The Addiction

| The Addiction | |

|---|---|

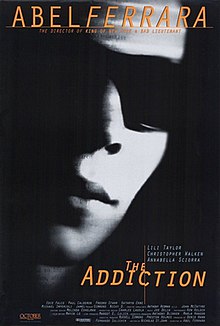

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Abel Ferrara |

| Written by | Nicholas St. John |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ken Kelsch |

| Edited by | Mayin Lo |

| Music by | Joe Delia |

| Distributed by | October Films |

Release dates | |

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $302,393 |

The Addiction is a 1995 American vampire horror film directed by Abel Ferrara and written by Nicholas St. John. Starring Lili Taylor, Christopher Walken, Annabella Sciorra, Edie Falco, Paul Calderón, Fredro Starr, Kathryn Erbe, and Michael Imperioli, the film follows a philosophy graduate student who is turned into a vampire after being bitten by a woman during a chance encounter on the streets of New York City. After the attack, she struggles coming to terms with her new lifestyle and begins developing an addiction for human blood. The film was shot in black-and-white and has been considered an allegory about drug addiction and the theological concept of sin.[1][2]

The Addiction premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on January 21, 1995, and was screened at the 45th Berlin International Film Festival on February 18, 1995, where it was nominated for the Golden Bear.[3] The film was theatrically released in the United States on October 6, 1995. Despite underperforming commercially, the film received positive reviews, with Taylor's performance earning critical praise. At the 11th Independent Spirit Awards, Ferrara was nominated for Best Feature and Taylor was nominated for Best Female Lead.[4][5]

Film critic Peter Bradshaw named The Addiction as one of his top ten favourite films in a 2002 Sight and Sound poll.[6]

Plot

[edit]Kathleen Conklin, an introverted graduate student of philosophy at New York University, is attacked one night by a woman who calls herself "Casanova". She pushes Kathleen into a stairwell, bites her neck and drinks her blood. Kathleen soon develops several traditional symptoms of vampirism such as aversion to daylight and distaste for food. She grows aggressive in demeanor and propositions her dissertation advisor for sex at her apartment, stealing money from his wallet after he falls asleep. Jean, a doctoral candidate in Kathleen's cohort, notices a drastic change in Kathleen's personality.

During finals week in the library, Kathleen meets a female anthropology student. They go to the woman's apartment to study, where Kathleen bites her neck. While the young woman weeps incredulously, Kathleen coldly informs her "My indifference is not the concern here, it's your astonishment that needs studying". Later, Kathleen runs into an acquaintance, who goes by the street name "Black", at a deli. She propositions him for sex and the two leave, but soon attacks him on an empty street and drinks his blood. Later on campus, Kathleen confronts Jean, rambling about the nature of guilt, before proceeding to bite her neck and drink her blood.

While walking on the street, Kathleen meets Peina, a vampire who claims to have almost conquered his addiction and as a result is almost human. For a time, he keeps her in his home, trying to help her overcome hers, recommending that she read William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch. Later, Kathleen defends her dissertation to a committee and is awarded her Doctorate of Philosophy. At the graduation party, she and Jean feast on the blood of a waitress in a storage closet. Afterwards, she, Jean, Casanova, and the other victims proceed to attack the other attendees in a bloody, chaotic orgy.

Kathleen, having overdosed from the bloody bacchanal and appearing wracked with regret, wanders the streets covered in blood. She ends up in a hospital and asks the nurse to let her die but the nurse refuses. Kathleen decides to commit suicide by asking the nurse to open the curtains. After the nurse leaves, Casanova appears in Kathleen's hospital room, shuts the curtains and quotes R. C. Sproul to her. Next, a Catholic priest visits Kathleen's room and agrees to administer Viaticum. In the final scene, Kathleen visits her own grave in broad daylight. In a voice-over, Kathleen quotes: "self-revelation is annihilation of self".

Cast

[edit]- Lili Taylor as Kathleen Conklin

- Christopher Walken as Peina

- Annabella Sciorra as Casanova

- Edie Falco as Jean

- Paul Calderon as Professor

- Fredro Starr as Black

- Kathryn Erbe as Anthropology Student

- Michael Imperioli as Missionary

- Jamel Simmons as Black's Friend

- Robert W. Castle as Narrator / Priest

Production

[edit]Concept

[edit]According to Abel Ferrara, the characters of Peina and Casanova were originally written as a female and male respectively. When Walken read the script, he thought Peina was a male character and wanted to play the role. As a result, Walken had his way on portraying Peina whereas Casanova was played by Sciorra.[7] Ferrara said in a 2018 interview that he intended the film to be an explicit metaphor for drug addiction; Ferrara had lived with a years-long addiction to heroin, and conceptualized the film as a Catholic redemption tale in which Kathleen, stricken by her lust for blood, accepts her powerlessness and submits to God before being reborn in the conclusion.[8]

Filming

[edit]The Addiction was shot on location in Manhattan, in Greenwich Village and on the New York University campus.[8] The sequences inside Peina's home were shot in a loft owned by Julian Schnabel, who allowed Ferrara to film there.[8] Lili Taylor recalled meeting with Ferrara and rehearsing scenes at his apartment during evenings leading up to the shoot.[8] Taylor and co-star Michael Imperioli, whom she was dating at the time, would walk the streets in Manhattan late at night, which Taylor stated helped her get into the mindset of the character.[8]

Analysis

[edit]Scholar David Carter interprets The Addiction as a reimagining of the vampire film, in which the vampire's victims submit to being bitten and thus take on bloodlust for themselves

Historically within fiction, while vampires so often represent sexual desire, the baggage that came with that desire was being a slave to it. Vampires need and lust for blood at base primal level. Within The Addiction it's taken even further. Vampires are themselves the addicted and the addiction, foisting themselves alluringly upon people who want to dabble in something dangerous and all consuming. The words Casanova speaks to Kathleen (“Look at me and tell me to go away. Don't ask, tell me”) become a refrain in the film, the idea being that the prey want to become addicted even when they know the risks.[9]

Scholar Tom Pollard interprets the film as a metaphor for drug addiction, which Ferrara has called as the theme of the film.[8] "This plot relies on human willpower to control addiction... Eventually [Kathleen] achieves the necessary willpower and seemingly triumphs over death after she's reborn as a human".[1] In addition to the thematic parallel to drug addiction noted by several critics and scholars, Slant Magazine's Ed Gonzalez considers the film "perhaps the most fabulously serpentine political work of Ferrara's career, a quivering nexus of AIDS allegory, identity crisis, historical unease, and socio-economic panic".[10] Film scholars Yoram Allon, Del Cullen and Hannah Patterson note the film's preoccupation with religion, salvation and self-destruction, which are recurrent in Ferrara's films and add that it "perfectly illustrates Ferrara's obsession with the collapse of moral order".[11]

Film critic Stephen Hunter interprets the film as a commentary on the world of academe, pointing out Kathleen's transformative disillusion with philosophy as a means of understanding the nature of good versus evil, "She's got a grudge against philosophy, which, in the long run, with all its constructs and rationalizations and insights, has proved somewhat inefficient as salvation".[12]

Release

[edit]The Addiction premiered in New York City on October 4, 1995, and opened in Los Angeles two days later, on October 6, 1995.[13] It was distributed in North American markets by October Films, who one month earlier released Nadja, a vampire film also shot in black-and-white and set in New York City.[14]

Home media

[edit]The Addiction remained unreleased on DVD in North America throughout the 2000s, though a VHS was released in 1998 by USA Films.[15] In March 2018, Arrow Films announced an upcoming Blu-ray release of the film available in North America and the United Kingdom,[16] which was released on June 26, 2018.[17] The Arrow Blu-ray features a new 4K restoration of the film, and contains contemporary interviews with Taylor, Walken, Ferrara, and composer Joe Delia, as well as an audio commentary with Ferrara, among other features.[17] As of November 29, 2023,[update] the film has been available as part of the Criterion Channel's 90's Horror collection.[18]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Addiction grossed a total of $46,448 during its opening weekend, playing in seven cinemas in the United States, averaging $6,635 per theater.[19] It expanded to a total of 14 theaters before closing on January 11, 1996, concluding its theatrical run with a domestic gross of $307,308.[19]

Critical response

[edit]As of January 2, 2022[update], the film holds a rating of 74% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 31 reviews, with an average rating of 6.4/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Abel Ferrara's 1995 horror/suspense experiment blends urban vampire adventure with philosophical analysis to create a smart, idiosyncratic and undeniably odd take on the genre."[20]

Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times praised Taylor's performance, and added: "Although Ferrara dares to be intellectual in a manner virtually unique in commercial American cinema, he nevertheless doesn't forget how to entertain in the gory, bravura manner associated with him. Although it undeniably helps, you don't have to know your Heidegger from Hamburger Helper to enjoy The Addiction as a grisly yet unusual thriller of the supernatural."[21] The Washington Post's Hal Hinson was less laudatory of Taylor's performance, writing that she "seems less distinctive here than she has been in past roles." However, he praised Walken's performance, though summarized the film as "serious and passionate; [Ferrara's] conviction, too, is unquestionable. However, when he flashes images of historic atrocities of both the distant and recent past—Nazi death camps, the war dead in Bosnia—his ideas come across as shallow and banal. Also, inserting scenes of real-life horror into what is essentially a glorified genre exercise may strike some as the essence of bad taste."[22] Caryn James of The New York Times expressed a similar sentiment, noting "When the film connects Kathleen's struggle to resist evil to My Lai and the Holocaust, those comparisons are exploitative in a way that even a genre-bending film can't get away with."[23]

Stephen Hunter of The Baltimore Sun praised Taylor for portraying Kathleen "with dour, sexless intensity," and deemed the film "far sexier than Interview with the Vampire and far deadlier than the campy Nadja... It's extremely disturbing, a graduate- level movie for advanced students in any of three subjects: cinema, philosophy and debauchery."[12]

Accolades

[edit]At the 45th Berlin International Film Festival, the film was nominated for the Golden Bear award.[3] Lili Taylor won the Sant Jordi Award for Best Foreign Actress. The film received Best Actress (Taylor), Best Film (Abel Ferrara) and Special Mention Award (Walken) at the Málaga International Week of Fantastic Cinema.

At the 11th Independent Spirit Awards, the film was nominated for Best Feature and Best Female Lead.[4] At Mystfest, it won the Critics Award and was also nominated for Best Film.[5] The film received high praise from critic Peter Bradshaw, who named it as one of his top ten favourite films in a 2002 Sight and Sound poll.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Pollard 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Sánchez, Rodríguez; Antonio, Juan (2011). "Vampirism as a Metaphor for Addiction in the Cinema of the Eighties (1987–1995)". Journal of Medicine and Movies. 7 (2). Universidad de Salamanca Press: 69–79.

- ^ a b "Programme 1995". Berlin International Film Festival. Archived from the original on May 8, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Dretzka, Gary (January 12, 1996). "Film Nominations are Independent-minded". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Addiction Blu Ray Review (Arrow Video)". Today's Haul. August 6, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Addiction (1994)". BFI. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Vestby, Ethan (December 9, 2013). "Abel Ferrara On Artistic Freedom, Collaboration". The Film Stage. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor, Lili; Walken, Christopher; Delia, Joe (2018). "Talking with the Vampires" (Blu-ray documentary featurette). Arrow Films. OCLC 1042246150.

- ^ Carter, David (November 2, 2017). "Born Again Vampires: Abel Ferrara's The Addiction". Indiana University Cinema. Indiana University. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ed (May 27, 2006). "Blog-a-Thon: Abel Ferrara's The Addiction". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ Allon, Cullen & Patterson 2000, pp. 163–164.

- ^ a b "Facing the evil vampire Movie review: Abel Ferrara's "The Addiction" is on the surface about vampires, but it's really an examination of evil". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. November 10, 1995. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ "The Addiction". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ Koehler, Robert (September 24, 1995). "Dueling Vampires Stake Out Territory". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ Addiction, The [VHS]. ASIN 630403220X.

- ^ @ArrowFilmsVideo (March 29, 2018). "New UK/US/CA Title: The Addiction (Blu-ray)" (Tweet). Archived from the original on January 21, 2019 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Gingold, Michael (March 29, 2018). "Satisfy "The Addiction" with Arrow's Blu-ray of Abel Ferrara's Cult Favorite; Info and Art". Rue Morgue. ISSN 1481-1103. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ "The Addiction - '90s Horror". The Criterion Channel. Retrieved 2023-11-28.

- ^ a b "The Addiction (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Addiction (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (October 6, 1995). "MOVIE REVIEW : 'Addiction': Gore in an Intellectual Vein". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (October 27, 1995). "The Addiction". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019.

- ^ James, Caryn (October 4, 1995). "FILM REVIEW;A Philosophy Student Who Bites". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Addiction (1994)". BFI. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Allon, Yoram; Cullen, Del; Patterson, Hannah, eds. (2000). The Wallflower Critical Guide to Contemporary North American Directors. London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-903-36410-9.

- Pollard, Tom (2016). Loving Vampires: Our Undead Obsession. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-49778-2.

External links

[edit]- 1995 films

- 1995 horror films

- 1995 independent films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s supernatural horror films

- American black-and-white films

- American supernatural horror films

- American vampire films

- Films about academia

- Films directed by Abel Ferrara

- Films scored by Joe Delia

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New York City

- 1990s American films

- English-language horror films

- English-language independent films