |

| Landing date | February 8, 1974, 15:16:53 UTC |

| Landing site | 31°18′N 119°48′W / 31.300°N 119.800°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 422 km (262 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 437 km (272 mi) |

| Inclination | 50.04 degrees |

| Period | 93.11 minutes |

| Epoch | January 21, 1974[1] |

| Docking with Skylab | |

| Docking port | Forward |

| Docking date | November 16, 1973, 21:55:00 UTC |

| Undocking date | February 8, 1974, 02:33:12 UTC |

| Time docked | 83 days, 4 hours, 38 minutes, 12 seconds |

Due to a NASA management error, crewed Skylab mission patches were designed in conflict with the official mission numbering scheme.  Left to right: Carr, Gibson and Pogue Skylab program | |

Skylab 4 (also SL-4 and SLM-3[2]) was the third crewed Skylab mission and placed the third and final crew aboard the first American space station.

The mission began on November 16, 1973, with the launch of Gerald P. Carr, Edward Gibson, and William R. Pogue in an Apollo command and service module on a Saturn IB rocket from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida,[3] and lasted 84 days, one hour and 16 minutes. A total of 6,051 astronaut-utilization hours were tallied by the Skylab 4 astronauts performing scientific experiments in the areas of medical activities, solar observations, Earth resources, observation of the Comet Kohoutek and other experiments.

The crewed Skylab missions were officially designated Skylab 2, 3, and 4. Miscommunication about the numbering resulted in the mission emblems reading "Skylab I", "Skylab II", and "Skylab 3" respectively.[2][4]

Launch

[edit]

NASA's launch center was located in an area called Cape Kennedy since November 28, 1963.[5] Cape Kennedy was restored to its former name of Cape Canaveral officially on October 9, 1973.[6][7] The Saturn V launch facilities at LC-39A and LC-39B were still located at the Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island.[6] The Skylab 4 mission was the first crewed launch since the area changed its name back to Cape Canaveral;[8] it launched from the Kennedy Space Center's LC-39B pad on November 16, 1973.[9]

Crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Gerald P. Carr Only spaceflight | |

| Science Pilot | Edward G. Gibson Only spaceflight | |

| Pilot | William R. Pogue Only spaceflight | |

With three rookies, Skylab 4 was the largest all-rookie crew launched by NASA. Following the all rookie Mercury program, there were only four all-rookie NASA flights – Gemini 4, Gemini 7, Gemini 8, and Skylab 4.

Backup crew

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Vance D. Brand | |

| Science Pilot | William Lenoir | |

| Pilot | Don L. Lind | |

Support crew

[edit]- Robert L. Crippen

- Henry W. Hartsfield, Jr

- Bruce McCandless II

- F. Story Musgrave

- Russell L. Schweickart

- William E. Thornton

- Richard H. Truly

Mission parameters

[edit]| Mission |

|

|---|---|

| Skylab 2 | |

| Skylab 3 | |

| Skylab 4 |

- Mass: 20,847 kg (45,960 lb)

- Maximum altitude: 440 km (273 mi) (November 16, 1973)

- Total distance traveled: 34.5 million miles (55,500,000 km)

- Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB SA-208

- Spacecraft: Apollo CSM-118

- Epoch: January 21, 1974

- Perigee: 422 km (262 mi)

- Apogee: 437 km (272 mi)

- Inclination: 50.04°

- Period: 93.11 min

Docking

[edit]- Docked: November 16, 1973 – 21:55:00 UTC

- Undocked: February 8, 1974 – 02:33:12 UTC

- Time Docked: 83 days, 4 hours, 38 minutes, 12 seconds

Space walks

[edit]- Gibson and Pogue – EVA 1

- Start: November 22, 1973, 17:42 UTC

- End: November 23, 00:15 UTC

- Duration: 6 hours, 33 minutes

- Carr and Pogue – EVA 2

- Start: December 25, 1973, 16:00 UTC

- End: December 25, 23:01 UTC

- Duration: 7 hours, 01 minute

- Carr and Gibson – EVA 3

- Start: December 29, 1973, 17:00 UTC

- End: December 29, 20:29 UTC

- Duration: 3 hours, 29 minutes

- Carr and Gibson – EVA 4

- Start: February 3, 1974, 15:19 UTC

- End: February 3, 20:38 UTC

- Duration: 5 hours, 19 minutes

Mission highlights

[edit]

The all-rookie astronaut crew arrived aboard Skylab to find that they had company – three figures dressed in flight suits. Upon closer inspection, they found their companions were three dummies, complete with Skylab 4 mission emblems and name tags which had been left there by Al Bean, Jack Lousma, and Owen Garriott at the end of Skylab 3.[10]

Things got off to a bad start after the crew attempted to hide Pogue's early space sickness from flight surgeons, a fact discovered by mission controllers after downloading onboard voice recordings. Astronaut office chief Alan B. Shepard reprimanded them for this omission, saying they "had made a fairly serious error in judgement."[11]

The crew had problems adjusting to the same workload level as their predecessors when activating the workshop. The crew's initial task of unloading and stowing the thousands of items needed for their lengthy mission also proved to be overwhelming.[12] The schedule for the activation sequence dictated lengthy work periods with a large variety of tasks to be performed, and the crew soon found themselves tired and behind schedule.

Seven days into their mission, a problem developed in the Skylab gyroscopic attitude control system, which threatened to bring an early end to the mission. Skylab depended upon three large gyroscopes, sized so that any two of them could provide sufficient control and maneuver Skylab as desired. The third acted as a backup in the event of failure of one of the others.[13] The gyroscope failure was attributed to insufficient lubrication. Later in the mission, a second gyroscope showed similar problems,[14][15] but special temperature control and load reduction procedures kept the second one operating, and no further problems occurred.

On Thanksgiving Day, Gibson and Pogue accomplished a 61⁄2 hour spacewalk. The first part of their spacewalk was spent deploying experiments and replacing film in the solar observatory. The remainder of the time was used to repair a malfunctioning antenna. During the experience, Gibson remarked, "Boy if this isn't the great outdoors! Inside, you're just looking out through a window. Here, you're right in it."[16] The crew reported that the food was good, but slightly bland. The quantity and type of food consumed was rigidly controlled because of their strict diet. Although the crew would have preferred to use more condiments to enhance the taste of the food, and the amount of salt they could use was restricted for medical purposes, by the third mission the NASA kitchen had increased the availability of condiments, and salt and pepper was in liquid solutions (granular salt and pepper brought aboard by the second crew was little more than "air pollution").[17]

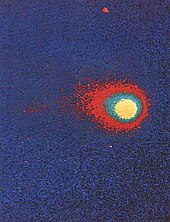

On December 13, the crew sighted Comet Kohoutek and trained the solar observatory and hand-held cameras on it. They gathered spectra on it using the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph.[18] They continued to photograph it as it approached the Sun. On December 30, as it swept out from behind the Sun, Carr and Gibson spotted it as they were performing a spacewalk.

As Skylab work progressed, the astronauts complained of being pushed too hard, and ground controllers complained they were not getting enough work done. NASA determined major contributing factors were a large number of new tasks added shortly before launch with little or no training, and searches for equipment out of place on the station.[19][20][21] There was a radio conference to air frustrations[22] which led to the workload schedule being modified, and by the end of their mission the crew had completed even more work than originally planned.

Skylab 4 was noted for several important scientific contributions. The crew spent many hours studying the Earth. Carr and Pogue alternately crewed controls, operating the sensing devices which measured and photographed selected features on the Earth's surface. Gibson and the other crew made solar observations, recording about 75,000 new telescopic images of the Sun. Images were taken in the X-ray, ultraviolet, and visible portions of the spectrum.[19][23]

As the end of their mission drew closer, Gibson continued his watch of the solar surface. On January 21, 1974, an active region on the Sun's surface formed a bright spot which intensified and grew.[19] Gibson quickly began filming the sequence as the bright spot erupted. This film was the first recording from space of the birth of a solar flare.

The crew also photographed the Earth from orbit. Despite instructions not to do so, the crew (perhaps inadvertently) photographed Area 51, causing a minor dispute between various government agencies as to whether the photographs showing this secret facility should be released. In the end, the picture was published along with all others in NASA's Skylab image archive, but remained unnoticed for years.[24]

The Skylab 4 astronauts completed 1,214 Earth orbits and four EVAs totaling 22 hours, 13 minutes. They traveled 34.5 million miles (55,500,000 km) in 84 days, 1 hour and 16 minutes in space. Skylab 4 was the last Skylab mission; the station fell from orbit in 1979.

The three astronauts had joined NASA in the mid-1960s, during the Apollo program, with Pogue and Carr becoming part of the likely crew for the cancelled Apollo 19. Ultimately none of the crew of Skylab 4 flew in space again, as none of the three had been selected for Apollo–Soyuz and all of them retired from NASA before the first Space Shuttle launch. Gibson, who had trained as a scientist-astronaut, resigned from NASA in December 1974 to do research on Skylab solar physics data, as a senior staff scientist with The Aerospace Corporation of Los Angeles, California.

Communications break

[edit]An unplanned communications break occurred during the Skylab 4 mission: its crew did not communicate with mission control for the portion of one orbit during which Skylab had line of sight to its tracking stations.[25] Before the midpoint of the mission, the Skylab 4 crew had started to become fatigued and behind on the work. In order to catch up, they decided that only one crew member needed to be present for the daily briefing instead of all three, allowing the other two to complete ongoing tasks.[26] At one point, according to both Carr and Gibson, the crew forgot to turn their radios on for the daily briefing, leading to a lack of communications between the crew and ground control during that orbit's period of communications availability. By the next planned period, the crew had reaffirmed radio contact with ground control.[26][27] Both Carr and Gibson stated that this event partially contributed to a discussion on December 30, 1973, in which the crew and ground control capsule communicator Richard H. Truly revisited the astronauts' schedule in light of their fatigue. Carr called this meeting "the first sensitivity session in space".[26][27] NASA agreed to assign the crew a more relaxed schedule, and productivity for the remaining mission significantly increased, surpassing that of the prior Skylab 3 mission.[28]

Consequences

[edit]

While the lack of communications was unintentional, NASA still spent time to study its causes and effects as to avoid its replication in future missions.[30]

At the time, only the crew of Skylab 3 had spent six weeks in space. It was unknown what had happened psychologically. NASA carefully worked with crew's requests, reducing their workload for the next six weeks. The incident took NASA into an unknown realm of concern in the selection of astronauts, still a question as humanity considers human missions to Mars or returning to the Moon.[31] Among the complicating factors was the interplay between management and subordinates (see also Apollo 1 fire and Challenger disaster). On Skylab 4, one problem was that the crew was pushed even harder as they fell behind on their workload, creating an increasing level of stress.[32] Even though none of the astronauts returned to space, there was only one more NASA spaceflight in the decade and Skylab was the first and last American space station.[33] NASA was planning larger space stations but its budget shrank considerably after the Moon landings, and the Skylab orbital workshop was the only major execution of Apollo Applications projects.[33]

Though the final Skylab mission became known for the incident, it was also known for the large amount of work that was accomplished in the long mission.[34] Skylab orbited for six more years before its orbit finally decayed in 1979 due to solar activity that was higher than expected.[30] The next U.S. spaceflight was the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project conducted in July 1975, and after a human spaceflight gap, the first Space Shuttle orbital flight STS-1 in April 1981.

The event, which the involved astronauts have joked about,[35] has been extensively studied as a case study in various fields of endeavor including space medicine, team management, and psychology. Man-hours in space were, and continued to be into the 21st century, an expensive undertaking; a single day on Skylab was worth about $22.4 million in 2017 dollars, and thus any work stoppage was considered inappropriate due to the expense.[36] According to Space Safety Magazine, the incident affected the planning of future space missions, especially long-term missions.[34]

The described events were considered a significant example of "us versus them" syndrome in space medicine.[37] Crew psychology has been a point of study for Mars analog missions such as Mars-500, with a particular focus on crew behavior triggering a mission failure or other issues.[37] One of the impacts of the incident is the requirement that at least one member of the International Space Station crew be a space veteran (not be on a first flight).[38]

The 84-day stay of the Skylab 4 mission was a human spaceflight record that was not exceeded for over two decades by a NASA astronaut.[39] The 96-day Soviet Salyut 6 EO-1 mission broke Skylab 4's record in 1978.[40][41]

The strike or mutiny myth

[edit]The communications failure was treated by the media as a deliberate act and became known as the Skylab strike or Skylab mutiny. One of the first accounts reporting that a strike aboard Skylab had occurred was published in The New Yorker on August 22, 1976, by Henry S. F. Cooper, who claimed that the crew were alleged to have stopped working on December 28, 1973.[42][28] Cooper also published similar claims in his book A House in Space that same year.[28] The Harvard Business School published a 1980 report, "Strike in Space", also claiming that the astronauts had gone on strike, but without citing any sources.[28] Subsequently, enough media gave weight to the popular notion that there was a Skylab strike on December 28, 1973, to ensure the narrative was established.[28]

NASA, the astronauts involved, and spaceflight historians have confirmed that no strike occurred. NASA has suggested the events of December 28 may have been confused with a day off that was given to the crew on December 26 following the completion of a long spacewalk by Carr and Pogue the day before.[26][28] NASA added that there may also have been confusion with a known ground equipment failure on December 25; this left them unable to track Skylab for one orbit, but the crew were notified of this issue ahead of time.[28] Both Carr and Gibson have affirmed that it was a series of misjudgments and not the crew's intent that caused them to miss the briefing.[26][27][43] Spaceflight history author David Hitt also disputed that the crew deliberately ended contact with mission control, in a book written with former astronauts Owen K. Garriott and Joseph P. Kerwin.[44]

Despite these reports, the notion of a deliberate action persists in the media.[28][35][45]

Gallery

[edit]-

Commander Gerald Carr flies a Manned Maneuvering Unit prototype.

-

Carr "balances" Bill Pogue as a demonstration of zero-G.

-

Ed Gibson floats out of the Multiple Docking Adapter connecting the station to the crew's Command Module.

-

Carr and Gibson look through the length of the station from the trash airlock.

-

Carr floats with limbs outstretched to show the effects of zero-G.

-

The Pogue Seiko, a 'Seiko Automatic-Chronograph' Cal. 6139, the first automatic chronograph in space, used by Bill Pogue[46][47]

-

Gibson at the controls of the Apollo Telescope Mount

-

Dr. Lubos Kohoutek, discoverer of the Comet Kohoutek, speaks to the Skylab 4 crew via radio-telephone in the Mission Operations Control Room in the Mission Control Center during a visit to JSC.

-

Gibson during an EVA

Command Module legacy

[edit]

The Skylab 4 command module was transferred to the National Air and Space Museum in 1975.[48] This module is the Command and Service Modules CSM-118 and it spent 84 days in Earth orbit as part of the Skylab mission.[49] As of September 2020 it is on display at the Oklahoma History Center.[49]

The module rolled upside down after splashdown, which happened in about half the Apollo CSM splashdowns; in this situation spheres were inflated on top of the CSM to right the module.[50]

The windows of the Skylab 3 and 4 spacecraft modules were studied for micrometeoroid impacts.[51]

The module was painted white on half its side to help with spacecraft thermal management.[52] Whereas Block II Apollo CSM had Kapton coated with aluminium and silicon monoxide, later Skylab modules had white paint for the sunward side.[52]

The Skylab 4 Command Module held the record for the longest single spaceflight for an American spacecraft for nearly 50 years until it was broken by Crew Dragon Resilience flying the SpaceX Crew-1 mission on February 7, 2021. To commemorate the event, the four person crew of Crew-1 spoke live with Edward Gibson from the International Space Station.[53]

The capsule is now on display at the Oklahoma History Center in Oklahoma City.[54]

Mission insignia

[edit]The triangular emblem features a large number 3 and a rainbow circling three areas of study the astronauts pursued. At the time of the flight, the astronauts issued the following description:

"The symbols in the patch refer to the three major areas of investigation in the mission. The tree represents man's natural environment and refers to the objective of advancing the study of earth resources. The hydrogen atom, as the basic building block of the universe, represents man's exploration of the physical world, his application of knowledge, and his development of technology. Since the sun is composed primarily of hydrogen, the hydrogen symbol also refers to the Solar Physics mission objectives. The human silhouette represents mankind and the human capacity to direct technology with a wisdom tempered by his regard for his natural environment. It also relates to the Skylab medical studies of man himself. The rainbow, adopted from the Biblical story of the Flood, symbolizes the promise that is offered to man. It embraces man and extends to the tree and hydrogen atom, emphasizing man's pivotal role in the conciliation of technology with nature by a humanistic application of our scientific knowledge."

Some versions of the patch included a comet in the top curve because of studies made of the comet Kohoutek.

See also

[edit]- Extra-vehicular activity

- List of spacewalks

- Splashdown (spacecraft landing)

- Timeline of longest spaceflights

- Psychological and sociological effects of spaceflight

- Team composition and cohesion in spaceflight missions

- Effects of sleep deprivation in space

References

[edit]- ^ McDowell, Jonathan. "SATCAT". Jonathan's Space Pages. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ a b "Skylab Numbering Fiasco". Living in Space. William Pogue Official WebSite. 2007. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ "'Three happy rookies' off on longest space voyage". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. November 16, 1973. p. 1A.

- ^ Pogue, William. "Naming Spacecraft: Confusion Reigns". collectSPACE. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ "It's Cape Kennedy now". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. (Florida). Associated Press. November 29, 1963. p. 1.

- ^ a b Lethbridge, Clifford J. Spaceline.org "Cape History". Spaceline.org. Retrieved on March 23, 2011.

- ^ "Cape Kennedy is now Cape Canaveral". Lakeland Ledger. (Florida). (Washington Post). October 10, 1973. p. 8A.

- ^ "Skylab astronauts set for 9:01 launch today". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. (Florida). November 16, 1973. p. 1A.

- ^ "Third Skylab crew fired aloft". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. November 16, 1973. p. 1.

- ^ "Photo-sl3-113-1587". spaceflight.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (November 18, 1973). "Skylab Astronauts Are Reprimanded In 1st Day Aboard". The New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Astronauts Try to Make Up Time". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 19, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "A Skylab Gyroscope Fails, Leaving Only 2 for Control". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 24, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Gyro on Skylab Is Erratic; Officials Are Not Alarmed". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 8, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Skylab Gyroscope Falters, Puzzling Ground Engineers". The New York Times. United Press International. January 4, 1974. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Two Astronauts fix Skylab Antenna". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 23, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Erling, John (2013) Interview with William Pogue Archived May 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Voices of Oklahoma. p. 33.

- ^ Lundquist, C. A. (January 1979). "SP-404 Skylab's Astronomy and Space Sciences". Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c Canby, Thomas (October 1974). "Skylab, Outpost on the Frontier of Space". National Geographic Magazine. 146: 441–493.: 468

- ^ "Lethargy of Skylab 3 Crew Is Studied". The New York Times. Reuters. December 12, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Skylab Crew Takes Day Off for Rest". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 25, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Astronauts Debate Work Schedules With Controllers". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 31, 1973. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ Edward G. Gibson Biographical Data. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

- ^ Secret Apollo. The Space Review. November 26, 2007

- ^ Broad, William J. (July 16, 1997). "On Edge in Outer Space? It Has Happened Before". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Brewer, Kirstie (March 20, 2021). "Skylab: The myth of the mutiny in space". BBC. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rusnak, Kevin (October 25, 2000). Oral History Transcript - Gerald Carr (PDF) (Report). NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Uri, John (November 16, 2020). "The Real Story of the Skylab 4 "Strike" in Space". NASA. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Van Dongen, HP; Maislin, G; Mullington, JM; Dinges, DF (2003). "The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: Dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation". Sleep. 26 (2): 117–26. doi:10.1093/sleep/26.2.117. PMID 12683469.

- ^ a b "Skylab: First U.S. Space Station". Space.com. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ DNews (April 16, 2012). "Why 'Space Madness' Fears Haunted NASA's Past". Seeker – Science. World. Exploration. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "Skylab: America's First Home in Space Launched 40 Years Ago Today". WIRED. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "Skylab: Everything You Need to Know". www.armaghplanet.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "All the King's Horses: The Final Mission to Skylab (Part 3)". Space Safety Magazine. December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b Vitello, Paul (March 10, 2014). "William Pogue, Astronaut Who Staged a Strike in Space, Dies at 84". The New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Lafleur, Claude (March 8, 2010). "Costs of US Piloted Programs". The Space Review. Retrieved February 18, 2012. See author's correction in comments section.

- ^ a b Clément, Gilles (July 15, 2011). Fundamentals of Space Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-9905-4.

- ^ Gilles Clément (2011). Fundamentals of Space Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-4419-9905-4.

- ^ Harding, Kiesha (2006). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Duration of the longest space flight". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Pike, John. "Soyuz 26 and Soyuz 27". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ Hollingham, Richard (December 21, 2015). "How the most expensive structure in the world was built". BBC.

- ^ Cooper, Henry S. F. (August 30, 1976). "Life in a Space Station". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Butler, Carol (December 1, 2000). "Oral History Transcript - Edward G. Gibson". NASA Johnson Space Center. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Hitt, David (2008). Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803219014. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael. "The day when three NASA astronauts staged a strike in space". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ William Pogue's Seiko 6139 Watch Flown on Board the Skylab 4 Mission, from his Personal Collection... The First Automatic Chronograph to be Worn in Space. Heritage Auctions

- ^ The "Colonel Pogue" Seiko 6139. dreamchrono.com.

- ^ Skylab 4 Command Module Archived May 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved on August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b "Command Module, Skylab 4". collectSPACE. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Upside-Down Astronauts". NASA. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Cour-Palais, B. G. (March 1979). Results of the examination of the Skylab/Apollo windows for micrometeoroid impacts. 10th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Vol. 2. Houston, Texas. p. 1665. Bibcode:1979LPSC...10.1665C.

- ^ a b "Making The Command Module's Heat Shield". Spaceflight Blunders & Greatness. March 4, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ "US crewed spacecraft flight duration record - collectSPACE: Messages".

- ^ "Skylab 4 capsule to land in new exhibit at Oklahoma History Center -collectSPACE".

Further reading

[edit]- Gilles Clement, Fundamentals of Space Medicine, Microcosm Press, 2003. pp. 212.

- Lattimer, Dick (1985). All We Did was Fly to the Moon. Whispering Eagle Press. ISBN 0-9611228-0-3.

External links

[edit]- Skylab: Command service module systems handbook, CSM 116 – 119 (PDF) April 1972

- Skylab Saturn 1B flight manual (PDF) September 1972

- NASA Skylab Chronology

- Marshall Space Flight Center Skylab Summary

- Skylab 4 Characteristics SP-4012 NASA HISTORICAL DATA BOOK

- Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident

- Skylab, "The Third Manned Period", NASA History (History.nasa.gov )

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with William Pogue. First person interview conducted with William Pogue on August 8, 2012. Original audio and transcript archived with Voices of Oklahoma oral history project.

![The Pogue Seiko, a 'Seiko Automatic-Chronograph' Cal. 6139, the first automatic chronograph in space, used by Bill Pogue[46][47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Seiko_Automatic-Chronograph_Cal._6139_mit_gelbem_Zifferblatt%2C_die_sogenannte_%E2%80%9EPogue_Seiko%E2%80%9C.jpg/101px-Seiko_Automatic-Chronograph_Cal._6139_mit_gelbem_Zifferblatt%2C_die_sogenannte_%E2%80%9EPogue_Seiko%E2%80%9C.jpg)