Tazabagyab culture

| |

| Geographical range | Lower Amu Darya |

|---|---|

| Period | Late Bronze Age |

| Dates | ca. 1850–1500 BC |

| Preceded by | Kelteminar culture Andronovo culture Suyarganovo culture (in lower Amu Darya river) Zamanbaba culture (in lower Zeravshan river) |

| Followed by | Amirabad culture Begazy–Dandybai culture (in lower Amu Darya river) |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

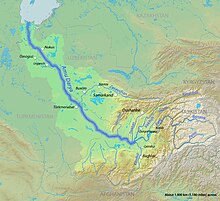

The Tazabagyab culture is from the late Bronze Age, ca. 1850 BC to 1500 BC,[1] and flourished in the lower Zeravshan valley, as well as along the lower Amu Darya towards the south shore of the Aral Sea; this last region is known as Khwarazm or Khorezm. Earlier it was thought to be from ca. 1500 BC to 1100 BC and regarded a southern offshoot of the Andronovo culture, composed of Indo-Iranians,[2] but Stanislav Grigoriev, in a recent study asserts that Tazabagyab is not part of the Andronovo cultural horizon.[3]

Origins

[edit]The Tazabagyab culture emerged in the lower Zeravshan valley and lower Amu Darya around 1850 BC,[1] earlier thought to be a southern variant of the Andronovo culture,[4][5][6] but now considered an independent culture.[3] Unlike the Andronovo peoples further to the north, who were largely pastoral, the people of the Tazabagyab culture were largely agricultural.[2]

Mallory/Adams (1997) described that they were descended from Indo-Iranian steppe herders from the north, who would have spread southwards and established agricultural communities.[2]

Tazabagyab culture's sites located in the Amu Darya delta formed a border zone, between Andronovo and Srubnaya steppe cultures in the north, and southern oasis cultures of Central Asia, during the Late Bronze Age. The burial site in Kokcha 3, located near Sultanuizdag mountain, around 250 km to the south of Aral Sea, is the largest cemetery excavated until now.[7]

Characteristics

[edit]

Tazabagyab settlements show evidence of small-scale irrigation agriculture.[5] About fifty settlements have been discovered.[8] These contained subterranean rectangular houses, usually three per village.[8] Tazabagyav houses are generally large, some being more than 10 x 10 m in dimensions. They are built of clay and the reeds are supported by timber posts. Ca. 100 individuals, belonging to around ten families,[5] would have inhabited a Tazabagyav village. Figurines and remains of horses have been found.[2]

In Tazabagyav burials, males are buried on their left, while females are buried on their right. This is similar to contemporary Indo-European cultures in the region, such as the Andronovo culture,[5] Bishkent culture, the Swat culture and the Vakhsh culture,[2] and the earlier Corded Ware culture of central and eastern Europe.[9][10][11] This practice has been identified as a typical Indo-Iranian tradition.[12]

Metal objects of the Tazabagyab culture are similar to those of the Andronovo culture in Kazakhstan, and of the Srubnaya culture further west.[2] Archaeological evidence show that Tazabagyab settlements included metal-working craftsmen.[8]

Its ceramics were of the Namazga VI type which was common throughout Central Asia at the time.[2] Tazabagyav pottery appears throughout a wide area.[6]

The Tazabagyab people appears to have controlled the trade in minerals such as copper, tin and turquoise, and pastoral products such as horses, dairy and leather. This must have given them great political power in the old oasis towns of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex. Their mastery of chariot warfare must have given them military control. This probably encouraged social, political and also military integration.[13]

Successors

[edit]David W. Anthony suggests that Tazabagyav culture might have been a predecessor of early Indo-Aryan peoples such as the compilers of the Rigveda and the Mitanni.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Garner, Jennifer, (2020). "Metal sources (tin and copper) and the BMAC", in The World of the Oxus Civilization, Chapter 28, Routledge, Table 28.1: "Andronovo-Tazabag'jab, 1850-1500 BC (after Parzinger and Boroffka 2003: 280, fig. 1)"

- ^ a b c d e f g Mallory & Adams 1997, pp. 566–567.

- ^ a b Grigoriev, Stanislav, (2021). "Andronovo Problem: Studies of Cultural Genesis in the Eurasian Bronze Age", in Open Archaeology 2021 (7), p.5: "...In western literature, for example, the Tazabagyab culture of the southern Aral Sea region is sometimes viewed as a variant of the Andronovo culture (Mallory & Adams, 1997, p. 566). But experts on the Andronovo culture do not consider Tazabagyab as Andronovo..." .

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Mallory 1991, p. 230.

- ^ a b Anthony 2010, p. 452.

- ^ Schreiber, Finn, (2022). "Social and chronological aspects of the Late Bronze age burial site of Kokcha 3 (Uzbekistan)", in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 44, Abstract: "The Amu-Darya Delta (ancient Khwarazm, modern Uzbekistan) was a borderland between northern steppe-based Andronovo-Srubnaya groups and southern oasis cultures in the Late Bronze Age. The local sites are known as the Tazabag'yab culture, of which Kokcha 3 is the largest excavated burial site."

- ^ a b c Masson 1992, p. 350.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 68.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 589.

- ^ Mallory 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 1997, p. 558.

- ^ a b Anthony 2010, pp. 453–454.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anthony, David W. (2010) [2007]. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3110-4.

- Mallory, J. P. (1991). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). "Tazabagyab Culture". Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 566–567. ISBN 1884964982.

- Masson, V. M. [in French] (1992). "The Decline of the Bronze Age Civilization and Movements of the Tribes". In Dani, A. H.; Masson, V. M. [in French] (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Dawn of Civilization. Vol. 1. UNESCO. pp. 337–431. ISBN 9231027190.

Further reading

[edit]- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.